What can the archives of diaspora communities look like, and how might we go about building them? These are practical questions that I have recently grappled with as a British-born Iranian in the diaspora, stemming from curiosities that have arisen through my

work researching the history of Iran and Iranians. To be part of a diaspora is to experience a dislocation, to be a scattered part of a larger, fractured whole. People in diasporic communities hold memories, stories, and embodied histories, and often physical items, letters, photographs, and other belongings that carry

traces of familiar pasts. In the Prison Notebooks, Antonio Gramsci wrote:

Marral Shamshiri

An Archive of

Exile and Diaspora:

The Iranian-American

Digital Archive Project

“The starting-point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical process to date which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory”.

To me, the process of compiling an inventory, or archive, for a diaspora, bound to the ‘infinity of traces’ that Gramsci famously wrote about, feels like a deeply human need to collectively build

and share a critical awareness about the complex histories of a particular community. It involves recognition of how migration, exile, revolution, labour, and war, are some of the large scale historical realities common to the Iranian experience that have left intimate but also common traces within the Iranian diaspora,

like many other diasporas.

[1] I interviewed Dr Persis Karim in December 2022 in Berkeley, United States.

In this piece, I reflect on themes that emerged in an interview with Dr Persis Karim, Iranian-American scholar, poet, and educator, who has been leading critical Iranian diaspora studies initiatives in the United States including the Iranian-American Digital Archive

Project, the subject of our discussion.[1] Karim is Director and the Neda Nobari Endowed Chair of the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies and Professor in the Department of Comparative and World Literature at San Francisco State University (SFSU). In the following, I explore the questions of why community archives are important, how and why Karim went about initiating this archive, collections housed in the digital archive, the

political condition of exile, and some of the challenges faced when carrying out this work.

-

“People mistake the archive with the state, but the real archive lives in the memory of people” – these are words that have stayed with Dr Persis Karim from her visit to the Museum of Innocence in Istanbul in 2015, which she recalled as I asked Karim what led her to think about archiving the stories of Iranian immigrants in the United States as part of her work at the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies. The museum in Istanbul, she told me, cleverly accompanies the novel of the same name, both crafted by the Turkish writer and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk. The museum is filled with everyday objects that Pamuk collected from Istanbul’s flea markets, second-hand shops, and the homes of family and friends. Together, these ordinary, physical objects present an archive of Istanbul in the 1970s, which Pamuk used to form the prose in his novel.

-

“People mistake the archive with the state, but the real archive lives in the memory of people” – these are words that have stayed with Dr Persis Karim from her visit to the Museum of Innocence in Istanbul in 2015, which she recalled as I asked Karim what led her to think about archiving the stories of Iranian immigrants in the United States as part of her work at the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies. The museum in Istanbul, she told me, cleverly accompanies the novel of the same name, both crafted by the Turkish writer and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk. The museum is filled with everyday objects that Pamuk collected from Istanbul’s flea markets, second-hand shops, and the homes of family and friends. Together, these ordinary, physical objects present an archive of Istanbul in the 1970s, which Pamuk used to form the prose in his novel.

[2] The Iranian-American Digital Archive Project can be accessed here: https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/cids

This blurring of conventional history with popular historical memory, and the collection of everyday items from people’s lives to tell a story about the recent past inspired Karim to think about how and why we can archive for our communities. Since 2017, Karim

has been the director of the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies at San Francisco State University (SFSU). One of its initiatives is the Iranian-American Digital Archive Project.[2] The project is a growing archive which currently digitally houses five collections of the Iranian diaspora, focusing on the Iranian community in the San Francisco Bay Area. Through documents, photographs, film, posters, letters, and printed ephemera, it documents parts of the Iranian immigration story, but also contains the histories of Iranian organisations, individuals, and movements that have both been shaped by and shaped the culture, history, and social movements of the Bay Area, and the United States, more broadly.

What are community archives? For Karim, they are “partly sites of memory, but they are also sites of reconstructing a story that may have been buried, or silenced, or maybe not even explored. In that way they are very different than those that house the relics of power, states, institutions and conquest”. As a forward-thinking community archivist, and one who has not been formally trained, she is thinking two generations ahead: in the future, what would someone who doesn’t know anything about Iranians in the Bay Area want to know about this community? They might want to know about the role of the arts, or they may want to know what happened to political leftists who were exiled in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Collecting objects, artefacts, and documents fills this archive with stories that not only deserve a place in the public record, but that are also waiting to be read, written, and retold for future generations who might be interested in this history.

Any single object or item contains its own individual story and reveals a much bigger narrative about its time – this is something that Karim knows through her own experience of her family history. Unlike the majority of Iranians in the United States who migrated after the Iranian Revolution of 1979, her father arrived in the United States and became a sort of accidental immigrant in 1946, after living through the Russian and British occupation of Iran. Karim was born in 1962 in a sleepy suburb of San Francisco. While many born in the diaspora learn about their national history primarily through their parents and family, she was underexposed to Iranian culture and history because of how few Iranians her family knew. Her mother was not Iranian, but French. Nearly two decades after the 1979 revolution, Karim decided to study Iranian history in graduate school. It was eye-opening and surprising to her that only near the end of her father’s life did he choose to show her a photo – a large photograph of him beside Mohammad Reza Shah, when he was working as an engineer during construction and expansion of the Iranian national railway during World War II. “I think he was embarrassed of it because he disliked the Shah. But that photograph also made me understand that my father’s history of leaving Iran was part of my history too, and I am impacted by the way he narrates his story. Within this photo was a story that was unknown to me, in which he narrated about his experience of the Anglo-Soviet occupation of Iran during the Second World War, of Iran being pulled into a Cold War game, and how he perceived the overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh”.

Karim’s motivation for the archive also grows out of the awareness she witnessed as she became more connected to Iranians in the Bay Area. Like other immigrant communities, Iranians have experienced multiple and various forms of loss, pain, trauma, and violence. It is difficult for first-generation immigrants in particular to talk about aspects of their past. There is often melancholy or nostalgia – affects, in other words, deeply emotional and human responses to real-world structures and experiences. One of the things that most struck me in speaking to Karim was the transformative potential of the diaspora archive – “how it allows people to see their own stories in other people’s stories”. She adds that it is important for individuals to know that “they have a story, and that theirs might be part of a bigger story, and can be found in things like objects, documents, and letters”. Many people in the diaspora – primarily due to factors of class, gender, race, sexuality, etc., subaltern social groupings – would not assume that their story and their baggage – material, emotional, or otherwise, is worthy of historical record, but community archives like the one Karim has initiated show us that there is real historical value – both present and future-orientated – in collecting and preserving people’s stories and histories.

I first met Persis Karim in October 2021 during my time as a visiting researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. She warmly welcomed me to the Bay Area, so generously connected me with people and helped me with my PhD research, and introduced me to the study and archiving of the diaspora. She taught me that there is something important to recognise and study in the familiarity, commonalities, and differences between Iranians across the world that we might take for granted as members of a diaspora. She emphasises how scattered communities challenge the nation-state and help us think about transnationalism in interesting ways, and how the modern history of Iran must also include the complicated histories of diaspora and migration.

My interest in the Iranian-American Digital Archive Project came as I was tracing individuals in my research on Iranian political movements and student activism in the 1970s. One of the individuals whose student and political activities are recorded in this archive is Parviz Shokat. His political organisation in the early 1970s, the Union of Iranian Communists, sent a solidarity activist from the United States to visit the Dhufar Revolution in Oman, where an anticolonial guerrilla movement was being crushed by Anglo-Iranian military intervention. These transnational connections are only rendered visible when tracing the lives and movements of individuals – whose stories and histories are not found in archives in Iran where the history of the Iranian Left has been repressed and destroyed. And, they are almost impossible to find in the typical archives of the United States. The diaspora archive is essential in documenting the histories of Iranians whose stories may remain untold and which we risk losing as the first generation of Iranians displaced by the Iranian Revolution of 1979 are passing away.

What are community archives? For Karim, they are “partly sites of memory, but they are also sites of reconstructing a story that may have been buried, or silenced, or maybe not even explored. In that way they are very different than those that house the relics of power, states, institutions and conquest”. As a forward-thinking community archivist, and one who has not been formally trained, she is thinking two generations ahead: in the future, what would someone who doesn’t know anything about Iranians in the Bay Area want to know about this community? They might want to know about the role of the arts, or they may want to know what happened to political leftists who were exiled in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Collecting objects, artefacts, and documents fills this archive with stories that not only deserve a place in the public record, but that are also waiting to be read, written, and retold for future generations who might be interested in this history.

Any single object or item contains its own individual story and reveals a much bigger narrative about its time – this is something that Karim knows through her own experience of her family history. Unlike the majority of Iranians in the United States who migrated after the Iranian Revolution of 1979, her father arrived in the United States and became a sort of accidental immigrant in 1946, after living through the Russian and British occupation of Iran. Karim was born in 1962 in a sleepy suburb of San Francisco. While many born in the diaspora learn about their national history primarily through their parents and family, she was underexposed to Iranian culture and history because of how few Iranians her family knew. Her mother was not Iranian, but French. Nearly two decades after the 1979 revolution, Karim decided to study Iranian history in graduate school. It was eye-opening and surprising to her that only near the end of her father’s life did he choose to show her a photo – a large photograph of him beside Mohammad Reza Shah, when he was working as an engineer during construction and expansion of the Iranian national railway during World War II. “I think he was embarrassed of it because he disliked the Shah. But that photograph also made me understand that my father’s history of leaving Iran was part of my history too, and I am impacted by the way he narrates his story. Within this photo was a story that was unknown to me, in which he narrated about his experience of the Anglo-Soviet occupation of Iran during the Second World War, of Iran being pulled into a Cold War game, and how he perceived the overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh”.

Karim’s motivation for the archive also grows out of the awareness she witnessed as she became more connected to Iranians in the Bay Area. Like other immigrant communities, Iranians have experienced multiple and various forms of loss, pain, trauma, and violence. It is difficult for first-generation immigrants in particular to talk about aspects of their past. There is often melancholy or nostalgia – affects, in other words, deeply emotional and human responses to real-world structures and experiences. One of the things that most struck me in speaking to Karim was the transformative potential of the diaspora archive – “how it allows people to see their own stories in other people’s stories”. She adds that it is important for individuals to know that “they have a story, and that theirs might be part of a bigger story, and can be found in things like objects, documents, and letters”. Many people in the diaspora – primarily due to factors of class, gender, race, sexuality, etc., subaltern social groupings – would not assume that their story and their baggage – material, emotional, or otherwise, is worthy of historical record, but community archives like the one Karim has initiated show us that there is real historical value – both present and future-orientated – in collecting and preserving people’s stories and histories.

I first met Persis Karim in October 2021 during my time as a visiting researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. She warmly welcomed me to the Bay Area, so generously connected me with people and helped me with my PhD research, and introduced me to the study and archiving of the diaspora. She taught me that there is something important to recognise and study in the familiarity, commonalities, and differences between Iranians across the world that we might take for granted as members of a diaspora. She emphasises how scattered communities challenge the nation-state and help us think about transnationalism in interesting ways, and how the modern history of Iran must also include the complicated histories of diaspora and migration.

My interest in the Iranian-American Digital Archive Project came as I was tracing individuals in my research on Iranian political movements and student activism in the 1970s. One of the individuals whose student and political activities are recorded in this archive is Parviz Shokat. His political organisation in the early 1970s, the Union of Iranian Communists, sent a solidarity activist from the United States to visit the Dhufar Revolution in Oman, where an anticolonial guerrilla movement was being crushed by Anglo-Iranian military intervention. These transnational connections are only rendered visible when tracing the lives and movements of individuals – whose stories and histories are not found in archives in Iran where the history of the Iranian Left has been repressed and destroyed. And, they are almost impossible to find in the typical archives of the United States. The diaspora archive is essential in documenting the histories of Iranians whose stories may remain untold and which we risk losing as the first generation of Iranians displaced by the Iranian Revolution of 1979 are passing away.

[3] ‘Mounting Pressure to Release Iranian Students’, Bay Area

Television Archive, 30 June 1970, available: https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/238283

[4] The strikes changed Higher Education in the United States by establishing the discipline of Ethnic Studies, see: https://www.kqed.org/news/11830384/how-the-longest-student-strike-in-u-s-history-created-ethnic-studies

[5] Manijeh Moradian, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022); Ida Yalzadeh, “‘Support the 41’: Iranian Student Activism in Northern California, 1970-3,” in Matthew Shannon, ed., American-Iranian Dialogues: From Constitution to White Revolution, c. 1890s-1960s, 167-182 (New York: Bloomsbury, 2021).

[4] The strikes changed Higher Education in the United States by establishing the discipline of Ethnic Studies, see: https://www.kqed.org/news/11830384/how-the-longest-student-strike-in-u-s-history-created-ethnic-studies

[5] Manijeh Moradian, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022); Ida Yalzadeh, “‘Support the 41’: Iranian Student Activism in Northern California, 1970-3,” in Matthew Shannon, ed., American-Iranian Dialogues: From Constitution to White Revolution, c. 1890s-1960s, 167-182 (New York: Bloomsbury, 2021).

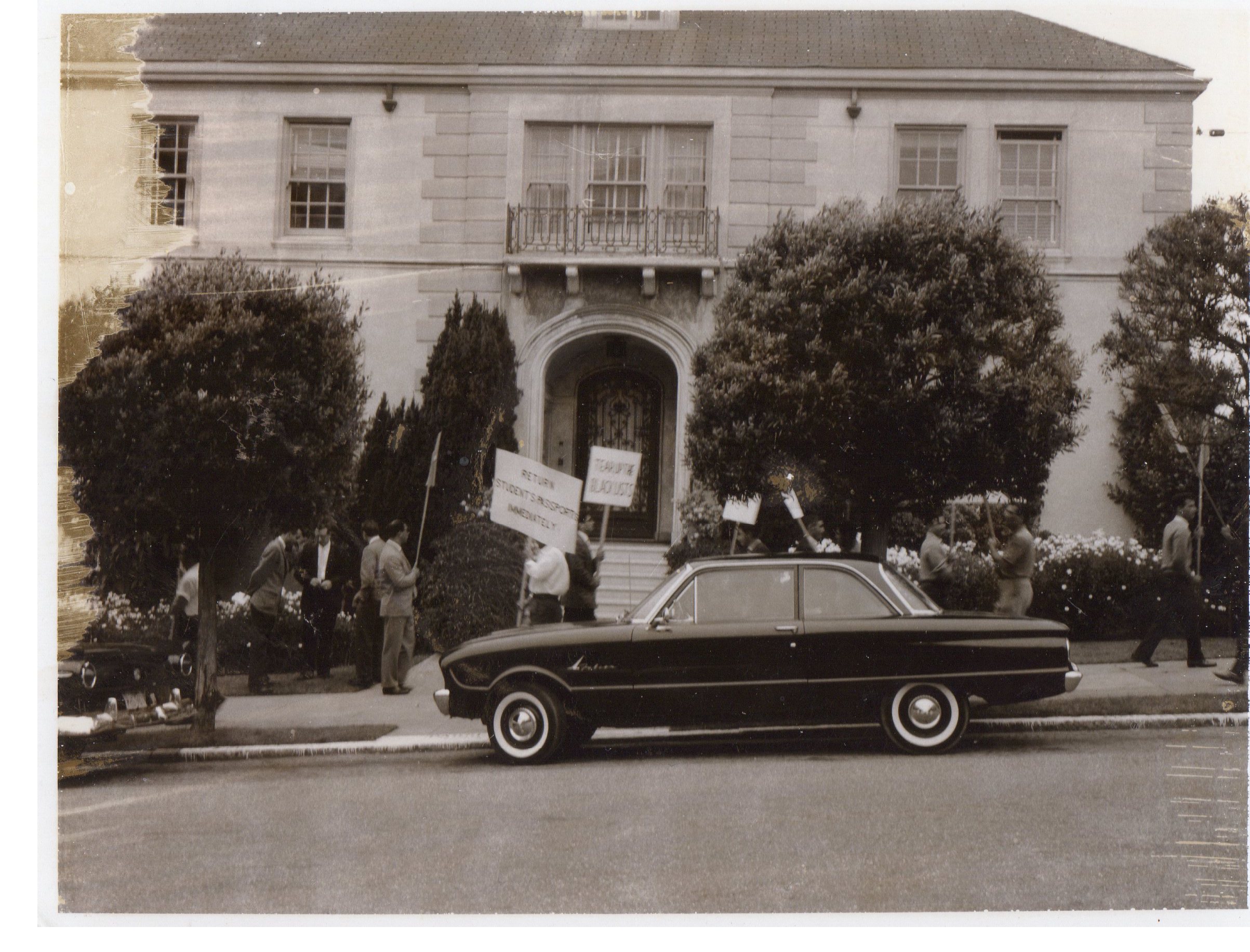

The Parviz Shokat collection in the

Iranian-American Digital Archive Project includes a small number of documents

and photographs from his life, including the court document recounting the

crimes of 41 Iranian students who stormed the Iranian consulate in San

Francisco in 1970. Shokat was one of the 41 who risked detention and

deportation for protesting the Shah’s repressive rule, but as an Iranian

student demonstrator explained on rare video footage from the Bay Area

Television Archive, student demonstrators had been peacefully protesting and

wanted to interview the Shah’s sister about political repression in Iran.[3] Parviz Shokat was a member of the Northern California Branch of the Iranian

Students’ Association, the US affiliate of the global coalition, the

Confederation of Iranian Students, National Union (CISNU), who organised the

largest political opposition movement abroad against the Shah of Iran. Shokat

participated in the significant 1968-69 strikes and occupation at San Francisco

State University alongside the Black Student Union and Third World Liberation

Front.[4] Scholars have Shokat’s materials in their ground-breaking academic work on the

history of the Iranian diaspora in the United States. Manijeh Moradian has powerfully

theorised how the “revolutionary affects” of different organising groups,

including Iranian and other students, led to “affects of solidarity” which

sustained Third World internationalism, and Ida Yalzadeh has explored Iranian

racialisation in the United States through the political activism of the 41

students.[5]

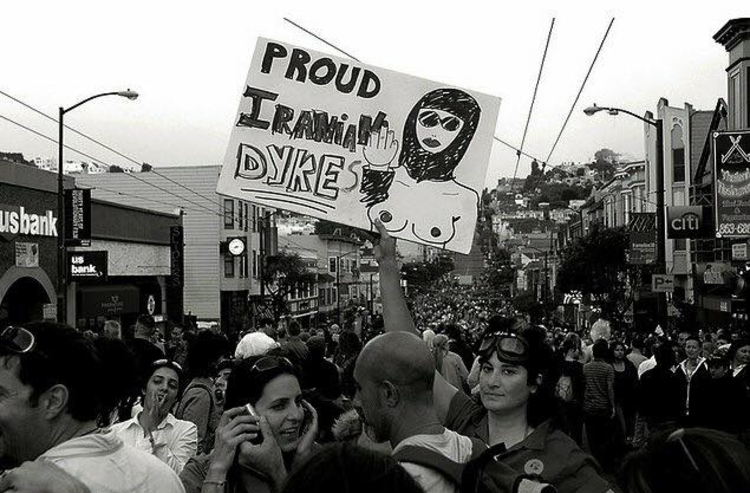

How does Karim go about archiving the stories of those like Parviz Shokat? The collection online is small in comparison to Shokat’s extensive collection of materials from the Iranian Left housed in the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, but the project’s aim is not to replicate existing archives, instead, it is built on what is shared from members of their community in San Francisco. Karim and project assistants work on sorting, scanning, and digitising shared materials. The project’s digital format means that it is far more accessible than collections stored in physical archives, and at the time of writing the Iranian-American Digital Archive Project had amassed almost 60,000 views. Another collection is the HASHA collection, which features materials from the queer community of Iranian descent in the Bay Area, and holds stories of their activism, organising, and community-building work. This is an archive which is not only of the diaspora, but is for the diaspora, and two graduate students have recently used these materials in their academic work.

How does Karim go about archiving the stories of those like Parviz Shokat? The collection online is small in comparison to Shokat’s extensive collection of materials from the Iranian Left housed in the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, but the project’s aim is not to replicate existing archives, instead, it is built on what is shared from members of their community in San Francisco. Karim and project assistants work on sorting, scanning, and digitising shared materials. The project’s digital format means that it is far more accessible than collections stored in physical archives, and at the time of writing the Iranian-American Digital Archive Project had amassed almost 60,000 views. Another collection is the HASHA collection, which features materials from the queer community of Iranian descent in the Bay Area, and holds stories of their activism, organising, and community-building work. This is an archive which is not only of the diaspora, but is for the diaspora, and two graduate students have recently used these materials in their academic work.

[6] Shahrzad Mojab, “Figures of Dissent: Women’s Memoirs of Defiance”, in

Alison Crosby and Heather Evans, eds., Remembering and Memorializing Violence:

Transnational Feminist Dialogues, forthcoming.

One of the striking

themes embedded in this archive, and many archives of diaspora,

is the complicated location of exile.

What does it mean to archive the political condition of exile? After the

Iranian Revolution of 1979, many Iranians found themselves in exile, expecting

to return to Iran under different political circumstances. The line between

exile and diaspora can be contentious, as some Iranians in the diaspora today

occupy a status of exile and refuse to accept their position in the diaspora. “There

is a stunning pain in the interminable nature of the ‘diaspora’, while ‘exile’

is a conscious reminder of a great wound of expulsion caused by the state”,

writes the scholar and activist, Shahrzad Mojab.[6] There is something ironically settled and permanent about accepting your status

in the diaspora – as a people who are here to stay, which is why some of the

stories of resistance within exile in an archive of diaspora occupy a liminal

space. Yet, like the literal space that diaspora can provide, stories of exile

find a home in the diaspora archive. Karim says that “immigration causes a

rupture in people’s history”, and it is important to document the thread of

connection between the past and present. These experiences and histories must

be documented somewhere, more so in the event of forced migration and exile.

The archive’s digital collections includes materials from the Darvag Theatre Company, a small Farsi-speaking theatre group launched in 1985. Like many of the theatre groups that emerged in Berkeley the 1960s and 1970s, they were interested in the Brechtian understanding of theatre as a radical form of political expression for ordinary people rather than the typical elite audience. The group emerged from a collective of individuals who had been members of the student movement and left-wing Iranian political parties such as the Tudeh Party and Fada’iyan, and had left Iran under duress and experienced the loss of friends and comrades. They didn’t form the group with an interest to produce theatre, instead, they realised that they had stories to share, and theatre became a vehicle to process their trauma. The experience of exile, immigration, and the afterlives of revolution repeatedly unfold in the group’s plays, such as in Chamedan (The Suitcase) which brought the personal experience of the Iranian community in exile in the Bay Area to a wider audience. What Karim finds interesting in the history of this theatre group is the remnants of the political processes that lie within the collective. The group, she tells me, has played an important role in the Bay Area – by bringing people into their particular experience of loss and pain, and even alienation, they have built a stronger community.

In doing the work of building a public record of the Iranian-American immigrant experience, the Iranian-American Digital Archive Project follows the example of other diaspora communities in the United States such as the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies at North Carolina State University which has digital and physical archives. While conducting initial outreach work to collect materials, Karim thought that asking people to share their family stories, photography, and documents at Iranian community events would stimulate interest in the archive. However, she was met with suspicion from many people who questioned why they should share their personal stories, an understandable response from a migrant community that has experienced various layers of state surveillance and violence. While the Center houses a community archive, it is based at a university institution and has received national funding; the Center won a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Digital Humanities Grant in 2019. Maintaining the funding itself has been another challenge for the Center – something I found surprising given that it feels like there are more resources and opportunities in the United States, in comparison to other parts of the world.

The archive’s digital collections includes materials from the Darvag Theatre Company, a small Farsi-speaking theatre group launched in 1985. Like many of the theatre groups that emerged in Berkeley the 1960s and 1970s, they were interested in the Brechtian understanding of theatre as a radical form of political expression for ordinary people rather than the typical elite audience. The group emerged from a collective of individuals who had been members of the student movement and left-wing Iranian political parties such as the Tudeh Party and Fada’iyan, and had left Iran under duress and experienced the loss of friends and comrades. They didn’t form the group with an interest to produce theatre, instead, they realised that they had stories to share, and theatre became a vehicle to process their trauma. The experience of exile, immigration, and the afterlives of revolution repeatedly unfold in the group’s plays, such as in Chamedan (The Suitcase) which brought the personal experience of the Iranian community in exile in the Bay Area to a wider audience. What Karim finds interesting in the history of this theatre group is the remnants of the political processes that lie within the collective. The group, she tells me, has played an important role in the Bay Area – by bringing people into their particular experience of loss and pain, and even alienation, they have built a stronger community.

In doing the work of building a public record of the Iranian-American immigrant experience, the Iranian-American Digital Archive Project follows the example of other diaspora communities in the United States such as the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies at North Carolina State University which has digital and physical archives. While conducting initial outreach work to collect materials, Karim thought that asking people to share their family stories, photography, and documents at Iranian community events would stimulate interest in the archive. However, she was met with suspicion from many people who questioned why they should share their personal stories, an understandable response from a migrant community that has experienced various layers of state surveillance and violence. While the Center houses a community archive, it is based at a university institution and has received national funding; the Center won a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Digital Humanities Grant in 2019. Maintaining the funding itself has been another challenge for the Center – something I found surprising given that it feels like there are more resources and opportunities in the United States, in comparison to other parts of the world.

[7] Orhan Pamuk, ‘State museums are so antiquated’, The Guardian, 20

April 2012, available: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/apr/20/orhan-pamuk-make-museums-much-smaller

When I asked Karim why the archive

focuses on the Bay Area and not the United States, I assumed that this had

something to do with the issue of funding. But she responded by suggesting that

it is also important to preserve local stories. “The archive is not attempting

to be a grand and comprehensive record of everything, instead, it is rooted in

one local community and its particular story – that particularity is what makes

it relatable and interesting for people from that area, and universally

understood from the diaspora’s different locations”, she explained. The

scattered nature of the diaspora in a way requires us to act locally, it is not

fixed in one place but is anchored in its locales. The initial collections in

the archive have been gathered through personal connections with people within

the community. This ‘local’ rooting of the archive is comparably found in Orhan

Pamuk’s manifesto on challenging large, national museums with smaller ones, who

writes: “We all know that the ordinary, everyday stories of individuals are

richer, more humane and much more joyful than the stories of colossal

cultures”.[7]

In diaspora, the deeply intricate and complicated stories of exile, of pain, of trauma, of joy, and of celebration, are far more nuanced and valuable to our collective understanding of ourselves, of how we got here and where we go from here. This is an archive that disrupts the typical narratives of ‘model minority’ immigrants and which cannot be a linear story of arrival, settlement, and success, because the history of the Iranian diaspora is one of resistance and rupture. The Iranian-American Digital Archive Project allows us to think seriously about how diaspora communities in other parts of the world can go about engaging in similar archival work, towards building a shared inventory.

In my academic research on the modern history of Iran, I have found traces of the stories of my parents and their friends in the archives and histories of others, and experienced first-hand how showing single objects – pamphlets, documents, photographs, has reactivated something in them and prompted them to remember and recall their buried and often difficult experiences from the past. This is a privilege that I should not be afforded simply because I am working on Iranian history at an academic level – it ought to be available to all, and this is what motivates me to think practically about what an archive for the Iranian community in London, where I am based, might look like. Diaspora communities have so many stories to tell, especially from the people who may not recognise the value of their personal history and experiences for history and for the future.

In diaspora, the deeply intricate and complicated stories of exile, of pain, of trauma, of joy, and of celebration, are far more nuanced and valuable to our collective understanding of ourselves, of how we got here and where we go from here. This is an archive that disrupts the typical narratives of ‘model minority’ immigrants and which cannot be a linear story of arrival, settlement, and success, because the history of the Iranian diaspora is one of resistance and rupture. The Iranian-American Digital Archive Project allows us to think seriously about how diaspora communities in other parts of the world can go about engaging in similar archival work, towards building a shared inventory.

In my academic research on the modern history of Iran, I have found traces of the stories of my parents and their friends in the archives and histories of others, and experienced first-hand how showing single objects – pamphlets, documents, photographs, has reactivated something in them and prompted them to remember and recall their buried and often difficult experiences from the past. This is a privilege that I should not be afforded simply because I am working on Iranian history at an academic level – it ought to be available to all, and this is what motivates me to think practically about what an archive for the Iranian community in London, where I am based, might look like. Diaspora communities have so many stories to tell, especially from the people who may not recognise the value of their personal history and experiences for history and for the future.

Marral Shamshiri is

a PhD candidate in International History at the London School

of Economics. She is interested in the histories of socialism and

internationalism, Third Worldism and the global cold war. Her current

project looks at the history of the Iranian Left, focusing on the

transnational and political connections between Iranian

and Arab revolutionary movements in the long 1960s and 1970s. She is

co-editor of the book She Who Struggles (Pluto Press, 2023).

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎ ︎

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎ ︎