Annabelle Aventurin

Archival inquiry and anticolonial militant cinema:

Reflections on Guadeloupe Answers Back

I did not learn about the existence of the film Guadeloupe répond through conversations with my family members in Guadeloupe, friends, or within the sphere of militant cinema archives, which I had frequented for many years as an archivist at Ciné-Archives, the film collection of the French Communist Party and the labor movement. Its trace appeared to me through other channels.

The starting point was Amsterdam in 2021, during a symposium organized at the Eye Film Museum. Dutch researcher Luna Hupperetz was presenting her work on the digital restoration of the collective and militant film Oema foe Sranan / Women of Suriname (1978). This film, produced by Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms (Freedom Films Cine Club) and LOSON (National Consultation of Surinamese Organisations in the Netherlands), documented the country’s recent independence. The film is about four women whose personal stories recounted the history of colonialism, neo-colonialism, imperialism, and racism in the Netherlands. At the symposium, my encounters with Luna and Nadia Tilon, Surinamese artists and activists who had worked on the film’s editing and soundtrack, allowed me to grasp the significance of these transnational militant archives. Hupperetz’s thesis on the militant circuit of Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms had led her to consult the ciné-club’s papers, preserved at the International Institute of Social History (IIHS), where the trace of a film on Guadeloupe also appeared. It was in this context that I first heard about it.

In the 1960s and 70s militant film scene, films were often shown without subtitles. To make them accessible, transcripts were prepared in several languages and read aloud during screenings. In the case of Guadeloupe Répond, English–Dutch transcripts were preserved in the IIHS archives. When I opened this set of documents, several elements stood out to me.

On the first page was written “Biri A/S Biri Norway.” This directed my research toward Norwegian archives, under the assumption that the film might be located there as I was extremely eager to find a way to see the film.

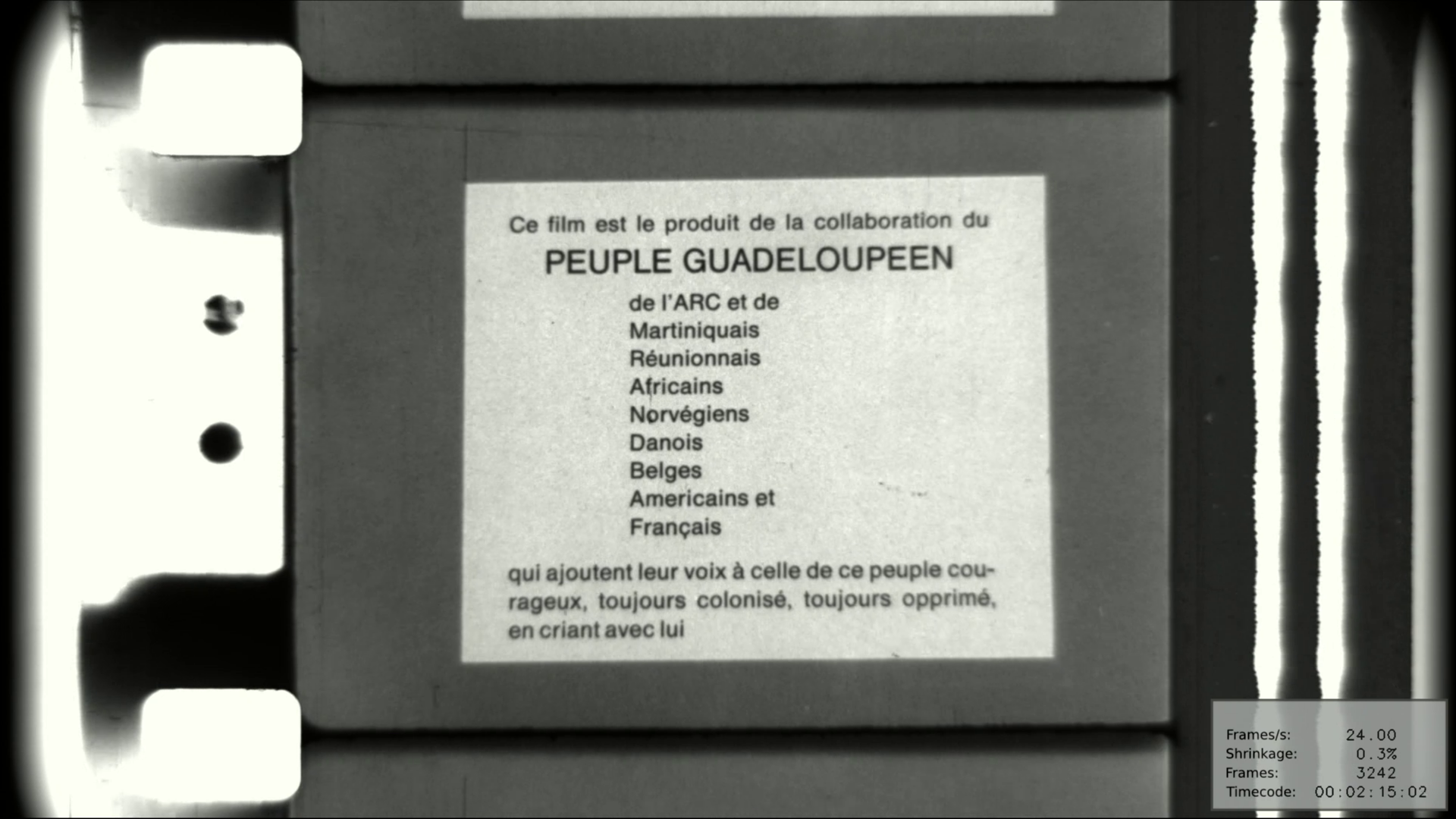

On the second page, several nationalities of people that collaborate to the film were listed as followed :

I immediately realized that there would be a film, potentially a documentary, about the uprising of May 1967 in Guadeloupe.

It also mentioned Atelier de recherches cinématographiques (ARC), a militant film collective very active in the making of footage of the 1968 uprising in France.

The starting point was Amsterdam in 2021, during a symposium organized at the Eye Film Museum. Dutch researcher Luna Hupperetz was presenting her work on the digital restoration of the collective and militant film Oema foe Sranan / Women of Suriname (1978). This film, produced by Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms (Freedom Films Cine Club) and LOSON (National Consultation of Surinamese Organisations in the Netherlands), documented the country’s recent independence. The film is about four women whose personal stories recounted the history of colonialism, neo-colonialism, imperialism, and racism in the Netherlands. At the symposium, my encounters with Luna and Nadia Tilon, Surinamese artists and activists who had worked on the film’s editing and soundtrack, allowed me to grasp the significance of these transnational militant archives. Hupperetz’s thesis on the militant circuit of Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms had led her to consult the ciné-club’s papers, preserved at the International Institute of Social History (IIHS), where the trace of a film on Guadeloupe also appeared. It was in this context that I first heard about it.

In the 1960s and 70s militant film scene, films were often shown without subtitles. To make them accessible, transcripts were prepared in several languages and read aloud during screenings. In the case of Guadeloupe Répond, English–Dutch transcripts were preserved in the IIHS archives. When I opened this set of documents, several elements stood out to me.

On the first page was written “Biri A/S Biri Norway.” This directed my research toward Norwegian archives, under the assumption that the film might be located there as I was extremely eager to find a way to see the film.

On the second page, several nationalities of people that collaborate to the film were listed as followed :

This film is the result of the collaboration of THE PEOPLE OF GUADELOUPE, of ARC, of Martiniquans, of Réunionians, of Africans, of Norwegians, of Danes, of Belgians, of Americans, of French who add their voice to that of this courageous people, colonized, still oppressed, in crying out with them LONG LIVE FREE GUADELOUPE !

I immediately realized that there would be a film, potentially a documentary, about the uprising of May 1967 in Guadeloupe.

It also mentioned Atelier de recherches cinématographiques (ARC), a militant film collective very active in the making of footage of the 1968 uprising in France.

After several inquiries to different Norwegian institutions, the Nasjonalbiblioteket (National Library of Norway) confirmed that a film titled Vive la Guadeloupe libre had indeed been preserved, attributed to a certain Carolyn Swetland. They told me Biri A/S was the name of the company she created in 1967 (in the course of the making of the film I got to know that it was also the name of her hometown in Norway). I assumed they had no other item related to Guadeloupe and they soon confirmed that it’s the film I was looking for.

Experience with collective militant films invites caution: these works are often anonymized, their creators working for a cause and as a collective rather than for personal recognition. Yet decades later, internal tensions sometimes resurface, either conflicts of ego or disagreements around preserving the film emerge, and collective works may be reattributed or appropriated by a single person. In this case, however, it appeared primarily to be a matter of archival deposit for preservation, as would later be confirmed by the film credits itself.

My correspondent at the National Library also gave me some details about her:

By mixing the ARC lead to Swetland, I was able to find out that she participated in the shooting of Kimbé red pa moli (1971)1, a militant short animation film co-directed by Jean-Denis Bonan and Mireille Abramovici, thanks to an interview conducted by Elias Herody for the journal Débordements in connection with his research in May 1968. In an article published in January 2023, Herody quotes Bonan:

This testimony confirms the film’s existence and Swetland’s involvement. In a later interview, Bonan specified that Biri was also her pseudonym in her activities as a militant filmmaker in Paris.

Vive la Guadeloupe libre

After several months of emailing with my correspondent at the National Library, I was lucky enough, and with great emotion, to finally see a rough digitization of the film that is, at the moment, not final nor released.

The film is set in the postcolonial context of Guadeloupe, immediately after the May 1967 uprisings. These events began on May 26 with a strike by Guadeloupean construction workers demanding a 2.5% wage increase. Their request was denied. Shortly after, a racist attack on a Guadeloupean by a béké (descendant of white colonial settlers in Guadeloupe) and his dog took place, leading to the police protecting the béké. These events led to an uprising of Guadeloupeans in May 1967, known now as Mé 67, and a violent repression from state police which led to around one hundred deaths, including of Jacques Nestor,3 a GONG member, targeted and assassinated by the police in the street.

In January 1968 a trial of the nineteen GONG militants, accused of moral responsibility for the events in Guadeloupe, took place in Paris. They were prosecuted for pro-independence propaganda. The verdict (acquittal with suspended sentences) was intended to contain the uprisings. The French state, for its part, was never held accountable. Only in 2016, in a report by French historian Benjamin Stora commissioned by former president François Hollande, were the events qualified as a “massacre.”

Experience with collective militant films invites caution: these works are often anonymized, their creators working for a cause and as a collective rather than for personal recognition. Yet decades later, internal tensions sometimes resurface, either conflicts of ego or disagreements around preserving the film emerge, and collective works may be reattributed or appropriated by a single person. In this case, however, it appeared primarily to be a matter of archival deposit for preservation, as would later be confirmed by the film credits itself.

My correspondent at the National Library also gave me some details about her:

Swetland was an American-Norwegian social anthropologist and also a writer; she came to Norway in 1960 and lived both in Oslo and Paris as you wrote. She was involved in an association for foreign workers in Norway (Fremmedarbeiderforeningen). Her first published work as a writer was a children's book: Bedre enn en kamel, (Better than a camel) and her last novel she wrote shortly before she died in 1995 at an age of 81 years.*

By mixing the ARC lead to Swetland, I was able to find out that she participated in the shooting of Kimbé red pa moli (1971)1, a militant short animation film co-directed by Jean-Denis Bonan and Mireille Abramovici, thanks to an interview conducted by Elias Herody for the journal Débordements in connection with his research in May 1968. In an article published in January 2023, Herody quotes Bonan:

“It was the late 1960s. Mireille and I had become close to a woman named Carolyn Swetland, a Norwegian, a writer—though we did not know it at the time—who had made a film about GONG.2 There was a major trial at the time; they were accused of conspiracy against the state and later acquitted. It was front-page news in Le Monde. She was in contact with African and Caribbean activist circles. We wanted to go to Guadeloupe but had no funds. She told us that Guadeloupean activists had contacted her about making a film. She had a Super 8 camera. At the time, I was doing a lot of drawing. I told her we could perhaps make a film using figurines.”

This testimony confirms the film’s existence and Swetland’s involvement. In a later interview, Bonan specified that Biri was also her pseudonym in her activities as a militant filmmaker in Paris.

Vive la Guadeloupe libre

After several months of emailing with my correspondent at the National Library, I was lucky enough, and with great emotion, to finally see a rough digitization of the film that is, at the moment, not final nor released.

The film is set in the postcolonial context of Guadeloupe, immediately after the May 1967 uprisings. These events began on May 26 with a strike by Guadeloupean construction workers demanding a 2.5% wage increase. Their request was denied. Shortly after, a racist attack on a Guadeloupean by a béké (descendant of white colonial settlers in Guadeloupe) and his dog took place, leading to the police protecting the béké. These events led to an uprising of Guadeloupeans in May 1967, known now as Mé 67, and a violent repression from state police which led to around one hundred deaths, including of Jacques Nestor,3 a GONG member, targeted and assassinated by the police in the street.

In January 1968 a trial of the nineteen GONG militants, accused of moral responsibility for the events in Guadeloupe, took place in Paris. They were prosecuted for pro-independence propaganda. The verdict (acquittal with suspended sentences) was intended to contain the uprisings. The French state, for its part, was never held accountable. Only in 2016, in a report by French historian Benjamin Stora commissioned by former president François Hollande, were the events qualified as a “massacre.”

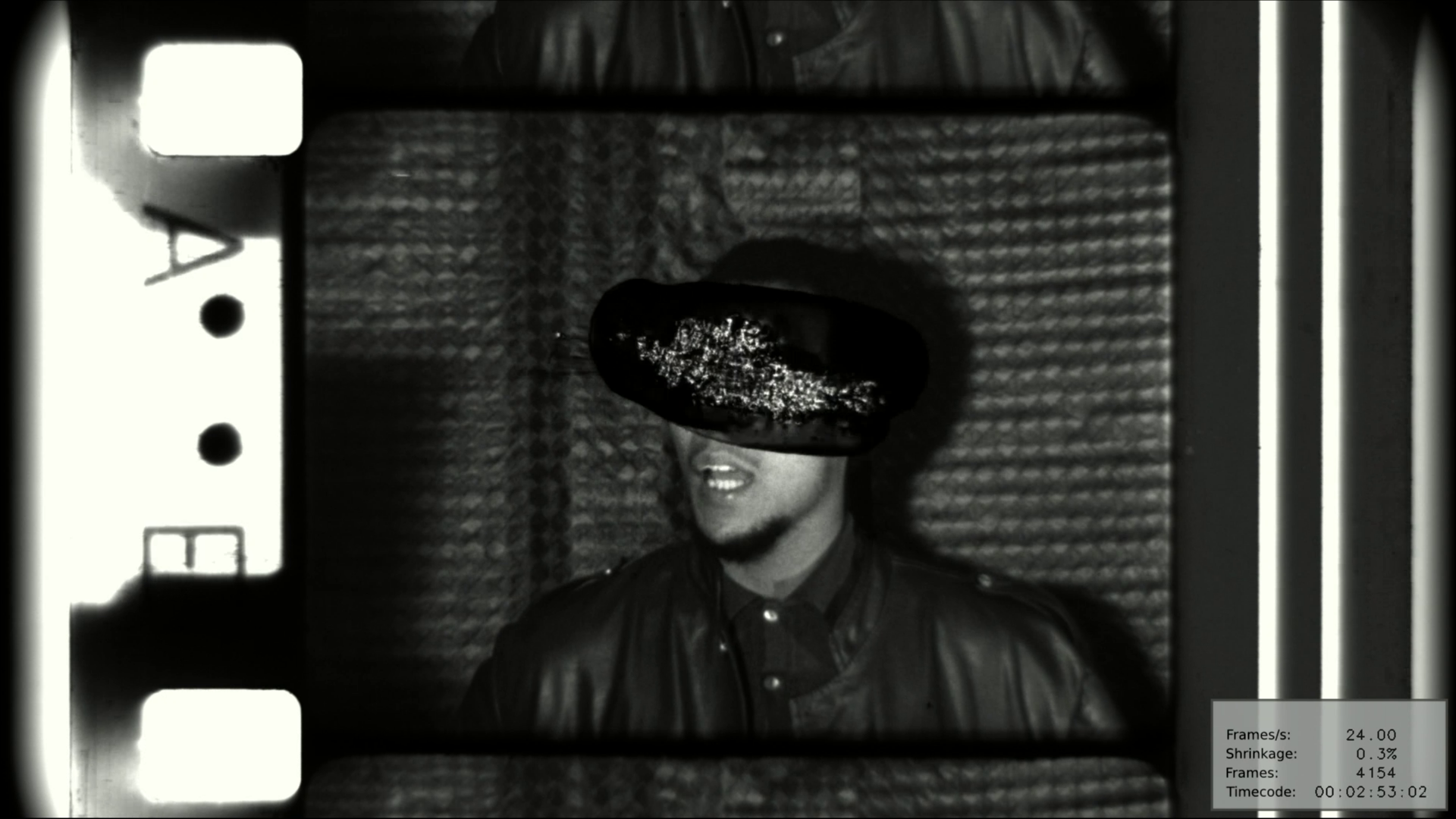

The film draws directly on this trial. The accused appear masked or blindfolded, but what struck me was to witness a direct-on-film intervention technique in order to draw a mask around the eyes of the accused, which in my knowledge is not used in the visual codes of militant cinema of the 1960s-70s.

While watching the film, I had in mind Now! by Santiago Álvarez, a Cuban film defending the American civil rights movement through a montage of still images and militant music. Similarly, Guadeloupe répond uses zooms and superimpositions. The film highlights a specific soundtrack: the contribution by Guadeloupe’s famous Gwoka* musician Robert Loyson, whose song Kann a la richès critiques the colonial sugarcane system established in the mid-1960s by president Pompidou:

While watching the film, I had in mind Now! by Santiago Álvarez, a Cuban film defending the American civil rights movement through a montage of still images and militant music. Similarly, Guadeloupe répond uses zooms and superimpositions. The film highlights a specific soundtrack: the contribution by Guadeloupe’s famous Gwoka* musician Robert Loyson, whose song Kann a la richès critiques the colonial sugarcane system established in the mid-1960s by president Pompidou:

Yo pa kalkilé, yo pa réfléchi, yo sinyé kann a la richès, yo sinyé mizè a la Gwadloup

They didn’t calculate, they didn’t think, they signed “sugarcane for wealth,” but they really signed “poverty for Guadeloupe.

Gaps remain: it is difficult to determine how many copies circulated, through which networks, and if a Guadeloupean audience saw the film. During his interview, Bonan, for instance, stated he saw the film in Paris, with a few happy militants in her flat on Rue Gabrielle. He told me he found several copies of his film Kimbé Red in a Guadeloupean psychiatrist's attic in the early 2000, which somehow gave hope to find more copies of Swteland’s film too.

Today, the hope is to obtain the digitization of the 16mm print and restoration of Guadeloupe répond so that it can circulate again. The goal is not only to make it available but to open a space for discussion in Guadeloupe around its screening, as the film, almost entirely in Guadeloupean creole, is ready to circulate in its current state. The film, recounting the Mé 1967 uprising and trial and inscribing their struggle within a transnational militant aesthetic, is a precious resource for understanding international solidarities and anti-colonial struggles of the 1960s-70s.

From Dutch cine-clubs documenting post-independence Surinamese struggles to Guadeloupean exiles in Paris collaborating with French and Norwegian filmmakers, these films reveal a dense web of exchanges, collaboration, and mutual support across borders, languages, and continents.

Guadeloupe répond production involved collaboration among Guadeloupeans, French, Norwegians, Danes, Belgians and others, reflecting a collective effort to document and support anti-colonial struggles. This aligns with the vision of filmmakers René Vautier and Nicole Le Garrec, who, in the early 1970s, initiated the Caméras dans le combat4 project. Intended to showcase politically committed cinema from around the world, including works from Sweden, Japan, Palestine, and Cuba, the project aimed to highlight how cinema was utilized in social, labor, and revolutionary struggles. Although the project was never completed, it laid the groundwork for future endeavors in documenting global militant cinema.

It also helps us to know more about an intentionally marginalized memory, as May 1968 is taught in schools while the uprising remained silenced. Trying to find the film print reminded me of how militant cinema, thanks to its circulation, has sometimes found a way to preserve itself through the scattered prints existing across archives in multiple countries or in someone's attic.

Guadeloupe répond is simultaneously a testimony of colonial repression, a record of a trial and a struggle, a collective work, and a fragment of a broader history. By following the delicate threads left in the archives, it becomes possible to reconstruct this trajectory : not to fix a definitive narrative, but to reopen a space of memory and circulation.

Footnotes

1. Kimbe red pa moli ! — a Guadeloupean Creole expression meaning “Hold on, don’t give up!” — is an animated film.

Directed by Jean-Denis Bonan, in close collaboration with Mireille Abramovici and Caroline Biri (Sewteland pseudo), Kimbe red pa moli! bridges the struggles of post-1968 France and the 1970 sugarcane workers’ strike in Guadeloupe. Produced within the orbit of the Atelier de recherches cinématographiques (ARC) and later Cinélutte, the film embodies the political and aesthetic experiments of the French militant cinema of the 1970s.

Unable to travel to Guadeloupe for lack of funds, the filmmakers turned to animation ; clay figurines and cardboard sets, to reimagine a distant workers’ struggle.

2. Groupe d’Organisation Nationale de la Guadeloupe (GONG). The first Guadeloupean nationalist organization was founded in Paris in June 1963, at the initiative of a generation of students who had developed their nationalist education within the AGEG (Association Générale des Étudiants Guadeloupéens) and in the international anti-imperialist student movement, then within the Front antillo-guyanais pour l’autodétermination (1960–1961). The GONG emerged as a typical national liberation political organization of the 1960s: essentially Third-Worldist in its initial inspiration, it was also significantly influenced by the Algerian Revolution and Maoist ideology.

(Translation of a note by Jean-Pierre Sainton, pp. 16–17, in Elsa Dorlin, Guadeloupe Mai 67. Massacrer et laisser mourir, Libertalia, 2023.)

3. Jacques Nestor (1941–1967) was a fisherman and nationalist activist, a member of the Pointe-à-Pitre group of the Gong. An active militant deeply involved in grassroots action, Nestor participated in all of the Gong’s agitation and propaganda activities between 1965 and 1967, and became well known to the police. A quintessential mass leader, he stood at the forefront of the demonstrations on May 26, 1967, where he was targeted and fatally shot at the very beginning of the clashes. News of his death played a major role in sparking the uprising among young people from working-class neighborhoods, where he was well known and widely respected.

(Translation of a note by Jean-Pierre Sainton, pp. 16–17, in Elsa Dorlin, Guadeloupe Mai 67. Massacrer et laisser mourir, Libertalia, 2023.)

4. In 2024, researcher and curator Léa Morin and I presented one of our Non-Aligned Film Archives programs at Open City London, which revisited Caméras dans le combat. This initiative not only honored Vautier and Le Garrec's original vision but also expanded its scope to include feminist cinema and contemporary militant images. By bringing together these diverse works, the program underscored the enduring importance of international solidarity in the realm of militant filmmaking.https://opencitylondon.com/events/non-aligned-film-archives-09-cameras-dans-le-combat-rene-vautier-et-nicole-le-garrec/

1. Kimbe red pa moli ! — a Guadeloupean Creole expression meaning “Hold on, don’t give up!” — is an animated film.

Directed by Jean-Denis Bonan, in close collaboration with Mireille Abramovici and Caroline Biri (Sewteland pseudo), Kimbe red pa moli! bridges the struggles of post-1968 France and the 1970 sugarcane workers’ strike in Guadeloupe. Produced within the orbit of the Atelier de recherches cinématographiques (ARC) and later Cinélutte, the film embodies the political and aesthetic experiments of the French militant cinema of the 1970s.

Unable to travel to Guadeloupe for lack of funds, the filmmakers turned to animation ; clay figurines and cardboard sets, to reimagine a distant workers’ struggle.

2. Groupe d’Organisation Nationale de la Guadeloupe (GONG). The first Guadeloupean nationalist organization was founded in Paris in June 1963, at the initiative of a generation of students who had developed their nationalist education within the AGEG (Association Générale des Étudiants Guadeloupéens) and in the international anti-imperialist student movement, then within the Front antillo-guyanais pour l’autodétermination (1960–1961). The GONG emerged as a typical national liberation political organization of the 1960s: essentially Third-Worldist in its initial inspiration, it was also significantly influenced by the Algerian Revolution and Maoist ideology.

(Translation of a note by Jean-Pierre Sainton, pp. 16–17, in Elsa Dorlin, Guadeloupe Mai 67. Massacrer et laisser mourir, Libertalia, 2023.)

3. Jacques Nestor (1941–1967) was a fisherman and nationalist activist, a member of the Pointe-à-Pitre group of the Gong. An active militant deeply involved in grassroots action, Nestor participated in all of the Gong’s agitation and propaganda activities between 1965 and 1967, and became well known to the police. A quintessential mass leader, he stood at the forefront of the demonstrations on May 26, 1967, where he was targeted and fatally shot at the very beginning of the clashes. News of his death played a major role in sparking the uprising among young people from working-class neighborhoods, where he was well known and widely respected.

(Translation of a note by Jean-Pierre Sainton, pp. 16–17, in Elsa Dorlin, Guadeloupe Mai 67. Massacrer et laisser mourir, Libertalia, 2023.)

4. In 2024, researcher and curator Léa Morin and I presented one of our Non-Aligned Film Archives programs at Open City London, which revisited Caméras dans le combat. This initiative not only honored Vautier and Le Garrec's original vision but also expanded its scope to include feminist cinema and contemporary militant images. By bringing together these diverse works, the program underscored the enduring importance of international solidarity in the realm of militant filmmaking.https://opencitylondon.com/events/non-aligned-film-archives-09-cameras-dans-le-combat-rene-vautier-et-nicole-le-garrec/

Annabelle Aventurin

Annabelle Aventurin is film archivist and responsible for the preservation and distribution of Med Hondo’s archives at Ciné-Archives in Paris. In 2021 she coordinated, with the Harvard Film Archive, the restoration of Hondo’s films West Indies (1979), and Sarraounia (1986). She is also a film programmer. In 2022, she completed her first documentary film, Le Roi n'est pas mon cousin (30 min, France/Guadeloupe) screened at Cinéma du Réel, Third Horizon Film Festival (Miami), Rencontres internationales du documentaire de Montréal and in France, Martinique and French Guiana.

︎ ︎

Annabelle Aventurin is film archivist and responsible for the preservation and distribution of Med Hondo’s archives at Ciné-Archives in Paris. In 2021 she coordinated, with the Harvard Film Archive, the restoration of Hondo’s films West Indies (1979), and Sarraounia (1986). She is also a film programmer. In 2022, she completed her first documentary film, Le Roi n'est pas mon cousin (30 min, France/Guadeloupe) screened at Cinéma du Réel, Third Horizon Film Festival (Miami), Rencontres internationales du documentaire de Montréal and in France, Martinique and French Guiana.

︎ ︎