Sorcha Thompson

Archives of Tricontinental Solidarity and Ecology

in Cuba and Beyond

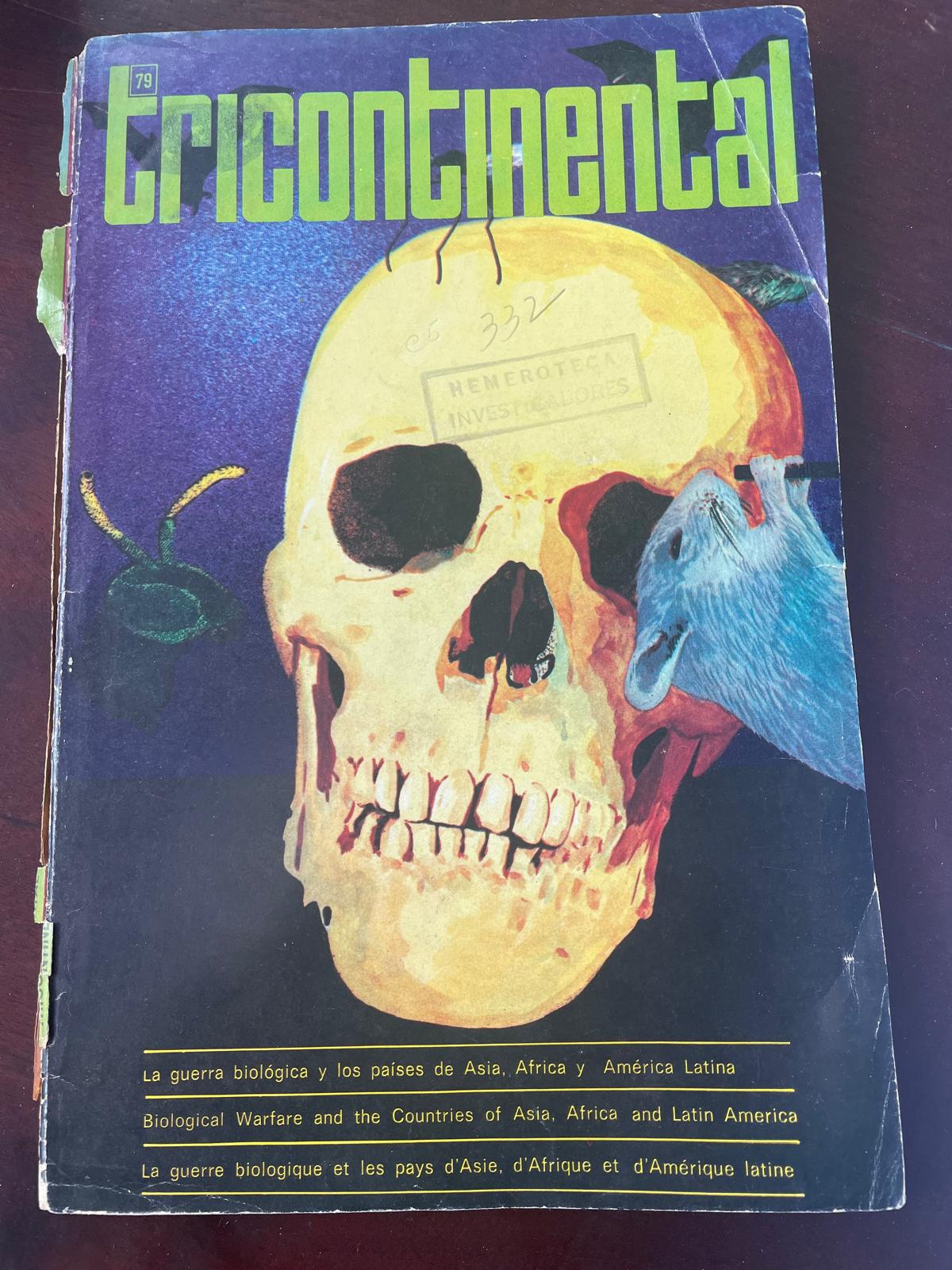

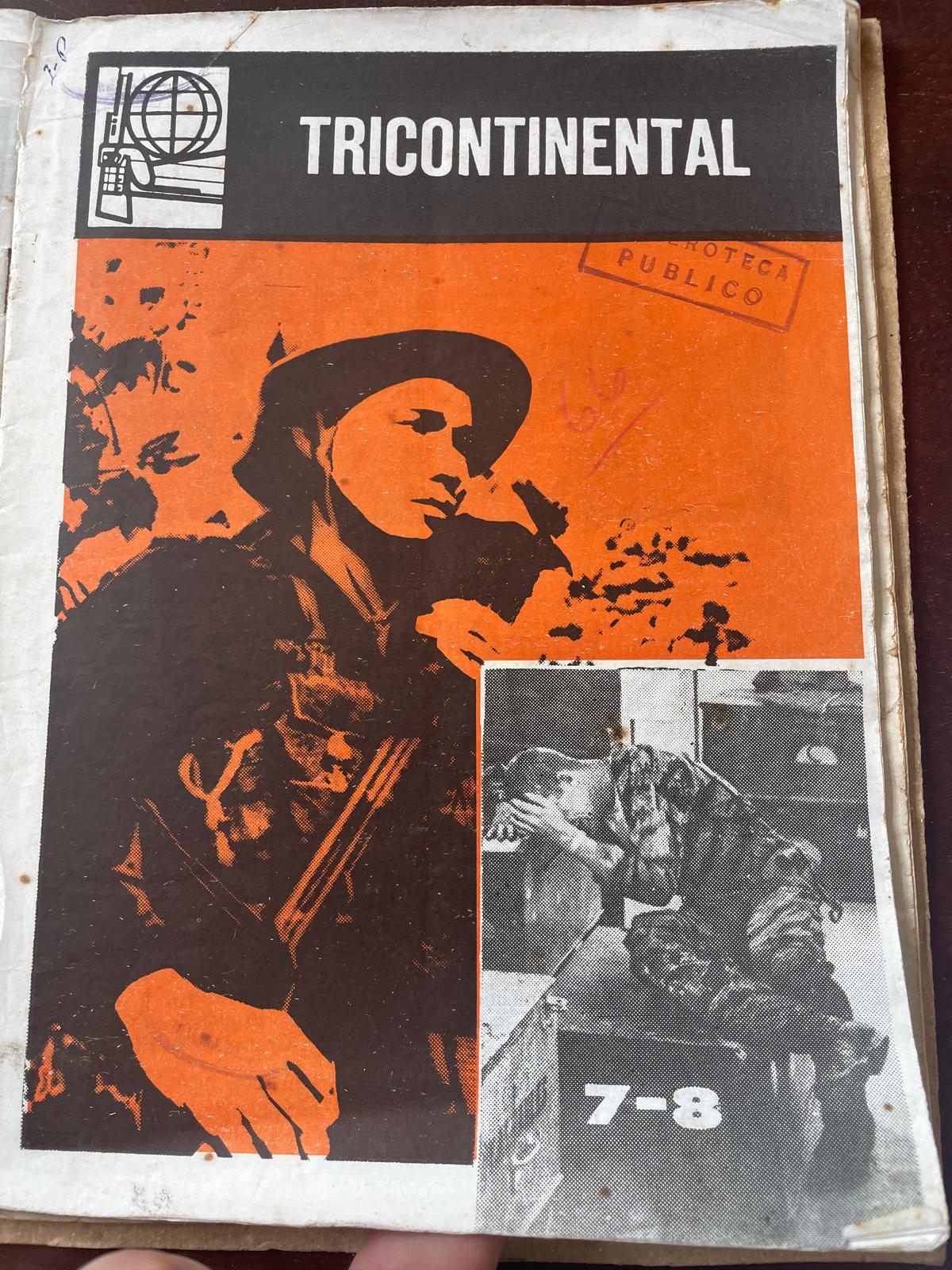

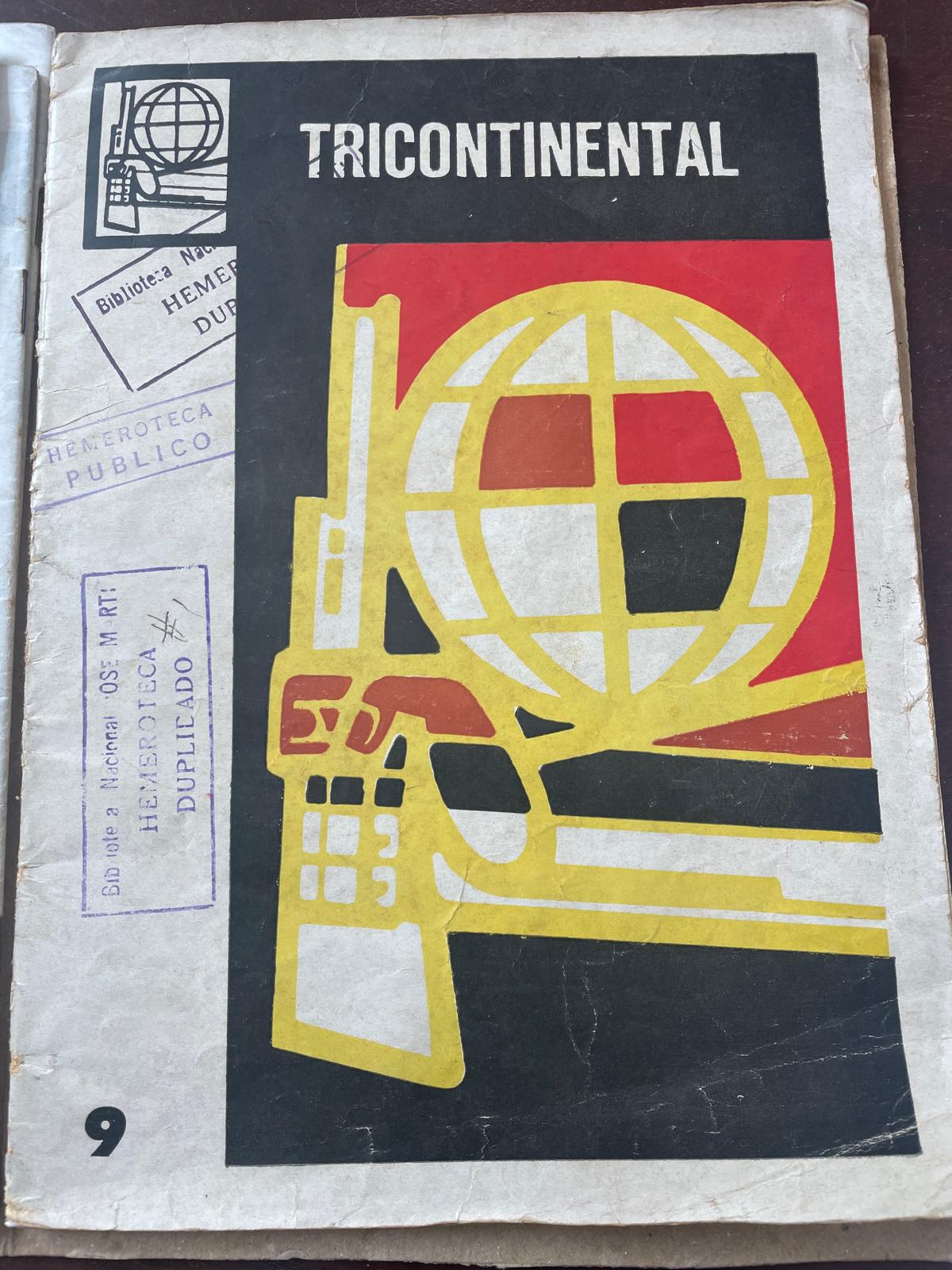

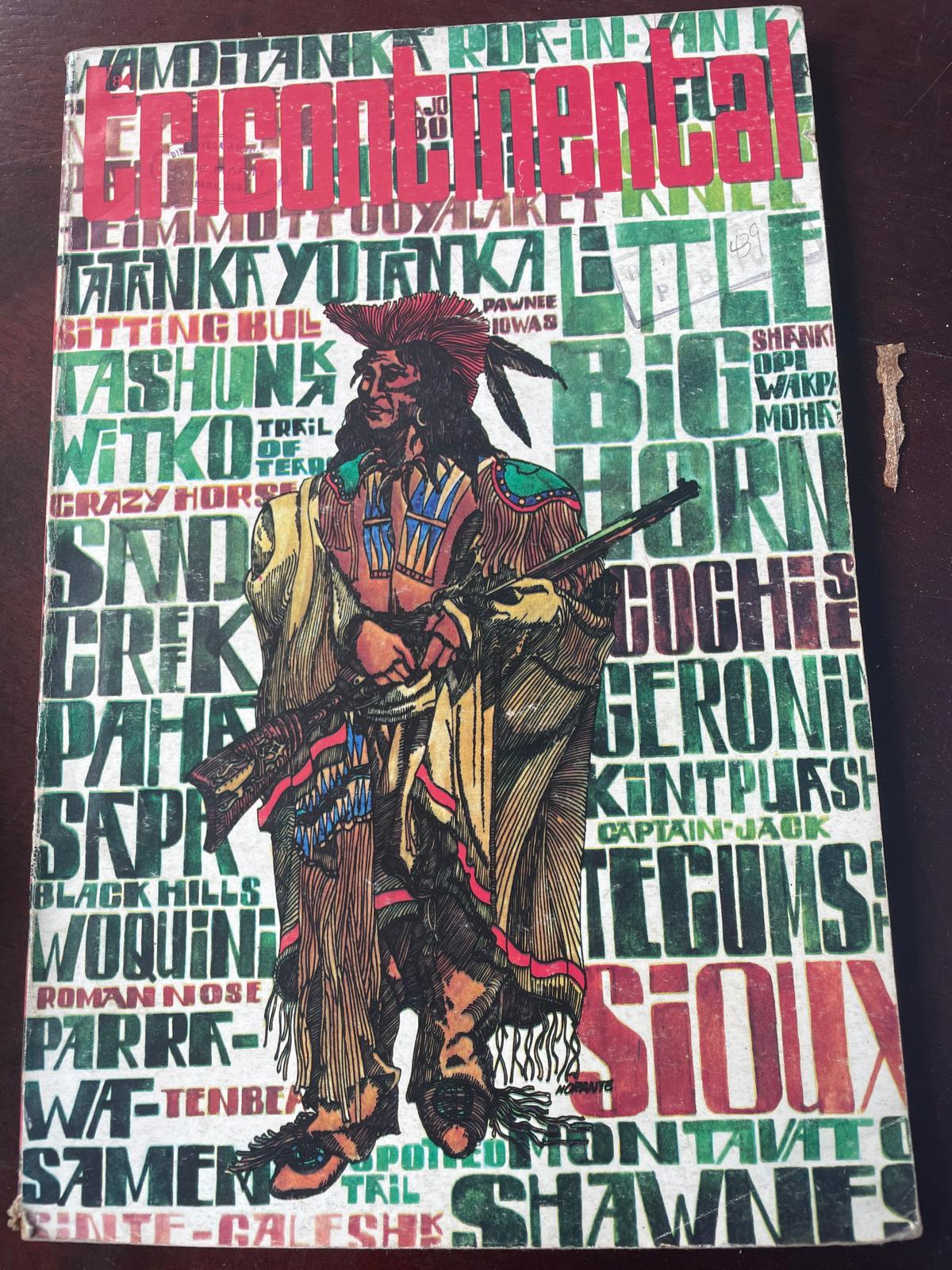

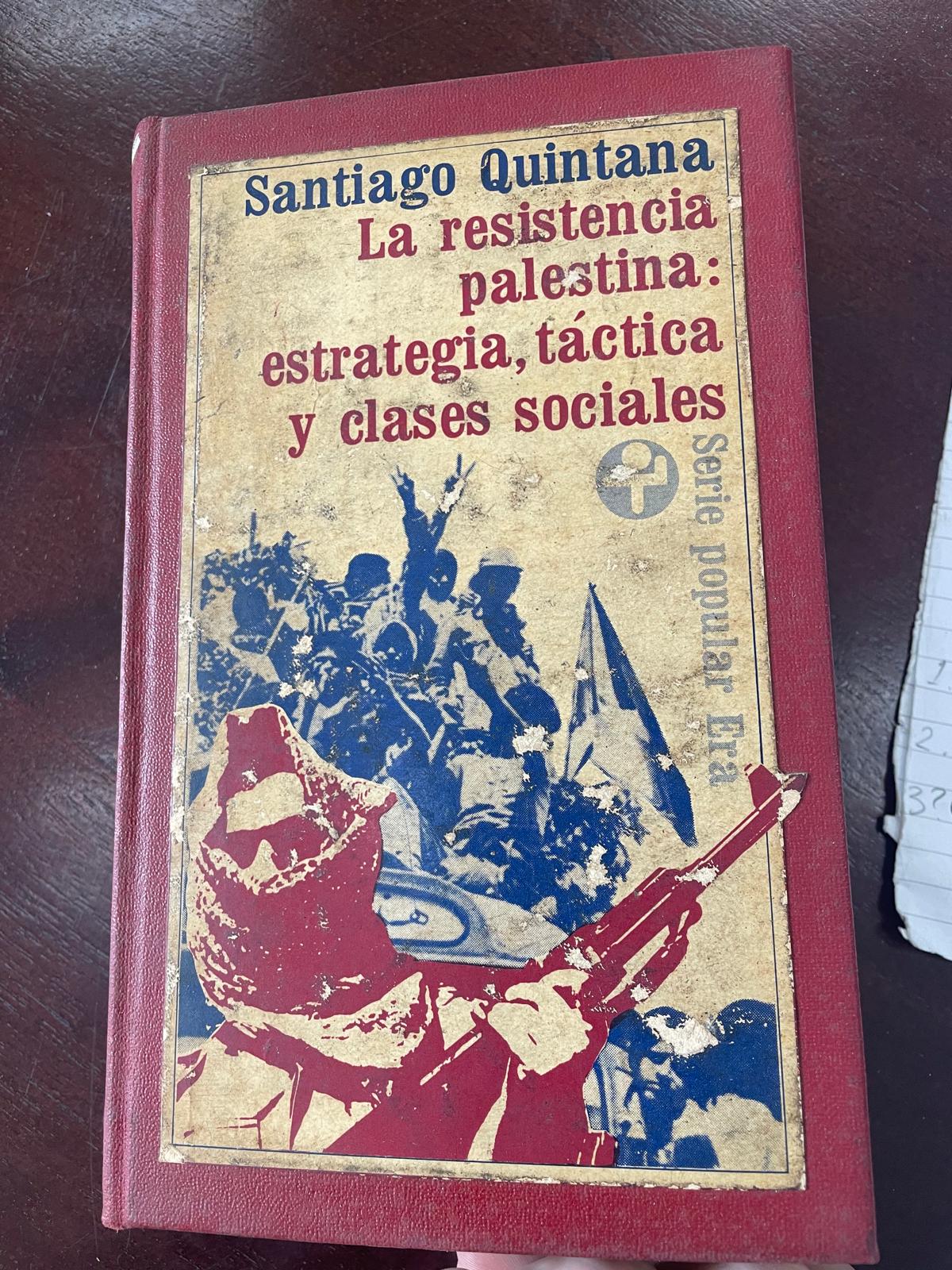

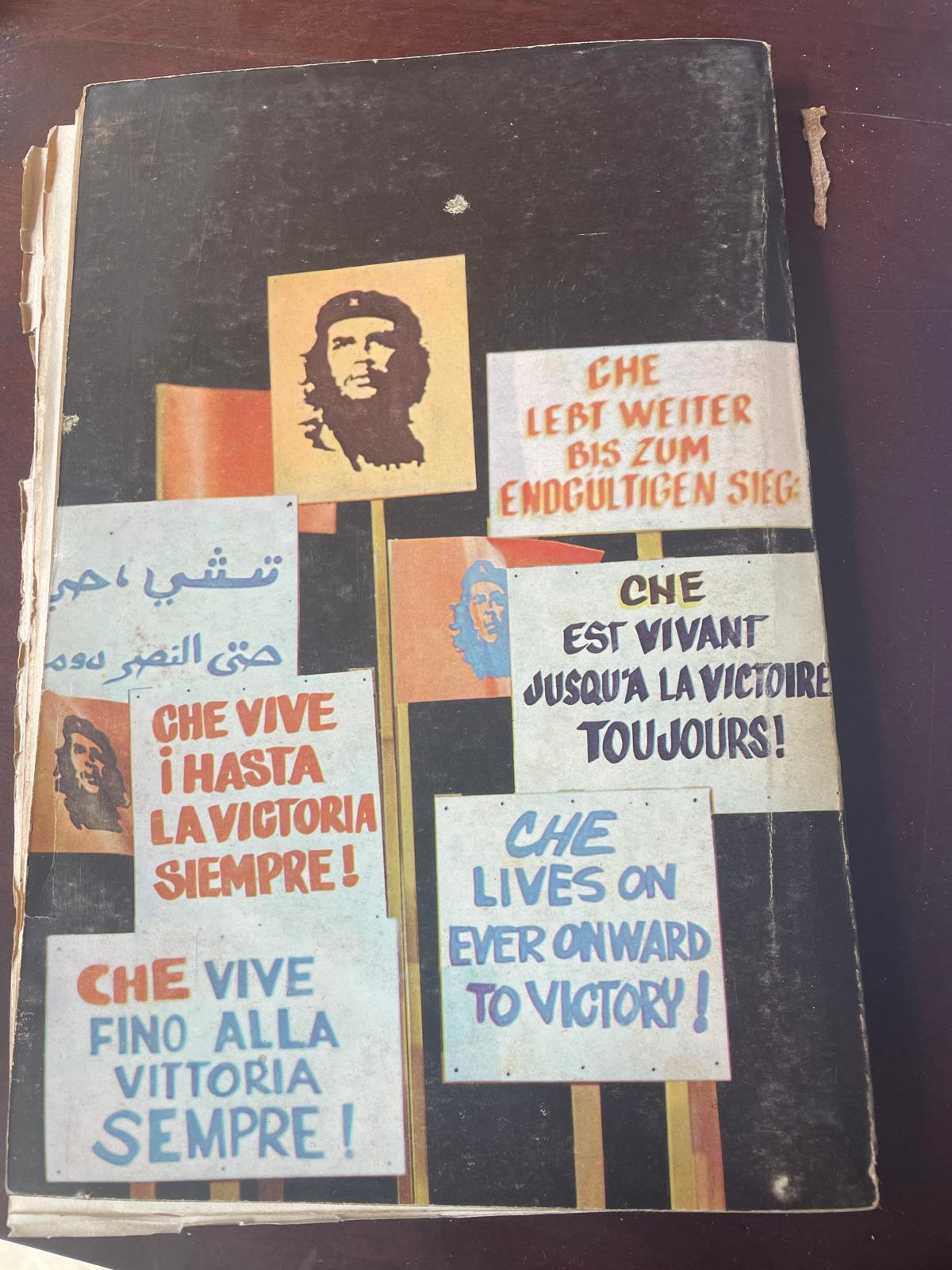

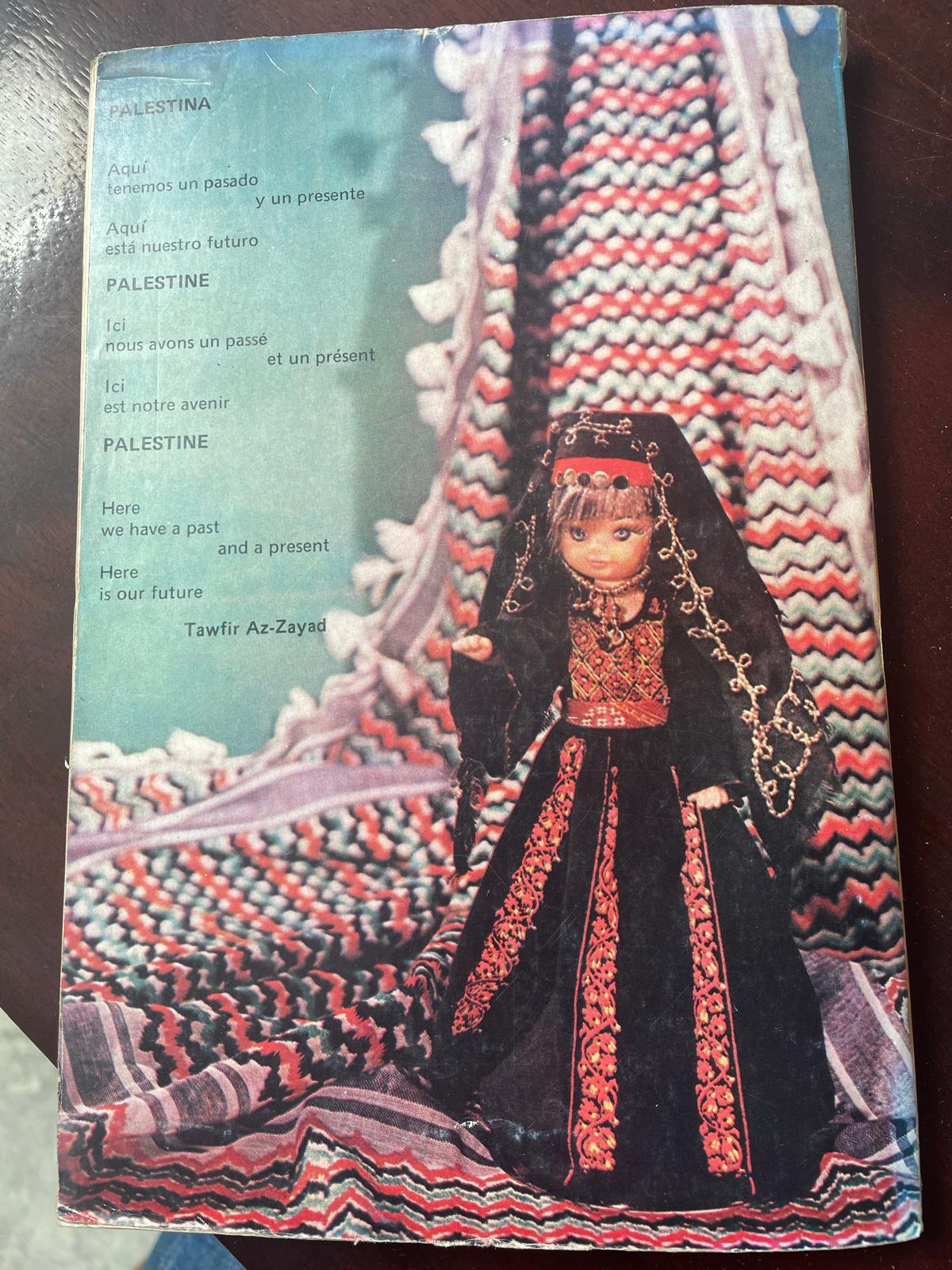

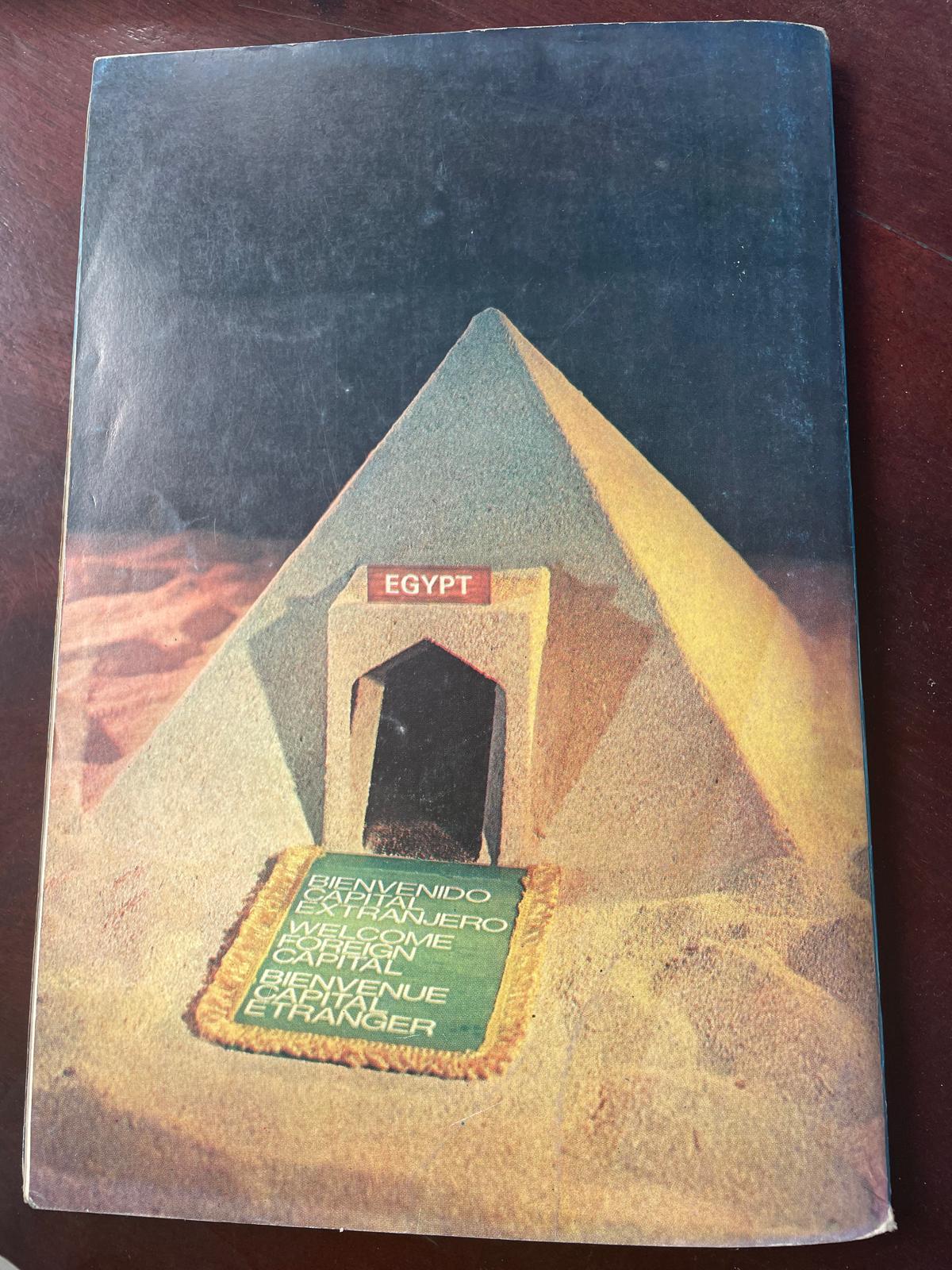

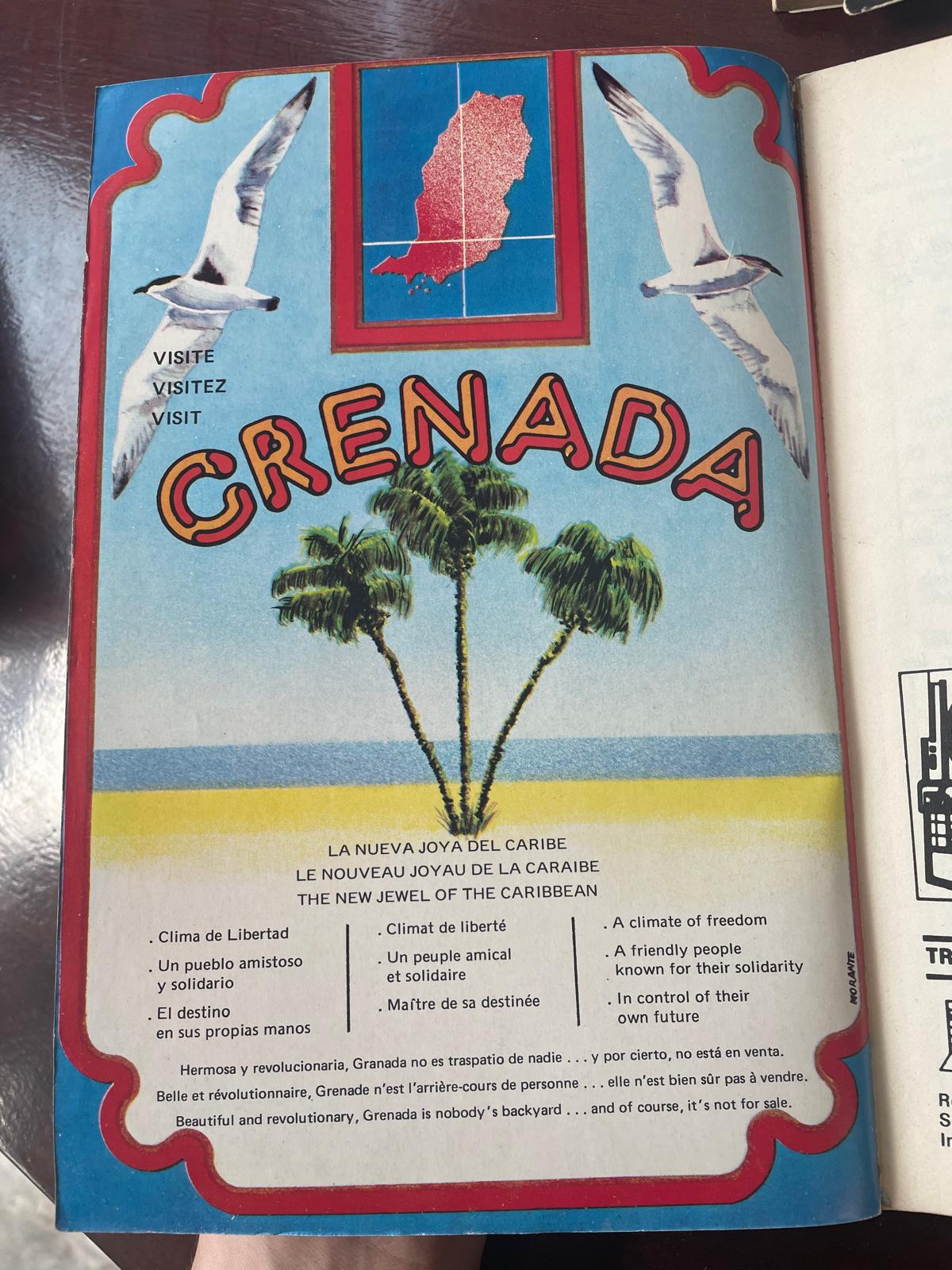

Like many before me, my initial encounters with tricontinentalism were through the cultural production of the Organisation of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America (OSPAAAL). In my doctoral research, the Tricontinental magazine was the first place I turned in order to begin tracing histories of international solidarity with Palestine in the 1960s and 1970s. On those pages, the bold graphics, the militant satire, and the evocative poster art brought to life a world of solidarity coloured by revolutionary optimism, interconnected struggle and transformative possibility.

It was a world that in many ways seemed far away from the time and place in which I stood. From a library in Britain in the late 2010s, in a moment when solidarity with Palestine, anti-imperial politics and political imagination faced renewed attack, it was inspiring to turn to these pages where parallel movements for liberation were invited to narrate their own histories and assert a radical visibility.

Since then, the aesthetics of the Tricontinental movement have become increasingly visible to new audiences, with multiple exhibitions of OSPAAAL material in universities, museums and art institutions across the world. And with an expanding body of scholarly work, our knowledge of tricontinentalism has grown. Once a term primarily associated with the 1966 Tricontinental Conference hosted in Havana (itself painted in somewhat simplified terms as the more militant follow up to 1955 Bandung Conference that brought Latin America into the Afro-Asian sphere), tricontinentalism has now become recognised more broadly as a distinctive ideology and form of twentieth century anti-imperialism.

This tricontinentalism contained a vision of solidarity and resistance grounded in the liberation struggles of Africa, Asia and Latin America that extended to include movements of the ‘exploited of the world’ within the imperial core. It was distinguished by its attempt to pioneer a new Third Worldism, one that openly supported ongoing anticolonial movements and that envisaged a version of global socialism distinct from the models emanating from both the Socialist Bloc and Western Europe. My work - which has involved navigating and connecting archival traces of tricontinental solidarity movements across continents - has concentrated on understanding such tricontinentalism as a praxis, in a way that centres the people who forged and practiced its ideas, and their impacts on the world around them in doing so.

It was a world that in many ways seemed far away from the time and place in which I stood. From a library in Britain in the late 2010s, in a moment when solidarity with Palestine, anti-imperial politics and political imagination faced renewed attack, it was inspiring to turn to these pages where parallel movements for liberation were invited to narrate their own histories and assert a radical visibility.

Since then, the aesthetics of the Tricontinental movement have become increasingly visible to new audiences, with multiple exhibitions of OSPAAAL material in universities, museums and art institutions across the world. And with an expanding body of scholarly work, our knowledge of tricontinentalism has grown. Once a term primarily associated with the 1966 Tricontinental Conference hosted in Havana (itself painted in somewhat simplified terms as the more militant follow up to 1955 Bandung Conference that brought Latin America into the Afro-Asian sphere), tricontinentalism has now become recognised more broadly as a distinctive ideology and form of twentieth century anti-imperialism.

This tricontinentalism contained a vision of solidarity and resistance grounded in the liberation struggles of Africa, Asia and Latin America that extended to include movements of the ‘exploited of the world’ within the imperial core. It was distinguished by its attempt to pioneer a new Third Worldism, one that openly supported ongoing anticolonial movements and that envisaged a version of global socialism distinct from the models emanating from both the Socialist Bloc and Western Europe. My work - which has involved navigating and connecting archival traces of tricontinental solidarity movements across continents - has concentrated on understanding such tricontinentalism as a praxis, in a way that centres the people who forged and practiced its ideas, and their impacts on the world around them in doing so.

Archives of Tricontinental Solidarity in Cuba

Where, then, can one then go to access the archive of tricontinentalism as praxis, as something made by people and embedded in political struggle? One potential starting point, and the place I continued my research journey, is Havana, the host city of the 1966 Tricontinental Conference and the subsequent base of OSPAAAL. Cuba was a meeting place, a base and a gateway for liberation movements and revolutionary parties from across the tricontinental world, whose own paper trails and archival traces have been left on the island.

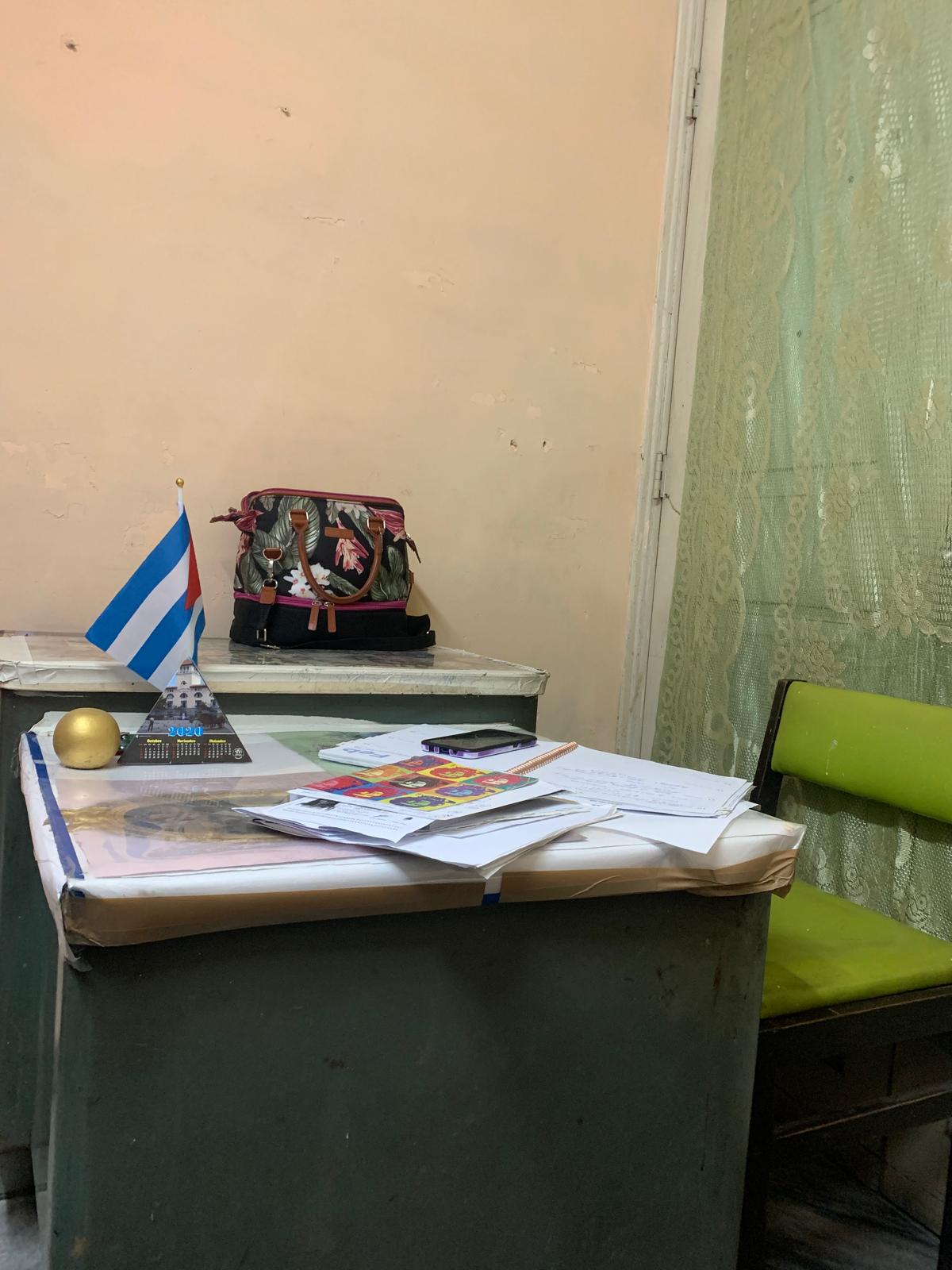

Moving through Havana, one passes the many institutions that have been pillars in the state’s infrastructure of tricontinental solidarity before and since the 1966 Conference - the buildings of the Institute of Friendship with the Peoples (ICAP), the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), the Federation of University Students (FEU), Casa de las Americas, the closed offices of OSPAAAL itself, or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MINREX). These institutions had different priorities and approaches to building and consolidating tricontinental solidarity, and can be entry points to the overlapping networks of tricontinental praxis. At the same time, they all exist in varying degrees of precarity. The closure of the OSPAAAL office in 2019 meant the relocation of its archival material to other institutions inside Cuba and abroad, a process that is still underway. The library of the Institute of History has been partially closed as the building undergoes much needed and delayed repairs. The archives of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) - which contain a wealth of film produced in collaboration with and about tricontinental movements - also faces critical challenges to maintain the condition of its collection, including the impact of intermittent electricity blackouts. The conditions in which these collections exist and the challenges they face are part of the reality of archiving under blockade.

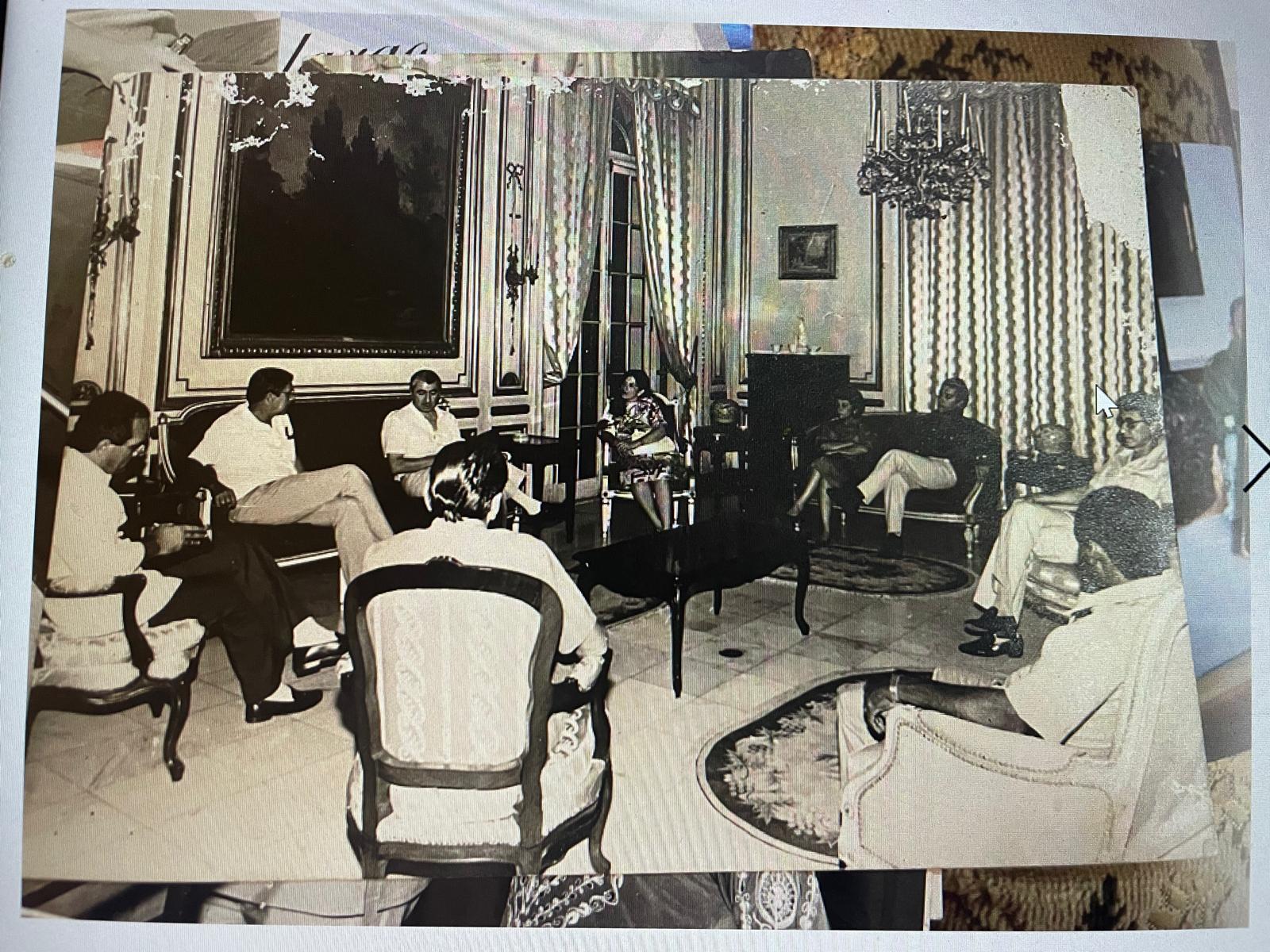

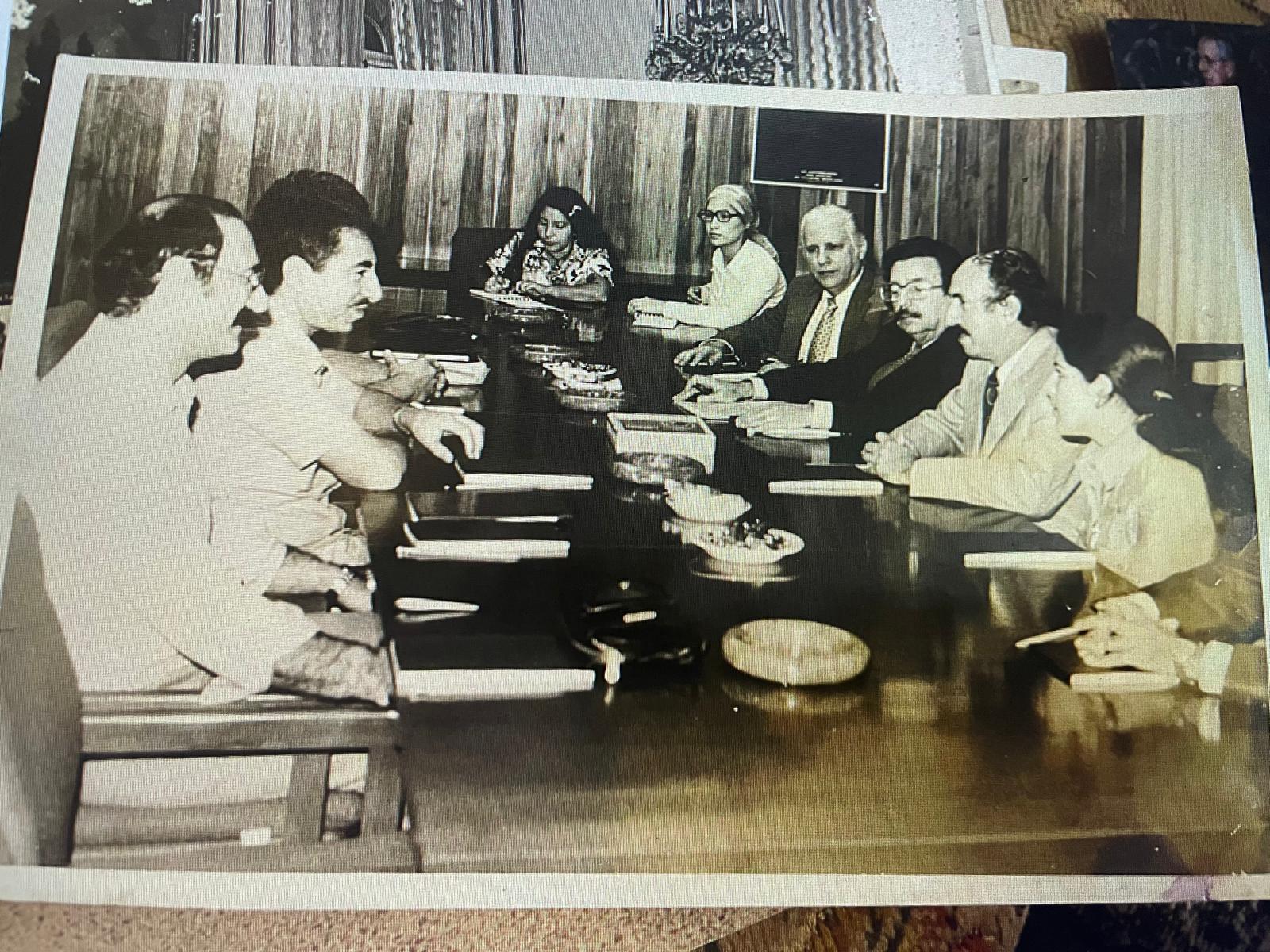

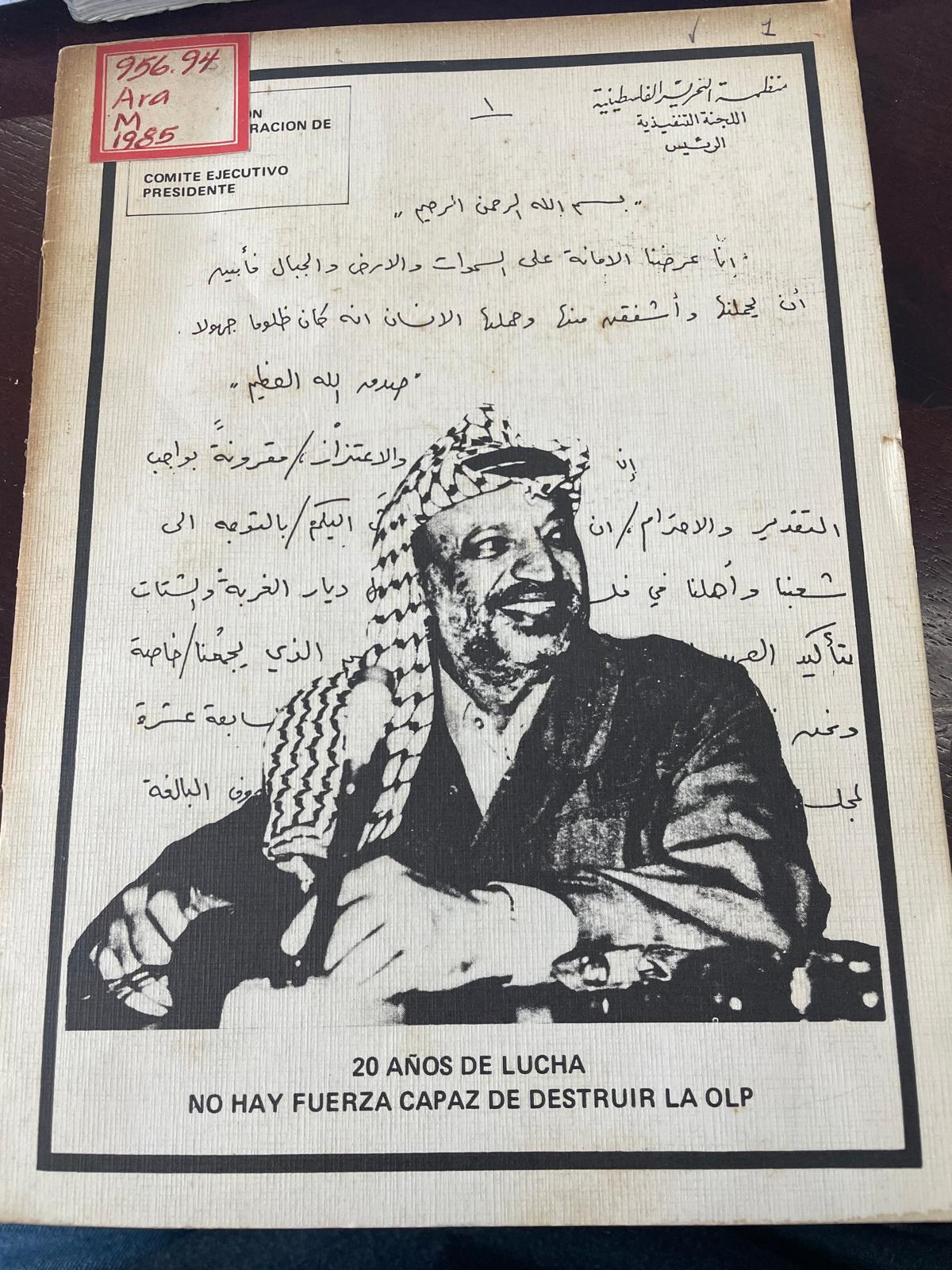

One Cuban state archive that is potentially and partially open to researchers is the archive of the Ministry of Foreign Relations (MINREX), containing documents related to Cuba’s bilateral international relations. For me, visiting the MINREX archives brought insight to the praxis of tricontinentalism as a political project across multiple geographies. In the paper trails of meetings that moved through Havana, Pyongyang, Hanoi, Beirut, and Aden, I could trace how leaders of liberation movements and Cuban officials met to discuss, debate and strategically shape the anti-imperial positions that they would then take to international institutions, in a demonstration of South-South solidarities and Third Worldist diplomatic agency that cut through the dividing logic of the ‘global Cold War.’ I also saw evidence of the attempts to extinguish these networks, with blurred communiques revealing the circulation of imperialist plans to topple governments and crush popular movements in Haiti, Lebanon, Palestine and Cuba, through the spread of misinformation and the mobilisation of counter-revolutionary forces. Such archival fragments, typically raising more questions than answers, were a reminder of the existential threat that the political project of tricontinentalism was deemed to pose to the imperialists and their global vision.

But we know that the vast archive of tricontinental history is not primarily held in official buildings or documented on letter-headed papers. The people who I met in Havana had their own stories to tell and their own records of participating in the networks of tricontinental solidarity - which include the thousands of Palestinians who have pursued education and training in various fields in Cuba, and the Cubans who went on scholarships to learn in the Middle East. One of these people was Maria*, who at the age of 18 went to study Arabic in Damascus. She came back to Cuba to assist in the 1978 World Festival of Youth and Students in Havana, where she accompanied the Sudanese youth delegation as a guide. She later went on to become an Arabic-Spanish translator, travelling with Cuban officials to the Middle East and North Africa and working with visiting delegations in Cuba. Alongside her rich oral history, her personal archive consists of a photography collection, as well as physical objects - such as the t-shirts and badges distributed at youth and student festivals, and gifts received by the many visitors and friends she has hosted over the years.

But we know that the vast archive of tricontinental history is not primarily held in official buildings or documented on letter-headed papers. The people who I met in Havana had their own stories to tell and their own records of participating in the networks of tricontinental solidarity - which include the thousands of Palestinians who have pursued education and training in various fields in Cuba, and the Cubans who went on scholarships to learn in the Middle East. One of these people was Maria*, who at the age of 18 went to study Arabic in Damascus. She came back to Cuba to assist in the 1978 World Festival of Youth and Students in Havana, where she accompanied the Sudanese youth delegation as a guide. She later went on to become an Arabic-Spanish translator, travelling with Cuban officials to the Middle East and North Africa and working with visiting delegations in Cuba. Alongside her rich oral history, her personal archive consists of a photography collection, as well as physical objects - such as the t-shirts and badges distributed at youth and student festivals, and gifts received by the many visitors and friends she has hosted over the years.

Entangled Archives of Tricontinentalism

For those looking to understand the meaning and organisation of a world of solidarity that shaped a high age of anti-colonialism, such oral histories and personal archives can be an avenue into the more granular, interpersonal and reflexive layers of tricontinentalism. But as Karma Nabulsi and Abed Takriti have noted, one of the challenges of retrieving such histories is the rhetoric dissonance that exists between the political languages and revolutionary practices of that era and the contemporary age, which can make it both difficult for cadres of an earlier generation to articulate the reality of their lived collective experiences, and for today’s generation of activists to engage with and make sense of their world.

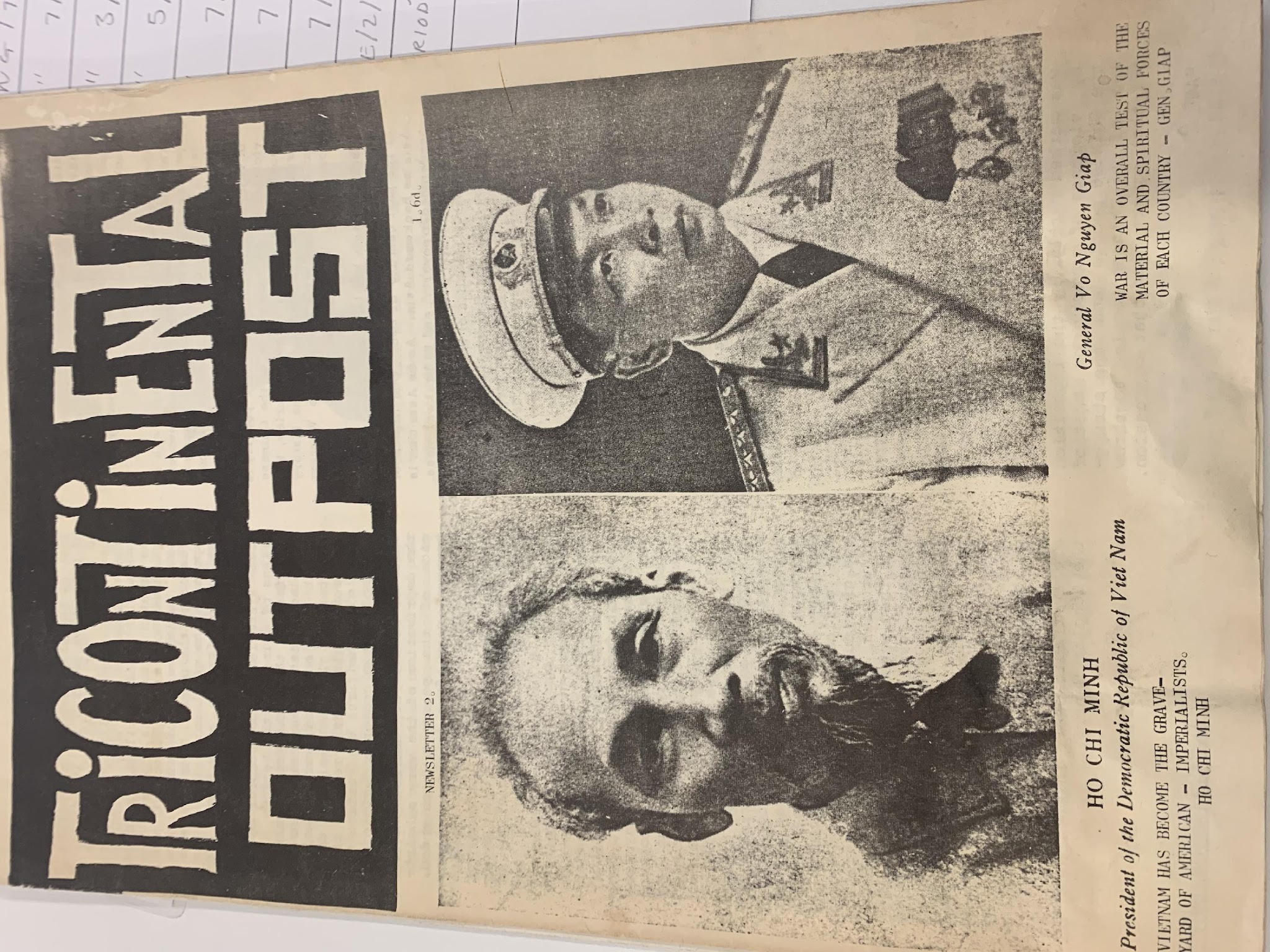

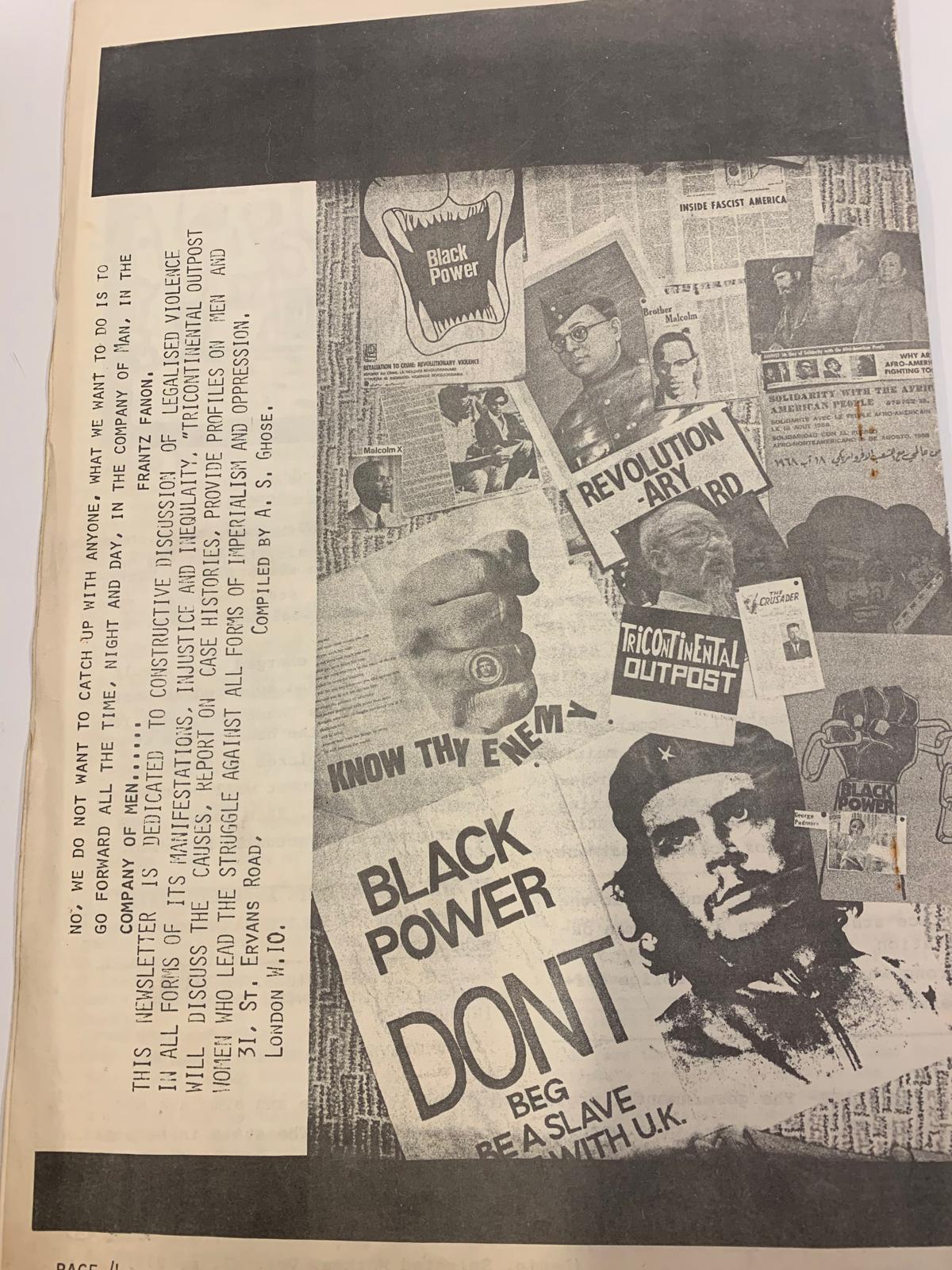

Perhaps it was an aspect of this dissonance that I also experienced when reading the Tricontinental magazine for the first time, its pages a portal into a ‘seemingly distant galaxy of revolutionary national liberation movements’. The attack on anti-imperial politics and solidarity in Britain has always been connected to the struggle over history; attempts to impose and maintain an imperial amnesia work to not only distort Britain’s place in the world, but to rupture contemporary political struggles from the connected traditions of anticolonial resistance from which they derive. Amongst these histories, much remains deeply buried. There was, for example, a now little-known Tricontinental Outpost based in London’s Notting Hill, describing itself as a “passionate revolutionary mouthpiece” of “the local and international struggle for freedom in all its forms.”

Resisting the reduction of tricontinentalism into a geographically-bounded concept, a distant historical artefact or an aesthetics of mere curiosity, my work has pursued a multi-site and multi-layered archival approach centred on engaging with the revolutionaries and activists who organised and built such solidarities across continents and the conditions in which they did so. Reading tricontinental magazines as part of an entangled and living archive of political praxis can connect such forms of cultural production with the plural remits, strategies and political imaginations of past activists that might then speak across generations.

Tricontinental Imprints

With this in mind, there remains much to learn from the tricontinental era. Amongst the emergent retrievals of this past are those that highlight the latent (and at times explicit) socio-environmental dimensions that can be read in the Tricontinental magazine, illustrating how ecological concerns subtly underpin its anti-imperialist and internationalist content. Inspired by these readings, and by the enduring centrality of land questions to liberation movements, my ongoing research starts from the position that while the Tricontinental was a project rather than a place, tricontinentalism has also had a distinctive planetary imprint.

Tricontinental praxis spawned extensive networks of dialogue, exchange and practical cooperation on shared questions of land redistribution and use, resource extraction and management, and political and ecological sovereignty, much of which preempted later emerging eco-socialist arguments. Turning our lens to the environmental histories of tricontinentalism might allow for a reconsideration of the solidarities of the ‘exploited of the world’ that it sought to galvanise – of their potentialities between peoples and with the rest of the natural world – in a way that speaks to today’s urgent planetary prerogatives.

A next step in my research, as part of the Socialist Anthropocene in the Visual Arts (SAVA) project, turns to a site marked by the planetary imprint of tricontinentalism: the Isla de Juventud (Island of Youth). Sitting 50km to the south of the Cuban mainland, it is an island that has inspired many names and uses in its history of human encounter, from a home of the indigenous Siboney people and a landing point of Christopher Colombus in 1494, to hosting the Hilton Hotels of the US Empire and the prisons of the Fulgencio Batista regime in the 1950s. In 1967, Fidel Castro set out the plan that socialist Cuba had for la Isla, in a speech at the inauguration ceremony of its ‘Viet Nam Heroico’ dam:

“Here the youth must give themselves to the task of revolutionising nature…. Why not aspire to turn this region into the first communist region of Cuba? Let us propose not only to revolutionise nature, but also to revolutionise minds, to revolutionise society, since here there are the objective conditions to make this feasible.”

From Castro's 1967 speech until the 1990s, tens of thousands of young Cubans and students from Africa, Asia, the Americas and Europe went to the island to live, study, work, farm and build, with many specialising in citrus studies, hydraulics, animal husbandry, engineering, and soil science. Tracing the trajectories of these people through entangled archives is one way we might explore the manifestations of an “ecopolitical unconsciousness” amongst the tricontinental generation. At the same time, thinking with planetary imprints asks us to critique the idea of the “virgin” island as a "field of action” for geotransformación, and to consider how the land’s entanglements with socialism differed from and interacted with those from the political projects that came before. Centering the physical environment within our archival practice requires us to fix our historical imaginations to the deep planetary networks of which such sites and people are part, through which tricontinental imprints can be traced between and beyond seemingly distant island shores.

Sorcha Thompson

Sorcha is an interdisciplinary historian of twentieth century anticolonial and socialist movements. She is particularly interested in the role of tricontinental movements and their solidarity networks in shaping global political agendas and imaginations. In 2024 she was awarded her PhD in the social sciences from Roskilde University, where her project analysed the Palestinian liberation movement’s solidarity networks between 1948 and 1982, from the state support of socialist Cuba to the activism of new left groups in Britain.

︎ ︎

Sorcha is an interdisciplinary historian of twentieth century anticolonial and socialist movements. She is particularly interested in the role of tricontinental movements and their solidarity networks in shaping global political agendas and imaginations. In 2024 she was awarded her PhD in the social sciences from Roskilde University, where her project analysed the Palestinian liberation movement’s solidarity networks between 1948 and 1982, from the state support of socialist Cuba to the activism of new left groups in Britain.

︎ ︎