Nivi Manchanda

Basque-Palestinian Solidarity

In the face of the unremitting horror of a ‘fast’ genocide in Palestine (in contrast to the slow one that’s been enacted over decades), the desire to cling on to hope is both at its most intense, and its most brittle. Nothing is quite up to the task - I’m not sure what that means and could even look like in the present moment – but invocations and demonstrations of solidarity provide some respite. The most visceral and extensive displays of solidarity with Palestine that I have observed over the last year were those that adorned the Basque Country (Euskal Herria), officially part of the Spanish state. Unofficially, a cauldron of resistance, left-wing activism, and a space of politics that Spain both tries to constrain and contain, with mixed success.

1.

Basque Country is an appellation denoting the geographical area located on the shores of the Bay of Biscay and on the two sides of the western Pyrenees that straddles the border between France and Spain. The region consists of three different political structures: the Basque autonomous community, also known as Euskadi; Navarre in Spain; and the three Northern Basque historical provinces (Labourd, Lower Navarre and Soule), administratively part of the French department of Pyrénées-Atlantiques. The many groups agitating for Basque self-determination have differing demands that occasionally but not always include a unified Basque nation. For more on this see: Full article: The Importance of Historical Context: A New Discourse on the Nation in Basque Nationalism?

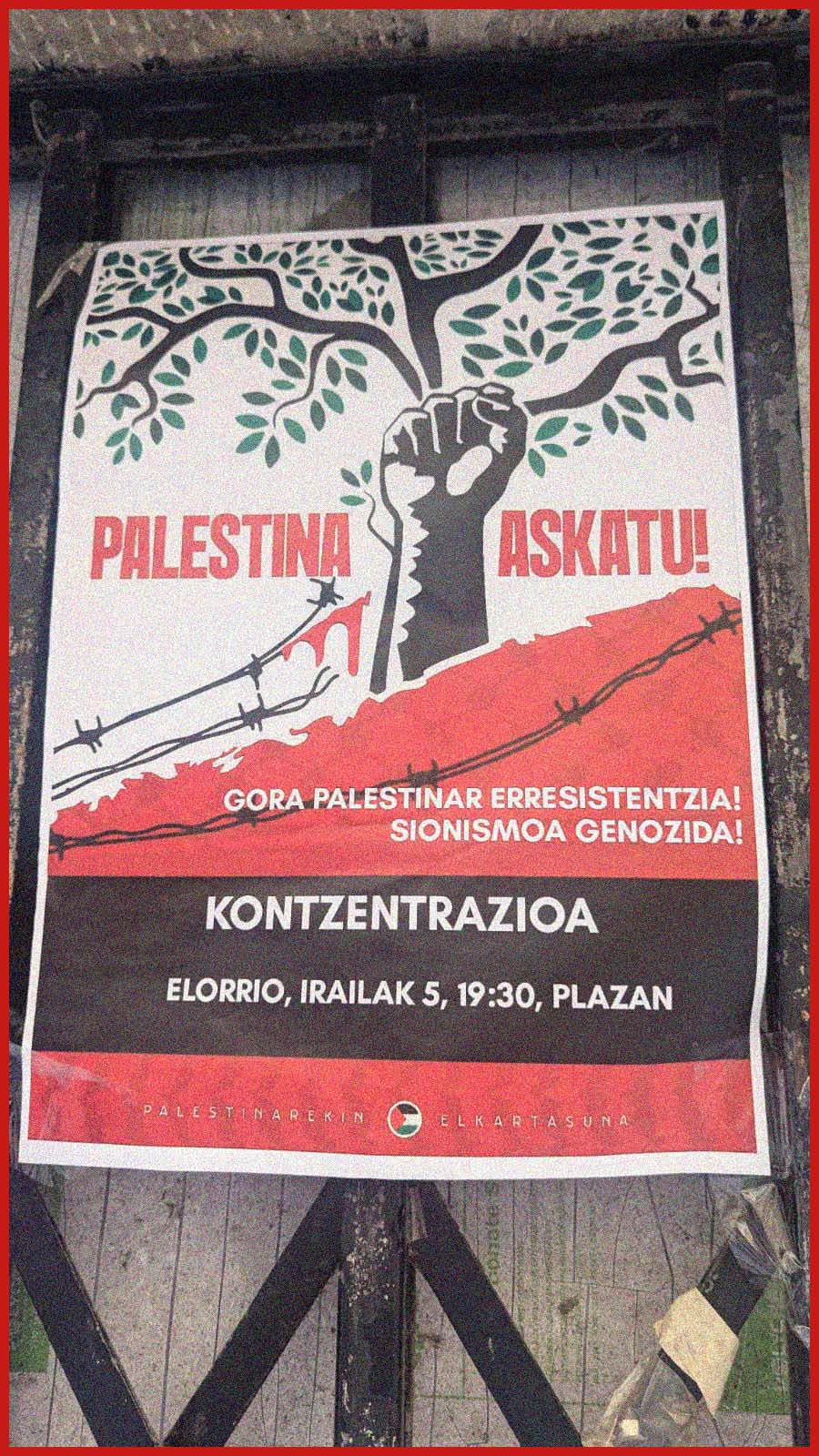

Over the summer my partner and I cycled from Caen in France all the way to Bilbao on a tandem (full disclosure: I was the free-rider/deadweight). As the glitzy Biarritz scenery slowly gave way to the industrial hues of Oridizia, the change was palpable in more ways than one. The bordertown of Ordizia, (formerly known as Villafranca de Ordizia) is part of the Goierri region of the province of Gipuzkoa, in the autonomous community of the Basque Country.1 Ordizia was immediately distinctive: there were no touristy pretensions, no hipster cafes, and no ‘artisanal’ bakeries. It was instead festooned with Palestine flags, Free Palestine posters, and various homemade stickers in Basque that praised the resistance, called for a boycott of Israel, or compared the Palestine fight for independence with the Basque struggle. Shopfronts were bedecked with these flags, most houses had one hanging on their windows, the graffiti and stickers were everywhere. One did not need an archivists’ or indeed even a historian’s sensibility to be able to discern and want to document, an incredibly staunch commitment to a cause that should be universal, but has always been siloed, ghettoised, and ‘de-normalised’. This was not the first time that Palestinian cries for justice reverberated in their full resounding urgency, halfway across the world, but in the present historico-political moment, the unwavering support of a small European town felt brave and poignant, and strangely enough, a bit of a relief.

![]()

![]()

![]()

For context: the Basque struggle for autonomy officially began in the 19th Century, although it is most closely (and recently) associated with the formation of the Euskadi Ta Askatasuna in 1959. The ETA which stands for Basque Homeland and Liberty was a left-wing, specifically Marxist-Leninist, separatist organisation inspired by anti-colonial movements in the Third World including in Cuba and Vietnam. The brutal repression and torture by Franco’s regime of Basque nationalists led to an embrace of armed self-defence and violence by the ETA. The ETA was considered a “terrorist organisation” by the Spanish state, support for it waned after the Basque Country was given autonomous status in 1979, and it was disbanded in 2018. There are a host of other Basque independence movements and organisations that remain active but none espouse violence as their means.

Ordizia, and as I discovered in the days that followed, Ellorio, San Sebastian, and Bilbao all stood with Palestine. They did not merely march on weekends; they also held festivals of solidarity, refused to do business with or serve ‘Zionists’, and engaged in a cultural, political, and certainly social boycott of the Israeli state. San Sebastian, that bolthole for the rich and the glamorous, with its gorgeous coastline, its charming old town and a slew of michelin-star restaurants, is also a hotbed of unrepentant self-determination. I counted 73 Palestinian flags in a space of about 800 metres, the independent shops had ‘Boikot Israel’ stickers in their windows, the kids donned Palestine football journeys, and the babies slept soundly in their watermelon themed prams. I am aware that this sounds like a perverse idyll given the backdrop of a murderous onslaught on Palestinian people, lands, and dreams, but yet again, the knowledge that others around you were grappling with their (clearly unwitting) complicity in mundane if vibrant ways was a source of succour in the midst of the horror.

![]()

![]()

There were less banal displays of solidarity too. In December 2023, Guernica (Gernika) a small Basque city in the province of Biscay held a vigil for Palestine. Guernica is famous for its ruthless decimation by a coalition of fascists in 1937. Its history is instructive: in the midst of an already bloody civil war, and at Franco’s behest, Nazi Germany’s Condor Legion and Fascist Italy’s Aviazione Legionaria came together to massacre civilians in what is widely regarded as one of the world’s first aerial bombardments, as well as a crime against humanity. Guernica – a luftwaffe experiment in blitzkrieg tactics – then drew an explicit and heartrending parallel with Palestine. Thousands of people came together to form a mosaic of the Palestinian flag, dressed in red, green and black. They took over the main square, the Pasialeku Market Place, and urged the so-called international community to stop the genocide. Alongside the Palestinian flag they also formed part of Picasso’s evocative entitled ‘Guernica’, painted in the immediate aftermath of the bombardment of the city. Picasso has memorialised the massacre through art for many who only know of Guernica because of his painting (as I had done).

![]()

It is this very memory of fascism, that seems to have receded from much of Europe except in its artistic expression, or worse instrumentalised in a horrific irony to instead further the very fascism it seems to loudly proclaim to never forget, that Spain in general and in Basque Country in particular still keeps alive. Not in a fetishisation of the past, but in an acute awareness of its afterlives and ongoing present. It is for this reason that solidarity with the resistance in Palestine - whatever our opinion of it – is not criminalised in Spain, the way it is in the UK, the US, and in Germany.

For context: the Basque struggle for autonomy officially began in the 19th Century, although it is most closely (and recently) associated with the formation of the Euskadi Ta Askatasuna in 1959. The ETA which stands for Basque Homeland and Liberty was a left-wing, specifically Marxist-Leninist, separatist organisation inspired by anti-colonial movements in the Third World including in Cuba and Vietnam. The brutal repression and torture by Franco’s regime of Basque nationalists led to an embrace of armed self-defence and violence by the ETA. The ETA was considered a “terrorist organisation” by the Spanish state, support for it waned after the Basque Country was given autonomous status in 1979, and it was disbanded in 2018. There are a host of other Basque independence movements and organisations that remain active but none espouse violence as their means.

Ordizia, and as I discovered in the days that followed, Ellorio, San Sebastian, and Bilbao all stood with Palestine. They did not merely march on weekends; they also held festivals of solidarity, refused to do business with or serve ‘Zionists’, and engaged in a cultural, political, and certainly social boycott of the Israeli state. San Sebastian, that bolthole for the rich and the glamorous, with its gorgeous coastline, its charming old town and a slew of michelin-star restaurants, is also a hotbed of unrepentant self-determination. I counted 73 Palestinian flags in a space of about 800 metres, the independent shops had ‘Boikot Israel’ stickers in their windows, the kids donned Palestine football journeys, and the babies slept soundly in their watermelon themed prams. I am aware that this sounds like a perverse idyll given the backdrop of a murderous onslaught on Palestinian people, lands, and dreams, but yet again, the knowledge that others around you were grappling with their (clearly unwitting) complicity in mundane if vibrant ways was a source of succour in the midst of the horror.

There were less banal displays of solidarity too. In December 2023, Guernica (Gernika) a small Basque city in the province of Biscay held a vigil for Palestine. Guernica is famous for its ruthless decimation by a coalition of fascists in 1937. Its history is instructive: in the midst of an already bloody civil war, and at Franco’s behest, Nazi Germany’s Condor Legion and Fascist Italy’s Aviazione Legionaria came together to massacre civilians in what is widely regarded as one of the world’s first aerial bombardments, as well as a crime against humanity. Guernica – a luftwaffe experiment in blitzkrieg tactics – then drew an explicit and heartrending parallel with Palestine. Thousands of people came together to form a mosaic of the Palestinian flag, dressed in red, green and black. They took over the main square, the Pasialeku Market Place, and urged the so-called international community to stop the genocide. Alongside the Palestinian flag they also formed part of Picasso’s evocative entitled ‘Guernica’, painted in the immediate aftermath of the bombardment of the city. Picasso has memorialised the massacre through art for many who only know of Guernica because of his painting (as I had done).

It is this very memory of fascism, that seems to have receded from much of Europe except in its artistic expression, or worse instrumentalised in a horrific irony to instead further the very fascism it seems to loudly proclaim to never forget, that Spain in general and in Basque Country in particular still keeps alive. Not in a fetishisation of the past, but in an acute awareness of its afterlives and ongoing present. It is for this reason that solidarity with the resistance in Palestine - whatever our opinion of it – is not criminalised in Spain, the way it is in the UK, the US, and in Germany.

2.

https://thediplomatinspain.com/en/2024/05/03/the-basque-government-announces-two-grants-of-one-million-euros-to-unrwa/

3. https://www.catalannews.com/israel-hamas-war/item/entities-call-for-spain-to-welcome-palestinian-refugees-as-it-did-with-ukrainians

3. https://www.catalannews.com/israel-hamas-war/item/entities-call-for-spain-to-welcome-palestinian-refugees-as-it-did-with-ukrainians

Indeed, miniature reproductions of Picasso’s overtly anti-war Guernica are to be found plastered everywhere in Euskal Herria. In March 2024, following a pro-Palestine rally, San Sebastian had a ‘die-in’ where hundreds of people lay down next to a massive banner depicting Picasso’s Guernica. In Bilbao, a beautiful building in the main square is now being used as part bank and part pension (a type of motel). Much of the facade was made even more beautiful by an enormous banner which withdrew its hospitality from those aligned with the genocide. ‘Zionist you are not welcome’ it read simply and powerfully. These are not merely hollow demonstrations of solidarity: the Basque government has been supporting UNWRA for decades, and when the rest of the world was busy trying to ban UNWRA to ingratiate itself with Netanyahu’s war cabinet, the Basque government announced two grants of one million euros to UNWRA. 2 Multiple towns and cities in Basque Country are twinned with Palestinian cities, and the regional government, alongside that of Catalonia, has pushed for a policy that grants all Palestinians who come to Spain immediate refugee status.3 Trade unions (of which there are many), civil society organisations, artists, and activists from all parts of Euskal Herria have come together to express solidarity across concrete, material, emotional, and affective registers with Palestine.

Perhaps the most surprising takeaway from my very limited experience of the Basque Country was that this solidarity surprised me so much. A place that is unapologetically anti-genocide, anti-colonialism, and anti-war, appears unique and strange in the ‘civilised’ West. It is however not merely not unique, but also a reminder that the struggle for justice has always been global, and that ultimately in our thousands, in our millions we are always Palestinians.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Perhaps the most surprising takeaway from my very limited experience of the Basque Country was that this solidarity surprised me so much. A place that is unapologetically anti-genocide, anti-colonialism, and anti-war, appears unique and strange in the ‘civilised’ West. It is however not merely not unique, but also a reminder that the struggle for justice has always been global, and that ultimately in our thousands, in our millions we are always Palestinians.

Nivi Manchanda

Nivi Manchanda is a Reader (Associate Professor) in International Politics at Queen Mary, University of London. She is interested in questions of racism, empire, and borders and has published in, among other journals, International Affairs, Security Dialogue, Millennium, Current Sociology, and Third World Quarterly. She is the co-editor of Race and Racism in International Relations: Confronting the Global Colour Line (Routledge, 2014). Her monograph Imagining Afghanistan: the History and Politics of Imperial Knowledge (Cambridge University Press, 2020) was awarded the LHM Ling First Outstanding Book Prize by the British International Studies Association. She sits on the editorial board of International Studies Quarterly, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, and Security Dialogue. She was the co-editor in chief of the journal Politics from 2018 to 2021. She is currently working on a new book entitled Thinking the Border Otherwise: Global solidarity against Settler Colonialism and Racial Capitalism. She is a 2024 Philip Leverhulme Prize winner in Politics and International Relations.

Nivi Manchanda is a Reader (Associate Professor) in International Politics at Queen Mary, University of London. She is interested in questions of racism, empire, and borders and has published in, among other journals, International Affairs, Security Dialogue, Millennium, Current Sociology, and Third World Quarterly. She is the co-editor of Race and Racism in International Relations: Confronting the Global Colour Line (Routledge, 2014). Her monograph Imagining Afghanistan: the History and Politics of Imperial Knowledge (Cambridge University Press, 2020) was awarded the LHM Ling First Outstanding Book Prize by the British International Studies Association. She sits on the editorial board of International Studies Quarterly, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, and Security Dialogue. She was the co-editor in chief of the journal Politics from 2018 to 2021. She is currently working on a new book entitled Thinking the Border Otherwise: Global solidarity against Settler Colonialism and Racial Capitalism. She is a 2024 Philip Leverhulme Prize winner in Politics and International Relations.