Maia Gattás Vargas &

Francisca Khamis Giacoman

Francisca Khamis Giacoman

Cartas de agua

ES

Maia Gattás Vargas y Francisca Khamis Giacoman se conocieron en Cisjordania en 2019, donde Khamis Giacoman estaba realizando una residencia en Birzeit y Gattás Vargas viajaba filmando escenas de su documental “Viento del este” (2023). En este proyecto de intercambio de cartas, se proponen entablar un diálogo buscando abordar distintas memorias en torno al agua en el territorio de Palestina ocupada.

Para llevar a cabo esta iniciativa, tomarán archivos heterogéneos vinculados a este territorio: documentos históricos, fragmentos de películas como Port of Memory (2009) de Kamal Aljafari, y Salt of This Sea (2008) de Annemarie Jacir; archivos personales, que contemplan memorias de sus familias en diáspora (cartas, fotografías, relatos pertenecientes a la historia oral, etcétera); y registros propios que han realizado en sus viajes por Cisjordania, Palestina.

Proponen establecer un formato de correspondencia que facilite el inicio de un proceso de intercambio visual y textual. En este enfoque, la correspondencia no sólo se concibe como una técnica de archivo, sino también como una herramienta para entablar un diálogo activo con el archivo personal, enriquecido por la interacción con la memoria, el intercambio amistoso y la conexión con otras fuentes.

Las cartas irán apareciendo a lo largo del tiempo, haciendo de la publicación un proceso en crecimiento, donde no rige la inmediatez. Las cartas, originalmente redactadas en español, incluirán también su traducción, con la consiguiente pérdida que esta pueda conllevar, lo cual formará parte integral de la publicación.

Maia Gattás Vargas y Francisca Khamis Giacoman se conocieron en Cisjordania en 2019, donde Khamis Giacoman estaba realizando una residencia en Birzeit y Gattás Vargas viajaba filmando escenas de su documental “Viento del este” (2023). En este proyecto de intercambio de cartas, se proponen entablar un diálogo buscando abordar distintas memorias en torno al agua en el territorio de Palestina ocupada.

Para llevar a cabo esta iniciativa, tomarán archivos heterogéneos vinculados a este territorio: documentos históricos, fragmentos de películas como Port of Memory (2009) de Kamal Aljafari, y Salt of This Sea (2008) de Annemarie Jacir; archivos personales, que contemplan memorias de sus familias en diáspora (cartas, fotografías, relatos pertenecientes a la historia oral, etcétera); y registros propios que han realizado en sus viajes por Cisjordania, Palestina.

Proponen establecer un formato de correspondencia que facilite el inicio de un proceso de intercambio visual y textual. En este enfoque, la correspondencia no sólo se concibe como una técnica de archivo, sino también como una herramienta para entablar un diálogo activo con el archivo personal, enriquecido por la interacción con la memoria, el intercambio amistoso y la conexión con otras fuentes.

Las cartas irán apareciendo a lo largo del tiempo, haciendo de la publicación un proceso en crecimiento, donde no rige la inmediatez. Las cartas, originalmente redactadas en español, incluirán también su traducción, con la consiguiente pérdida que esta pueda conllevar, lo cual formará parte integral de la publicación.

EN

Maia and Francisca met in the West Bank in 2019, where Francisca was conducting a residency in Birzeit and Maia was filming scenes for her documentary “Viento del este” (2023). In this piece, they engage in a letter exchange and dialogue, seeking to address various memories surrounding water in the territory of occupied Palestine.

To carry out this initiative, they will draw from heterogeneous archives linked to this territory: historical documents, excerpts from films (such as Port of Memory by Kamal Aljafari or The Salt of This Sea by Anne-Marie Jacir), personal archives, which encompass memories of their families in diaspora (letters, photographs, oral history narratives, etc.), and their own records from their travels through Palestine.

They use a correspondance format that facilitates the initiation of a process of visual and textual exchange. In this approach, correspondence is not only conceived as an archival technique but also as a tool for engaging in active dialogue with the personal archive, enriched by interaction with memory, exchange with the other, and connection with other sources.

Maia and Francisca met in the West Bank in 2019, where Francisca was conducting a residency in Birzeit and Maia was filming scenes for her documentary “Viento del este” (2023). In this piece, they engage in a letter exchange and dialogue, seeking to address various memories surrounding water in the territory of occupied Palestine.

To carry out this initiative, they will draw from heterogeneous archives linked to this territory: historical documents, excerpts from films (such as Port of Memory by Kamal Aljafari or The Salt of This Sea by Anne-Marie Jacir), personal archives, which encompass memories of their families in diaspora (letters, photographs, oral history narratives, etc.), and their own records from their travels through Palestine.

They use a correspondance format that facilitates the initiation of a process of visual and textual exchange. In this approach, correspondence is not only conceived as an archival technique but also as a tool for engaging in active dialogue with the personal archive, enriched by interaction with memory, exchange with the other, and connection with other sources.

Carta #1: Las películas

Amiga

No te veo desde 2019. Tengo el recuerdo de que el día de nuestra despedida en la plaza Al-Manara de Ramallah, me hiciste probar una fruta nueva, no recuerdo su nombre, era rosada y espinosa por fuera y blanca y suave por dentro.

Estabas haciendo una residencia en Birzeit, trabajando con las historias de tu tía abuela Labibe. Creo que aún conservo un archivo con su voz en algún disco externo de aquella época.

También recuerdo que fuimos juntas al mar Muerto, viajando a dedo. Creo que dudamos durante mucho tiempo si esa parte de la playa a la que fuimos era una zona palestina o israelí. Las imágenes y sonidos que filmé aquella tarde están hoy al final de Viento del este, mi película. Ahí digo: “Palestina tiene tres mares: el Mediterráneo, el mar Rojo y el mar Muerto”. En una versión anterior de la voz en off decía: “tenía tres mares” en lugar de “tiene”, pero me pareció más acorde con mi posición política poder decir que aún le pertenecen. Cuando proyecté mi película en Londres en octubre, una chica del público me dijo que ese final estaba en sintonía con la canción que se canta actualmente en las manifestaciones por Gaza en todo el mundo: “From the river to the sea Palestine will be free”, esa frase que causó tanta polémica y censura. Acá, en Argentina, no cantamos eso en las marchas por Palestina, así que yo no la conocía, pero me alegró mucho saber que mi documental -que fue fruto de un trabajo de muchos años y que recién se estrenó en 2023- hizo eco con el presente.

La primera película que vi sobre Palestina fue en el año 2012 aproximadamente, su nombre es La sal de este mar. En esa época yo no sabía nada sobre el país de mis ancestros y fui a ver la película buscando información. Todo me resultaba confuso y críptico. Recuerdo que Soraya, la protagonista, quería llegar al mar y para eso debía entrar con Emad, su amigo palestino, de forma ilegal a Israel. Generosamente Annemarie Jacir, su directora, me cedió un fragmento de su película para que forme parte de la mía. Es la escena en que Soraya se adentra en las aguas del meditarráneo, por la zona de Jaffa, la ciudad donde estaba la casa de sus abuelos. La cámara está al ras del agua y nos hace sentir a los espectadores como si nos fuéramos a mojar. Ella nada en el mar pero al mismo tiempo no puede disfrutarlo porque está enojada.

25 de enero de 2024,

Bariloche, Argentina

Bariloche, Argentina

Amiga

No te veo desde 2019. Tengo el recuerdo de que el día de nuestra despedida en la plaza Al-Manara de Ramallah, me hiciste probar una fruta nueva, no recuerdo su nombre, era rosada y espinosa por fuera y blanca y suave por dentro.

Estabas haciendo una residencia en Birzeit, trabajando con las historias de tu tía abuela Labibe. Creo que aún conservo un archivo con su voz en algún disco externo de aquella época.

También recuerdo que fuimos juntas al mar Muerto, viajando a dedo. Creo que dudamos durante mucho tiempo si esa parte de la playa a la que fuimos era una zona palestina o israelí. Las imágenes y sonidos que filmé aquella tarde están hoy al final de Viento del este, mi película. Ahí digo: “Palestina tiene tres mares: el Mediterráneo, el mar Rojo y el mar Muerto”. En una versión anterior de la voz en off decía: “tenía tres mares” en lugar de “tiene”, pero me pareció más acorde con mi posición política poder decir que aún le pertenecen. Cuando proyecté mi película en Londres en octubre, una chica del público me dijo que ese final estaba en sintonía con la canción que se canta actualmente en las manifestaciones por Gaza en todo el mundo: “From the river to the sea Palestine will be free”, esa frase que causó tanta polémica y censura. Acá, en Argentina, no cantamos eso en las marchas por Palestina, así que yo no la conocía, pero me alegró mucho saber que mi documental -que fue fruto de un trabajo de muchos años y que recién se estrenó en 2023- hizo eco con el presente.

La primera película que vi sobre Palestina fue en el año 2012 aproximadamente, su nombre es La sal de este mar. En esa época yo no sabía nada sobre el país de mis ancestros y fui a ver la película buscando información. Todo me resultaba confuso y críptico. Recuerdo que Soraya, la protagonista, quería llegar al mar y para eso debía entrar con Emad, su amigo palestino, de forma ilegal a Israel. Generosamente Annemarie Jacir, su directora, me cedió un fragmento de su película para que forme parte de la mía. Es la escena en que Soraya se adentra en las aguas del meditarráneo, por la zona de Jaffa, la ciudad donde estaba la casa de sus abuelos. La cámara está al ras del agua y nos hace sentir a los espectadores como si nos fuéramos a mojar. Ella nada en el mar pero al mismo tiempo no puede disfrutarlo porque está enojada.

Letter #1: The movies

My friend,

I haven't seen you since 2019. I have the memory that on the day of our farewell in Al-Manara square in Ramallah, you made me taste a new fruit. I don't remember its name, it was pink and prickly on the outside and white and soft on the inside.

You were doing a residency in Birzeit, working with the stories of your great aunt Labibe. I think I still have a file with her voice on some external disk from that time…

I also remember going together to the Dead Sea, traveling by hitchhiking. I think we hesitated for a long time whether that piece of beach where we went was a Palestinian or an Israeli area. The images and sounds I filmed that afternoon are today at the end of Viento del este, my documentary film. There I say: “Palestine has three seas: the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea and the Dead Sea”. In a previous version of the voice-over I said: “Had three seas” instead of “Has” but it seemed more in line with my political position to be able to say that they still belong to it. When I screened my film in London last October, a girl in the audience told me that this ending was in tune with the song that is currently being sung in Gaza demonstrations around the world: “From the river to the sea Palestine will be free”, a phrase that caused so much controversy and censorship. Here, in Argentina, we don't sing that in the marches for Palestine, so I didn't know it, but I was very happy to know that my documentary - which was the result of many years of work and was released in 2023 - echoed with the present.

The first movie I saw about Palestine was in 2012 or so, its name is The Salt of this Sea. At that time I knew nothing about the country of my ancestors and I went to see the movie looking for information. Everything was confusing and cryptic to me. I remember that Soraya, the main character, wanted to reach the sea and for that she had to enter Israel illegally with Emad, her Palestinian friend. Annemarie Jacir, its director, generously gave me a fragment of her film to be part of mine. It is the scene in which Soraya enters the waters of the Mediterranean, in the area of Jaffa, the city where her grandparents' house used to be. She swims in the sea but at the same time cannot enjoy it because she is angry.

January 25, 2024,

Bariloche, Argentina

Bariloche, Argentina

My friend,

I haven't seen you since 2019. I have the memory that on the day of our farewell in Al-Manara square in Ramallah, you made me taste a new fruit. I don't remember its name, it was pink and prickly on the outside and white and soft on the inside.

You were doing a residency in Birzeit, working with the stories of your great aunt Labibe. I think I still have a file with her voice on some external disk from that time…

I also remember going together to the Dead Sea, traveling by hitchhiking. I think we hesitated for a long time whether that piece of beach where we went was a Palestinian or an Israeli area. The images and sounds I filmed that afternoon are today at the end of Viento del este, my documentary film. There I say: “Palestine has three seas: the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea and the Dead Sea”. In a previous version of the voice-over I said: “Had three seas” instead of “Has” but it seemed more in line with my political position to be able to say that they still belong to it. When I screened my film in London last October, a girl in the audience told me that this ending was in tune with the song that is currently being sung in Gaza demonstrations around the world: “From the river to the sea Palestine will be free”, a phrase that caused so much controversy and censorship. Here, in Argentina, we don't sing that in the marches for Palestine, so I didn't know it, but I was very happy to know that my documentary - which was the result of many years of work and was released in 2023 - echoed with the present.

The first movie I saw about Palestine was in 2012 or so, its name is The Salt of this Sea. At that time I knew nothing about the country of my ancestors and I went to see the movie looking for information. Everything was confusing and cryptic to me. I remember that Soraya, the main character, wanted to reach the sea and for that she had to enter Israel illegally with Emad, her Palestinian friend. Annemarie Jacir, its director, generously gave me a fragment of her film to be part of mine. It is the scene in which Soraya enters the waters of the Mediterranean, in the area of Jaffa, the city where her grandparents' house used to be. She swims in the sea but at the same time cannot enjoy it because she is angry.

Años después, en el Festival de Doc Buenos Aires, conocí al cineasta palestino Kamal Aljafari. En su película Port of memory (2010) también aparece el deseo y la nostalgia por el agua perdida. También filmó en Jaffa, un lugar que para los palestinos se convirtió en símbolo de desposesión y exilio.

Years later, at Doc Buenos Aires Film Festival, I met the Palestinian filmmaker Kamal Aljafari. In his film Port of Memory (2010) there also appears the desire and nostalgia for the lost water. He also filmed in Jaffa, a place that for Palestinians became a symbol of dispossession and exile.

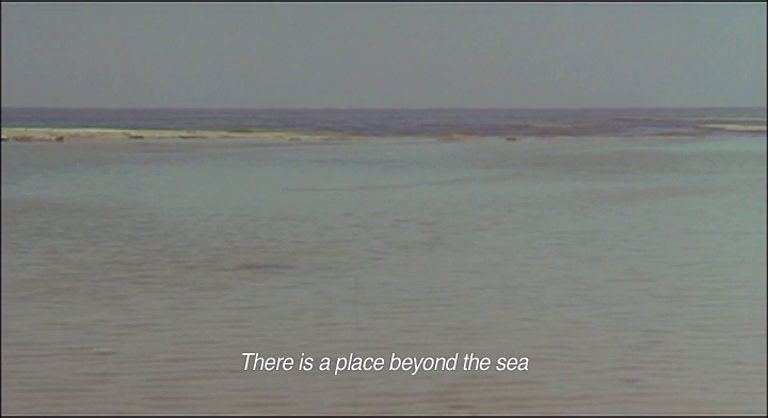

Aljafari toma un fragmento del musical israelí Kazablan (1974), donde aparece la canción Yesh Makom (Hay un lugar), interpretada por Yehoran Ga'om. En esa escena, el protagonista se encuentra atrapado entre las imágenes del mar del pasado y el del presente. La forma de palimpsesto temporal siempre me pareció la manera más justa de experimentar el tiempo -¡quizá porque leo demasiado a Walter Benjamin!-. Cuando lo conocí, Kamal me contó algo que atesoro y que nunca voy a olvidar: me dijo que solía ir a la orilla del mar Mediterráneo a recoger escombros y azulejos de las casas palestinas destruidas por el Estado de Israel. Le gustaba conservar esos restos, esos recuerdos materiales fragmentarios que traen las mareas.

Aljafari takes a fragment from the Israeli musical Kazablan (1974), where the song Yesh Makom (There is a place), performed by Yehoran Ga'om, appears. In that scene the protagonist finds himself trapped between the images of the sea of the past and that of the present. The form of temporal palimpsest always seemed to me to be the fairest way to experience time -perhaps because I read too much Walter Benjamin!. When I met Kamal he told me something that I treasure and that I will never forget: that he often went to the shore of the Mediterranean Sea to collect debris and tiles from the Palestinian houses demolished by the state of Israel. He liked to keep those remains, those fragmentary material memories that the tidal movements brought back.

Carta #2: Ver el mar

Hola amiga

22 de Enero, 2024,

Concón, Chile

Concón, Chile

Hola amiga

Letter #2: to see the sea

January 22, 2024,

Concón, Chile

Concón, Chile

“Buenos días, buenas tardes, buenas noches. Porque no sé a qué hora del día leerás esto. El tiempo pasa, pero lo que hace sentido de la humanidad sigue igual”. Así parte John Berger su lectura de Letters from Gaza de Ghassan Kanafani.[1]

Empecé a escribirte esta carta sentada frente al mar pacífico de Concón. Siempre he querido que el mar sea parte de mi paisaje, pero desafortunadamente nací y crecí en Santiago. Y la verdad no tengo conciencia de cuándo fue la primera vez que vi el mar. Cómo sientes aquello que nunca viste? Una concha de loco en la oreja para imaginar juntas aquello que nunca pudimos tocar.

Toda esta agua al frente mío y detrás incendios que no paran de crecer. Pensar en el poder del agua. Un chorro de agua cae desde la quebrada junto al edificio, el único espacio donde no pueden construir. Ese chorro de agua evita a las inmobiliarias destruir ese terreno, ese mismo chorro de agua podría estar ahora mismo evitando todas aquellas casas que se están incendiando en este momento en Valparaíso.

Pienso en el agua como el archivo, como ese chorro que pasa y cambia el territorio para quienes vienen a habitarlo después.

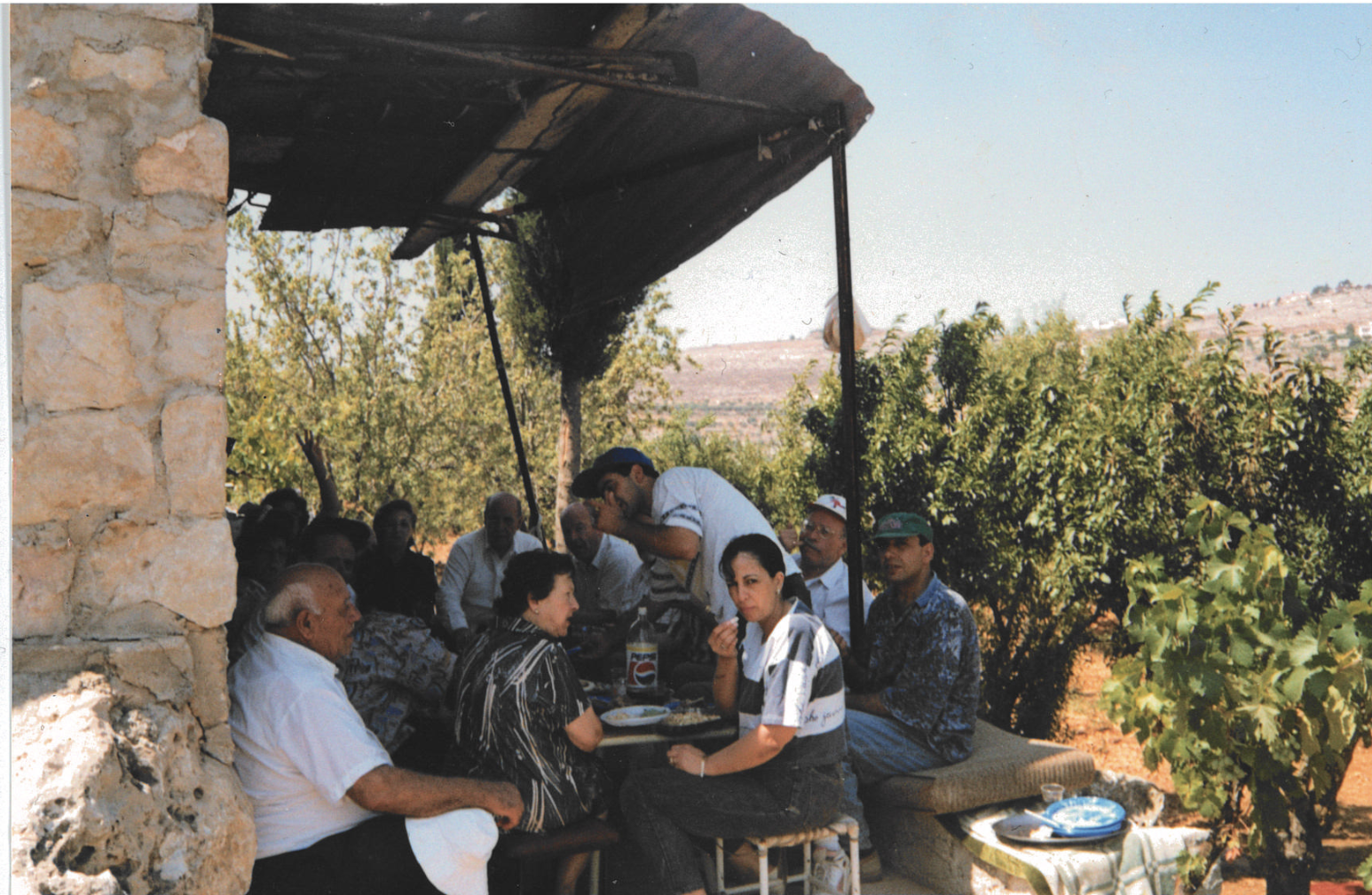

Hace ya 5 años que nos encontramos en Palestina, donde llegué hace 11 años por primera vez; impulsada por esas historias que tanto escuché sobre un territorio que no sentía parte mio. Mi primer viaje estuvo guiado principalmente por dos fotos: La primera, donde aparecen mis parientes sentados en lo que pareciera ser un almuerzo en el campo, en Al Makhrour. La segunda es una foto de mi abuelo parado en el muro en Haifa junto a otra persona, frente a uno de los 3 mares que Palestina tiene.

Empecé a escribirte esta carta sentada frente al mar pacífico de Concón. Siempre he querido que el mar sea parte de mi paisaje, pero desafortunadamente nací y crecí en Santiago. Y la verdad no tengo conciencia de cuándo fue la primera vez que vi el mar. Cómo sientes aquello que nunca viste? Una concha de loco en la oreja para imaginar juntas aquello que nunca pudimos tocar.

Toda esta agua al frente mío y detrás incendios que no paran de crecer. Pensar en el poder del agua. Un chorro de agua cae desde la quebrada junto al edificio, el único espacio donde no pueden construir. Ese chorro de agua evita a las inmobiliarias destruir ese terreno, ese mismo chorro de agua podría estar ahora mismo evitando todas aquellas casas que se están incendiando en este momento en Valparaíso.

Pienso en el agua como el archivo, como ese chorro que pasa y cambia el territorio para quienes vienen a habitarlo después.

Hace ya 5 años que nos encontramos en Palestina, donde llegué hace 11 años por primera vez; impulsada por esas historias que tanto escuché sobre un territorio que no sentía parte mio. Mi primer viaje estuvo guiado principalmente por dos fotos: La primera, donde aparecen mis parientes sentados en lo que pareciera ser un almuerzo en el campo, en Al Makhrour. La segunda es una foto de mi abuelo parado en el muro en Haifa junto a otra persona, frente a uno de los 3 mares que Palestina tiene.

“Good morning, good afternoon, good evening. Because I don't know at what time of day you'll read this. Time passes, but what makes sense of humanity remains the same.” That's how John Berger begins the reading of Letters from Gaza by Ghassan Kanafani. [1]

I started writing you this letter sitting in front of the Pacific Sea in Concón. I've always wanted the sea to be part of my landscape, but unfortunately, I was born and raised in Santiago. And the truth is, I'm not aware of when I first saw the sea. How do you feel something you've never seen? An abalone shell in the ear to imagine together what we could never touch.

All this water in front of me and behind the wildfires that don't stop growing. I am thinking about the power of water. A stream of water falls from the creek next to the building, the only space where they can't build. That stream of water prevents real estate companies from destroying that land, that same stream of water could be right now preventing all those houses from burning in Valparaíso.

I think of water as the archive, as that stream that passes and changes the territory for those who come to inhabit it afterward.

It's been 5 years since we met in Palestine, where I arrived 11 years ago for the first time; driven by those stories I heard so much about a territory that didn't feel like I belonged to. My first trip was guided mainly by two photos: the first one, where my relatives appear sitting at what seems to be a lunch in the field, in Al Makhrour. The second is a photo of my grandfather standing on the wall in Haifa next to another person, facing one of Palestine’s 3 seas.

I started writing you this letter sitting in front of the Pacific Sea in Concón. I've always wanted the sea to be part of my landscape, but unfortunately, I was born and raised in Santiago. And the truth is, I'm not aware of when I first saw the sea. How do you feel something you've never seen? An abalone shell in the ear to imagine together what we could never touch.

All this water in front of me and behind the wildfires that don't stop growing. I am thinking about the power of water. A stream of water falls from the creek next to the building, the only space where they can't build. That stream of water prevents real estate companies from destroying that land, that same stream of water could be right now preventing all those houses from burning in Valparaíso.

I think of water as the archive, as that stream that passes and changes the territory for those who come to inhabit it afterward.

It's been 5 years since we met in Palestine, where I arrived 11 years ago for the first time; driven by those stories I heard so much about a territory that didn't feel like I belonged to. My first trip was guided mainly by two photos: the first one, where my relatives appear sitting at what seems to be a lunch in the field, in Al Makhrour. The second is a photo of my grandfather standing on the wall in Haifa next to another person, facing one of Palestine’s 3 seas.

Esa primera vez que fui a Palestina fue en el 2014. Crucé por Jordania donde estuve alrededor de 8 horas esperando que me dejaran cruzar. Los soldados israelíes me preguntaron de todo, de todas las maneras posibles. Al principio con algo de paciencia y al final con bastante violencia. Ahí fue cuando ellos me reconocieron como Palestina y cuando ese territorio se sintió también parte mía.

No he visto La sal de este mar. Pero tu relato sobre Soraya me hace pensar en María. En mi estadía en Beitjala, en la casa de mis parientes. Familia que yo no conocía, pero que me recibieron como una de sus hijas. Me armaron una cama al lado de la de María, mi prima menor. En ese tiempo ella tenía 18 años y nunca había visto el mar. Cuando llegué, ella me contó que estaba esperando hacía unos meses su permiso para “cruzar” a Israel. Luego de una semana, el permiso llegó. Entonces planeamos una ida a Tel Aviv, a ver el mar. Cruzamos el checkpoint en bus después de varias horas, a pesar de la cercanía. Llegamos a la estación con una primera misión: comprar un traje de baño para María. Yo venía con la idea radical de no dejar ni un peso ahí, pero la vida es diferente cuando en realidad pasa.

Encontramos un lugar en la estación, ella sacó un par de trajes de baño y se metió al probador. En eso, el vendedor me pregunta de donde soy y le dije de Chile y mi prima dijo de Colombia (donde parte de su familia vive hoy). Después de unos minutos en silencio, no me contuve en decir, pero somos también Palestinas. Cambió su cara y nos empezó a gritar diciendo que él le disparaba a los palestinos. Agarramos nuestras cosas y nos fuimos corriendo de ahí.

Fuimos a la playa sin traje de baño, y la primera visita al mar con sabor amargo me hizo entender que la vida en diáspora forma una identidad que no siempre calza con la de quienes aún viven ahí. Vivir escuchando el mar desde una concha de loco, no siempre te hace entender los peligros de las marejadas.

No he visto La sal de este mar. Pero tu relato sobre Soraya me hace pensar en María. En mi estadía en Beitjala, en la casa de mis parientes. Familia que yo no conocía, pero que me recibieron como una de sus hijas. Me armaron una cama al lado de la de María, mi prima menor. En ese tiempo ella tenía 18 años y nunca había visto el mar. Cuando llegué, ella me contó que estaba esperando hacía unos meses su permiso para “cruzar” a Israel. Luego de una semana, el permiso llegó. Entonces planeamos una ida a Tel Aviv, a ver el mar. Cruzamos el checkpoint en bus después de varias horas, a pesar de la cercanía. Llegamos a la estación con una primera misión: comprar un traje de baño para María. Yo venía con la idea radical de no dejar ni un peso ahí, pero la vida es diferente cuando en realidad pasa.

Encontramos un lugar en la estación, ella sacó un par de trajes de baño y se metió al probador. En eso, el vendedor me pregunta de donde soy y le dije de Chile y mi prima dijo de Colombia (donde parte de su familia vive hoy). Después de unos minutos en silencio, no me contuve en decir, pero somos también Palestinas. Cambió su cara y nos empezó a gritar diciendo que él le disparaba a los palestinos. Agarramos nuestras cosas y nos fuimos corriendo de ahí.

Fuimos a la playa sin traje de baño, y la primera visita al mar con sabor amargo me hizo entender que la vida en diáspora forma una identidad que no siempre calza con la de quienes aún viven ahí. Vivir escuchando el mar desde una concha de loco, no siempre te hace entender los peligros de las marejadas.

The first time I went to Palestine was in 2014. I crossed through Jordan where I spent about 8 hours waiting to be allowed to cross. They asked me everything, in every possible way. At first with some patience and in the end with quite some violence. That's when they recognized me as Palestinian and when for the first time I felt I belonged there.

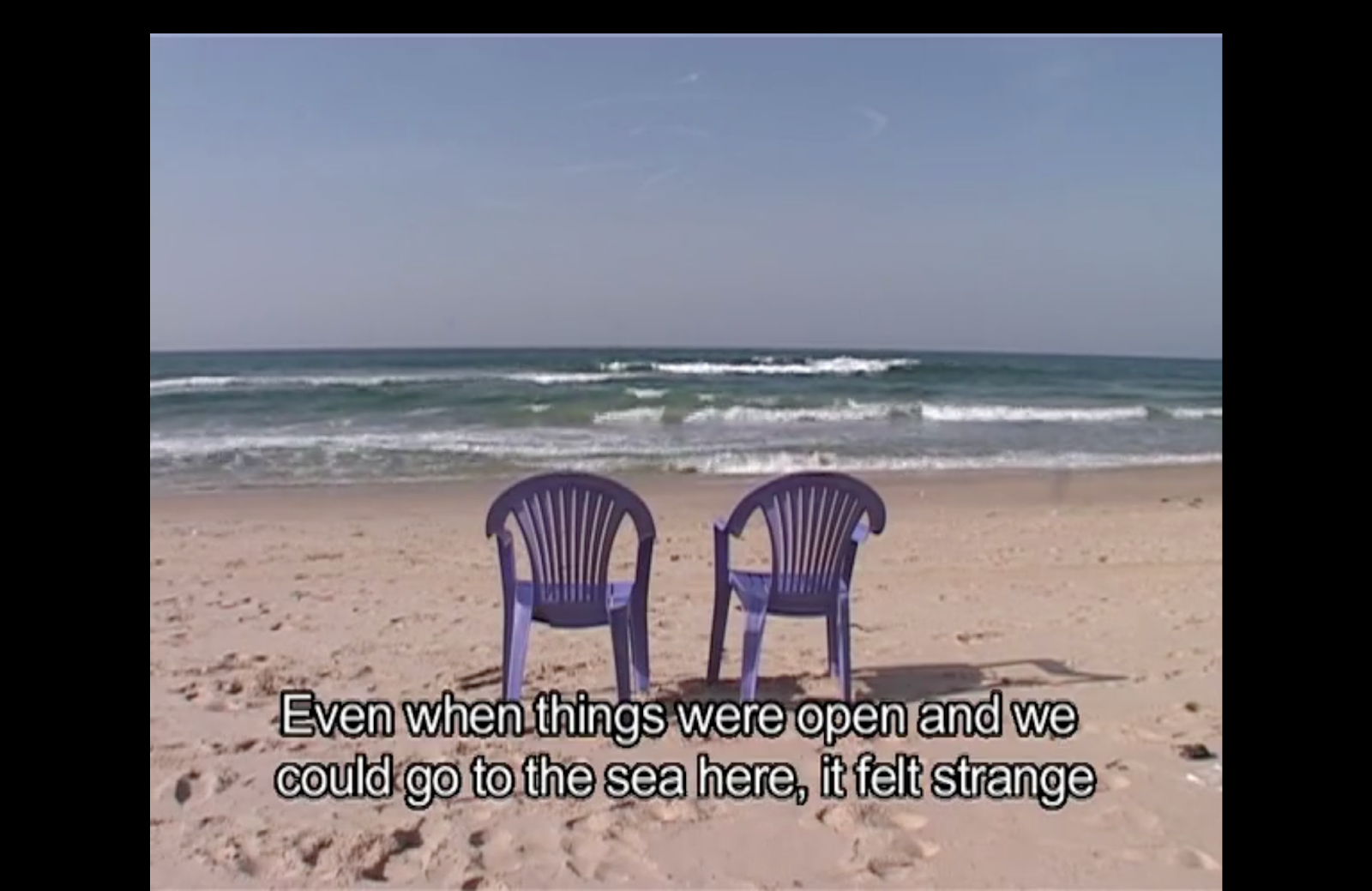

I haven't seen Salt of This Sea. But your story about Soraya makes me think of María and my stay in Beit Jala, at my relatives' house. I didn't know them before, but they welcomed me as one of their own daughters. They set up a bed for me next to María's, my younger cousin. At that time she was 18 and had never seen the sea. When I arrived, she told me she had been waiting for her permit to cross for a few months. After a week, the permit arrived. So we planned a trip to Tel Aviv. We crossed the checkpoint by bus after several hours, despite the proximity. We arrived at the station with a first mission: to buy a swimsuit for María. I went there with the radical idea of not leaving a single penny there, but life is different when it actually happens. We found a place at the station and she picked a couple of swimsuits and went to the fitting room. Then, the salesman asked me where I was from. I said Chile and my cousin said Colombia (where part of her family lives today). After a few minutes of silence, I couldn't help but say, but we’re also Palestinians. His expression changed and he started shouting at us saying he would shoot Palestinians. We grabbed our things and ran out of there.

We went to the beach without swimsuits, and the first visit to the sea with a bitter taste made me understand that life in diaspora forms an identity that doesn't always fit with those who still live there. Living listening to the sea from a conch shell doesn't always make you understand the dangers of the swells.

I haven't seen Salt of This Sea. But your story about Soraya makes me think of María and my stay in Beit Jala, at my relatives' house. I didn't know them before, but they welcomed me as one of their own daughters. They set up a bed for me next to María's, my younger cousin. At that time she was 18 and had never seen the sea. When I arrived, she told me she had been waiting for her permit to cross for a few months. After a week, the permit arrived. So we planned a trip to Tel Aviv. We crossed the checkpoint by bus after several hours, despite the proximity. We arrived at the station with a first mission: to buy a swimsuit for María. I went there with the radical idea of not leaving a single penny there, but life is different when it actually happens. We found a place at the station and she picked a couple of swimsuits and went to the fitting room. Then, the salesman asked me where I was from. I said Chile and my cousin said Colombia (where part of her family lives today). After a few minutes of silence, I couldn't help but say, but we’re also Palestinians. His expression changed and he started shouting at us saying he would shoot Palestinians. We grabbed our things and ran out of there.

We went to the beach without swimsuits, and the first visit to the sea with a bitter taste made me understand that life in diaspora forms an identity that doesn't always fit with those who still live there. Living listening to the sea from a conch shell doesn't always make you understand the dangers of the swells.

Volviendo a Kanafani, la frase que envía con tanta rotundidad a Mustafá en la carta desde Gaza me da la vuelta: “No, me quedaré aquí y no me iré nunca.”

Después de leer tu carta, me quedé pensando en el palimpsesto y justamente ayer un amigo me compartió una cita de Susan Sontag que me hizo acordar de ti: “El tiempo existe para que no ocurra todo a la vez... y el espacio existe para que no te ocurra todo a ti.”

Te mando un abrazo amiga mia,

Hay muchas cosas que me quedan por decir, más chorros de agua para las próximas cartas.

Después de leer tu carta, me quedé pensando en el palimpsesto y justamente ayer un amigo me compartió una cita de Susan Sontag que me hizo acordar de ti: “El tiempo existe para que no ocurra todo a la vez... y el espacio existe para que no te ocurra todo a ti.”

Te mando un abrazo amiga mia,

Hay muchas cosas que me quedan por decir, más chorros de agua para las próximas cartas.

Returning to Kanafani, the phrase he sends so emphatically to Mustafa in the letter from Gaza turns me around: “No, I'll stay here, and I won't ever leave.”

After reading your letter, I kept thinking about the palimpsest and just yesterday a friend shared a quote from Susan Sontag that made me remember you: “Time exists in order that everything doesn't happen all at once… and space exists so that everything doesn't happen to you.”

There are many things left for me to say, more streams of water for the next letters.

After reading your letter, I kept thinking about the palimpsest and just yesterday a friend shared a quote from Susan Sontag that made me remember you: “Time exists in order that everything doesn't happen all at once… and space exists so that everything doesn't happen to you.”

There are many things left for me to say, more streams of water for the next letters.

Carta #3: La unión de los ríos

De un incendio a otro incendio, de un río a otro río.

Acá, en la Patagonia, donde vivo parte del año, cada verano hay nuevos incendios, muchos de ellos son intencionales. Hace un par de semanas perdí la vista que tengo en mis ventanas a causa del humo que trajo el viento. (Yo perdí mi vista, pero el bosque perdió miles de hectáreas!).

Me acuerdo que unos pocos días antes te había mostrado por videollamada la montaña que veo desde mi escritorio, pero ese día ya no se veía nada. Se había perdido el horizonte, la amplitud a la cuál me acostumbré. Esa noche me costó dormir. Era como si hubiese perdido el sentido de la orientación y también tenía miedo que mientras dormía el fuego avanzara.

Por suerte vivo frente a un arroyo que conecta dos lagos: el lago Gutierrez con el lago Nahuel Huapi (el más grande de esta región). Los arroyos son también cortafuegos. En el libro de una poeta de mi ciudad, Graciela Cros, que leí el otro día dice: “Un cortafuegos es un espacio de terreno que no posee ningún tipo de combustible, de esta forma los incendios forestales no se pueden esparcir.

Existen cortafuegos naturales, artificiales o creados. Los naturales son simplemente un terreno con escaso o ningún tipo de vegetación, como los ríos; los artificiales pueden ser carreteras; y los creados son hechos por los bomberos durante el incendio, deforestando el área seleccionada”.

El arroyo que corre enfrente de mi casa, no solo impide el avance de un incendio, también, como decís en tu carta, impide que se construyan más casas en esa zona, es decir, gracias a él aún tengo mi vista abierta y despejada.

Me pregunto ¿Cuál es el cortafuego de Gaza? ¿Cuál es el límite? ¿Cómo podemos construir un cortafuego (cease fire!?). Quizás el mar meditarráneo en las costas de Gaza más que un cortafuego actúa como causante del incendio. El otro día unos amigos de mi madre le dijeron que cuando termine la “guerra” se van a mudar a Israel porque “les gusta vivir cerca del mar”.

A veces me gusta visualizar los territorios a través de sus mapas hídricos. Imaginar cómo se conectan todas las aguas, cómo todas están relacionadas. Con mi película intenté unir tres territorios importantes para mi historia a través de circuitos de agua: partiendo por los múltiples estados del agua en Bariloche (nieve, arroyos, lagos, lluvias); pasando por el gran Río de La Plata en Buenos Aires, donde mi padre murió ahogado en un accidente, y finalmente llegando al Río Jordán en Cisjordania, lugar de donde proviene el significado de mi apellido paterno: Gattás, que significa “buzo” o “bautismo”.

Quería construir un mapa audiovisual afectivo y acuático. Me obsesionaba pensar cómo hacer convivir visual y sonoramente estos paisajes tan distantes. Entre el río Jordán y el río de La Plata hay 12,896 km de distancia; Entre el río de La Plata y el arroyo frente a mi casa en Bariloche hay 1,594 km. Si bien ambos territorios tienen en común que fueron -y aún son- nombrados como “desiertos”, para así poder ser colonizados, la vegetación, los colores de Bariloche y Palestina son muy distintos. Verdes y azules predominan en mi paisaje cotidiano y colores tierra y amarillos en el territorio de mis antepasados.

8 de febrero 2024,

Bariloche, Argentina

Bariloche, Argentina

De un incendio a otro incendio, de un río a otro río.

Acá, en la Patagonia, donde vivo parte del año, cada verano hay nuevos incendios, muchos de ellos son intencionales. Hace un par de semanas perdí la vista que tengo en mis ventanas a causa del humo que trajo el viento. (Yo perdí mi vista, pero el bosque perdió miles de hectáreas!).

Me acuerdo que unos pocos días antes te había mostrado por videollamada la montaña que veo desde mi escritorio, pero ese día ya no se veía nada. Se había perdido el horizonte, la amplitud a la cuál me acostumbré. Esa noche me costó dormir. Era como si hubiese perdido el sentido de la orientación y también tenía miedo que mientras dormía el fuego avanzara.

Por suerte vivo frente a un arroyo que conecta dos lagos: el lago Gutierrez con el lago Nahuel Huapi (el más grande de esta región). Los arroyos son también cortafuegos. En el libro de una poeta de mi ciudad, Graciela Cros, que leí el otro día dice: “Un cortafuegos es un espacio de terreno que no posee ningún tipo de combustible, de esta forma los incendios forestales no se pueden esparcir.

Existen cortafuegos naturales, artificiales o creados. Los naturales son simplemente un terreno con escaso o ningún tipo de vegetación, como los ríos; los artificiales pueden ser carreteras; y los creados son hechos por los bomberos durante el incendio, deforestando el área seleccionada”.

El arroyo que corre enfrente de mi casa, no solo impide el avance de un incendio, también, como decís en tu carta, impide que se construyan más casas en esa zona, es decir, gracias a él aún tengo mi vista abierta y despejada.

Me pregunto ¿Cuál es el cortafuego de Gaza? ¿Cuál es el límite? ¿Cómo podemos construir un cortafuego (cease fire!?). Quizás el mar meditarráneo en las costas de Gaza más que un cortafuego actúa como causante del incendio. El otro día unos amigos de mi madre le dijeron que cuando termine la “guerra” se van a mudar a Israel porque “les gusta vivir cerca del mar”.

A veces me gusta visualizar los territorios a través de sus mapas hídricos. Imaginar cómo se conectan todas las aguas, cómo todas están relacionadas. Con mi película intenté unir tres territorios importantes para mi historia a través de circuitos de agua: partiendo por los múltiples estados del agua en Bariloche (nieve, arroyos, lagos, lluvias); pasando por el gran Río de La Plata en Buenos Aires, donde mi padre murió ahogado en un accidente, y finalmente llegando al Río Jordán en Cisjordania, lugar de donde proviene el significado de mi apellido paterno: Gattás, que significa “buzo” o “bautismo”.

Quería construir un mapa audiovisual afectivo y acuático. Me obsesionaba pensar cómo hacer convivir visual y sonoramente estos paisajes tan distantes. Entre el río Jordán y el río de La Plata hay 12,896 km de distancia; Entre el río de La Plata y el arroyo frente a mi casa en Bariloche hay 1,594 km. Si bien ambos territorios tienen en común que fueron -y aún son- nombrados como “desiertos”, para así poder ser colonizados, la vegetación, los colores de Bariloche y Palestina son muy distintos. Verdes y azules predominan en mi paisaje cotidiano y colores tierra y amarillos en el territorio de mis antepasados.

Letter #3: The union of rivers

From one fire to another fire, from one river to another river.

Here, in Patagonia, where I live part of the year, every summer there are new fires, many of them intentional. A couple of weeks ago I lost the view I have in my windows because of the smoke brought by the wind (I lost my sight, but the forest lost thousands of acres!).

I remember that a few days before, I had shown you by videocall the mountain I see from my desk, but that day nothing was visible anymore… The horizon was gone, the breadth to which I have become accustomed. That night I had trouble sleeping. It was as if I had lost my sense of direction and I was also afraid that, while I slept, the fire would advance.

Luckily, I live in front of a stream that connects two lakes: Lake Gutierrez with Lake Nahuel Huapi (the largest in this region). The streams are firebreaks. In the book of the poet Graciela Cross that I read the other day she says: “A firebreak is a space of land that does not have any kind of fuel, so forest fires cannot spread.

There are natural, artificial or created firebreaks. The natural ones are simply land with little or no vegetation, such as rivers; the artificial ones can be roads; and the created ones are made by the firefighters during the fire, deforesting the selected area.

The creek that runs in front of my house, not only prevents the advance of a fire, it also, as you say in your letter, prevents more houses from being built in that area, that is, thanks to it I still have my view open and clear”.

I wonder what is the firebreak in Gaza, what is the limit, how can we build a firebreak (cease fire!?). I think maybe the Mediterranean Sea on the shores of Gaza acts more as a firebreak than a firebreak. The other day some friends of my mother's told her that: When the “war” is over she was going to move to Israel, because “they like to live near the sea”.

Sometimes I like to visualize territories through their water maps. To imagine how all the waters are connected, how they are all related. With my film I tried to link three important territories for my story through water circuits: starting with the multiple states of water in Bariloche (snow, streams, lakes, rains); going through the great Rio de La Plata in Buenos Aires, where my father died in an accident, and finally arriving at the Jordan River in the West Bank, the place where the meaning of my last name comes from: Gattas, which means “diver” or “baptism”.

I wanted to build an affective and aquatic audiovisual map. I was obsessed with thinking how to make these distant landscapes coexist visually and sonically. Between the Jordan River and the Rio de La Plata there are 12,896 km of distance; between the Rio de La Plata and the stream in front of my house in Bariloche there are 1,594 km. Although both territories, Palestine and Patagonia, have in common that they were -and still are- named as “deserts”, in order to be colonized, the vegetation, the colors of their landscapes are very different. Greens and blues predominate in my daily space and earth colors and yellows in the land of my ancestors.

February 8, 2024,

Bariloche, Argentina

Bariloche, Argentina

From one fire to another fire, from one river to another river.

Here, in Patagonia, where I live part of the year, every summer there are new fires, many of them intentional. A couple of weeks ago I lost the view I have in my windows because of the smoke brought by the wind (I lost my sight, but the forest lost thousands of acres!).

I remember that a few days before, I had shown you by videocall the mountain I see from my desk, but that day nothing was visible anymore… The horizon was gone, the breadth to which I have become accustomed. That night I had trouble sleeping. It was as if I had lost my sense of direction and I was also afraid that, while I slept, the fire would advance.

Luckily, I live in front of a stream that connects two lakes: Lake Gutierrez with Lake Nahuel Huapi (the largest in this region). The streams are firebreaks. In the book of the poet Graciela Cross that I read the other day she says: “A firebreak is a space of land that does not have any kind of fuel, so forest fires cannot spread.

There are natural, artificial or created firebreaks. The natural ones are simply land with little or no vegetation, such as rivers; the artificial ones can be roads; and the created ones are made by the firefighters during the fire, deforesting the selected area.

The creek that runs in front of my house, not only prevents the advance of a fire, it also, as you say in your letter, prevents more houses from being built in that area, that is, thanks to it I still have my view open and clear”.

I wonder what is the firebreak in Gaza, what is the limit, how can we build a firebreak (cease fire!?). I think maybe the Mediterranean Sea on the shores of Gaza acts more as a firebreak than a firebreak. The other day some friends of my mother's told her that: When the “war” is over she was going to move to Israel, because “they like to live near the sea”.

Sometimes I like to visualize territories through their water maps. To imagine how all the waters are connected, how they are all related. With my film I tried to link three important territories for my story through water circuits: starting with the multiple states of water in Bariloche (snow, streams, lakes, rains); going through the great Rio de La Plata in Buenos Aires, where my father died in an accident, and finally arriving at the Jordan River in the West Bank, the place where the meaning of my last name comes from: Gattas, which means “diver” or “baptism”.

I wanted to build an affective and aquatic audiovisual map. I was obsessed with thinking how to make these distant landscapes coexist visually and sonically. Between the Jordan River and the Rio de La Plata there are 12,896 km of distance; between the Rio de La Plata and the stream in front of my house in Bariloche there are 1,594 km. Although both territories, Palestine and Patagonia, have in common that they were -and still are- named as “deserts”, in order to be colonized, the vegetation, the colors of their landscapes are very different. Greens and blues predominate in my daily space and earth colors and yellows in the land of my ancestors.

Para la investigación de mi película busqué miles de imágenes en Internet sobre el agua en Palestina. -descargar archivos en mi computadora es una de las cosas que más me gusta hacer, puedo pasar horas!- Y en esa búsqueda frenética encontré estas fotos aéreas en el sitio de Library of Congress dentro de la colección fotográfica de Eric and Edith Matson:

[2]

[2] They were photographers within The American Colony, 1881-1934.

For the research of my film, I searched thousands of images on the Internet about water in Palestine - downloading files on my computer is one of my favorite things to do, I can spend hours!- And in that frantic search, I found these aerial photos on the Library of Congress site within the Eric and Edith Matson photographic Collection:

[2]

Tiempo después, en el Archivo General de la Nación de Argentina, encontré una pieza audiovisual sobre los ríos de la Patagonia, su similitud estética me pareció asombrosa y este video terminó siendo parte de mi documental:

Some time later, in the General Archive of the Nation of Argentina, I found an audiovisual about the rivers of Patagonia, its aesthetic similarity seemed amazing to me and this video ended up being part of my film:

Parece que la conexión con el río Jordán no es sólo visual, navegando por los ríos infinitos de Internet, llegué a un dato que me puso la piel de gallina: el primer nombre del río de La Plata fue Río Jordán. El conquistador Américo Vespucio, en 1502, le otorgó ese nombre erróneamente.

It seems that the connection with the Jordan River is not only visual, surfing the infinite rivers of the Internet, I came across a fact that gave me goosebumps: the first name of the La Plata River was the Jordan River. The conqueror Amerigo Vespucci, in 1502, gave it that name erroneously.

Carta #4: Miedo al olvido

Hola Maia,

12-20 de abril de 2024

Santiago, CL / Amsterdam, NL

Santiago, CL / Amsterdam, NL

Hola Maia,

Letter #4: Fear of Forgetting

Hola Maia,

April 12-20, 2024

Santiago, CL / Amsterdam, NL

Santiago, CL / Amsterdam, NL

Hola Maia,

Recuerdo la primera fruta que probamos juntas. Parecía una pitahaya, pero en mi memoria también era una tuna.[3]

[3] Tuna: Prickly pear fruit or cactus fruit.

I remember the first fruit we tasted together. It seemed to be dragon fruit, but in my memory, it was also a tuna.[3]

Fruto de tuna de Ancash, Perú by Edgar Amador Espinoza M.

Esta carta va así: Fragmentos de notas que te he escrito y que no he podido unir en un todo coherente. Me resisto a pensar que estas cartas las escribo para publicarlas. Quiero escribirte, pero no puedo evitar pensar en aquellos otros que accederán a estos textos y de qué manera lo harán. En inglés y saltándose partes. Esta cuarta carta la escribo para ti y para mí, y para nuestros recuerdos.

Hoy quiero archivar dos cosas: las tunas y mi miedo al olvido.

Hoy quiero archivar dos cosas: las tunas y mi miedo al olvido.

This letter goes like this: Fragments of notes I've written to you and haven't been able to put together into a coherent whole. I may resist the thought that these letters are being written to be published. I want to write to you, but I can't help but think about those others who will access these texts and in what ways they will do so. In English and skipping parts. This fourth letter I write to you and me, y para nuestros recuerdos.

Today I want to archive two things: las tunas and my fear of forgetting.

Today I want to archive two things: las tunas and my fear of forgetting.

Cuando leí tu carta y tu reflexión sobre los colores de

los paisajes, recordé un mito que se escucha aquí en Chile en relación a la magnitud de la diáspora palestina.

[4]

La típica pregunta de por qué llegaron a Chile. Una vez me dijeron que una de las razones era el clima y la similitud en la agricultura; en ambos lugares se cosechan cactus y tunas. Ayer comí la primera tuna del año que venía de Tiltil. Busco en Google la distancia entre Al Makhrour y Tiltil: 13.225 km. [

[4]

Se cree que los palestinos en Chile (en árabe: فلسطينيو تشيلي) son la mayor comunidad palestina fuera del mundo árabe. Hay unos 6 millones de palestinos que viven en la diáspora, principalmente en Oriente Medio. Las estimaciones del número de descendientes de palestinos en Chile oscilan entre 450.000 y 500.000.

[4]

Palestinians in Chile (Arabic: فلسطينيو تشيلي) are believed to be the largest Palestinian community outside of the Arab world. There are around 6 million Palestinians living in diaspora, mainly in the Middle East. Estimates of the number of Palestinian descendants in Chile range from 450,000 to 500,000.

When I read your letter and your reflection on the colors of the landscapes, I remembered a myth that is heard here in Chile in relation to the magnitude of the Palestinian diaspora.

[4]

The usual question about why Chile. Once I was told that one of the reasons was the climate and the similarity in agriculture; in both places, cacti and tunas are harvested. Yesterday I ate the first tuna of the year that came from Tiltil. I google the distance between Al Makhrour and Tiltil: 13,225 km.

Mientras la comíamos, estábamos viendo las noticias nacionales. Toda la pantalla era roja y naranja. El fuego consume el territorio, transformando las casas en cenizas y escombros, y en mi mano, coponcito de los Andes, bordada de agujitas, agua del desierto.[5] Nuestras ciudades arden y en mi mano, hay un pequeño manantial, un cortafuegos natural.

Tuna corta fuegos. ¡Corten el fuego ya!

En Gaza, el agua de lluvia también pertenece a Israel. En Chile, el agua está privatizada desde hace décadas. Hoy nos llega otra noticia: desapareció el jardín botánico de Viña del Mar. Árboles de 200 años, una laguna con fauna, senderos en una selva valdiviana y preciosos eucaliptos. Todo calcinado.

Si tocas las tunas pueden dañarte la piel, pero guardan y protegen lo que nos da vida. Resistir y hacer daño parecen inseparables.

Tuna corta fuegos. ¡Corten el fuego ya!

En Gaza, el agua de lluvia también pertenece a Israel. En Chile, el agua está privatizada desde hace décadas. Hoy nos llega otra noticia: desapareció el jardín botánico de Viña del Mar. Árboles de 200 años, una laguna con fauna, senderos en una selva valdiviana y preciosos eucaliptos. Todo calcinado.

Si tocas las tunas pueden dañarte la piel, pero guardan y protegen lo que nos da vida. Resistir y hacer daño parecen inseparables.

[5]

Tacita de los Andes, bordada con agujas, agua del desierto. Frase de la Tuna Tunita del poeta Cayo Santos Huamán

[5] Little cup from the Andes, embroidered with needles, water from the desert. Phrase from Tuna Tunita from the poet Cayo Santos Huamán

While we were eating it, we were watching the local news. The whole screen was red and orange. The fire consumes the territory, transforming the houses into ashes and rubble, and in my hand, coponcito de los Andes, bordada de agujitas, agua del desiertot.[5]

Our cities burn and in my hand, there is a small spring, a natural firebreak.

Tuna corta fuegos. ¡Corten el fuego ya!

In Gaza, rainwater also belongs to Israel. In Chile, water has been privatized for decades. Another piece of news hits us: the botanical garden of Viña del Mar disappeared. 200-year-old trees, a lagoon with fauna, trails in a Valdivian jungle, and precious eucalyptus. All burned to ashes.

If you touch the tunas they can damage your skin, but they keep and protect that which gives us life. Resisting and pricking seem to be inseparable.

Tuna corta fuegos. ¡Corten el fuego ya!

In Gaza, rainwater also belongs to Israel. In Chile, water has been privatized for decades. Another piece of news hits us: the botanical garden of Viña del Mar disappeared. 200-year-old trees, a lagoon with fauna, trails in a Valdivian jungle, and precious eucalyptus. All burned to ashes.

If you touch the tunas they can damage your skin, but they keep and protect that which gives us life. Resisting and pricking seem to be inseparable.

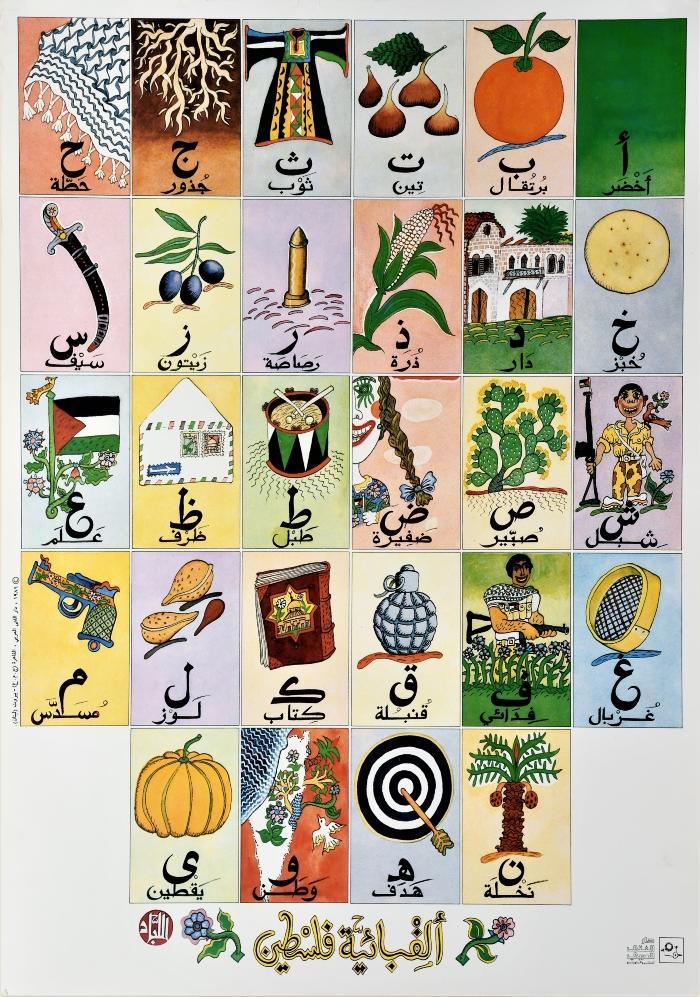

ES "El alfabeto palestino", cartel de Dar al-Fata al-Arabi, 1986 [6]

EN "The Palestinian Alphabet", a Poster by Dar al-Fata al-Arabi, 1986 [6]

[6] https://palarchive.org/index.php/Detail/objects/233948/lang/en_US

Estaba buscando en el palarchive (del museo palestino), y encontré este cartel del alfabeto palestno. Ahí se ve el dibujo de un cactus para ilustrar la letra “S” por “sabr” que en árabe significa paciencia o perseverancia y se han convertido en un símbolo de resiliencia para el pueblo palestino.

En Chile usamos la expresión estar como tuna, para decir que alguien está en buenas condiciones físicas, como si no le hubiera afectado el paso del tiempo.

¿Quién archiva el trabajo del archivador? En Jerusalén, visité un lugar llamado Khazaaen, donde Alaa Qaq, quien trabaja ahí, me abrió la puerta. “Khazaaen”, me explicó Alaa, “significa armarios, y eso es lo que tenemos”. Cada persona que contribuye tiene un armario para guardar su legado. Este material conserva la memoria colectiva de toda una comunidad, revelando diversos hechos históricos y alteraciones a lo largo de la historia social. El archivo, concebido como el agua, cambia para siempre el terreno que atraviesa, y Khazaaen es el cactus que actúa como cortafuegos natural, impidiendo que el paso del tiempo actúe como el fuego sobre la memoria, quemándolo todo. Esos armarios nos salvan de ese miedo al olvido.

En Chile usamos la expresión estar como tuna, para decir que alguien está en buenas condiciones físicas, como si no le hubiera afectado el paso del tiempo.

¿Quién archiva el trabajo del archivador? En Jerusalén, visité un lugar llamado Khazaaen, donde Alaa Qaq, quien trabaja ahí, me abrió la puerta. “Khazaaen”, me explicó Alaa, “significa armarios, y eso es lo que tenemos”. Cada persona que contribuye tiene un armario para guardar su legado. Este material conserva la memoria colectiva de toda una comunidad, revelando diversos hechos históricos y alteraciones a lo largo de la historia social. El archivo, concebido como el agua, cambia para siempre el terreno que atraviesa, y Khazaaen es el cactus que actúa como cortafuegos natural, impidiendo que el paso del tiempo actúe como el fuego sobre la memoria, quemándolo todo. Esos armarios nos salvan de ese miedo al olvido.

I was looking in the palarchive (of the Palestinian museum), and I found this poster of the Palestinian alphabet. There you see the drawing of a cactus to illustrate the letter "S" for "sabr" which in Arabic means patience or perseverance and has become a symbol of resilience for the Palestinian people.

In Chile we use the expression estar como tuna meaning be like a tuna, to say that someone is in good physical condition, as if they have not been affected by the passage of time.

Who archives the archivist's work? In Jerusalem, I visited a place called Khazaaen, where Alaa Qaq, who works there, opened the door for me. "Khazaaen," Alaa explained to me, "means closets, and that's what we have." Each person who contributes has a cabinet to store his or her legacy. This material preserves the collective memory of an entire community, revealing various historical events and alterations throughout social history. The archive, conceived as water, forever changes the terrain it crosses, and Khazaaen is the cactus that acts as a natural firewall, preventing the passage of time from acting like fire on memory, burning everything. These cabinets save us from that fear of forgetting.

In Chile we use the expression estar como tuna meaning be like a tuna, to say that someone is in good physical condition, as if they have not been affected by the passage of time.

Who archives the archivist's work? In Jerusalem, I visited a place called Khazaaen, where Alaa Qaq, who works there, opened the door for me. "Khazaaen," Alaa explained to me, "means closets, and that's what we have." Each person who contributes has a cabinet to store his or her legacy. This material preserves the collective memory of an entire community, revealing various historical events and alterations throughout social history. The archive, conceived as water, forever changes the terrain it crosses, and Khazaaen is the cactus that acts as a natural firewall, preventing the passage of time from acting like fire on memory, burning everything. These cabinets save us from that fear of forgetting.

Carta #5: camara en mano en Palestina 2019

Hola amiga

Esta es mi ultima carta:

27 de marzo de 2024,

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires

Hola amiga

Esta es mi ultima carta:

Letter #5: my handy archives in Palestine 2019

Hi my friend!

This is my last letter:

March 27, 2024,

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Hi my friend!

This is my last letter:

Te mando un abrazo que cruce el mar Atlántico

Maia

Maia

I send you a hug that crosses the Atlantic Sea…

Mai

Mai

Carta #6: Agua Santa

Hola amiga,

Aquí está mi última carta. Archivos de video de cuando nos conocimos. Espero que nos volvamos a ver pronto. Ha pasado demasiado tiempo, demasiada agua bajo el puente.

25 de abril de 2024,

Amsterdam, Países Bajos

Amsterdam, Países Bajos

Hola amiga,

Aquí está mi última carta. Archivos de video de cuando nos conocimos. Espero que nos volvamos a ver pronto. Ha pasado demasiado tiempo, demasiada agua bajo el puente.

Letter #6: Agua Santa

Hola amiga,

Here is my last letter. Video archives from the time we met. I hope we meet again soon. It has been way too long, way too much water under the bridge.

April 25, 2024

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Hola amiga,

Here is my last letter. Video archives from the time we met. I hope we meet again soon. It has been way too long, way too much water under the bridge.

Maia Gattás Vargas

Artista visual, audiovisual, docente universitaria e investigadora.

Doctora en Artes. Línea de formación en Arte Contemporáneo Latinoamericano (UNLP).

Se graduó como licenciada en Ciencias de la Comunicación y Profesora en enseñanza media y terciaria (UBA).

Trabaja como becaria posdoctoral CONICET y como docente de la materia Teorías de los Medios y de la Cultura en la Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Co-organizó la residencia Laboratorio isla Victoria: Arte/Ciencia/Naturaleza en Isla Victoria del lago Nahuel Huapi (2019, 2020 y 2021).

En 2019 fue becada para cursar el Programa de cine de la Universidad Di Tella y en 2023 participó del Talents Buenos Aires organizado por el Festival Bafici y la FUC.

En 2022 publicó su primer libro de artista Diario de exploración al territorio del color, editado por la Biblioteca Popular Astra de Comodoro Rivadavia, dentro de su colección de Arte Contemporáneo Imai.

Su primer largometraje documental Viento del este tuvo su estreno nacional en agosto de 2023 en el Festival Doc Buenos Aires y su estreno internacional en el Jihlava IDFF en República Checa, donde ganó el premio Original Approach.

Ha expuesto sus obras visuales y audiovisuales en distintas provincias de la Argentina (Río Negro, Buenos Aires, Tierra del Fuego, Córdoba, Santa Fé y Neuquén), y en países como Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, Canadá, República Checa.

Participó de varias residencias artísticas, entre ellas: Residencia artística de Parques Nacionales, organizada por el ex Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación, agosto 2023; Casa Tres Patios, Medellín, Colombia, abril-mayo 2021; Barda del desierto, marzo 2023; Residencia virtual Rumor en Cordillera galería, Chile, 2020; Residencia Federal Panal 361-CFI. Buenos Aires, 2018.

Ha obtenido los premios: Bienal de Arte Joven de Buenos Aires, 2019; Beca de Creación del Fondo Nacional de las Artes, 2022. Becar Cultura del Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación, para asistir al IV Encuentro Iberoamericano de Trabajo, Arte y Economía en la galería Arte Actual de FLACSO, Quito, Ecuador. 2016.

Su obra artística aborda las relaciones entre imágenes, ciencia, paisaje, naturaleza e historia colonial. Realiza instalaciones de carácter archivístico que combinan video, collage, fotografías, documentos y escritura.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎ ︎

Francisca Khamis Giacoman

Francisca Khamis Giacoman es una artista visual y diseñadora con base en Ámsterdam. A través de performances, instalaciones y obras audiovisuales, evoca historias de migración y las despliega en los límites de la ficción y la materialidad. Su investigación aborda el lenguaje, la producción de conocimiento y la accesibilidad a través de la circulación narrativa, centrándose en diferentes formas de (re)conocernos a nosotros mismos y a los demás.

Involucrada activamente en proyectos autoorganizados, Francisca fundó el "Museo del Perro * Honden Museum" en Ámsterdam (2023), co-fundó "Ediciones Rocas Shop" Cooperative Publishing House en Santiago (2017-22), C.I.A (Centro de Investigación Artístico) en Santiago (2013-15) y Espacio Estamos Bien, una cooperativa artística en Ámsterdam que organiza encuentros, publicaciones y exhibiciones. Actualmente, lidera el desarrollo de una iniciativa de apoyo para estudiantes no europeos en el Sandberg Instituut y la Gerrit Rietveld Academie.

Ha expuesto en Rozenstraat, Amsterdam; Extracity, Antwerp; Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam; Kunstverein, Amsterdam; PuntWG, Amsterdam; Stroom, The Hague; de Apple, Amsterdam; BPA Raum, Berlin; Stadium, Berlin; Bibliotek, London; Gold+ Beton, Cologne, entre otros.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎ ︎

Maia Gattás Vargas

Visual artist, audiovisual creator, university lecturer, and researcher.

PhD in Arts. Specialized in Latin American Contemporary Art (Universidad Nacional de La Plata).

She graduated with a degree in Communication Sciences and as a secondary and tertiary education professor (UBA).

She works as a postdoctoral fellow at CONICET and as a professor of Media and Culture Theories at Universidad de Buenos Aires.

In 2019 she received a scholarship to attend the Di Tella University Film Programme and in 2023 she participated in Talents Buenos Aires organised by the Bafici Festival and the FUC.

In 2022, she published her first artist book Diario de exploración al territorio del color, edited by Biblioteca Popular Astra de Comodoro Rivadavia, as part of its Contemporary Art Imai collection.

Her first feature-length documentary Viento del este (East wind) premiered nationally in August 2023 at the Doc Buenos Aires Festival and internationally at the Jihlava IDFF in the Czech Republic, where it won the Original Approach award.

She has exhibited her visual and audiovisual works in different provinces of Argentina (Río Negro, Buenos Aires, Tierra del Fuego, Córdoba, Santa Fé and Neuquén), and in countries such as Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, Canadá, and the Czech Republic.

She participated in several artistic residencies, among them: National Parks Artistic Residency, organised by the former Ministry of Culture of the Nation, August 2023; Casa Tres Patios, Medellín, Colombia, April-May 2021; Barda del desierto, March 2023; Rumor virtual residency in Cordillera gallery, Chile, 2020; Federal Residency Panal 361-CFI. Buenos Aires, 2018.

She has been awarded the following prizes: Bienal de Arte Joven de Buenos Aires, 2019; Beca de Creación del Fondo Nacional de las Artes, 2022. Becar Cultura of the National Ministry of Culture, to attend the IV Encuentro Iberoamericano de Trabajo, Arte y Economía at the gallery Arte Actual of FLACSO, Quito, Ecuador. 2016.

Her artistic work explores the relationships between images, science, landscape, nature, and colonial history. She creates archival installations combining video, collage, photographs, documents, and writing.

︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎

Francisca Khamis Giacoman

Francisca Khamis Giacoman is a visual artist and designer based in Amsterdam. Through performances, installations, and audiovisual works, she recalls stories of migration and unfolds them at the boundaries of fiction and materiality. Her research touches upon language, knowledge production, and accessibility through narrative circulation, focusing on different ways of (re)membering ourselves and others.

Actively involved in self-organized projects, Francisca co-founded the “Museo del Perro * Honden Museum” in Amsterdam (2023), “Ediciones Rocas Shop” Cooperative Publishing House in Santiago (2017-22), C.I.A (Centro de Investigación Artístico) in Santiago (2013-15) and Espacio Estamos Bien, an art cooperative in Amsterdam that curates gatherings, publications, and exhibitions. Currently, she leads the development of a support initiative for non-European students at the Sandberg Instituut and Gerrit Rietveld Academie.

She has exhibited at Rozenstraat, Amsterdam; Extracity, Antwerp; Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam; Kunstverein, Amsterdam; PuntWG, Amsterdam; Stroom, The Hague; and Stadium, Berlin; Bibliotek, London; Gold+ Beton, Cologne, among others.

︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎

About the Sea, 2007, Sobhi al-Zobaidi'

About the Sea, 2007, Sobhi al-Zobaidi'