Alia Mossallam

Children of a

non-aligned future

Coverage of the second Non-Alliance conference in Cairo through children’s Comic books, and the growing spirit of the Tri-continental

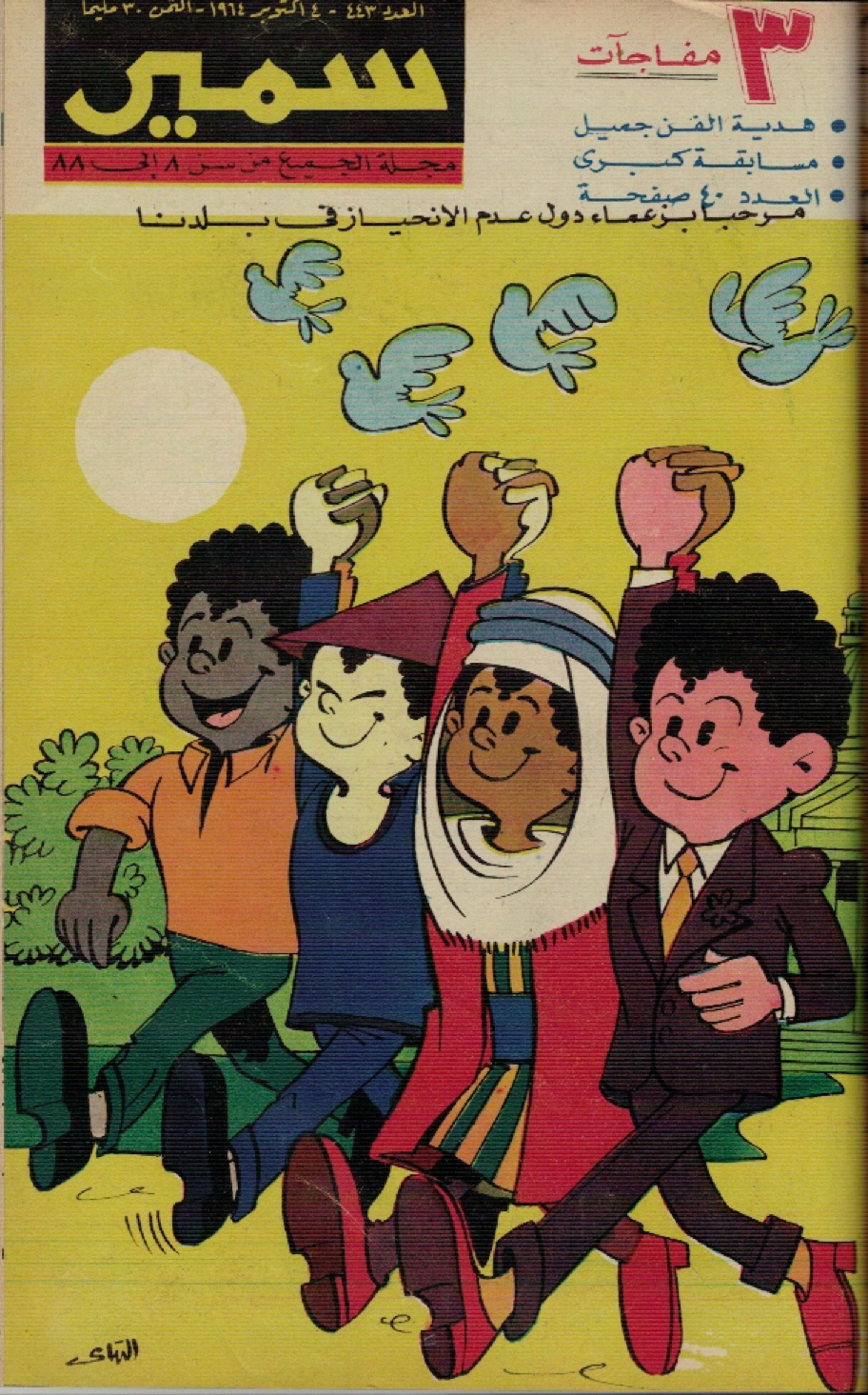

On the cover of this issue of the Egyptian children’s magazine “Samir”, in October 1964, are four versions of Samir, hands held in unison as they march into a future we can’t see. They champion peace (with the pigeons fluttering above them) on the occasion of the second Non-alliance summit in Cairo. The versions of Samir could represent children from the three continents, Latin America, North and Subsaharan Africa and Asia. Alternatively, one may imagine Abdelnasser, Ben Bella, Sukarno, and Nkrumah…or their children. It is clearly left to the reader’s imagination, in a time where the future was being reconstrued and imagined along new political fault-lines based on anti-imperial movements and new alliances.

This cover is typical to many of the children’s comic books in the 1960s which were instrumentalized to ‘trickle down’ the new political ideas emerging from Pan Arab (socialist) nationalism, Afro-Asian solidarity movements, the non-alliance movements and the Tri-continental movement. The future was a possibility that revolved around the establishment of a particular brand of peace (a peace based on justice, as we will read further on). Most importantly however, and what I intend to explore with this essay is the centrality of the children, as mediums between this present and its future, or elements of this futurism. In this essay, I look at the strategies of communicating these ideas to children, visually and politically. I believe children’s literature of this time boiled the ideas down to their very core and principal components, rather than simplifying them for a child’s understanding. The comics thus archive the core vocabulary and elements of the moments’ ideology, as well as the strategies to communicate it to children. They constitute an archive of the visual construction of political imaginaries in the intimate spaces of childhood.

My interest in children’s magazines from the 1960s, started with my attempt to understand how the Aswan High Dam was communicated to children; how it became - as a scientific and technological project - a practical manifestation of the ideology of the time. The science of the Dam was communicated as a wonder, a kind of ‘materialist magic’, that was achievable thanks to the 1952 revolution. To explain the Dam was to explain its science, couched in all the events that made it possible. This included the nationalisation of the Suez Canal, the (anti-imperial) guerrilla warfare against the tripartite aggression as a result of it, and the anti-colonial liberation war for Algeria, for example. Furthermore, the Dam’s wider significance is the struggle for economic independence and non-alliance with cold war powers, that other members of the non-alignment movement who built Dams also celebrated (Syria, India, Ghana and Yoguslavia included). The High Dam was also contextualised in the struggle for the liberation of Palestine, by narrativizing it as a tool for economic liberation and prosperity, that would enable the development of the Egyptian and larger Arab ummah in preparation for the ultimate war for the liberation of Palestine.

This cover is typical to many of the children’s comic books in the 1960s which were instrumentalized to ‘trickle down’ the new political ideas emerging from Pan Arab (socialist) nationalism, Afro-Asian solidarity movements, the non-alliance movements and the Tri-continental movement. The future was a possibility that revolved around the establishment of a particular brand of peace (a peace based on justice, as we will read further on). Most importantly however, and what I intend to explore with this essay is the centrality of the children, as mediums between this present and its future, or elements of this futurism. In this essay, I look at the strategies of communicating these ideas to children, visually and politically. I believe children’s literature of this time boiled the ideas down to their very core and principal components, rather than simplifying them for a child’s understanding. The comics thus archive the core vocabulary and elements of the moments’ ideology, as well as the strategies to communicate it to children. They constitute an archive of the visual construction of political imaginaries in the intimate spaces of childhood.

My interest in children’s magazines from the 1960s, started with my attempt to understand how the Aswan High Dam was communicated to children; how it became - as a scientific and technological project - a practical manifestation of the ideology of the time. The science of the Dam was communicated as a wonder, a kind of ‘materialist magic’, that was achievable thanks to the 1952 revolution. To explain the Dam was to explain its science, couched in all the events that made it possible. This included the nationalisation of the Suez Canal, the (anti-imperial) guerrilla warfare against the tripartite aggression as a result of it, and the anti-colonial liberation war for Algeria, for example. Furthermore, the Dam’s wider significance is the struggle for economic independence and non-alliance with cold war powers, that other members of the non-alignment movement who built Dams also celebrated (Syria, India, Ghana and Yoguslavia included). The High Dam was also contextualised in the struggle for the liberation of Palestine, by narrativizing it as a tool for economic liberation and prosperity, that would enable the development of the Egyptian and larger Arab ummah in preparation for the ultimate war for the liberation of Palestine.

1. Kirill Chunikin’s term for describing how electricity was depicted in Soviet children’s books as “a socialist technological wonder/miracle”. See Chunikin, Kirill, “Soviet Children and Electric Power” in Balina, Marina, and Serguei Alex Oushakine, eds. Pedagogy of Images: Depicting Communism for Children. University of Toronto Press, 2021: Page 278

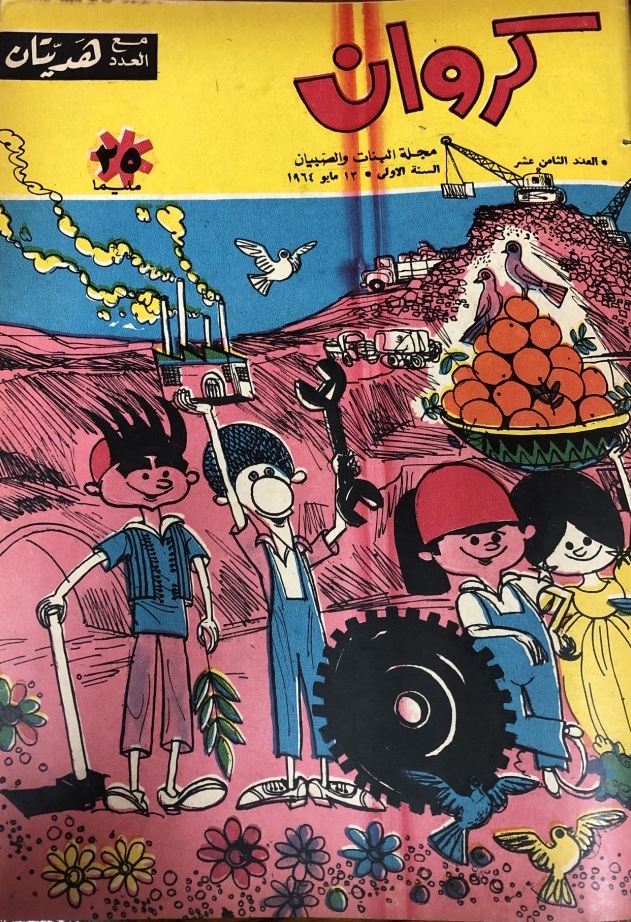

In this next image of the cover of Al-Karawan for instance, the elements of Arab socialism (the worker, the student and the peasant), the nationalised factories, the oranges of Yaffa, and the pigeons, are on this 1964 issue about the High Dam. The colours pink and yellow (recurrent in this magazine) depart from the red/black/green palette which is typical to the political iconography/vocabulary of this era, while indicating this constant euphoria.

The scenes are always a collage of sorts, of realistic children against unrealistic but materialising realities. In most of these issues, the High Dam was depicted in full, (or the children were given models of the Dam in pieces with every magazine edition to construct) before its actual construction was fully realised.

Larissa Rudova refers to this as ‘photo montage’ of ‘romanticised industry,’ collaging images of industry against nature, against people, against text and ideological ideas or symbols (what she refers to as educational soviet propaganda). The collage of ideology against industry makes for a scientific or objective (thus unquestionable) story, and the fantasy makes it a dream.

The scenes are always a collage of sorts, of realistic children against unrealistic but materialising realities. In most of these issues, the High Dam was depicted in full, (or the children were given models of the Dam in pieces with every magazine edition to construct) before its actual construction was fully realised.

Larissa Rudova refers to this as ‘photo montage’ of ‘romanticised industry,’ collaging images of industry against nature, against people, against text and ideological ideas or symbols (what she refers to as educational soviet propaganda). The collage of ideology against industry makes for a scientific or objective (thus unquestionable) story, and the fantasy makes it a dream.

2. Rudova, Larissa. "From nature to “second nature” and back." In Balina, Marina and Serguei Alex Oushakine, eds. The Pedagogy of Images: Depicting Communism for Children ,2021: 217.

In this essay, I look specifically at the Samir issue of October 1964, and the kind of montage that was used to depict the non-aligned movement. How it was presented to children through various texts, images, comics, stories, and other materials. In Oushakine and Balina’s edited volume “Pedagogy of Images”, they highlight how communism in the Soviet Union’s 1920s had major pedagogical ambitions of building a new society, which is tightly linked with creating new forms of social imagination and new vocabularies of shared images as to how that society looked, or what constituted it. Studying these comics, thus gives insight into the ways through which these societies “emerged, existed and vanished.” For my work, these comics became a way to understand how political ideas, were communicated to children in order to shape and form the imagined community they believed they were part of and the imagined future to which they would contribute. They also give us a preview into the workings of hegemony, how these ideas were communicated as ‘common sense’ and through children’s feedback, we can trace how they were ascribing to them.

3. “Introduction. Primers in Societ Modernity: Depicting communism for Children in Early Soviet Russia” In Balina, Marina and Serguei Alex Oushakine, eds. The Pedagogy of Images: Depicting Communism for Children. University of Toronto Press, 2021. P 41

A magazine for all; big and small

Whether it was Samir (established in 1956), Al Karawan (1964) or Sindbad (1962), the magazines were tailored to children of all ages (starting around 8) and tailored to different levels of literacy. The magazines were riddled with comics, all with high elements of comic relief and suspense and based in different contexts- fictive (scientific) futures, ancient histories, exotic jungles, and with elements of popular culture. But they also included coverage of particular events (the magazines were themed), such as the Arab or African Summits, the Tokyo Olympics, or in this particular issue the 2nd meeting of the Non-aligned movement, which convened in Cairo in October 1964.

Aside from the coverage of the specific theme, each magazine included an extract from a novel by a famous (usually socialist realist) novelist, as well as a biography of this novelist, an interview with a politician, member of government or literary figure (conducted by children). It also included an “Ask mama Lubna” section, which was a Q&A with the editor, inviting the children to contribute to the magazine’s content with questions or ideas. Most issues also included a board-game or some sort of crafts that related to the subject matter. Cut outs where included for children to scissor and construct, to engage more deeply and playfully with the topic of the day. Book reviews, film reviews as well as political songs or television segments were also core elements of the magazine.

4. Including Yahia Haqqi, Ahmed Bahaa El din, Saad el Din Wahba, and even when they were novelist of a classical genre (such as Tawfiq el Hakim, or Abbas el Aqqad, their biographies were narritivized as their rise to fame as unlikely heroes due to poverty or their hard work at school where their writing first attracted attention. The biographic style was always pedagogical, as if instructed that writing the world in this style can start at a very young age. Or that the world and success belonged to the working class.

This combination of approaches to communicate politics to children is very similar to children’s comics in Yugoslavia in the 1960s. The purpose of such publications, and Zmaj magazine in particular was to produce ideological content in a way that was “simple, repeatable and recognisable in graphic images,” to become “a vehicle of ideology, an object of affection and a product of labour.”

5.

“Introduction. Primers in Society Modernity: Depicting communism for Children in Early Soviet Russia” In Balina, Marina and Serguei Alex Oushakine, eds. The Pedagogy of Images: Depicting Communism for Children. University of Toronto Press, 2021. P 39

In her article on the children’s Yoguslav magazine “Zmaj”, Sanja Radak describes how these magazines were built on the theory that early political learning is enduring over an adult’s lifetime. This form of political pedagogy was also present in simple lessons related to “creating the image of the socialist citizen and the non-aligned child as the object of reproduction of Yugoslav socialism.” This was reiterated in comics whose characters sacrificed winning competitions over helping others to the finish-line. The emphasis on ethics in hunting, unlikely heroes, and the fight against all mythical evils.

6. Lazarević Radak, Sanja. “The Non-Aligned Child: the Magazine Zmaj and the Political Socialization in Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1966 – 1971).” Sociocultural Dimensions of Childhood, 2020.

“Half the world’s inhabitants gather in Cairo!”

The main article in this issue is a depiction of the conference, its members, the main issues discussed, and the principles of the Non-Aligned movement.

The text starts with a quote by Abdelnasser, “The picture of this conference is, I believe, the closest to a picture of a peace assembly. Therefore, it is important in my opinion that peace – peace that is based upon justice – becomes the biggest goal of this conference…”. The rest of the article quotes Abdelnasser, on the meaning of “non-alignment”: establishing policies based on our own priorities and not those of the more powerful nations whose alliance or support we may need. The article lists the 59 countries (“half of the world in Cairo!”) while indicating how many more there are than the 24 nations that gathered for the first non-alliance conference in Belgrade in 1961. It indicates the main issues covered by the conference, namely studying the international political scene in general, colonialism and countries still struggling for their independence, racial segregation, and stopping nuclear trials. The conference’s resolutions, including letters to Kennedy and Khrushev calling for this nuanced understanding of peace, and indicating the conditions for non-alliance.

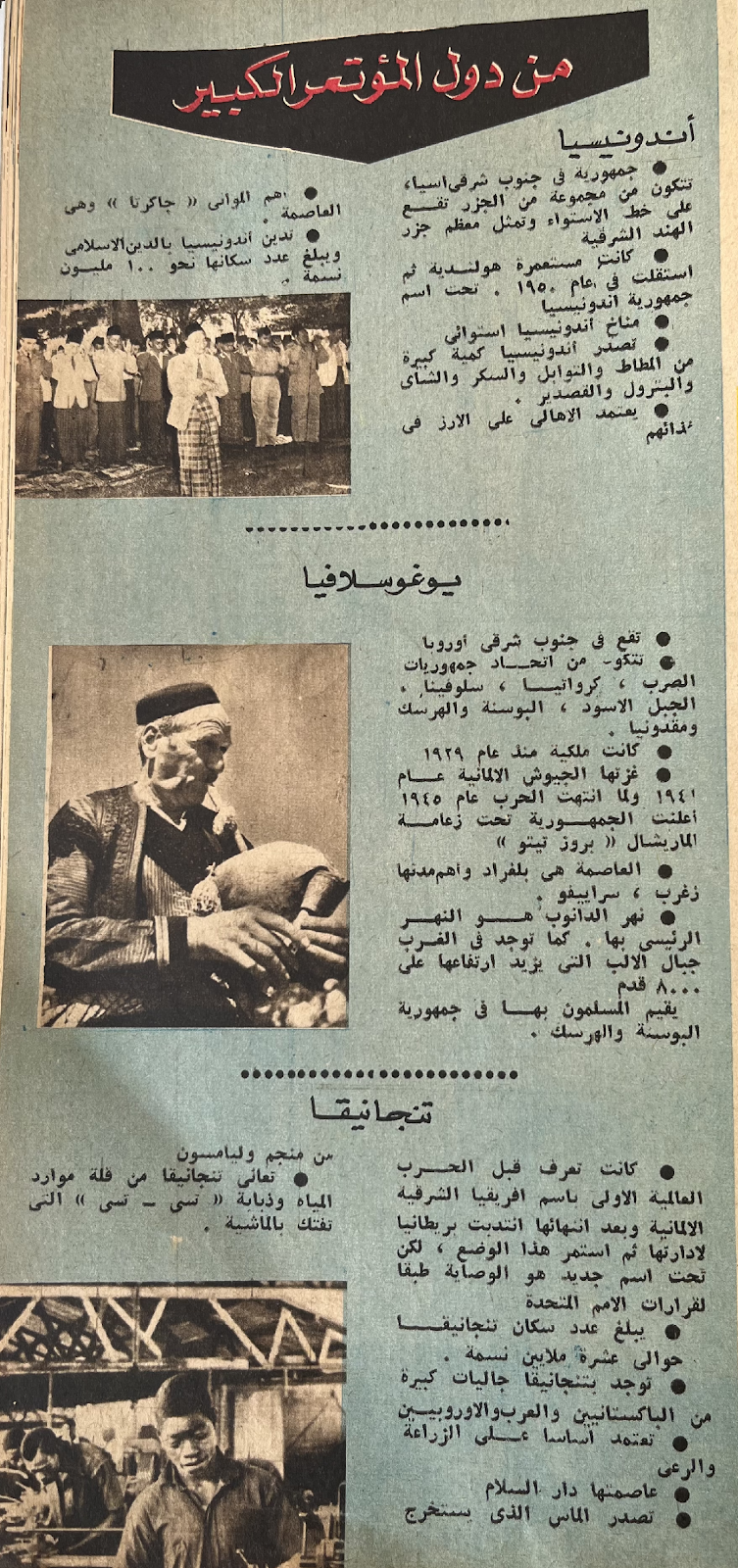

The section extends with short segments about some of the member countries of the non-aligned movement. In this case, it was Indonesia, Yugoslavia, Tenganyika (soon to become Tanzania), Cuba and Cameron, indicating in bullet points each country’s respective geography, economy, languages spoken and their anti-colonial struggle.

In this section, an expansive sense of the world is encountered through both geographic and political maps based on elements of shared struggles, encouraging a familiarity and belonging to a larger world. The information is almost always political, including elements about colonialism and liberation struggles in the introduction to any country. Information is provided in a way that is memorable, relatable (such as biographies of political leaders’ childhoods) as well as ‘repeatable’ in the form of short stories, or songs.

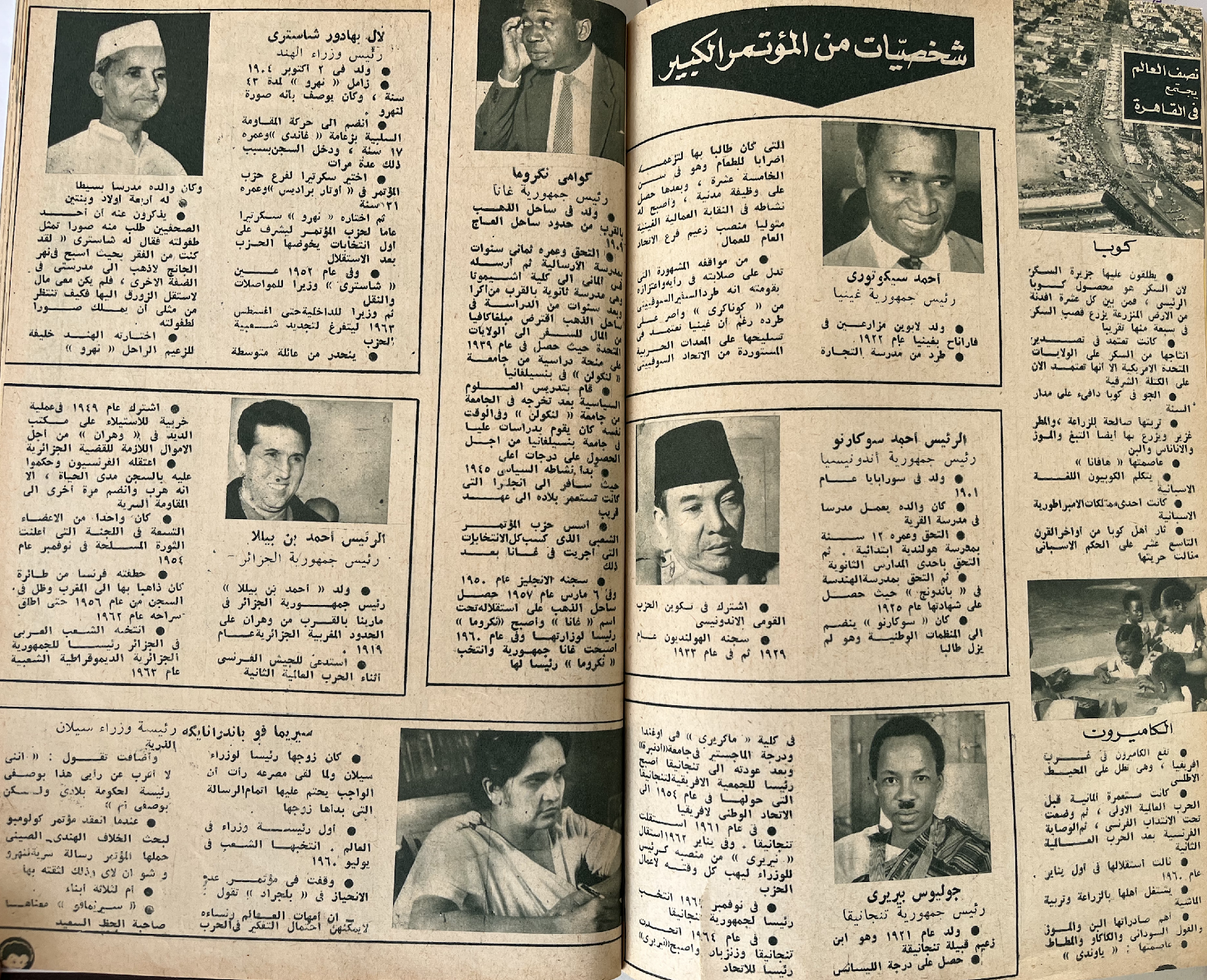

The biographies of selected ‘characters’ from the conference, including Ahmed Sékou Touré of Guinea, Ahmed Sukarno of Indonesia, Julius Nyerere of Tanganyika, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria, Lal Bahadur Shastri of India, and Sirimavo Bandaranaike. The biographies are constructed in ways the children can relate to, personally. This includes where and how they went to school for instance, but also emphasis on their coming from modest backgrounds whenever this was the case, and their anti-colonial struggles or sacrifices for their political ideas, which usually led to their brief imprisonment. This style of biography writing is typical to the magazine where all literary and political figures that are introduced to have had an unlikely becoming, one that any child could clearly find themselves in before they aspire to greatness. All except for Sirimavo Bandaranaike (or perhaps in a different way), who is modelled as a wife who succeeded her husband, and a woman who understands the values of peace as a mother, regardless of her own political struggles. Her ‘identity’ is sexualised primarily as a mother and wife. Her political position is defined as her having succeeded her husband, and her championing peace related to her understanding its importance as a mother, downplaying her own ideological position or political convictions.

The biographies of selected ‘characters’ from the conference, including Ahmed Sékou Touré of Guinea, Ahmed Sukarno of Indonesia, Julius Nyerere of Tanganyika, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria, Lal Bahadur Shastri of India, and Sirimavo Bandaranaike. The biographies are constructed in ways the children can relate to, personally. This includes where and how they went to school for instance, but also emphasis on their coming from modest backgrounds whenever this was the case, and their anti-colonial struggles or sacrifices for their political ideas, which usually led to their brief imprisonment. This style of biography writing is typical to the magazine where all literary and political figures that are introduced to have had an unlikely becoming, one that any child could clearly find themselves in before they aspire to greatness. All except for Sirimavo Bandaranaike (or perhaps in a different way), who is modelled as a wife who succeeded her husband, and a woman who understands the values of peace as a mother, regardless of her own political struggles. Her ‘identity’ is sexualised primarily as a mother and wife. Her political position is defined as her having succeeded her husband, and her championing peace related to her understanding its importance as a mother, downplaying her own ideological position or political convictions.

A Non-Aligned world, your oyster

The techniques used by the magazine intended to help children imagine themselves contributing to the new worlds (rather than just consume and repeat them) are quite progressive, or pedagogic, in comparison to the superficial state propaganda of current times. It includes various sections that serve the development of an imagination of how and what aspects of their lives could lead to their politicisation or radicalisation, revolutionary ideas which they could easily understand and relate to, as well as informative histories of colonial and imperial struggle delivered in ways they could understand and imagine. The magazine presented a world that was evolving and growing (the proceedings of the conferences showed how the ideas of alliances were developing and a notion like peace was becoming more and more nuanced). There was action everywhere in the world and revolutionary changes and struggles were enacted by people who were children ‘just like us’, and in countries ‘just like ours’. To be an Egyptian child during this period meant to the be part of the key moments of alliance, on the level of the Third World, the African continent, the Arab world and soon, the tri-continental. The message to children was: there was a clear place for you in a growing world, and a vivid place for it in your imagination.

The section where children write to “mama Lubna” (the editor, Nutayla Rashid) illustrate that readers come from all over Egypt but also Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Bahrain, Iraq, among other countries.

The gendering of revolutionary ideas in the magazine however, left much to be desired. Segments dedicated to girls focus on their body image, and their social behaviour. Their encouraged ambitions are literary and include vocations such as teachers and nurses and social workers, but rarely engineers or scientists.

Although it would be too simplistic to categorize the magazines as propaganda, the more regressive political ideas in relation to gender, or critiques of the extent of independence of non-alliance countries from the cold war axes, would have been difficult to critique. The tight montage provides layers of engagement with the existing ‘revolutionary truths’. Disengagement or critique must have required a degree of disinterest.

These magazines and others, provide a valuable archive to explore both the visual vocabulary of this ideological moment, as well as a deeper understanding of the core elements that were to be communicated to children and how that was the case. Between this period and say, the Dar al-Fatta al ‘Arabi children’s literature in the decades to come, the archive is a both a history and resource as to what political pedagogy could mean and how it can be offered to inform children whilst still encouraging critical engagement.

Given the growing emphasis on peace being a result of struggle, and possible only after achieving justice, the growing place of Algerian guerrilla warfare in the centrality of struggle, it would be interesting to follow these magazines further and trace the departure from the ideas of the non-alliance movement, to the more radical and uncompromising struggle for liberation that came with the Tri-continental conference, two years later. Even more interesting would be to get past the interface of these magazines (perhaps in the folds of the curated correspondences between children and magazine editors), to trace how their own ideas may have been developing in relation to an understanding of revolutionary struggle.

Alia Mossallam

Alia Mossallam is a cultural historian interested in songs that tell stories and stories that tell of popular struggles behind the better-known events that shape world history.

She is currently a EUME post-doctoral fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in Berlin where she is writing a book on the visual and musical archiving practices of the builders of the Aswan High Dam and the Nubian communities displaced by it. She is also a visiting scholar at Humboldt University’s Lautarchiv exploring the experiences of Egyptian, Tunisian and Algerian workers and subalterns on the fronts of World War I (and resulting revolts in their regions in 1918) through songs that capture these experiences.

Some of her writings can be found in The Journal of Water History, The History Workshop Journal, Jadaliyya, Ma’azif, Bidayat and Mada Masr. In producing her research in different formats, she has tried her hand at playwriting with Hassan el-Geretly and Laila Soliman and written “Rawi” in the long-form nonfiction platform 60-pages.

An experimentative pedagogue, she founded the site-specific public history project “Ihky ya Tarikh”, and taught at the American University in Cairo, Cairo Institute for Liberal Arts and Sciences, and the Freie Universität in Berlin.

︎ ︎