Anaïs Farine &

Nathalie Rosa Bucher

Nathalie Rosa Bucher

Correspondent Quests:

Traces of PFLP cinema in Beirut

Beirut, 3 February 2024

My dear Anaïs,

1.

In memory of Lokman Slim. And Nevine Marchiset-Bulos.

2.The Baalbeck Studios (1963-1994) institutional archive provides a fascinating paper trail to over 100 feature film productions, gives insight into the making of these films as well as newsreels. It includes exchanges with commercial directors and internal work sheets from the various departments (equipment unit, administration including financial matters, management and staff, recording studio, editing and laboratory).

2.The Baalbeck Studios (1963-1994) institutional archive provides a fascinating paper trail to over 100 feature film productions, gives insight into the making of these films as well as newsreels. It includes exchanges with commercial directors and internal work sheets from the various departments (equipment unit, administration including financial matters, management and staff, recording studio, editing and laboratory).

Wrapping up years of work on three vast archival collections, including Baalbeck Studios, last month, my thoughts retraced the ghosts and (unsung) heroes, visionaries and revolutionaries that featured in it.1 When I first “met” the Baalbeck Studios paper archive 2, I was barely able to move! The shelves on the walls were filled with old Leitz and Elba folders, in the centre were large boxes piled up high.

I didn’t know precisely what Baalbeck Studios stood for nor what I’d find!

Initially, I organised the folders, paper files, notebooks, booklets and loose documents in the boxes. I created detailed inventories for a multitude of objects and connections with ghosts and protagonists, such as, musicians, filmmakers, producers, actors, commercial directors, suppliers – and most significantly a few of the 120 individuals I found to have worked anything between a few months and four decades at Baalbeck Studios – or their families.

Of the journalists and scholars who came over the years, asking for this or that, you were the only “repeat offender”, if I am not mistaken…

What did you expect when you first came to my office, filled with the memories of the who’s who of Arab filmmakers and musicians of the past sixty years, in 2020? What were you hoping to find?

I didn’t know precisely what Baalbeck Studios stood for nor what I’d find!

Initially, I organised the folders, paper files, notebooks, booklets and loose documents in the boxes. I created detailed inventories for a multitude of objects and connections with ghosts and protagonists, such as, musicians, filmmakers, producers, actors, commercial directors, suppliers – and most significantly a few of the 120 individuals I found to have worked anything between a few months and four decades at Baalbeck Studios – or their families.

Of the journalists and scholars who came over the years, asking for this or that, you were the only “repeat offender”, if I am not mistaken…

What did you expect when you first came to my office, filled with the memories of the who’s who of Arab filmmakers and musicians of the past sixty years, in 2020? What were you hoping to find?

Beirut, 5 February 2024

Dear Nathalie,

While I very much enjoyed being called a “repeat offender”, your letter made me realise how slow I had actually been to come knocking at your door. Indeed, no less than six months passed between our first meeting in Tripoli and my first visit to your office in Badaro. And it took me one more year before conducting research in the Ghobeiry archives at UMAM’s main office, where I found this beautiful portrait of Iraqi filmmaker Kassem Hawal published in Al-Balagh.

Before visiting you, I had heard that several pieces of correspondence between the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and Baalbeck Studios were preserved at UMAM. This was exciting. And enigmatic.

I remember that one note, sent by the PFLP to Baalbeck Studios caught my attention. This note is reproduced in the publication About Baalbeck Studios and Other Lebanese Sites of Memory (2013) and says:

“Attention Baalbeck Studios. Please provide us, on our responsibility, a 16mm camera and sound system [with which] to film the funeral of martyr Ghassan Kanafani (ص ٢٦).”

3.

Anaïs Farine, « The Making of Arab Alternative Cinema and its Audiences: Babelsberg, Beirut, Damascus, Leipzig », 31/08/23 :

https://oib.hypotheses.org/1539

It is very likely that this camera has been used to shoot scenes appearing in Ghassan Kanafani, A Word... A Gun by PFLP filmmaker Kassem Hawal (غسان كنفاني... الكلمة البندقية,1973) that was screened at the Arab Cultural Club (al-Nadi al-Thaqafi al-Arabi) in February 1973. Just as his previous film Nahr el Bared (1971), this film was edited by Saheb Haddad, an Iraqi who worked for Baalbeck Studios at the time as you once explained to me. In the archive of movie posters and film related material collector Abboudi Bou Jaoude that I have intimate knowledge of, I have been reading Al-Hadaf issues and encountered this certificate mentioning Hawal's film participating at the 1971 International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film. It was the first time a Palestinian delegation participated in this Festival. As other journals gathered by Bou Jaoude reveal, the Leipzig Festival played a decisive role in giving international exposure and recognition to PFLP films and to the ‘Arab Alternative Cinema’ in general.3

![Fig. 2 Al-Hadaf, N°131, 18/12/1971 (Courtesy of Abboudi Bou Jaoude)]()

Coming with this knowledge, I wanted to know more about the archives you were working on, specifically. What else was in there?

Driven by the word “correspondence” used by UMAM in this publication – a word to which I am conferring quite a romantic definition, I must confess – I was hoping to find long letters preserving the memory of ongoing conversations and relations between individuals on both the PFLP’s and Baalbeck Studios’ side.

Coming with this knowledge, I wanted to know more about the archives you were working on, specifically. What else was in there?

Driven by the word “correspondence” used by UMAM in this publication – a word to which I am conferring quite a romantic definition, I must confess – I was hoping to find long letters preserving the memory of ongoing conversations and relations between individuals on both the PFLP’s and Baalbeck Studios’ side.

4.

See: “Machine nécrophoniques” by Philippe Baudoin, in Le Royaume de l'au-delà, Thomas A.Edison, ed. Jérôme Millon, 2015.

Maybe the correspondence between us duplicates a previous connection with ghosts…4

In his Letters to Milena, Franz Kafka compares epistolary writing with “an intercourse with ghosts” (1922). A writer deeply in love at the time, Kafka deplores: “One can think about someone far away and one can hold on to someone nearby; everything else is beyond human power.” Having been lost or destroyed, Milena's letters are not reproduced in the book, leaving us with the impression that he is really corresponding with an absence.

Your intimacy with the Studio Baalbeck collection allows you to recognise the handwritings and to start looking for the voices of the absent ones.

Who are the addressees of the PFLP notes that you were capable of identifying?

Do you think that Badie Bulos, the Palestinian businessman who founded Baalbeck Studios, was himself in touch with the PFLP filmmakers such as Kassem Hawal?

In his Letters to Milena, Franz Kafka compares epistolary writing with “an intercourse with ghosts” (1922). A writer deeply in love at the time, Kafka deplores: “One can think about someone far away and one can hold on to someone nearby; everything else is beyond human power.” Having been lost or destroyed, Milena's letters are not reproduced in the book, leaving us with the impression that he is really corresponding with an absence.

Your intimacy with the Studio Baalbeck collection allows you to recognise the handwritings and to start looking for the voices of the absent ones.

Who are the addressees of the PFLP notes that you were capable of identifying?

Do you think that Badie Bulos, the Palestinian businessman who founded Baalbeck Studios, was himself in touch with the PFLP filmmakers such as Kassem Hawal?

Tripoli, 5 February 2024

Dear Anaïs,

Thank you for the picture of dapper, corduroy-clad Kassem! As you certainly know, he filmed considerable parts of his adaptation of Kanafani’s Return to Haifa here in Tripoli, assisted by a multitude of volunteers and extras who stepped in to recreate Haifa’s port during the Nakba. I’ve always wanted to ask him what it was like filming these scenes, with Tripolitan friends and comrades but also numerous Palestinians from Nahr el Bared (where he directed the eponymous film) and Beddawi camps, in 1982. They effectively re-enacted traumatic scenes – while waiting to return.

You refer to correspondence (between the PFLP and Baalbeck Studios) and invoke “voices of the absent ones” …

The Baalbeck Studios archive is a very chatty one! I felt the presence and had the sounds from the recording studio, the voices of so many divas, actors, singers, film professionals and the staff around me while working with the archive.

It took me five years, to find documents related to Palestinian and other revolutionary productions beyond the ones published in About Baalbeck Studios and Other Lebanese Sites of Memory.

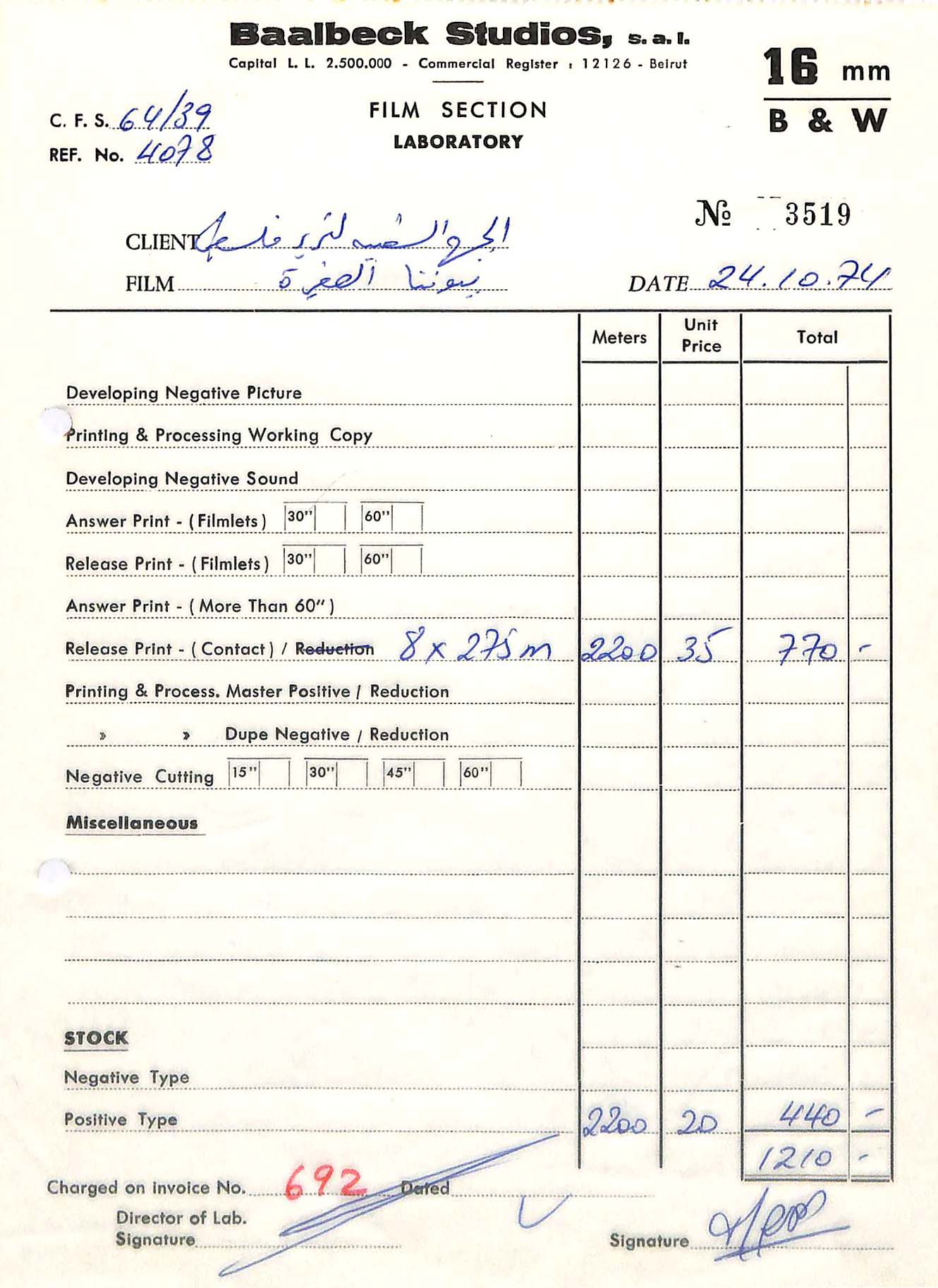

After sorting through and analysing the documents, I found first traces in the Baalbeck Studios lab, the editing room, and under categories such as Film Customers General A to Z or Sundry Clients. Indeed, these included the rental of a camera to film Ghassan Kanafani’s funeral procession – a service for which Baalbeck Studios did not charge the PFLP: I remember the budget line was crossed out with a red pen. One document from the Film Section Laboratory for a 16mm black & white film, again relates to the release print of footage shot at Ghassan Kanafani’s funeral.

What else was in there?

5. Interview with Khadijeh Habashneh, Nathalie Rosa Bucher, online, 31 October 2022.

Baalbeck Studios was a company, which did business with an array of clients within Lebanon and beyond. The one hundred thousand or so of documents I have scrutinised concerned primarily technical and financial matters. Only rarely did personal – or political – positions transpire. A handwritten letter sent from the Palestine Cinema Institute (PCI) in which a sender with an illegible signature refers to “Daoud Albina”, left me wondering about the paper trail and the (personal) relations between Baalbeck Studios staff and revolutionary filmmakers, editors or Palestinian cadres. Later on, Khadijeh Habashneh5 who witnessed the emergence of the PCI and was greatly involved in it, confirmed to me that Daoud (or David) Albina was their contact person at Baalbeck Studios.

I am indeed able to distinguish many staff handwritings, acronyms and signatures but have struggled with these letters sent from the PCI and PFLP. How nice of Bassam Abu Sharif, in his position as member of the PFLP politburo in charge of information, to have typed his name with a typewriter!

The acronym “AS”, for example, standing for Aïda Salloum, appeared in so many administrative documents from early 1966 onwards. I started to become truly obsessed with Aïda!

Director of photography Hassan Naamani simply said that when he went to Studio Baalbeck, he’d go straight to Aïda.

Aïda’s and financial controller Roger Anhoury’s acronyms, appear on the documents sent in 1976 by the PCI and PFLP to Baalbeck Studios. On one also appears “SK” for Stanley Khouri, the Palestinian sound engineer who built Baalbeck Studios’ superb sound studio.

And who was Aïda? She showed me some pictures of herself as a young woman dancing in Fairouz’ and Wadih and Marwan Jarrar’s troupe, when I first met her! She was a secretary, working from the office on the left, as one would get up the few steps leading into Baalbeck Studios. She was indispensable.

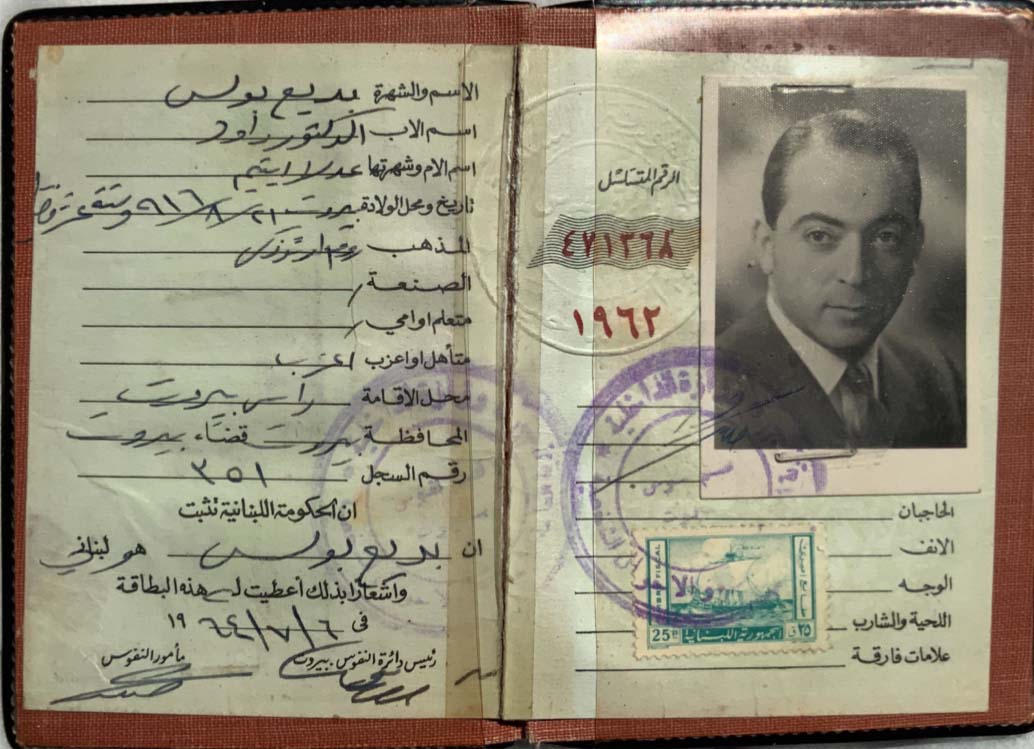

![Fig. 3 Badie Bulos’ I.D. issued in 1962, kindly made available by his niece Nevine Marchiset-Bulos. Unlike stated here, Bulos was born in 1915.]()

Badie Bulos was a naturalised Palestinian from Acre… From the documents I have read, he always struck me as exceedingly analytical and savvy – his company boasted state of the art equipment – but also generous and visionary. He intended on building a Hollywood-style studio in the hills above Beirut in Monteverde in 1966.

I am indeed able to distinguish many staff handwritings, acronyms and signatures but have struggled with these letters sent from the PCI and PFLP. How nice of Bassam Abu Sharif, in his position as member of the PFLP politburo in charge of information, to have typed his name with a typewriter!

The acronym “AS”, for example, standing for Aïda Salloum, appeared in so many administrative documents from early 1966 onwards. I started to become truly obsessed with Aïda!

Director of photography Hassan Naamani simply said that when he went to Studio Baalbeck, he’d go straight to Aïda.

Aïda’s and financial controller Roger Anhoury’s acronyms, appear on the documents sent in 1976 by the PCI and PFLP to Baalbeck Studios. On one also appears “SK” for Stanley Khouri, the Palestinian sound engineer who built Baalbeck Studios’ superb sound studio.

And who was Aïda? She showed me some pictures of herself as a young woman dancing in Fairouz’ and Wadih and Marwan Jarrar’s troupe, when I first met her! She was a secretary, working from the office on the left, as one would get up the few steps leading into Baalbeck Studios. She was indispensable.

Badie Bulos was a naturalised Palestinian from Acre… From the documents I have read, he always struck me as exceedingly analytical and savvy – his company boasted state of the art equipment – but also generous and visionary. He intended on building a Hollywood-style studio in the hills above Beirut in Monteverde in 1966.

6.

Meeting with Nevine Marchiset-Bulos, Nathalie Rosa Bucher, Beirut, 04 June 2019.

7. Habashneh, A. Khadijeh (2023), Knights of cinema the story of the Palestine Film Unit. Cham, Switzerland Palgrave Macmillan. p.127.

7. Habashneh, A. Khadijeh (2023), Knights of cinema the story of the Palestine Film Unit. Cham, Switzerland Palgrave Macmillan. p.127.

Whether he had any personal ties with any of the Palestinian revolutionary movements, I can’t tell. Nor did his late niece know.6

What is, however, crucial to note is that the Palestinian Film Unit (PFU) from its early days in Jordan in 1969, sent film material to Baalbeck Studios…7

Badie must have been supportive: without his approval, commercial feature films such as Reda Myassar’s Falistin al thaer (الفلسطيني الثائر), Kiffah hatta al tahrir (كفاح حتى التحرير) and Gary Garabedian’s Koullouna Fidayen (كلنا فدائيون), all released in 1969, and of course the dozens of revolutionary (mostly Palestinian) films and newsreels could never have made their way through the studios’ various departments!

I like to believe that he approved of the artistic and intellectual effort underway in the various Palestinian organisations, to make use of the medium of film, and to experiment with it, for revolutionary purposes. Whether he ever saw any of the films or corresponded with any of its filmmakers… I doubt it. Except maybe for Tewfik Saleh’s The Dupes as Saheb Haddad, the editor you mentioned above who worked for 12 years at Baalbeck Studios, co-edited this high-profile Syrian production.

I will tell you more about what films went through Baalbeck Studios in 1974 – a very busy year for the lab and other departments. Unlike other years, many of the documents describing the various work processes in 1974 survived…

What is, however, crucial to note is that the Palestinian Film Unit (PFU) from its early days in Jordan in 1969, sent film material to Baalbeck Studios…7

Badie must have been supportive: without his approval, commercial feature films such as Reda Myassar’s Falistin al thaer (الفلسطيني الثائر), Kiffah hatta al tahrir (كفاح حتى التحرير) and Gary Garabedian’s Koullouna Fidayen (كلنا فدائيون), all released in 1969, and of course the dozens of revolutionary (mostly Palestinian) films and newsreels could never have made their way through the studios’ various departments!

I like to believe that he approved of the artistic and intellectual effort underway in the various Palestinian organisations, to make use of the medium of film, and to experiment with it, for revolutionary purposes. Whether he ever saw any of the films or corresponded with any of its filmmakers… I doubt it. Except maybe for Tewfik Saleh’s The Dupes as Saheb Haddad, the editor you mentioned above who worked for 12 years at Baalbeck Studios, co-edited this high-profile Syrian production.

I will tell you more about what films went through Baalbeck Studios in 1974 – a very busy year for the lab and other departments. Unlike other years, many of the documents describing the various work processes in 1974 survived…

Beirut, 24 February 2024

Dear Nathalie,

I start writing this letter with a book in hand and with more thoughts concerning handwritings.

Beside me stands Palestinian Cinema, a precious publication by Kassem Hawal co-edited by Dar al-Awda and Dar al-Hadaf in 1979. The filmmaker dedicated this copy to one of his comrades, the Syrian film critic and communist Saïd Mourad. It's quite moving to know the name of the person who held a book before you and to ask yourself what it could mean to slide your eyes into theirs.

8.

Interview with with Kassem Hawal, Anaïs Farine, online, 05 April 2022.

To me, this book is significant because it includes several important documents and testimonies: the scenarios of Our Small Houses (بيوتنا الصغيرة, Kassem Hawal, 1974) and Land Day (يوم الأرض, Ghaleb Shaath, 1978), the telling of Hawal's encounter with pioneering Palestinian filmmaker Ibrahim Hassan Serhan (1915-1987) – who shot in Palestine before the Nakba – in Chatila in March 1974, as well as a survey that was distributed to the audience of the PFLP screenings in Beirut with the intent to study its tastes and the impressions left by the movies. Unfortunately, Kassem Hawal told me that no analysis was produced based on this survey.8

Here again we are left with missing answers...

![]()

![]() Fig. 4 Palestinian Cinema, Kassem Hawal, Dar al-Awda and Dar al-Hadaf, 1979.

Fig. 4 Palestinian Cinema, Kassem Hawal, Dar al-Awda and Dar al-Hadaf, 1979.

When imagining this exchange, we were hoping that following celluloid and paper trails would help appreciate how PFLP cinema did connect people. Your last letter is densely inhabited. I wonder if some of the Baalbeck Studios staff that you conjured had been attending the Arab Ciné-Club in Beirut that Kassem Hawal helped organise and where his film Our Small Houses was screened in 1974. The only members of the film society that matched with the archives of Baalbeck Studios are Hassan Naamani and director Sylvio Tabet.

I imagine film rolls being sent to Sin el-Fil in order to be printed and processed, then being routed to cultural and film clubs, schools and camps, where they could head their viewers toward political offices.

The films that have been looted, lost and destroyed are not merely artefacts; they are connectors crossing spaces and making people come together.

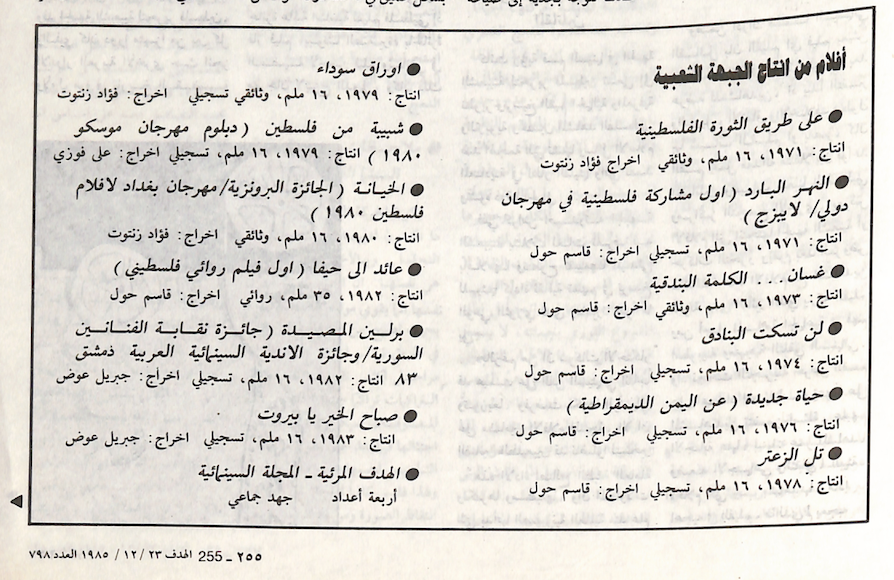

In December 1985, Al-Hadaf printed a list of films produced by the Popular Front since its inception. Kassem Hawal is credited for his work on no less than six titles. Our Small Houses, however, is not referenced in that list.

![Fig. 5 Al-Hadaf, n°798, 23/12/1985 (Courtesy of Abboudi Bou Jaoude)]()

Other filmmakers' names mentioned include the one of Fouad Zantout, a Lebanese editor whose work has been essential to the Cinema of the Palestinian Revolution at large. In 1977, he collaborated with Nabiha Lotfi on Because the Roots Will Not Die (لأن الجذور لن تموت) and with Adnan Madanat on Palestinian Visions (رؤى فلسطينية). As was the case for Hawal, Zantout also continued making PFLP produced films after the start of the war in 1975, but the demarcation line forced them to stop working with Baalbeck Studios and to find a fall-back solution in Italy.

Here again we are left with missing answers...

When imagining this exchange, we were hoping that following celluloid and paper trails would help appreciate how PFLP cinema did connect people. Your last letter is densely inhabited. I wonder if some of the Baalbeck Studios staff that you conjured had been attending the Arab Ciné-Club in Beirut that Kassem Hawal helped organise and where his film Our Small Houses was screened in 1974. The only members of the film society that matched with the archives of Baalbeck Studios are Hassan Naamani and director Sylvio Tabet.

I imagine film rolls being sent to Sin el-Fil in order to be printed and processed, then being routed to cultural and film clubs, schools and camps, where they could head their viewers toward political offices.

The films that have been looted, lost and destroyed are not merely artefacts; they are connectors crossing spaces and making people come together.

In December 1985, Al-Hadaf printed a list of films produced by the Popular Front since its inception. Kassem Hawal is credited for his work on no less than six titles. Our Small Houses, however, is not referenced in that list.

Other filmmakers' names mentioned include the one of Fouad Zantout, a Lebanese editor whose work has been essential to the Cinema of the Palestinian Revolution at large. In 1977, he collaborated with Nabiha Lotfi on Because the Roots Will Not Die (لأن الجذور لن تموت) and with Adnan Madanat on Palestinian Visions (رؤى فلسطينية). As was the case for Hawal, Zantout also continued making PFLP produced films after the start of the war in 1975, but the demarcation line forced them to stop working with Baalbeck Studios and to find a fall-back solution in Italy.

9.

Why did we plant roses: https://www.sunbirdfilms.se/work/roses I am grateful to Mohanad Salahat for sharing with me the inspiring treatment of his film project in 2021.

In Palestinian Identity (الهوية الفلسطينية, 1984), a film released after the 1982 Israeli invasion of Beirut, Kassem Hawal firmly testifies of the Zionist targeting of cultural and research centres. The archival library shots of the PFLP from which Hawal draws part of Our Small Houses was among the victims. While some of Hawal's photos and reels have been preserved and constitute the main topic of an ongoing film project by Ayed Nabaa and Mohanad Salahat9, I believe that the same does not apply to Zantout's archive. I am sure that his name appears in the documents that you researched. In the absence of the movies, is it possible to grasp the meaning of his contribution to the PFLP artistic and political line, hope and struggles from the Baalbeck Studios archives?

Beirut, 7 April 2024

Dear Anaïs,

Did you know that prior to working with the PCI, Fouad Zantout was assistant editor to two very popular movies Baalbeck Studios was involved in during the 60s? The Idol of the Crowds (فاتنة الجماهير, Muhammad Salman, 1965) and Mawal (موال, Muhammad Salman, 1966) both starring Sabah. Like other editors such as Nawal Costi, he was commissioned but not an employee.

A few Baalbeck Studios staff indeed assisted first the PFU and later worked at the PCI after 1976.

Dear Anaïs,

Did you know that prior to working with the PCI, Fouad Zantout was assistant editor to two very popular movies Baalbeck Studios was involved in during the 60s? The Idol of the Crowds (فاتنة الجماهير, Muhammad Salman, 1965) and Mawal (موال, Muhammad Salman, 1966) both starring Sabah. Like other editors such as Nawal Costi, he was commissioned but not an employee.

A few Baalbeck Studios staff indeed assisted first the PFU and later worked at the PCI after 1976.

10.

Interview with Kassem Hawal, Nathalie Rosa Bucher, online, 13 April 2023.

Previously, according to Kassem Hawal, “some Palestinian technicians work in [Baalbeck Studios]. They are professionals in showing and printing films, as well as in colour correction. I worked with them for free, and we started learning techniques that we did not know, including colour correction, where we used to correct colours with filters.” 10

A pioneer in colour correction in Lebanon was indeed David Albina, mentioned above, a naturalised Palestinian from Jerusalem, who worked in the lab of Baalbeck Studios for 13 years.

You referred to Zantout and probed whether the “meaning of his contribution to the PFLP artistic and political line, hope and struggles from the Baalbeck Studios archives” can be grasped.

A pioneer in colour correction in Lebanon was indeed David Albina, mentioned above, a naturalised Palestinian from Jerusalem, who worked in the lab of Baalbeck Studios for 13 years.

You referred to Zantout and probed whether the “meaning of his contribution to the PFLP artistic and political line, hope and struggles from the Baalbeck Studios archives” can be grasped.

11.

Habashneh, A. Khadijeh (2023), Op. cit.

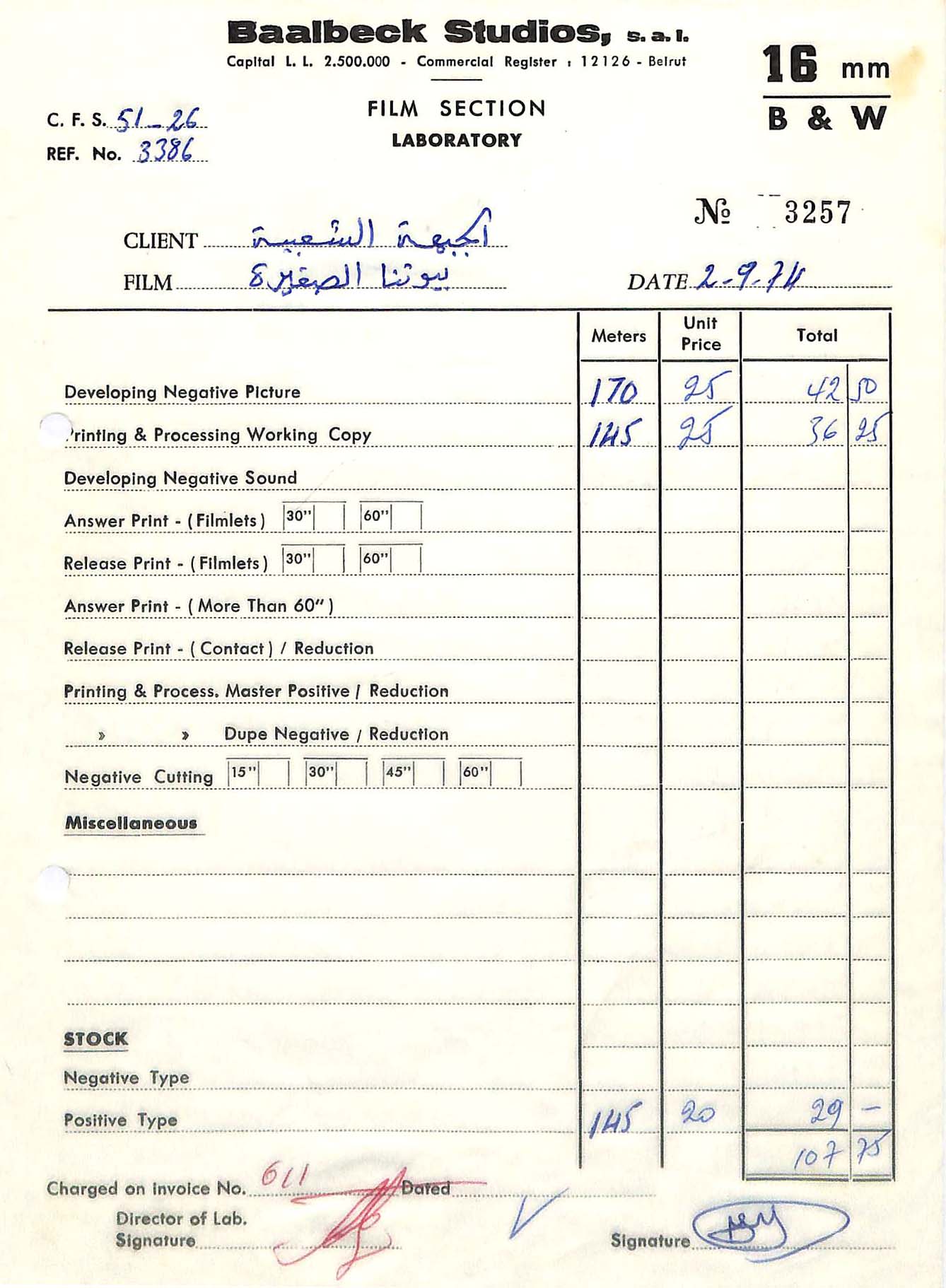

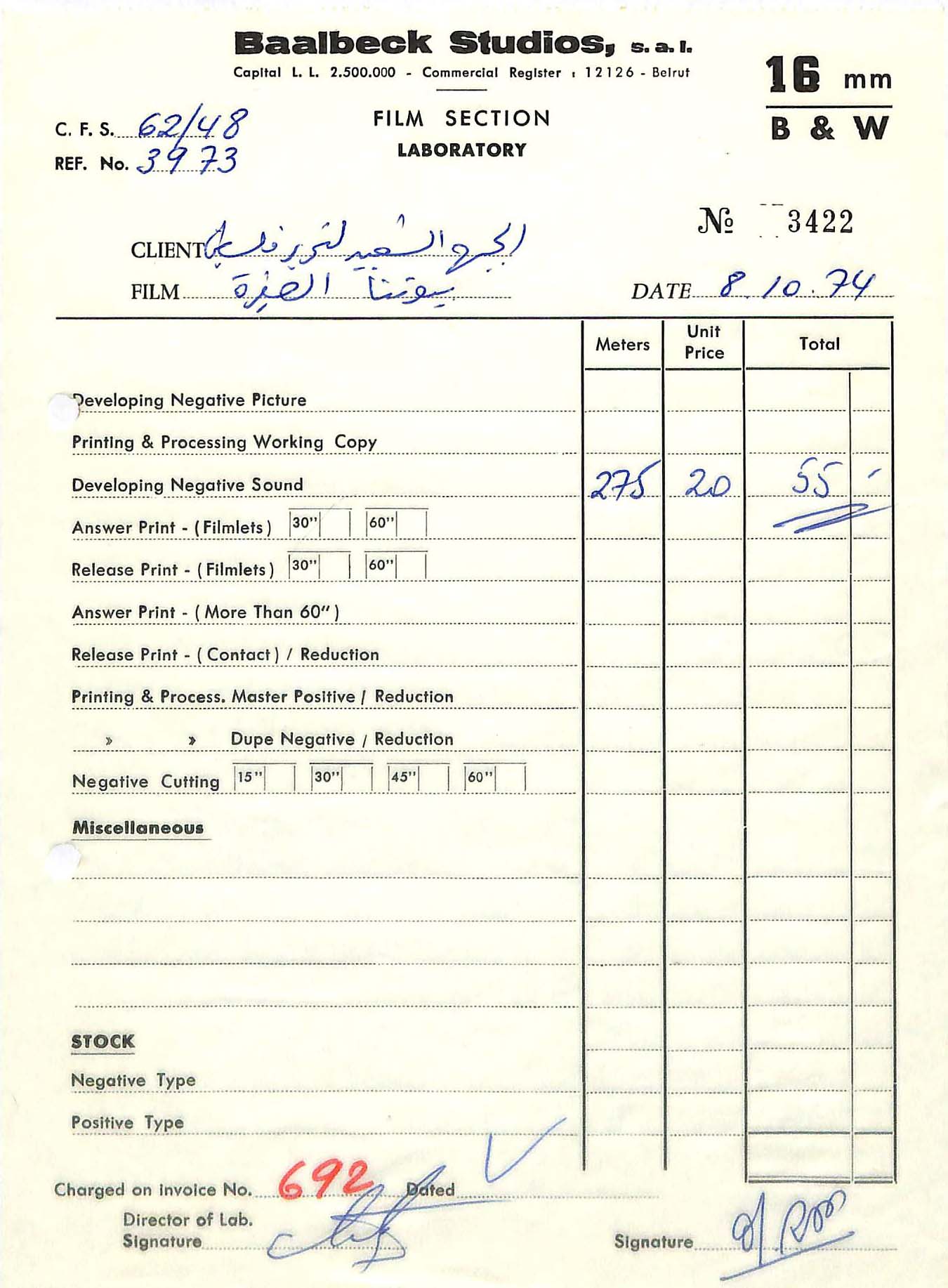

Khadijeh Habashneh credits him for joining the PCI since the early 70s where he worked on the United Media newsreels. These were under the supervision of Kamal Nasser until his assassination in 1973 and then the PCI. A paper trail of some of these newsreels11 are in UMAM’s Baalbeck Studios archives, together with one linked to Zantout’s documentary On the Path of the Palestinian Revolution (على طريق الثورة). Whereas the date on the documents in the Baalbeck Studios collection I recall is 1974, this does not necessarily reflect the date of production. As in the case of Hawal’s film Our small houses, these paper trails tell the production history:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fig. 6 Four of 15 documents issued for the film Our small houses to the PFLP dated between 2 September and 24 October 1974. Courtesy of UMAM D&R, Collection “Baalbeck Studios”.

We’re able to establish the approximate duration of the production (bearing in mind there may be lacunae) and chronology. Additional indications including specifications such as 16mm black & white film, the meterage, developing negative picture, printing and processing, negative cutting and release print or answer print, or dupe or zero copy, to name a few.

There is a field for notes (miscellaneous) where the director of the lab, Khalil “Toto” Khoury or David (in his incredibly neat handwriting) may leave a comment and sign off at the bottom. The second person to sign such documents would be the clerks of the lab who’d also file these forms. In 1974 this would be Mustafa Kassem or Mitri Yazbek with his ornate “MY” or the secretary “MRaï” (Mona Raï).

In closing, I would like to acknowledge Hawal’s pioneering role and the visionary approach he had in maintaining the nexus between revolutionary word and cinema:

Fig. 6 Four of 15 documents issued for the film Our small houses to the PFLP dated between 2 September and 24 October 1974. Courtesy of UMAM D&R, Collection “Baalbeck Studios”.

We’re able to establish the approximate duration of the production (bearing in mind there may be lacunae) and chronology. Additional indications including specifications such as 16mm black & white film, the meterage, developing negative picture, printing and processing, negative cutting and release print or answer print, or dupe or zero copy, to name a few.

There is a field for notes (miscellaneous) where the director of the lab, Khalil “Toto” Khoury or David (in his incredibly neat handwriting) may leave a comment and sign off at the bottom. The second person to sign such documents would be the clerks of the lab who’d also file these forms. In 1974 this would be Mustafa Kassem or Mitri Yazbek with his ornate “MY” or the secretary “MRaï” (Mona Raï).

In closing, I would like to acknowledge Hawal’s pioneering role and the visionary approach he had in maintaining the nexus between revolutionary word and cinema:

12. Interview with Kassem Hawal, Nathalie Rosa Bucher, online, 13 April 2023.

“Therefore, in addition to establishing the cinema department, I started heading the cultural section of Al-Hadaf magazine, so the written thought paved the way for the cinema industry.”12

13.

Ghassan Kanafani’s wife Anni, born Høver, hails from Denmark.

14. Interview with Nils Vest, Nathalie Rosa Bucher, online, 15 March 2024.

14. Interview with Nils Vest, Nathalie Rosa Bucher, online, 15 March 2024.

The Palestinian revolution drew many people to Beirut in the 70s. Danish filmmaker Nils Vest shot his documentary An Oppressed People is Always Right in Lebanon in late 1974. He made use of Baalbeck Studios at least once, and visited the PFLP offices. Being Danish he knew Anni Kanafani

13 – and he also recalls indeed meeting Kassem.14

He also took “historical archive material from the PLO's film office” back to Copenhagen…15

You lament the “missing answers” and I can only concur.

Most Baalbeck Studios feature films were issued a certificate of origin. The shards that we’re piecing together like investigators on a crime scene and the memories of surviving protagonists we gather are the birth certificates of these films.

You lament the “missing answers” and I can only concur.

Most Baalbeck Studios feature films were issued a certificate of origin. The shards that we’re piecing together like investigators on a crime scene and the memories of surviving protagonists we gather are the birth certificates of these films.

Nathalie Rosa Bucher

Nathalie Rosa Bucher is a writer and researcher with an academic background and has published features for South African, Lebanese, and international media. Extensive research on the old cinemas of Tripoli undertaken since 2013 has led to her joining UMAM’s Documentation and Research team, as an archives assistant and researcher and curating TripoliScope. She obtained an MPhil in Rhetoric Studies and Disaster Risk Science from the University of Cape Town and is particularly interested in arts and culture, heritage and memory, mobility, indigenous knowledge systems and livelihoods adaptations strategies.

︎︎︎ ︎

Anaïs Farine

Anaïs Farine is a cinema studies researcher and a film curator. She holds a Ph.D from the University of La Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris III. Her Ph.D thesis focused on the so-called “Euro-Mediterranean dialogue” and its Filmic Imaginary (1995 – 2017). Her writings have been published in Kohl, Cinematheque Beirut, Trouble dans les collections, Ettijahat, Débordements, The Funambulist Magazine, Africultures, and Aniki, among others. She is a member of the organizing committee of the Festival Ciné-Palestine (Paris).Profile text Anaïs Farine is a cinema studies researcher and a film curator. She holds a Ph.D from the University of La Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris III. Her Ph.D thesis focused on the so-called “Euro-Mediterranean dialogue” and its Filmic Imaginary (1995 – 2017). Her writings have been published in Kohl, Cinematheque Beirut, Trouble dans les collections, Ettijahat, Débordements, The Funambulist Magazine, Africultures, and Aniki, among others. She is a member of the organizing committee of the Festival Ciné-Palestine (Paris).