Kimia Talebi

Avani Ashtekar

Avani Ashtekar

Decolonising LSE

[1] The University and College Union (UCU) represents academics, post-graduates, and staff in universities across the UK. The UCU has been taking industrial action on pay and working condition disputes to resist the marketisation of higher education.

WORKS/ARCHIVES CITED

Lorde, Audre. 2019 [1984]. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” In Sister Outsider. Penguin Random House.

Olufemi, Lola. 2021. Experiments in Imagining Otherwise. Hajar Press.

Race Today Journals, MayDay Rooms.

The LSE Troubles, LSE Archives, LSE Library.

Lorde, Audre. 2019 [1984]. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” In Sister Outsider. Penguin Random House.

Olufemi, Lola. 2021. Experiments in Imagining Otherwise. Hajar Press.

Race Today Journals, MayDay Rooms.

The LSE Troubles, LSE Archives, LSE Library.

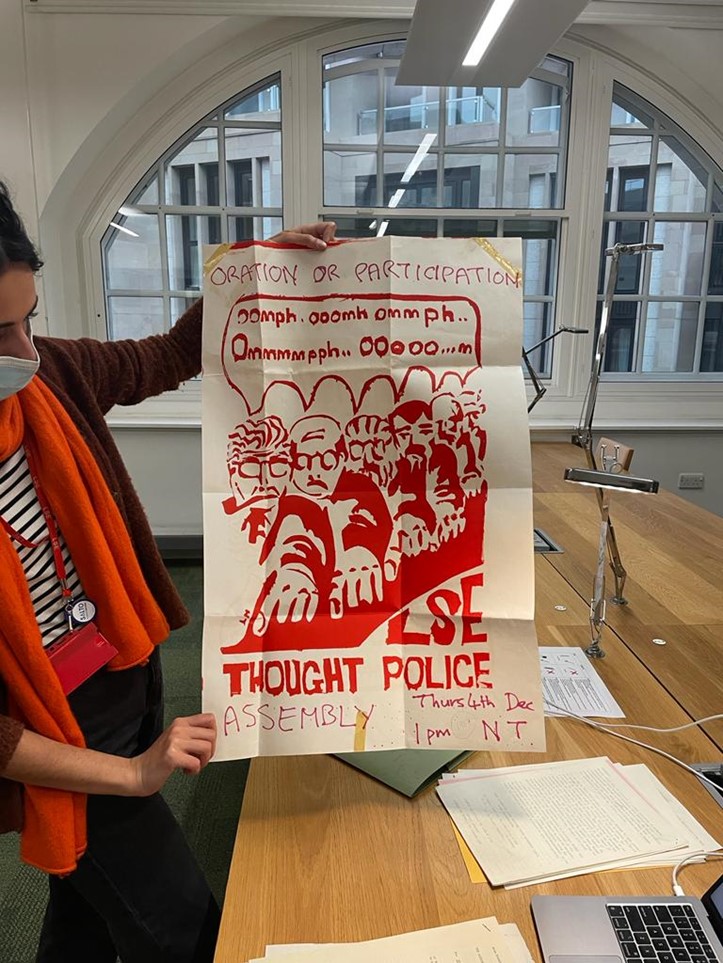

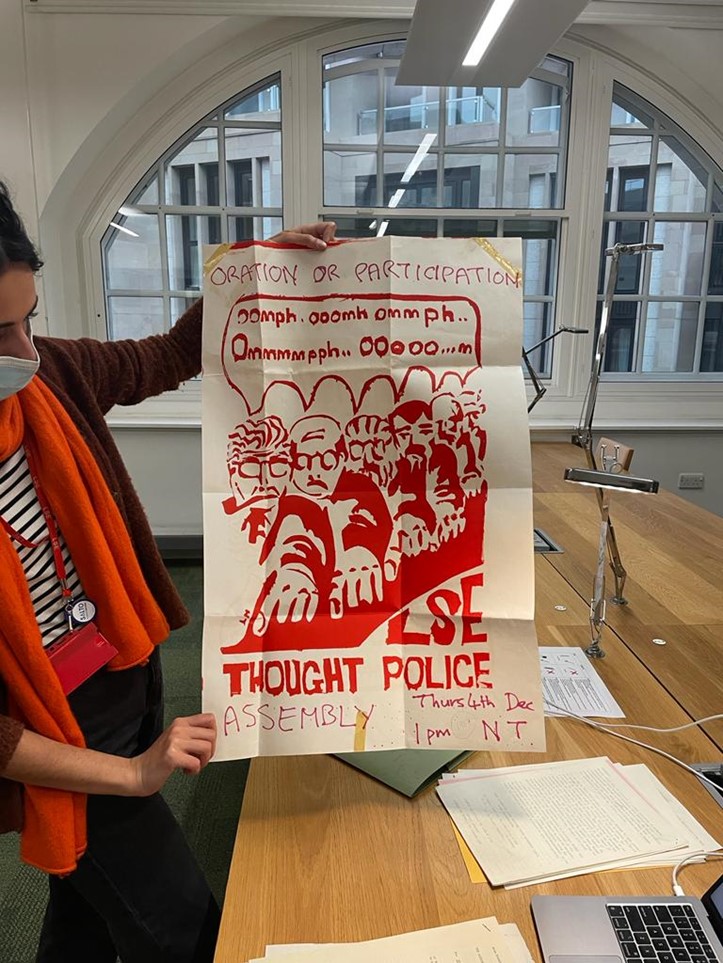

On 12th January 2022, the Radical

History working group met for the first time. The working group broached the

issue of tracing the collective’s work on a continuum of pre-existing radical

work happening on the campus. We were interested in showing the continuities of

movement-building and their undying relationship to past organising, like the

anti-apartheid movement of the late-1960s and student opposition to the appointment of Walter

Adams. Relatedly, we spoke of charting the histories of student and staff

dissent and the internationalism of the sixties and seventies in London. The

collective then planned to visit the archives in the LSE Library in sub-groups.

We were particularly interested in the “LSE Troubles” archive, which included

newspapers, posters, and articles from student groups.

Through this piece, we hope to find the space to discuss our experiences, reflections, and feelings from visiting the LSE archives. We (Avani and Kimia), write here as two student organisers involved in Decolonising LSE and its offshoot, the Radical History group. We place emphasis on the multi-sensorial nature of the archive: how we interact with archives through touch, smell, sound, and taste and reflect on how they make us feel. By understanding the archive as a living and breathing site of knowledge, conversations with past organisers can be made possible. Archives are spaces where radical movements not only leave their traces as repositories but are constantly in the making.

In Audre Lorde’s spin on a Descartes quote, Lorde declares “I feel, therefore I can be free” (Lorde, 2019: 27). We hope the discussions below on our feelings with the process of archiving presents the archive as an accessible space for all to engage with and archiving as a necessary praxis in movement-building. By feeling we can set the archive free.

Our written piece will hence take the style of a conversational-format. In our planning for this piece, we noted the difficulties of even imagining a collaborative approach to writing when all we have ever known of is marketised education, grading systems and essays that begin with “I”. We believe this conversational-format can best represent the conversations we have collectively had with the archive, and how we build connections between our lives, our organising, and the materials we engage with.

Through this piece, we hope to find the space to discuss our experiences, reflections, and feelings from visiting the LSE archives. We (Avani and Kimia), write here as two student organisers involved in Decolonising LSE and its offshoot, the Radical History group. We place emphasis on the multi-sensorial nature of the archive: how we interact with archives through touch, smell, sound, and taste and reflect on how they make us feel. By understanding the archive as a living and breathing site of knowledge, conversations with past organisers can be made possible. Archives are spaces where radical movements not only leave their traces as repositories but are constantly in the making.

In Audre Lorde’s spin on a Descartes quote, Lorde declares “I feel, therefore I can be free” (Lorde, 2019: 27). We hope the discussions below on our feelings with the process of archiving presents the archive as an accessible space for all to engage with and archiving as a necessary praxis in movement-building. By feeling we can set the archive free.

Our written piece will hence take the style of a conversational-format. In our planning for this piece, we noted the difficulties of even imagining a collaborative approach to writing when all we have ever known of is marketised education, grading systems and essays that begin with “I”. We believe this conversational-format can best represent the conversations we have collectively had with the archive, and how we build connections between our lives, our organising, and the materials we engage with.

Conversations

[2] On the 9th

November 2021, Tzipi Hotovely, the Israeli Ambassador to the United Kingdom who

denies the Nakba and self-identifies as a “religious right-winger,” was invited

to speak by the LSE SU Debating Society. LSE SU Palestine Society and the LSE

for Palestine coalition organised a protest and

walk out in response. The protest received widespread media

attention with politicians calling for further police presence and condemned

students in solidarity with Palestine.

Kimia Talebi: Hi Avani! Since our last

conversation, I visited the MayDay Rooms archive and was reflecting on our

earlier trip to the LSE archives. The gap between the two archives was

astounding. Whereas MayDay Rooms has community archives catered to current

movement-building, the LSE archives presents organising from the seventies as a

confined and fleeting moment in time. It felt like the spirit and high-energy

of the radical organisers we engaged with in the LSE archive were reduced to a

barcode in a catalogue. I wonder if you felt this too?

One thing I have found myself treasuring was the meeting the Radical History group had before visiting the LSE archives. The meeting occurred following a round of winter UCU strikes which renewed a joint motivation from students and staff that another university was possible. This staff-student unity fed into a zoom call filled with an excited nervousness in anticipation of what we may find in the archive, and the possibilities of public exhibitions, projects, teach-outs that this could inspire.

Though these meetings energised me, I cannot ignore attending the meeting flat on my feet and burnt out from the previous weeks. The protest against the Israeli ambassador occurred around two months before, giving rise to a pervasive police presence on campus.[2] I felt eager yet uneasy to learn about previous police presence on campus and how the university responded to radical student organising. Would a university archive even explicitly mention this? How would it make me feel in my state of burnout? Would it console me?

What feelings did the archive evoke in you?

One thing I have found myself treasuring was the meeting the Radical History group had before visiting the LSE archives. The meeting occurred following a round of winter UCU strikes which renewed a joint motivation from students and staff that another university was possible. This staff-student unity fed into a zoom call filled with an excited nervousness in anticipation of what we may find in the archive, and the possibilities of public exhibitions, projects, teach-outs that this could inspire.

Though these meetings energised me, I cannot ignore attending the meeting flat on my feet and burnt out from the previous weeks. The protest against the Israeli ambassador occurred around two months before, giving rise to a pervasive police presence on campus.[2] I felt eager yet uneasy to learn about previous police presence on campus and how the university responded to radical student organising. Would a university archive even explicitly mention this? How would it make me feel in my state of burnout? Would it console me?

What feelings did the archive evoke in you?

Avani Ashtekar: Hello, Kimia! As I am hearing you

speak, I am reminded of the student movements that took place against the

exclusionary Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in India in late 2019 and early

2020. Protesting students were not only penalised for their outward defiance

against violent exclusion by the state, but forcefully (yet partially)

silenced. I was not at home when the protests took place, but the firing rage

in the streets kept me warm and hopeful. So what is my archive of this student

movement? Clearly, I did not participate in them, but that does not mean that I

did not have any stakes in them. So, feelings of hope and rage are like an

archive for me. Fast-forward to December 2021. So many of us at the UCU pickets

were filled with similar feelings of rage and hope. How might the LSE archives

document this? I am not even sure that they will consider feelings to have an

archivability. So, like you said, the is a gaping hole between let’s say

hopeful archives that come from body and emotionality and archives as passive

repositories. We are taught that archives don’t alter what happens, they are

passive records of what has happened. I find that understanding pretty

weird.

I say this because I am thinking of the time when I was going to enter the LSE archives with comrades from the Radical History group. We were warned that the archive was going to close in about 40 minutes. At that moment, I found this temporal limit so strange. I was immediately hit with the feeling that I can only access the LSE archive in its preset limits - not only spatial but also temporal. So, the process of archiving i.e. keeping the archives in an institutionally monitored room already determined how we could engage with them.

Once we left the archive, I remember feeling like I had just been able to trace an incomplete genealogy of ongoing radical movements at the LSE. What were your thoughts and feelings after you left the archive? And did they change over time?

I say this because I am thinking of the time when I was going to enter the LSE archives with comrades from the Radical History group. We were warned that the archive was going to close in about 40 minutes. At that moment, I found this temporal limit so strange. I was immediately hit with the feeling that I can only access the LSE archive in its preset limits - not only spatial but also temporal. So, the process of archiving i.e. keeping the archives in an institutionally monitored room already determined how we could engage with them.

Once we left the archive, I remember feeling like I had just been able to trace an incomplete genealogy of ongoing radical movements at the LSE. What were your thoughts and feelings after you left the archive? And did they change over time?

KT: Yes, there were changes to how I felt once we engaged with the

archive. I remember feeling energised for future organising, as my group

searched through magazines which documented direct student action that

challenged LSE’s links to South African Apartheid. Both the direct action by

brave LSE students and the university reaction to radical organising reinforced

the cyclical nature of organising, as I thought of recent demonstrations and

strikes. This cycle reminds me of Lola Olufemi’s challenge to chronology in Experiments in Imagining Otherwise, and how the ‘temporal

regimes’ of past/present/future ‘encroach on one another’ (Olufemi, 2021: 32).

Future possibilities of organising can be forged by talking with, and through

the archive, to those that came before us.

Although I was excited for future organising, some of the uneasiness still remained. I remember a note, possibly from university administration, placed on top of a radical pamphlet that read “A pamphlet picked up in LSE by your faithful co-operation”. This note painfully brought me back to the realisation that the production of this archive could not have been possible without institutional surveillance of student and staff dissent. Consequently, the archive felt like a mode of surveillance, a collection of intel on the most visible of student organisers. The very name of the archive - “LSE Troubles” - scorns years of organising that confronted ongoing marketisation and securitisation of the university and presents these struggles as transient “phases” of the past.

How could I negotiate engaging with materials collected through institutional surveillance whilst the university still surveils student organisers who challenge links to Israeli Apartheid? How should we then navigate institutional archiving?

These are questions that I am still struggling with.

Although I was excited for future organising, some of the uneasiness still remained. I remember a note, possibly from university administration, placed on top of a radical pamphlet that read “A pamphlet picked up in LSE by your faithful co-operation”. This note painfully brought me back to the realisation that the production of this archive could not have been possible without institutional surveillance of student and staff dissent. Consequently, the archive felt like a mode of surveillance, a collection of intel on the most visible of student organisers. The very name of the archive - “LSE Troubles” - scorns years of organising that confronted ongoing marketisation and securitisation of the university and presents these struggles as transient “phases” of the past.

How could I negotiate engaging with materials collected through institutional surveillance whilst the university still surveils student organisers who challenge links to Israeli Apartheid? How should we then navigate institutional archiving?

These are questions that I am still struggling with.

[3] In 1966, Walter Adams, the principal of

University of Rhodesia, was appointed as new director of the LSE. Adams’

appointment triggered a long series of student protests, occupations, and

sit-ins against LSE administrators between 1966-1969 because of his colonial

investments in ‘Rhodesia’ (Zimbabwe). The dissenting students at LSE called

themselves the “new

radical left.”

![Student magazine from MayDay Rooms at the LSE UCU Picket Line]()

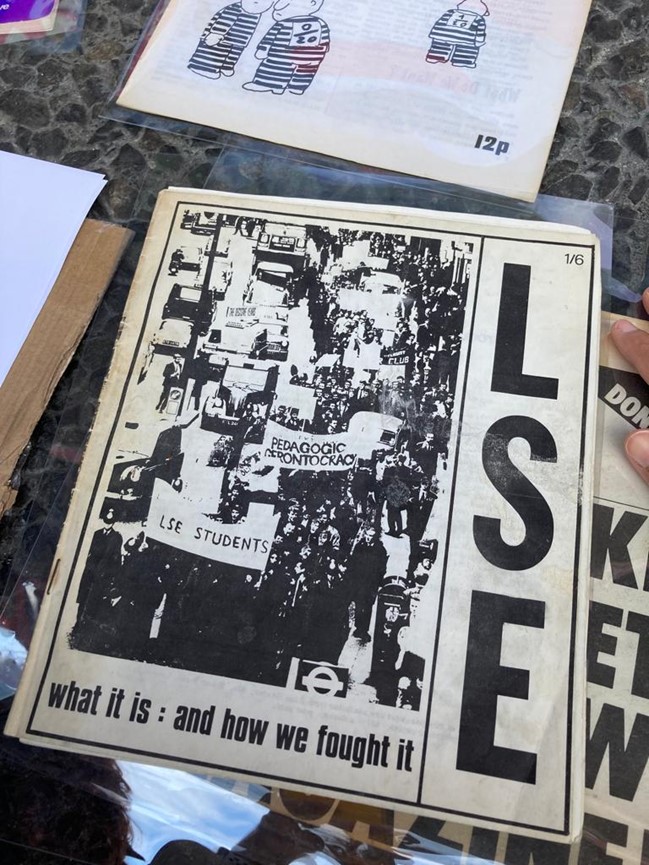

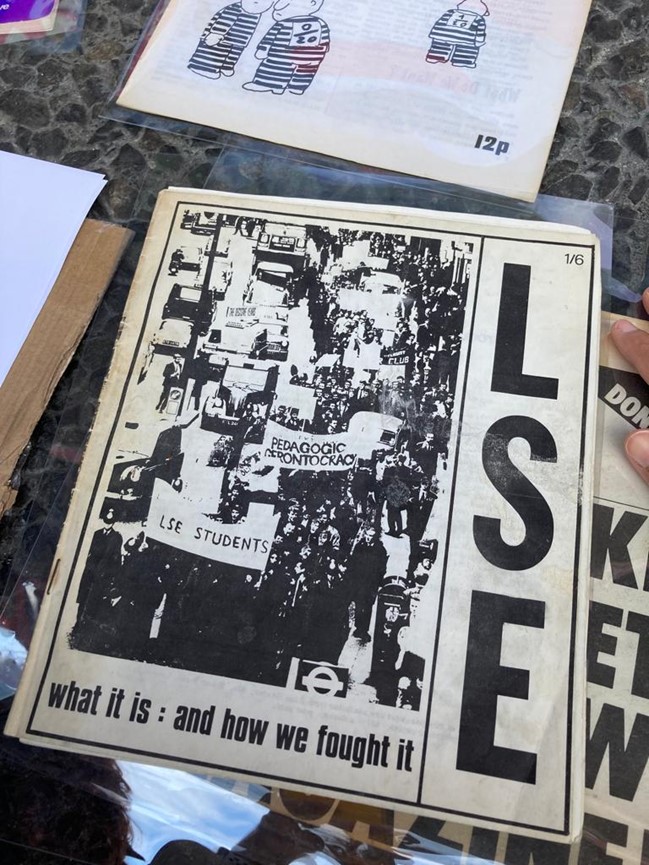

AA: I was definitely feeling this

discomfort too. If the LSE archives have labelled radical movements as “LSE

Troubles,” I was getting the sense that we could only find stories that the LSE

felt comfortable sharing. And yes, this name also treats agitations as seldom

occurring anomalies in a ‘smoothly functioning LSE.’ But in so doing, the

archive actually brings to fore how LSE is always troubled, if not haunted, by

ghosts of direct action and organising. But memories of an institution lie much

beyond its grasp and creep out.

When MayDay Rooms brought their archives to LSE’s picket lines, I was almost shocked to learn about all the student occupations that happened at LSE in the 60s.[3] When I was sifting through this material (absent in the LSE archives, to the best of my knowledge), I started feeling a mixed sense of excitement and sadness. These feelings don’t usually overlap well but reading lines like “...[t]his is why we live in a stifling and joyless ‘hall of learning’; why the ‘hallowed academic’ freedom rings hollow…” and “bombard the headquarters! All power to the people!” made me want to excitedly scream ‘people could fucking say that!?’ But the silence in the room was heavy. In a conventional archive, pin-drop silence is the norm. How might our experiences in archives differ if we can fearlessly exchange thoughts in the archive room? Doesn’t the silence in the room also speak to, if not equate with, a silence in the archives themselves? I am still pondering over these questions. Yet, it was obvious that the demands of the students were similar to those that we are making now and their anger against the liberal rhetoric echoes how we experience the LSE as students today.

Reading the pamphlets at the pickets also made me wonder how we were archiving the ongoing UCU strikes for future movements. So these archives of the ‘past’ made me think of the ways in which the present and futures will be remembered. I wanted to save the handouts and the printed copies of solidarity songs we sang, write down recipes of ‘cookies against casualisation,’ and the delicious baklava. In a strange way, I was getting nostalgic for the present and the futures to come. Can there be an archive of the future?

When MayDay Rooms brought their archives to LSE’s picket lines, I was almost shocked to learn about all the student occupations that happened at LSE in the 60s.[3] When I was sifting through this material (absent in the LSE archives, to the best of my knowledge), I started feeling a mixed sense of excitement and sadness. These feelings don’t usually overlap well but reading lines like “...[t]his is why we live in a stifling and joyless ‘hall of learning’; why the ‘hallowed academic’ freedom rings hollow…” and “bombard the headquarters! All power to the people!” made me want to excitedly scream ‘people could fucking say that!?’ But the silence in the room was heavy. In a conventional archive, pin-drop silence is the norm. How might our experiences in archives differ if we can fearlessly exchange thoughts in the archive room? Doesn’t the silence in the room also speak to, if not equate with, a silence in the archives themselves? I am still pondering over these questions. Yet, it was obvious that the demands of the students were similar to those that we are making now and their anger against the liberal rhetoric echoes how we experience the LSE as students today.

Reading the pamphlets at the pickets also made me wonder how we were archiving the ongoing UCU strikes for future movements. So these archives of the ‘past’ made me think of the ways in which the present and futures will be remembered. I wanted to save the handouts and the printed copies of solidarity songs we sang, write down recipes of ‘cookies against casualisation,’ and the delicious baklava. In a strange way, I was getting nostalgic for the present and the futures to come. Can there be an archive of the future?

KT: Yes, your point about the silence in

the room very much reflects silences in the archive.

Of the materials I engaged with, contributions on internationalism and direct action were mainly from white men writers. The presence of these writers starkly differed from the “Race Today” magazines I found at MayDay Rooms, with many entries written by Black organisers and minoritised students. I wondered - who is remembered in “LSE Troubles”?

I knew my questions regarding archival silences, specifically of Black and Asian organisers, could not be answered by institutional archives. For me, this is where imagination comes in. I imagined what the meetings looked like before a big action, such as the 1968 occupations of LSE buildings, and whether there was the same process of delegating roles, with a minute-taker hurriedly writing on paper. I imagined what the relationships between organisers were like, and whether they held anxieties about the ephemeral nature of student organising, just as we do.

I also wondered what the role of care was in organising, and whether organisers also struggled with burnout following an action. There were multiple times this past year where the adrenaline amongst students would dip following a round of UCU strikes or a demonstration, and many of us were left wondering how best to sustain energy when building longer campaigns. Although institutional archives may not present such clear-cut answers for present organisers, imagining the movements that these organisers inhabited in the sixties enables us to build on a long lineage of student and staff dissent.

It is through imagination where we can resist attempts from institutions to present organising and organisers as spectacles of the past. They live through us.

Of the materials I engaged with, contributions on internationalism and direct action were mainly from white men writers. The presence of these writers starkly differed from the “Race Today” magazines I found at MayDay Rooms, with many entries written by Black organisers and minoritised students. I wondered - who is remembered in “LSE Troubles”?

I knew my questions regarding archival silences, specifically of Black and Asian organisers, could not be answered by institutional archives. For me, this is where imagination comes in. I imagined what the meetings looked like before a big action, such as the 1968 occupations of LSE buildings, and whether there was the same process of delegating roles, with a minute-taker hurriedly writing on paper. I imagined what the relationships between organisers were like, and whether they held anxieties about the ephemeral nature of student organising, just as we do.

I also wondered what the role of care was in organising, and whether organisers also struggled with burnout following an action. There were multiple times this past year where the adrenaline amongst students would dip following a round of UCU strikes or a demonstration, and many of us were left wondering how best to sustain energy when building longer campaigns. Although institutional archives may not present such clear-cut answers for present organisers, imagining the movements that these organisers inhabited in the sixties enables us to build on a long lineage of student and staff dissent.

It is through imagination where we can resist attempts from institutions to present organising and organisers as spectacles of the past. They live through us.

AA: I am finding what you are saying so

valuable and also very validating. The role of care in organising is so hard to

unpack.

In parallel, I am also reflecting on care in the archive. Going back to my first visit to the LSE archives, because we were only left with a few minutes, I was trying to move through the files fast. But I realised that I could not, because I had to be really careful with how I touched the tattering newspaper clippings and other fragile ephemera that were preserved to essentially become eternal. So the notion of care and how the archive demands care became interesting for me. I remember thinking about what ways the archive is demanding care from us. Of course, there is care in tactility and in the storage of materials in conventional archives. But then it also has to do with why we care about them. Relatedly, how can we maintain archives in a way that we can expect people to care for the issues that they bring to surface? So caring became a much more layered notion for me and I have not been able answer these questions. And yet, these questions motivate me to think about archives and archiving differently.

In parallel, I am also reflecting on care in the archive. Going back to my first visit to the LSE archives, because we were only left with a few minutes, I was trying to move through the files fast. But I realised that I could not, because I had to be really careful with how I touched the tattering newspaper clippings and other fragile ephemera that were preserved to essentially become eternal. So the notion of care and how the archive demands care became interesting for me. I remember thinking about what ways the archive is demanding care from us. Of course, there is care in tactility and in the storage of materials in conventional archives. But then it also has to do with why we care about them. Relatedly, how can we maintain archives in a way that we can expect people to care for the issues that they bring to surface? So caring became a much more layered notion for me and I have not been able answer these questions. And yet, these questions motivate me to think about archives and archiving differently.

KT: I have not thought about what care

the archive demands from us - your questions are so crucial. Reflecting on our

conversations, how do you see archiving? What are some alternate processes of

archiving?

[4] Following are the first verses of a

protest anthem titled Hum Dekhenge (We shall see) that was widely sung during

the anti-CAA/NRC protests in India. It was originally written as a poem by Faiz

Ahmad Faiz and popularised in Iqbal Bano’s voice as a song against the Zia Ul

Haq regime in Pakistan: We shall see/

Certainly we, too, shall see/ that day that has been promised to us// when

these high mountains/ of tyranny and oppression/ turn to fluff and evaporate//

And we oppressed/ Beneath our feet will have/ this earth shiver, shake and

bear/ And heads of rulers will be struck/ With crackling lightening/ and

thunder roars.

![Picture of nail-painting at the LSE for Palestine and Decolonising LSE Day of Action]()

AA: To me, archiving entails not only a

process of remembering but also one of re-membering, which means, membering

what may have been forcibly dismembered or separated from one another. How do

we re-establish connections through archives? I have spoken about why I don’t

find conventional archives to be generative spaces on their own, but to add to

that list: the way in which conventional archiving uses specific categories

reifies borders. There is a constant need to master and control information.

This creates distance between things and events that are intimately connected.

Archives of connection might bring something to revolutionary work that siloed

archives cannot. In the “LSE Troubles” archives, there are pamphlets of

student movements in London in support of Black Panthers and Vietnam solidarity

marches. These archives show transnational connections but then what

alternative meanings of solidarity might spring up if we put the Black Panthers

archives in dialogue with those here in London?

Recently, my dad’s childhood friend was visiting us from Mauritius. He studied in my hometown with my dad and came back to India after 30 years. For the duration of his stay, he reunited with his friends from Fiji, from Ethiopia, and other parts of India. In a conversation with one of his friends, she reminded him of a Palestinian clubhouse from where they could regularly hear music. Then they went on to talk about the Nelson Mandela hostel in a neighbourhood two blocks away from home. All this was really surprising for me. My hometown is often only remembered as the headquarters of the militant arm (RSS) of the currently ruling fascist government of India. So if I want to know more about these radical histories, I might never be able to find a single archive that would allow me to stitch a narrative about these transnational connections. Then we must turn to stories and lores, music and jingles, and poetry.[4] So the archive is always in the making. We are re-membering. And you, how do you see archiving?

Recently, my dad’s childhood friend was visiting us from Mauritius. He studied in my hometown with my dad and came back to India after 30 years. For the duration of his stay, he reunited with his friends from Fiji, from Ethiopia, and other parts of India. In a conversation with one of his friends, she reminded him of a Palestinian clubhouse from where they could regularly hear music. Then they went on to talk about the Nelson Mandela hostel in a neighbourhood two blocks away from home. All this was really surprising for me. My hometown is often only remembered as the headquarters of the militant arm (RSS) of the currently ruling fascist government of India. So if I want to know more about these radical histories, I might never be able to find a single archive that would allow me to stitch a narrative about these transnational connections. Then we must turn to stories and lores, music and jingles, and poetry.[4] So the archive is always in the making. We are re-membering. And you, how do you see archiving?

KT: That’s so mad! - it is interesting how

radical histories still leave their traces in memory, even if physical remnants

of the Palestinian clubhouse are not present.

I see archiving in very similar ways to you. You mentioned earlier that the LSE archive felt like an “incomplete genealogy of ongoing radical movements at the LSE”. I agree and think it is up to us to fill these gaps. More importantly, we must also recognise that our movements are incomplete without the archive.

In the LSE Palestine Society x Decolonising LSE Day of Action during Israeli Apartheid Week, I publicly read an excerpt from a magazine in the “LSE Troubles” archive, where an LSE student questioned the term “student violence” used by the British state and press to undermine radical organising. As many students and staff are presently demeaned for confronting the marketisation of the university and institutional links to Apartheid, it was saying these words from an LSE student in the sixties that blurred the boundaries of past/present/future. I remember the warmth that rushed over my body, as it felt like I was standing indignantly with a comrade who had faced similar repression to us. When we actively integrate radical archives in our organising, we are provided with the solace that the movement has always been bigger than us.

I see archiving in very similar ways to you. You mentioned earlier that the LSE archive felt like an “incomplete genealogy of ongoing radical movements at the LSE”. I agree and think it is up to us to fill these gaps. More importantly, we must also recognise that our movements are incomplete without the archive.

In the LSE Palestine Society x Decolonising LSE Day of Action during Israeli Apartheid Week, I publicly read an excerpt from a magazine in the “LSE Troubles” archive, where an LSE student questioned the term “student violence” used by the British state and press to undermine radical organising. As many students and staff are presently demeaned for confronting the marketisation of the university and institutional links to Apartheid, it was saying these words from an LSE student in the sixties that blurred the boundaries of past/present/future. I remember the warmth that rushed over my body, as it felt like I was standing indignantly with a comrade who had faced similar repression to us. When we actively integrate radical archives in our organising, we are provided with the solace that the movement has always been bigger than us.

AA: Yes, and it will always be bigger than us…

KT: Regarding processes of archiving, it is important to reflect on what

our intentions are in visiting archives. In our group visit to the LSE

archives, it felt like we were speaking to student organisers in the archive as

fellow student and staff organisers interested in resurging past

eruptions of radicalism at the LSE.

I also see the act of archiving conversations, playlists from picket lines, the food we eat together during an action as central to sustaining organising. In my most recent organising space, our thoughtful discussions on care have left me reflecting on how community archiving is a form of collective care. Just as we treat the rich histories of organising present in MayDay Rooms and the LSE Archives with such tenderness, we should also take care in how we document group activities and learn from our interactions with one another e.g. who is most visible in our participatory archive, and how do we ensure everyone’s participation is equally represented?

On that note, what have you been listening to recently?

I also see the act of archiving conversations, playlists from picket lines, the food we eat together during an action as central to sustaining organising. In my most recent organising space, our thoughtful discussions on care have left me reflecting on how community archiving is a form of collective care. Just as we treat the rich histories of organising present in MayDay Rooms and the LSE Archives with such tenderness, we should also take care in how we document group activities and learn from our interactions with one another e.g. who is most visible in our participatory archive, and how do we ensure everyone’s participation is equally represented?

On that note, what have you been listening to recently?

AA: In between Doja Cat and Decol LSE x Palestine

playlist.

KT: That playlist is fire!

Avani Ashtekar recently completed her master's in Human Rights and Politics at LSE. Her research interests include histories of anticolonialism, internationalism, and postcolonial studies, and her work looks at instances of disobedience to anticolonial nationalism and migration. Currently, she is campaigning for gender and sexuality rights at an organization based out of Bengaluru, India.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎ ︎

Kimia Talebi is an organiser and historian based in London. She recently completed an MSc in International History at LSE.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎ ︎

Decolonising LSE is a collective of students, staff, and alumni working together to encourage the practice of decolonising across the London School of Economics. In this past year, we have organised several events online and in-person, demonstrations in solidarity with UCU strikes, and have co-organised with groups such as LSE for Palestine and LSE Justice for Cleaners. Decolonising LSE is made up of several working groups, including the Radical History group.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎ ︎