Asher Gamedze

Guerrilla archives:

Secret methods, ensembles of memory and the present

Guerilla study

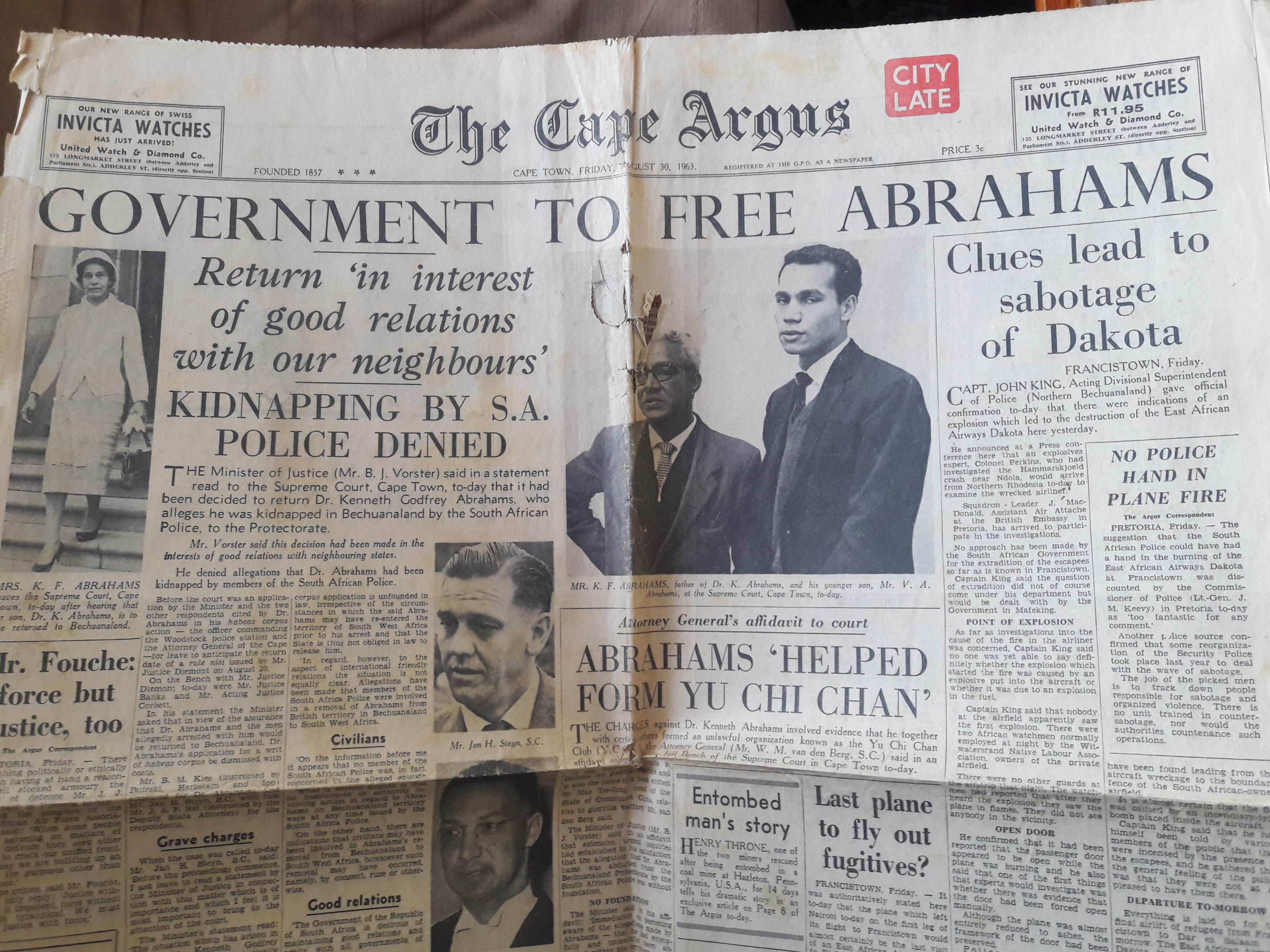

The Yu Chi Chan Club (YCCC) was a guerrilla study group established in 1961 in Cape Town, South Africa. I refer to it as a guerrilla study group for a few related reasons. Firstly, its content of study. They were learning about strategies and theories of guerrilla warfare by reading and discussing some of the world-historical processes in which it had been used as a method of revolutionary struggle. They were particularly fixated on the recent experiences in Cuba, China, Vietnam and the then-unfolding war in Algeria. Based on their studies and analysis, secondly, the YCCC planned to launch the National Liberation Front (NLF) - a network of cells of guerrillas across South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) that would carry forward the military phase of the revolution and overthrow the apartheid state. Third, the context of study: black life in apartheid society generally, and particularly in the wake of the Sharpeville Massacre (21 March 1960), was highly policed, tightly controlled and violently suppressed. The repressive state apparatus of the Afrikaner Nationalists was attempting to crush the liberation movement with renewed vigor and ferocity. Within this atmosphere, in enemy territory, this kind of underground organisation necessitated the orientation and tactics of the guerrilla merely to survive.

In one of their clandestine documents, distributed to their cells, the YCCC wrote:

It is quite obvious to all of us that we have to discuss the various methods of secret communications seriously. We realise that, as our groups grow and spread, we will find it necessary to transmit messages, reports, instructions, etc. from group to group. We have to be aware that if these messages are intercepted and read, the whole organisation will be endangered. Later, in the event of active hostilities, it will become even more urgent to send messages safely, speedily and secretly.1

While this quote refers specifically to communications, this orientation applied to all spheres of organising. The NLF policy on recruitment was as follows: prospective guerrillas who displayed discipline, commitment and ability through their work in political organisations should be identified. After being observed they should be independently and secretly vetted by two or three existing members. The NLF and its programme of armed struggle should then be proposed to them in theory, ie. without disclosing its actual existence. Thereafter, provided they passed the secret tests, could they be asked to join a cell in which only its leader would know any members of the organisation outside of that cell. Cloak-and-dagger stuff!

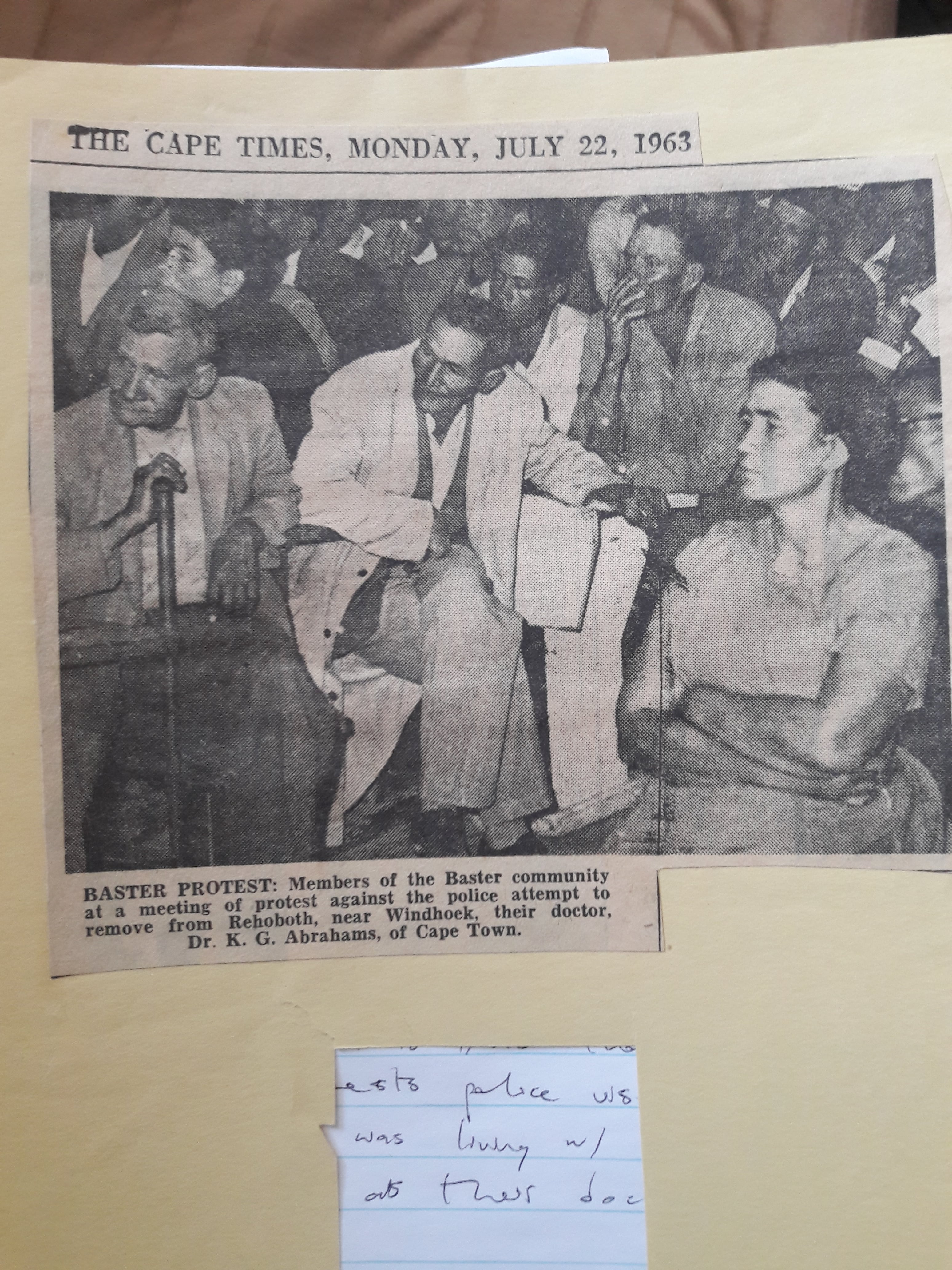

The tragic irony of the YCCC/NLF story was that, by some members’ own admission, it was their failure to follow their own strategies and policies of secrecy that - in addition of course to the context’s highly adverse repressive conditions – opened them up to infiltration. This infiltration by the Security Branch, in 1963, then led to the subsequent arrest, trial and the eventual incarceration of almost all of its key members for periods of five to ten years.

...

What I’m interested in exploring here in this piece happens at the intersection of a few things: the secretive strategies of guerrilla struggle, the impact of that mode of organising on people and their proclivity for trust - particularly in the wake of being infiltrated or sold out - and the implications thereof for the creation of archives and memories in the time-space of and between the moment of operation and the present. My process of doing research on the YCCC-NLF, and organisations that came before and after them, ie. their broader political tradition, encountered multiple different sites, containers, psyches and spaces of material and immaterial memory – all archives of different kinds, whose accessibility was contingent on a range of factors. Some of these factors were linked to the historical conditions of repression in the periods of struggle being studied. Some were linked to dynamics within the present. Many were shaped by the intervening years and the shifting balance of forces within them. And others were shaped by entirely subjective factors. These are collectively major factors in the production of silence and history.

Guerrilla sensibility

Through various organising processes between roughly 2015 and 2019, years before I decided to do a PhD, I met people who were previously members of, or were associated with the YCCC/NLF and people close to them. (In fact, this – meeting and talking to these people – is how my curiosity and fixation on the guerrillas first started to take serious shape.) Some of these people I collaborated with in popular education experiments, organising with youth and other activists. Others I met at workshops, protests, book launches or socially otherwise. Some I would consider my friends, and some I continue to work with today. Relationships, having their origin in organising work and/or some sense of a shared struggle, were not only the seed of the question in my life, but also held the latent possibility for its collective study.

After months of convincing him, I finally interviewed Comrade D. D was not a member of the YCCC/NLF but worked closely with its members in the 1970s and 1980s, joining and extending the ensemble. I have organised with and shared many social spaces with him over the last ten years or so. D was initially reluctant to be interviewed for the project but, because of the trust between us, the long experience working together, and many conversations about the project, he eventually agreed. In our conversation he declined to disclose certain details, mostly about others’ actions and involvement. Particularly if they themselves hadn’t gone on the public record to share that information. This reluctance that Comrade D had was shared by many who had been involved in underground struggle. Many people either declined to be interviewed for these and other reasons, or neglected to respond to my requests (perhaps for other reasons unknown to me). Some consented to a conversation but declined to a “proper interview” and requested to not be recorded or, some, even referenced in the project.

In the case of Comrades E and S, it was the intervention of their daughter, a friend and comrade of mine, that ultimately convinced them that I was trustworthy and urged them to respond to my at-that-time-unanswered requests, which they eventually did and I was able to have separate conversations with both of them. In another instance, it was somewhat by chance I was able to interview Comrade B. I bumped into him and his partner, Comrade M, at a small protest in solidarity with Palestine in early 2022. I had recently sent them both individual email requests for conversation-interviews to which they had not responded. At that time I didn’t really know them and they didn’t really know me. Seeing each other at a small protest of a handful of committed activists, provided a somewhat different way of connecting to a cold email. That was my ticket as it were. Perhaps Comrade B felt compelled, having seen me in person, to agree to the request, perhaps he felt less suspicious – I'm not sure. But he agreed to doing an interview after that encounter. I wasn’t so lucky with Comrade M.

Guerrillas archive

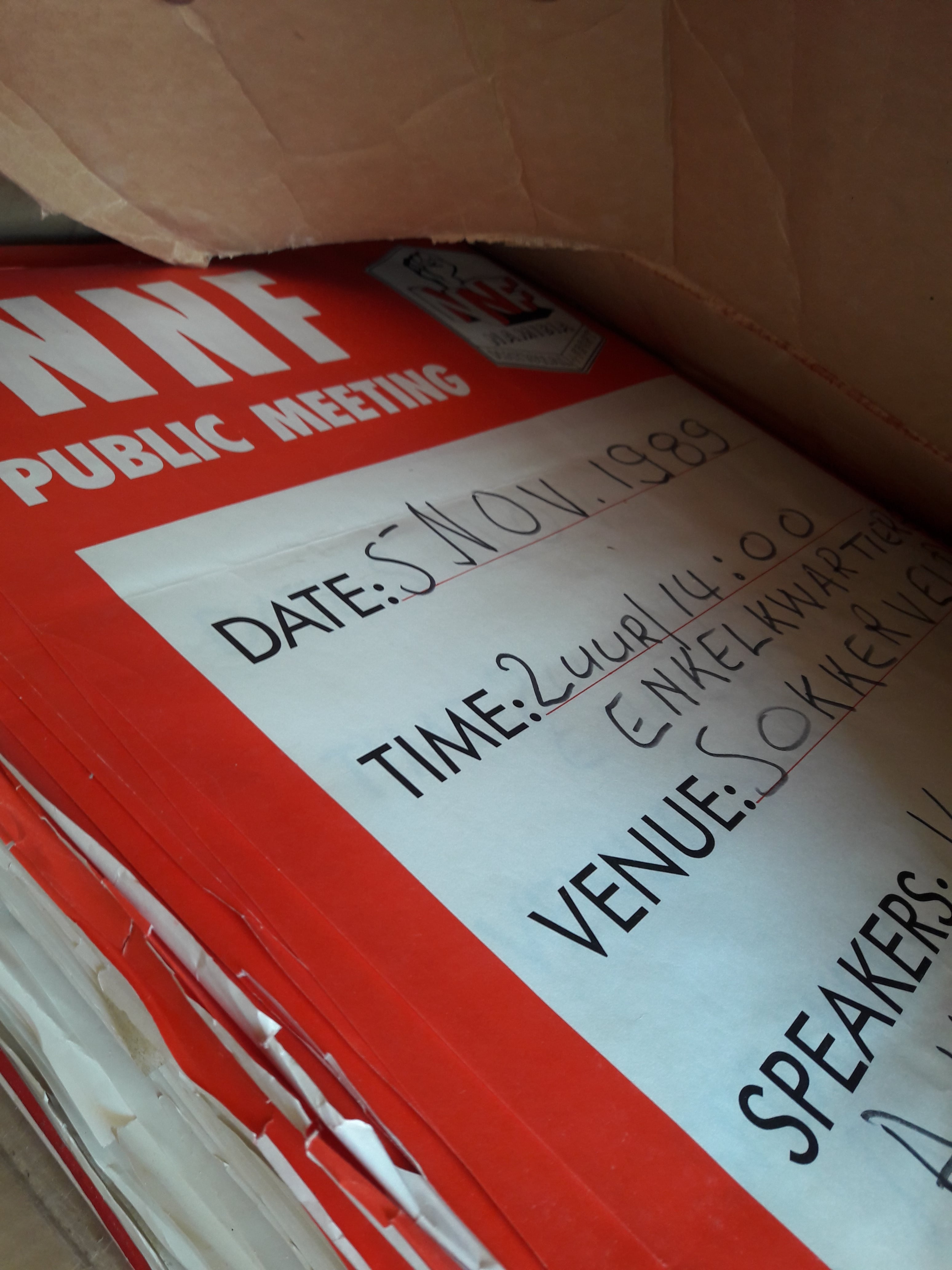

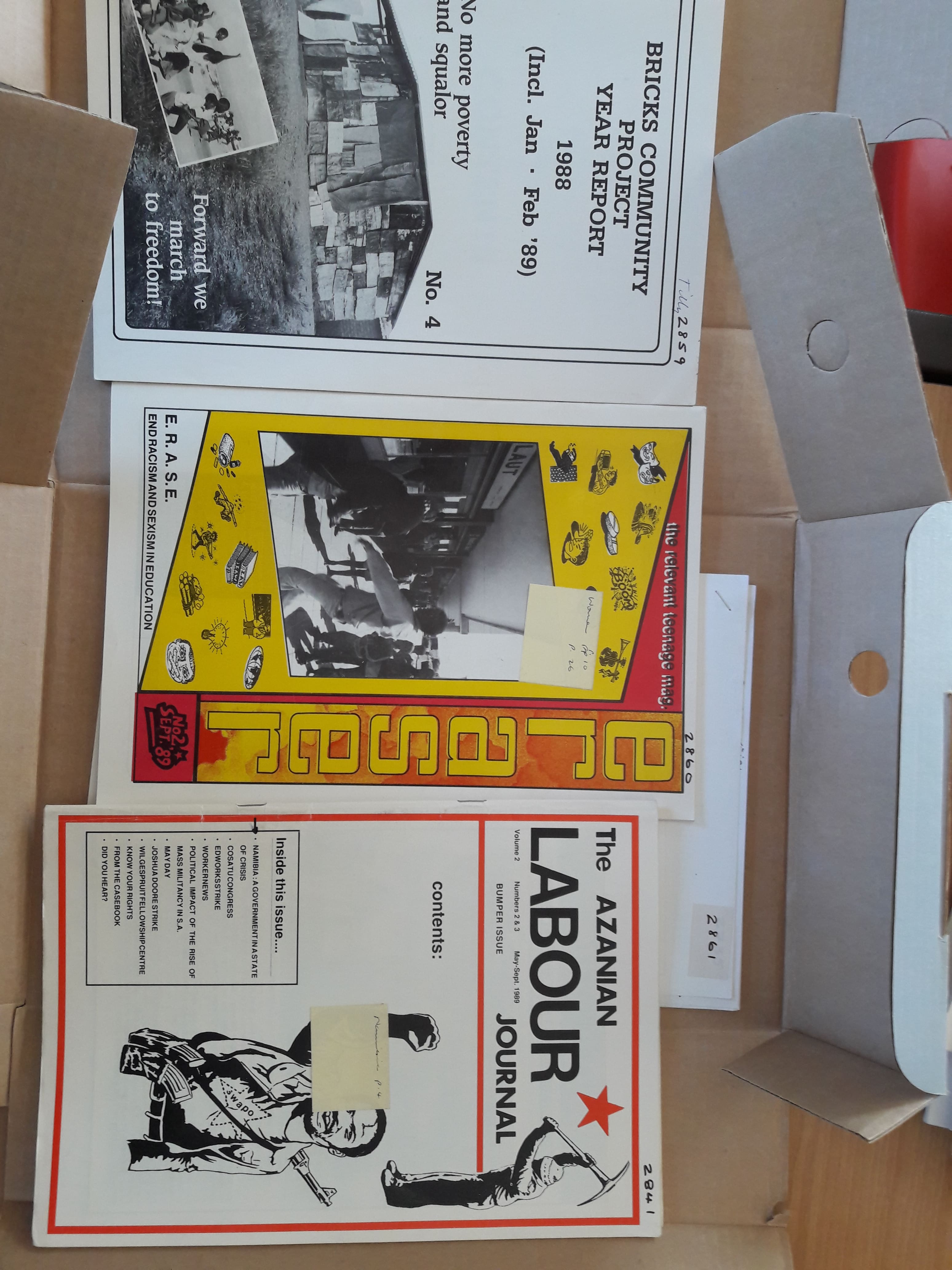

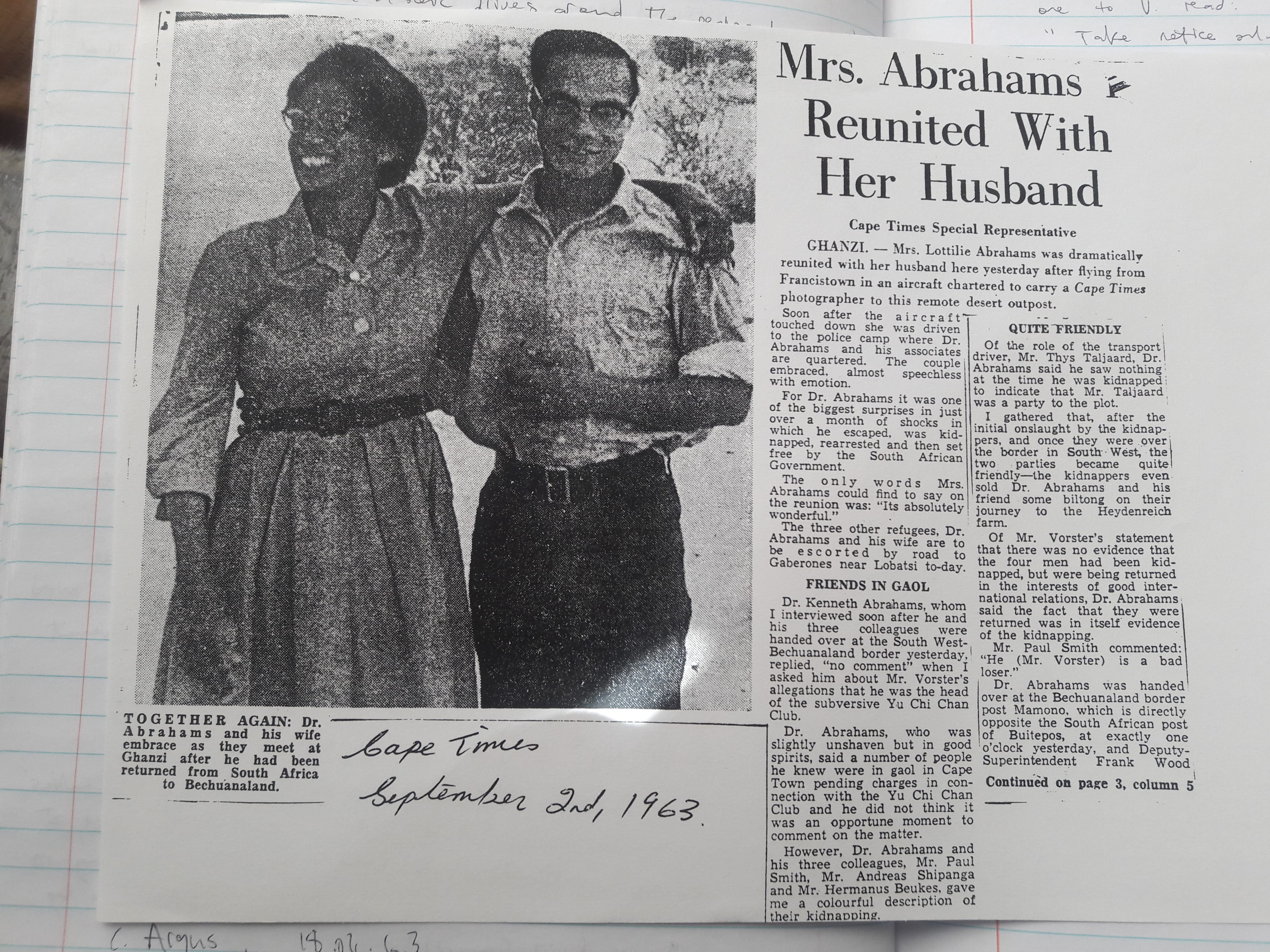

Ottilie and Kenneth Abrahams were two of the original YCCC/NLF ensemble. At the time of the arrest of the rest of the group in South Africa in mid-1963, the Abrahams were already organising in Rehoboth, South West Africa (SWA) as members of the South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO), their identity as NLF guerrillas being secret. They escaped arrest twice – in 1963 in SWA at the hands of the apartheid security forces, and in 1968 in Zambia after Kenneth Kaunda, under pressure from the apartheid regime, declared them “Prohibited Immigrants”. In the wake of these experiences of fleeing, afterwards, they kept everything – minutes from meetings, posters, publications they subscribed to, publications they produced, notes, etc. It was as if, in archiving everything, they were making up for lost time and the fact that their incarcerated comrades could not keep anything.

In Windhoek, today, the Abrahams family has thousands of Ottilie and Kenneth Abrahams’ (who are now late) documents from their almost five-decade involvement in Namibian liberation politics. Quite a treasure-trove for a radical history nerd interested in this marginalised history of independent socialist organising! These materials are spread out across a shipping container and a few offices at the independent school that the Abrahams founded in 1985. The sprawling collection spills over into various rooms in their family home, and exists in cupboards, shelves, filing cabinets, and in stacks on the floor. I spent many many many hours clearing out and (somewhat) organising the container which was storing old televisions, mattresses from youth camps, surplus and broken desks as well as decades of boxes filled with files, documents, papers, posters, patient records (Kenneth was also a general practitioner), receipts, books, journals, magazines, minutes from meetings, correspondence and letters to the editor of The Namibian Review (a journal they independently published), conference proceedings, etc.

While I was there in 2021, Windhoek was under Covid-19 lockdown regulations, one of which was a 9pm curfew. A few times I worked until the early hours of the morning at the Abrahams’ house and was invited to stay the night on a couch or mattress in the lounge instead of going to my accommodation to avoid breaking curfew. The family set me up with a little desk in the corner of the lounge on which I had piles of documents that I was looking through. Various members of the family were going about their business – in and out of the kitchen, passed out on the couches, watching the Olympics on television or chatting to me about what I was doing and their own memories of their grandparents. It’s clear to me that this intimate and familial experience of guerrilla study was only possible because of the work I had been involved in with members of the Abrahams family over the preceding 8-9 years.

Ensemble as guerrilla method

The collusion of harsh lockdown regulations around Covid-19 and a brutal 2021 fire that destroyed the Reading Room of the Special Collections Library at the University of Cape Town meant that I could not, during the whole process of my PhD, enter the archive which, prior to beginning, I thought would be central to my project. While this was a source of much frustration at some point, it opened me and the project up to a guerrilla sensibility, a whole other world of archives which necessitated relationships and was only made possible by other people’s generosity and trust. In order to do research in an official archive, with some exceptions, one generally only needs to complete some banal act registering yourself within the terms of order – fill in a form, or send a formal email request, sign in etc. One doesn’t need to have any kind of intimate or personal relationship with the materials they are using and one does not generally deal with the people who are connected to the documents. However, when documents exist in people’s houses, garages, bedrooms, lounges, drawers, studies, cupboards, etc., it is clear that an alternative set of logics and affective relations govern their accessibility. These collections are extensions of people, their lives and relationships.

With regards to material and memories archives of histories of guerrilla struggle, the secretive logics and security procedures of underground organising assimilated through years of operating under adverse conditions of repression, often determine and regulate access to them even in the present. Central to underground organising is ensemble, a mode of being and doing together as a trusted group of friends, comrades, and co-thinkers. Ensemble, which finds expression in guerrilla struggle in the form of the cell, is constituted by relationships that not only exceed and often predate but also make possible the political association. Given this, the method of studying these histories needs not only to be aware of the dynamics of ensemble, but also, join it. As Fred Moten suggests, one should not write about performance but with and for performance.2 Transposed to the present topic: one should, in the present, not merely write “about” guerrillas but join and extend the ensemble, study with and for them and the project. I think I’m still figuring out exactly what that means but I believe in it. What I know is that my experience of writing these histories relied on, or rather its very condition of possibility was relationships built through involvement in some kind of common project that stretches over time.

References:

- Yu Chi Chan Club. Pamphlet IV: Secret Communications. (Lead author: Elizabeth van der Heyden, independently produced and published by the Yu Chi Chan Club in Cape Town, 1962), P1.

- Rowell, Charles H., and Fred Moten. "" Words Don't Go There": An Interview with Fred Moten." Callaloo 27, no. 4 (2004): 954-966.

For more information on this history, see my PhD: Gamedze, Asher. "Ensemble study and struggle: A history of the Yu Chi Chan Club and the National Liberation Front." PhD diss., University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (South Africa), 2024.

Asher Gamedze

Asher Gamedze is a cultural worker based in Cape Town, South Africa, involved in music, education and history. As an independent musician he works as a drummer, composer and bandleader. A versatile drummer with an open sound and sensibility, Gamedze plays across and between multiple traditions of music including free improvisation, soul music, rock ‘n roll, and many locally situated traditions from Southern Africa. He has performed extensively in South Africa and other parts of the African continent including Egypt, Lesotho and Malawi. Gamedze has been on multiple European tours and has also played in the USA, particularly in Chicago where he has a big community.

Gamedze’s debut record as a bandleader, Dialectic Soul, was released to critical acclaim in 2020. The record received a rating of 8.0 from Pitchfork, was ranked in the New York Times’ Top Ten Jazz Albums of the Year and won ‘Best Traditional Jazz Album’ at the Mzantsi Jazz Awards. His second release, Out Side Work, consisting of two improvised duets with saxophone players Alan Bishop and Xristian Espinoza, came out in April 2022. He toured that record with reedman Xristian Espinoza in Europe in September 2022 and, in November 2022, toured Dialectic Soul, playing venues and festivals such as Jazzfest Berlin, Le Guess Who? and Flagey.

Gamedze’s International Anthem debut, Turbulence and Pulse, was released in early 2023 and featured his quartet of Robin Fassie (trumpet), Buddy Wells (tenor saxophone), and Thembinkosi Mavimbela (double bass), as well as vocalist Julian ‘Deacon’ Otis. It received 4.5 stars and a rave review from All Music: “at once remarkably adventurous and profoundly accessible.

︎ ︎ ︎

Asher Gamedze is a cultural worker based in Cape Town, South Africa, involved in music, education and history. As an independent musician he works as a drummer, composer and bandleader. A versatile drummer with an open sound and sensibility, Gamedze plays across and between multiple traditions of music including free improvisation, soul music, rock ‘n roll, and many locally situated traditions from Southern Africa. He has performed extensively in South Africa and other parts of the African continent including Egypt, Lesotho and Malawi. Gamedze has been on multiple European tours and has also played in the USA, particularly in Chicago where he has a big community.

Gamedze’s debut record as a bandleader, Dialectic Soul, was released to critical acclaim in 2020. The record received a rating of 8.0 from Pitchfork, was ranked in the New York Times’ Top Ten Jazz Albums of the Year and won ‘Best Traditional Jazz Album’ at the Mzantsi Jazz Awards. His second release, Out Side Work, consisting of two improvised duets with saxophone players Alan Bishop and Xristian Espinoza, came out in April 2022. He toured that record with reedman Xristian Espinoza in Europe in September 2022 and, in November 2022, toured Dialectic Soul, playing venues and festivals such as Jazzfest Berlin, Le Guess Who? and Flagey.

Gamedze’s International Anthem debut, Turbulence and Pulse, was released in early 2023 and featured his quartet of Robin Fassie (trumpet), Buddy Wells (tenor saxophone), and Thembinkosi Mavimbela (double bass), as well as vocalist Julian ‘Deacon’ Otis. It received 4.5 stars and a rave review from All Music: “at once remarkably adventurous and profoundly accessible.

︎ ︎ ︎