Sheng Zhang

In Search of the Process of Anti-Colonial Solidarity-Building: How I Used Archives to Explore the History of China-Palestine Solidarity Networks

In the year of 2021, when I was collecting primary sources for my Masters’ degree thesis for the Middle Eastern Studies program at Harvard University, I visited the Second Historical Archives of China in Nanjing where the majority of historical archives of the Republic of China (1911-1949) are stored. My Master’s thesis was on the topic of the Jadid Movement in Xinjiang region and its connections with pan-Turkist political movements in that region from the 1930s to 1940s. In the Second Historical Archives of China, I collected a number of useful references, including an important report written by a Han Chinese official in Xinjiang to Chiang Kai-shek, then supreme leader of the Republican government. This report unveils the Chinese government’s ways of thinking toward ethnic conflicts in Xinjiang region in the 1930s, and thus it is a truly important reference for my own research. The report was written in classical Chinese in a beautiful and nearly poetic language which deeply amazes me. Therefore, after taking down notes about its arguments, I requested a librarian in the Second Historical Archives to print it out so that I can have a copy to enjoy the beauty of the poetic language. The librarian had a quick glance of the document, and he saw a number of deemed “sensitive” words in it: Uyghurs, Kazakhs, ethnic policy etc. He then not only refused to print it, but also even deleted the scanned version of the entire report from the online database, making me the last person who had the privilege to access this report from the online database.

This behavior of intentionally hiding historical archives seems to be a quite common practice in the Second Historical Archives of China. Most researchers like me are not granted the opportunity to directly access the original paper copies of the archives, and thus we have to rely on the Archives’ online database. The problem, however, is that the librarians, for political reasons, would never upload archives related to so-called “sensitive” issues into the database anyway. For example, I was not able to find anything in the database related to internal discussions within the Chinese government about ethnic conflicts in the 1920s-1930s. The only report I discovered is the aforementioned one, and the reason why it spared the censorship in the beginning is because the report is attached to a previous document on the agricultural data of Xinjiang in the 1930s which hides it from the censorship of the librarians.

A more concerning reality for researchers is that, the Second Historical Archives of China stores the archives of the Republic of China era (1911-1949), the regime that existed before the current People’s Republic of China (PRC). Access to even archives of a non-existing historical regime one hundred years ago can be so inconvenient, and thus one can imagine how difficult it is to access archives related to the core state policies of the PRC.

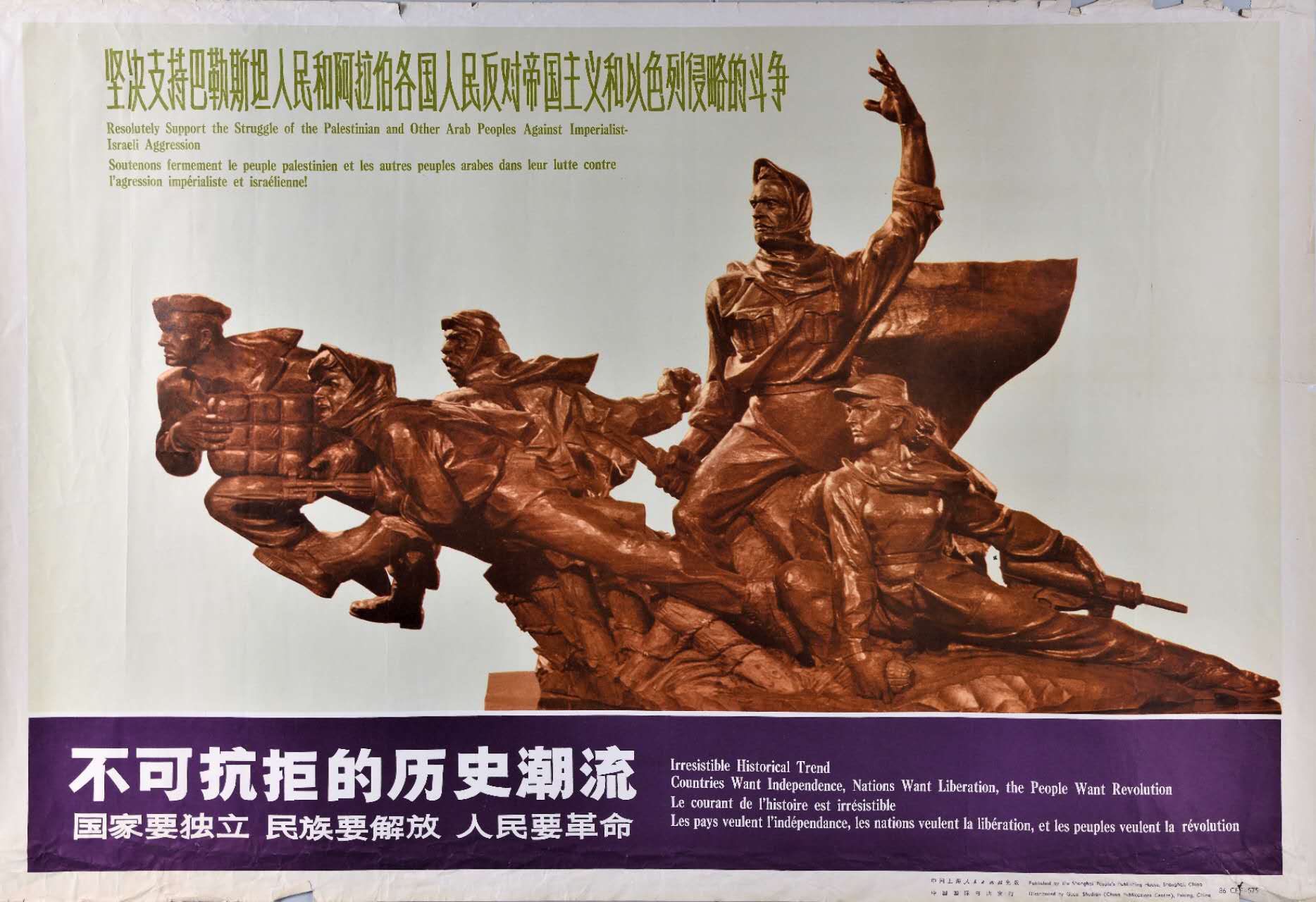

My current research is focusing on the foreign policy aspects of the PRC, specifically on how the PRC, in the Maoist era (1949-1976), built solidarity networks with national liberation movements in the Third World and supported global anti-imperialist and leftist insurgencies. In 2021, I published an article on The International History Review in which I analyzed the evolution of the PRC’s perception of the Arab-Israeli conflict in 1950s-1970s and how the Chinese and Japanese far-Left eventually imagined the national liberation movement of Palestine as the frontier of global revolution in the 1960s-1970s. More recently, in 2025, I finished an article on the evolution and vicissitude of the PRC’s foreign policy toward Palestine and on the history of China-Palestine solidarity movement from the 1950s to 2024. This article is titled “From Global Anti-Imperialism to the Dandelion Fighters: China’s Solidarity with Palestine from 1950 to 2024,” and it was published by the Transnational Institute.

This research interest of mine is a topic related to foreign policy of the PRC, which is of course seen as a “sensitive” topic. Access to archives stored in the Foreign Ministry of China would be a very difficult and costly task. Therefore, instead of going through the pain of dealing with the state-operated official archives institutions, I have been mostly depending on public sources of information published in the 1950s-1970s.

This behavior of intentionally hiding historical archives seems to be a quite common practice in the Second Historical Archives of China. Most researchers like me are not granted the opportunity to directly access the original paper copies of the archives, and thus we have to rely on the Archives’ online database. The problem, however, is that the librarians, for political reasons, would never upload archives related to so-called “sensitive” issues into the database anyway. For example, I was not able to find anything in the database related to internal discussions within the Chinese government about ethnic conflicts in the 1920s-1930s. The only report I discovered is the aforementioned one, and the reason why it spared the censorship in the beginning is because the report is attached to a previous document on the agricultural data of Xinjiang in the 1930s which hides it from the censorship of the librarians.

A more concerning reality for researchers is that, the Second Historical Archives of China stores the archives of the Republic of China era (1911-1949), the regime that existed before the current People’s Republic of China (PRC). Access to even archives of a non-existing historical regime one hundred years ago can be so inconvenient, and thus one can imagine how difficult it is to access archives related to the core state policies of the PRC.

My current research is focusing on the foreign policy aspects of the PRC, specifically on how the PRC, in the Maoist era (1949-1976), built solidarity networks with national liberation movements in the Third World and supported global anti-imperialist and leftist insurgencies. In 2021, I published an article on The International History Review in which I analyzed the evolution of the PRC’s perception of the Arab-Israeli conflict in 1950s-1970s and how the Chinese and Japanese far-Left eventually imagined the national liberation movement of Palestine as the frontier of global revolution in the 1960s-1970s. More recently, in 2025, I finished an article on the evolution and vicissitude of the PRC’s foreign policy toward Palestine and on the history of China-Palestine solidarity movement from the 1950s to 2024. This article is titled “From Global Anti-Imperialism to the Dandelion Fighters: China’s Solidarity with Palestine from 1950 to 2024,” and it was published by the Transnational Institute.

This research interest of mine is a topic related to foreign policy of the PRC, which is of course seen as a “sensitive” topic. Access to archives stored in the Foreign Ministry of China would be a very difficult and costly task. Therefore, instead of going through the pain of dealing with the state-operated official archives institutions, I have been mostly depending on public sources of information published in the 1950s-1970s.

First, state-run newspapers in the 1950s-1970s are very helpful archives for my research. One particular source I utilize for my research is the People’s Daily, which is the PRC’s official mouthpiece. This newspaper is affiliated to the Chinese government, and the changing propaganda tone of the Peoples’ Daily can reflect the changing of the Chinese official policy. For example, in the early 1950s, the Peoples’ Daily’s comment on the Palestine-Israel conflict focused only on criticizing Western imperialism, but did not openly criticize Israel itself. During the Suez Crisis of 1956, however, the Peoples’ Daily for the first time defined Israel as “a voluntary little pawn on the chessboard of Western colonizers.” In the 1960s-1970s, when the PRC entered its most ideologically radical phase in which it supported global insurgencies against imperialism, the People’s Daily adopted a more derogatory term to refer to Israel: “running dogs of U.S. imperialism.” The increasingly harsh and derogatory images of Israel on the People’s Daily reflect the trend of the PRC’s foreign policy toward the Middle East in this era.

In addition, the Peoples’ Daily also is a good source helping me to know more about what international events the Chinese government cared about the most in this era, how the Chinese government perceived the world in this era, and what the Chinese government did or claimed that it did to strengthen China-Palestine and China-Arab solidarity in this era. Besides the People’s Daily which is the mouthpiece of the Chinese central state, each province in China also had their official newspaper, which can be very helpful for my research as well. For example, the May 16th, 1969, the date marking the beginning of the Cultural Revolution of China, the Inner Mongolia Daily dedicated an entire page to Palestine, covering China’s military aid to the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and Syria, the PLO’s recent success in guerilla warfare, and commenting on the most recent diplomatic moves of the U.S.S.R and the U.S. regarding the Palestinian national liberation movement.

The largest advantage of official newspapers as a source is that it is very easy for researchers to access, as one can easily find these newspapers either on market or freely on state-run community libraries in China.

Besides state-run newspapers, another type of primary source I prefer to use is historical material officially published by the Chinese state. The PRC and the ruling Communist Party of China (CPC) have a number of affiliated departments and research centers specializing in editing, publishing, and sometimes analyzing archives of the Chinese state and the CPC. Materials published by these departments contain various types of useful historical references, including but not limited to official government documents, heads of states’ public and private speeches, records of important diplomatic events, and letters exchanged between government officials. In the case of my aforementioned research on China-Palestine relations, for example, I collected a number of very useful materials published by the Party Literature Research Center of the CPC Central Committee. This office affiliated to CPC Central Committee edited and published a multi-volume Chronicle of Zhou Enlai: 1949-1976 and Chronicle of Mao Zedong:1949-1976, and these multi-volume chronicles provided a very detailed record on what Mao and Zhou wrote about Palestine in public government documents, what they mentioned about Palestine in public diplomatic speeches, and what they said about Palestine in confidential meetings with foreign high-ranked officials from Palestine, the Arab World, and other Third World countries.

The largest advantage of this type of materials is that it is a great substitution of archives: First, these materials are all published books that one can easily access in either libraries or the markets, and thus one does not need to go through the pain of dealing with the bureaucracy of state-operated archives. Second, these materials are official historical accounts of the Chinese state or the CPC, and thus the credibility of these materials should be regarded as the same as archives stored in the Archives Office of the Foreign Ministry or other state-operated archives.

Of course, just like archives accessed in state-run archives, these materials are also official narratives of history that have gone through selections and censorship, and thus researchers must approach them with critical thinking. I, however, discovered a good way to re-verify these materials: Since these archival departments are part of the Chinese government, their selection and publication of materials are also heavily influenced by the Chinese government’s political atmosphere in different eras. Materials published in contemporary China often have to go through severe censorship, which makes these materials less trustworthy and less informative, but the good news is that previous editions are often much more informative and helpful. For example, contemporary materials often refrain from mentioning anything about China’s efforts to export revolutions all over the world in the 1960s-1970s because the Chinese government does not like this aspect of its history, but official documents published during the Cultural Revolution often mention this proudly. Similarly, China in the 1980s-2000s was in a more lenient political atmosphere, and thus official materials published in these eras often can reveal more candid and detailed information. Through comparing historical materials published by the Chinese government in different eras, one can use cross-verification to put the puzzles of history together.

In addition to materials published officially by the central government, formerly confidential materials created and circulated at the level of local government can be very helpful as well. For example, in 1973, the Institute on the Religion of Islam of Northwest University of China wrote a book on the Palestinian issue; in 1976, Workers Theoretician Group of the Wuhan Heavy Duty Machine Tool Factory cooperated with Department of History of Central China Normal University to write a book on the history of Palestine; in 1977, the Department of International Politics of Peking University compiled and edited a history of anti-imperialist struggles of the Middle East. These three books were not written by the Chinese central government, but these three books are all listed as confidential reference books for use only within the government. This shows that, although these books may not directly represent the Chinese central government’s will, they had a certain degree of influence within the policy-making groups of China and narratives of these books can at least partially represent the dominant views of the Chinese government and society on the Palestinian issue. Good news for researchers is that these formerly confidential materials in the 1970s can be easily accessed now in vintage bookstores or community libraries in China.

Last but not the least, in order to discover how the Chinese common people saw Palestine in this era, I collected and utilized lots of academic works, literature works, and cultural products created and published at the time that I am studying (1950s-1970s). The aforementioned three books, for example, are some of the academic works in this era that I used for my research. The one written jointly by Workers Theoretician Group and Peking University is particularly important for me: It not only reflects Maoist China’s efforts to bring the proletariat into the intelligentsia, but also shows that the PRC put efforts in popularizing its pro-Palestine foreign policy into all aspects of the society including workers’ workplace.

In addition, the Peoples’ Daily also is a good source helping me to know more about what international events the Chinese government cared about the most in this era, how the Chinese government perceived the world in this era, and what the Chinese government did or claimed that it did to strengthen China-Palestine and China-Arab solidarity in this era. Besides the People’s Daily which is the mouthpiece of the Chinese central state, each province in China also had their official newspaper, which can be very helpful for my research as well. For example, the May 16th, 1969, the date marking the beginning of the Cultural Revolution of China, the Inner Mongolia Daily dedicated an entire page to Palestine, covering China’s military aid to the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and Syria, the PLO’s recent success in guerilla warfare, and commenting on the most recent diplomatic moves of the U.S.S.R and the U.S. regarding the Palestinian national liberation movement.

The largest advantage of official newspapers as a source is that it is very easy for researchers to access, as one can easily find these newspapers either on market or freely on state-run community libraries in China.

Besides state-run newspapers, another type of primary source I prefer to use is historical material officially published by the Chinese state. The PRC and the ruling Communist Party of China (CPC) have a number of affiliated departments and research centers specializing in editing, publishing, and sometimes analyzing archives of the Chinese state and the CPC. Materials published by these departments contain various types of useful historical references, including but not limited to official government documents, heads of states’ public and private speeches, records of important diplomatic events, and letters exchanged between government officials. In the case of my aforementioned research on China-Palestine relations, for example, I collected a number of very useful materials published by the Party Literature Research Center of the CPC Central Committee. This office affiliated to CPC Central Committee edited and published a multi-volume Chronicle of Zhou Enlai: 1949-1976 and Chronicle of Mao Zedong:1949-1976, and these multi-volume chronicles provided a very detailed record on what Mao and Zhou wrote about Palestine in public government documents, what they mentioned about Palestine in public diplomatic speeches, and what they said about Palestine in confidential meetings with foreign high-ranked officials from Palestine, the Arab World, and other Third World countries.

The largest advantage of this type of materials is that it is a great substitution of archives: First, these materials are all published books that one can easily access in either libraries or the markets, and thus one does not need to go through the pain of dealing with the bureaucracy of state-operated archives. Second, these materials are official historical accounts of the Chinese state or the CPC, and thus the credibility of these materials should be regarded as the same as archives stored in the Archives Office of the Foreign Ministry or other state-operated archives.

Of course, just like archives accessed in state-run archives, these materials are also official narratives of history that have gone through selections and censorship, and thus researchers must approach them with critical thinking. I, however, discovered a good way to re-verify these materials: Since these archival departments are part of the Chinese government, their selection and publication of materials are also heavily influenced by the Chinese government’s political atmosphere in different eras. Materials published in contemporary China often have to go through severe censorship, which makes these materials less trustworthy and less informative, but the good news is that previous editions are often much more informative and helpful. For example, contemporary materials often refrain from mentioning anything about China’s efforts to export revolutions all over the world in the 1960s-1970s because the Chinese government does not like this aspect of its history, but official documents published during the Cultural Revolution often mention this proudly. Similarly, China in the 1980s-2000s was in a more lenient political atmosphere, and thus official materials published in these eras often can reveal more candid and detailed information. Through comparing historical materials published by the Chinese government in different eras, one can use cross-verification to put the puzzles of history together.

In addition to materials published officially by the central government, formerly confidential materials created and circulated at the level of local government can be very helpful as well. For example, in 1973, the Institute on the Religion of Islam of Northwest University of China wrote a book on the Palestinian issue; in 1976, Workers Theoretician Group of the Wuhan Heavy Duty Machine Tool Factory cooperated with Department of History of Central China Normal University to write a book on the history of Palestine; in 1977, the Department of International Politics of Peking University compiled and edited a history of anti-imperialist struggles of the Middle East. These three books were not written by the Chinese central government, but these three books are all listed as confidential reference books for use only within the government. This shows that, although these books may not directly represent the Chinese central government’s will, they had a certain degree of influence within the policy-making groups of China and narratives of these books can at least partially represent the dominant views of the Chinese government and society on the Palestinian issue. Good news for researchers is that these formerly confidential materials in the 1970s can be easily accessed now in vintage bookstores or community libraries in China.

Last but not the least, in order to discover how the Chinese common people saw Palestine in this era, I collected and utilized lots of academic works, literature works, and cultural products created and published at the time that I am studying (1950s-1970s). The aforementioned three books, for example, are some of the academic works in this era that I used for my research. The one written jointly by Workers Theoretician Group and Peking University is particularly important for me: It not only reflects Maoist China’s efforts to bring the proletariat into the intelligentsia, but also shows that the PRC put efforts in popularizing its pro-Palestine foreign policy into all aspects of the society including workers’ workplace.

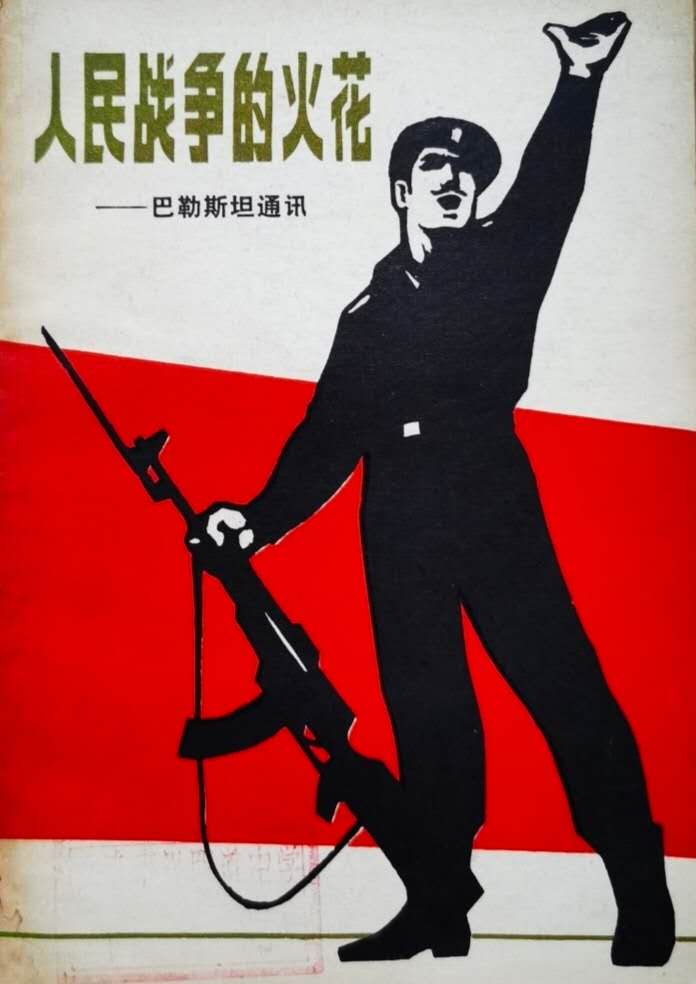

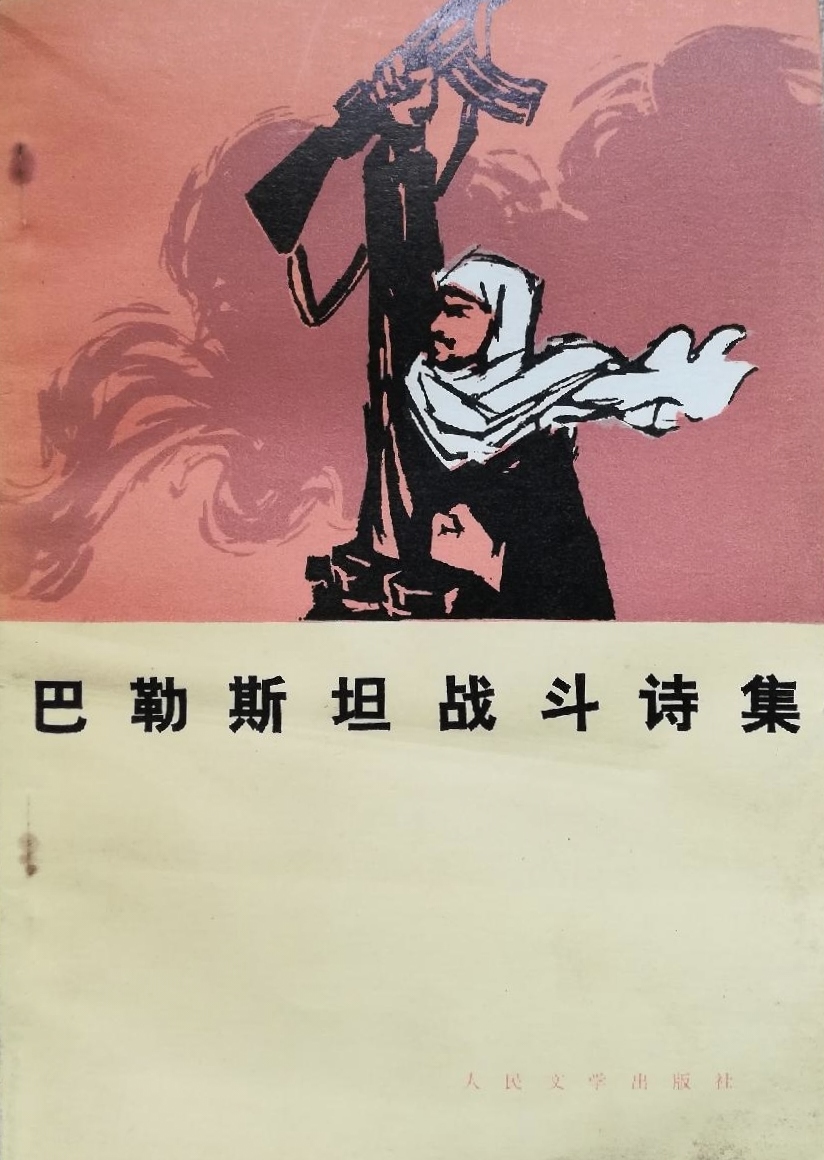

Literature and cultural products are also particularly insightful for my research. In 1971, for example, the Chinese Central Studio of News Reels Production released a documentary applauding armed struggles of the PLO, and this documentary provides a valuable record on how China supported the guerilla warfare of the Palestinian people in political and military ways. As for the literature field, since the 1960s, the PRC not only introduced poems and novels by famous Palestinian writers such as Ghassan Kanafani and Abu Salma into China, but also encouraged Chinese writers to compose works related to Palestine according to their imagination. In 1975, for example, the People’s Literature Publisher published a collection of poems on Palestinian armed struggle, which is compiled with some poems written by Palestinian writers and some poems written by Chinese writers and even common workers.

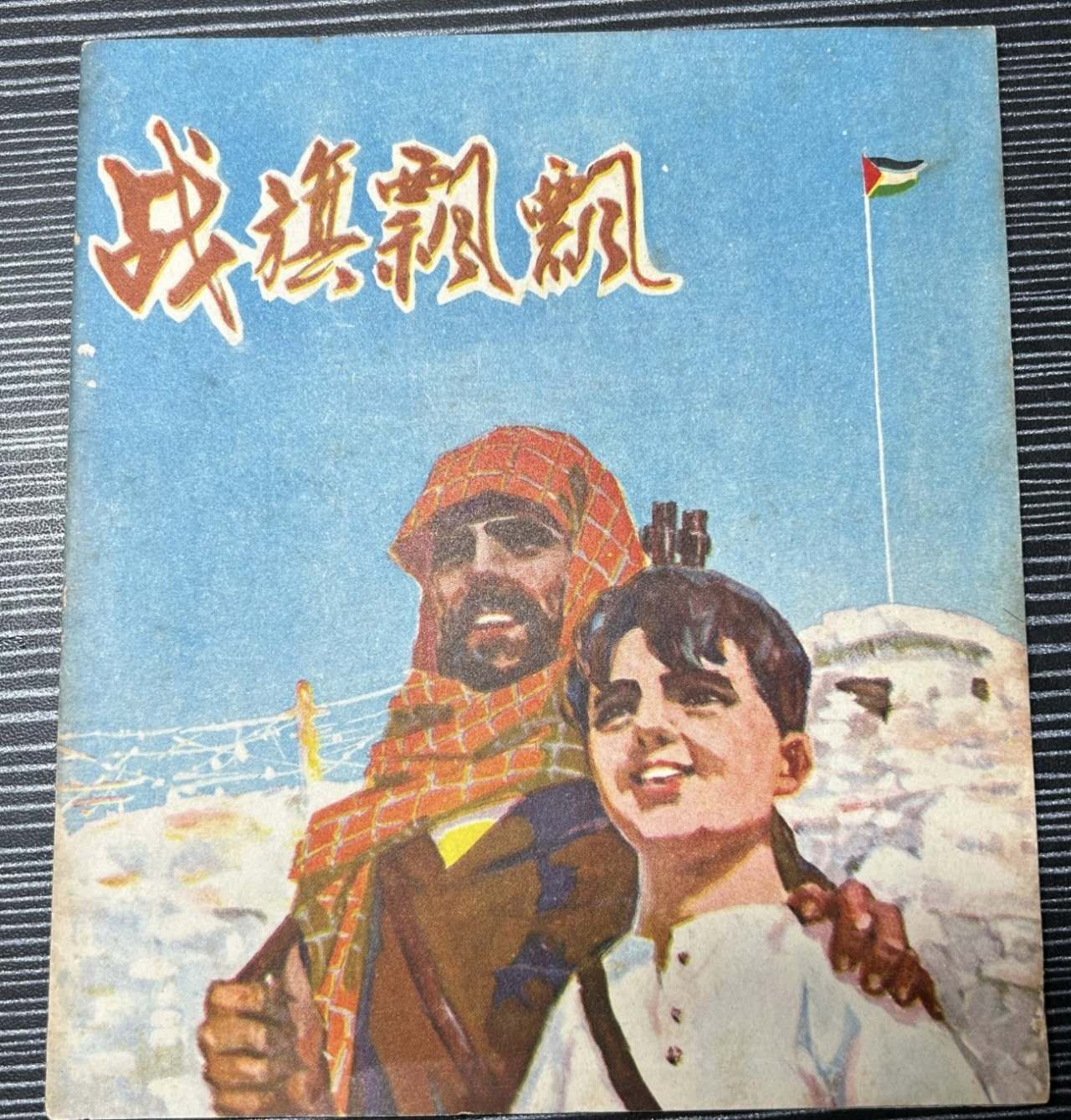

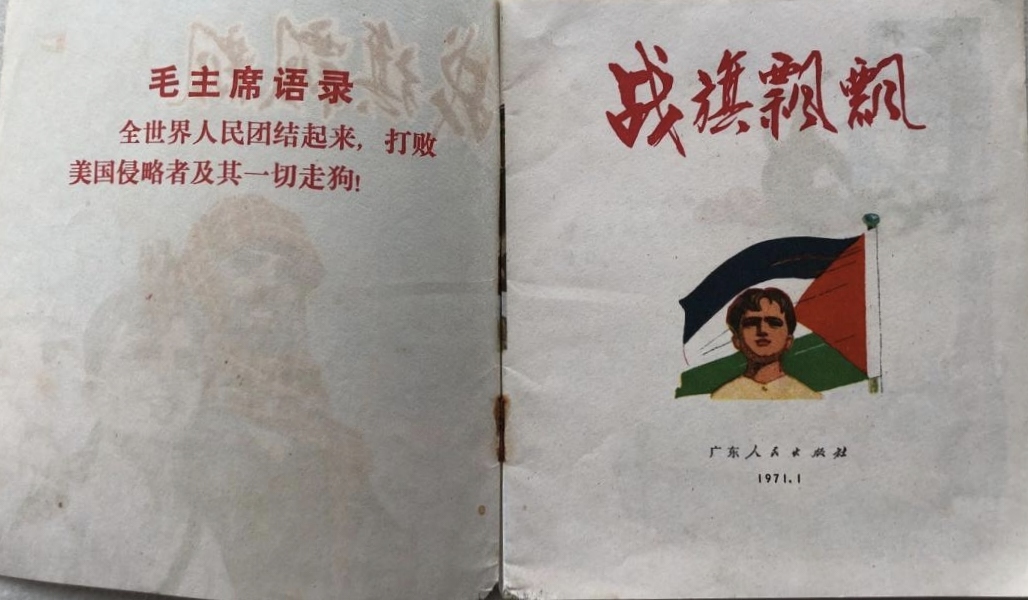

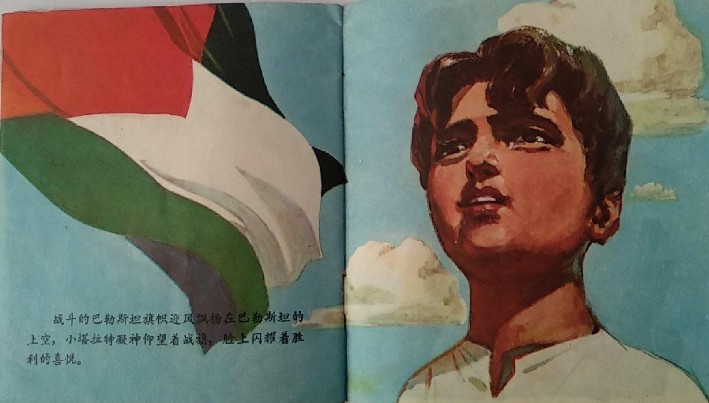

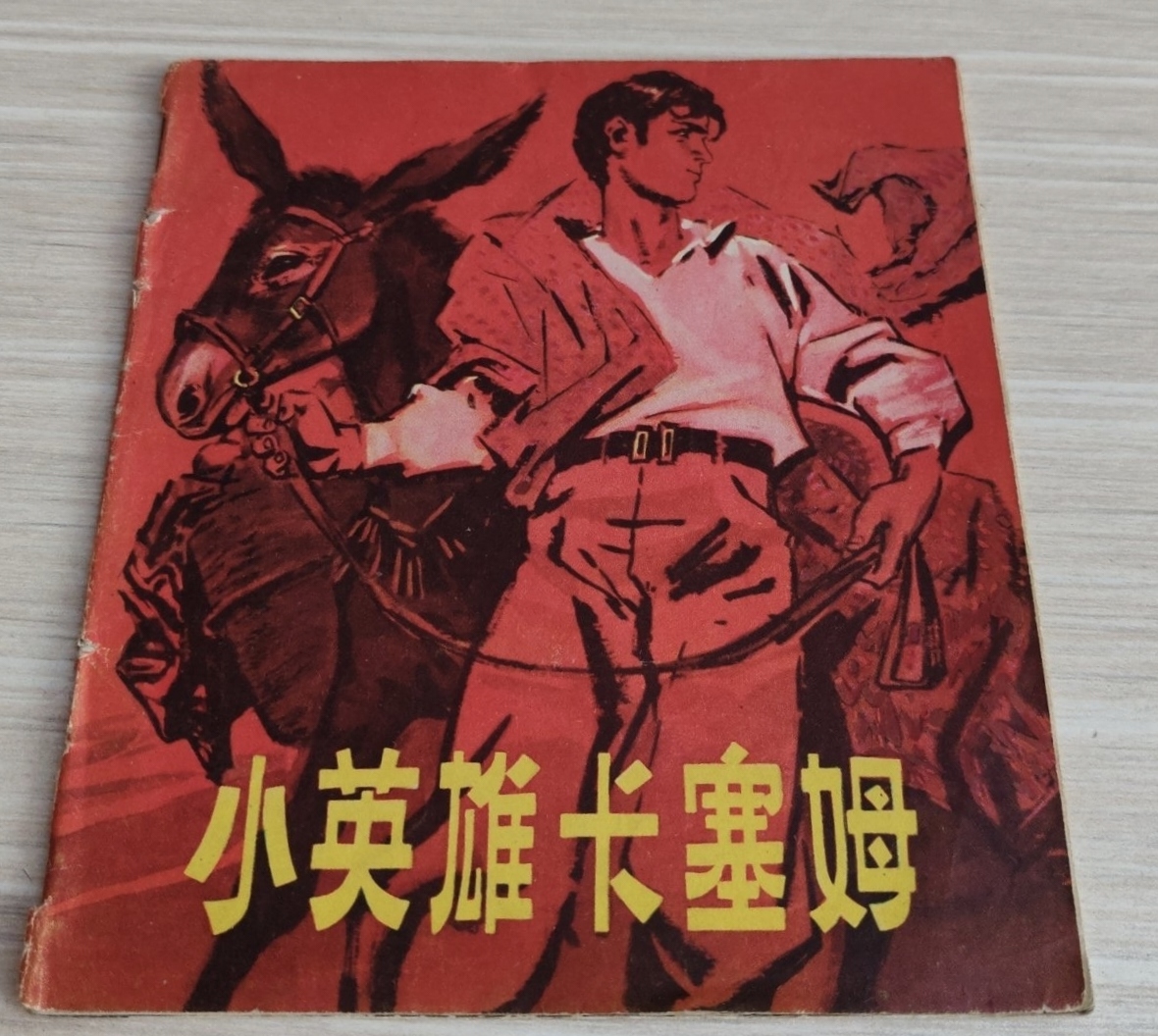

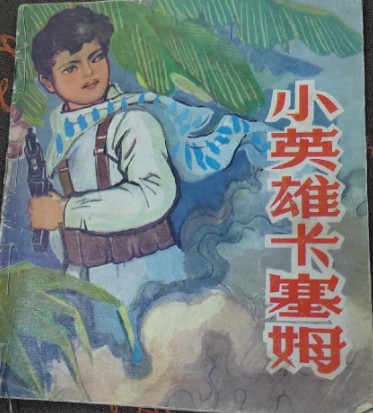

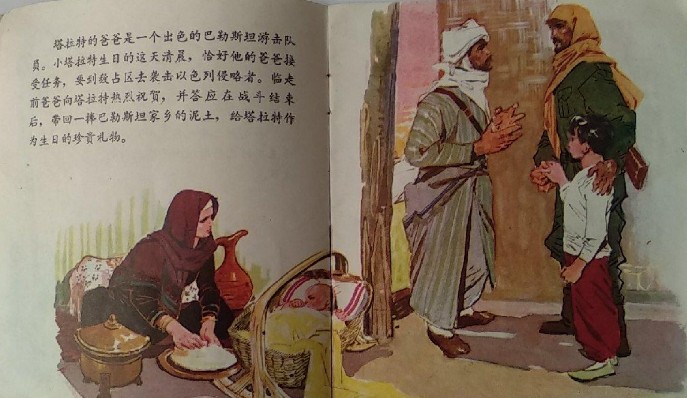

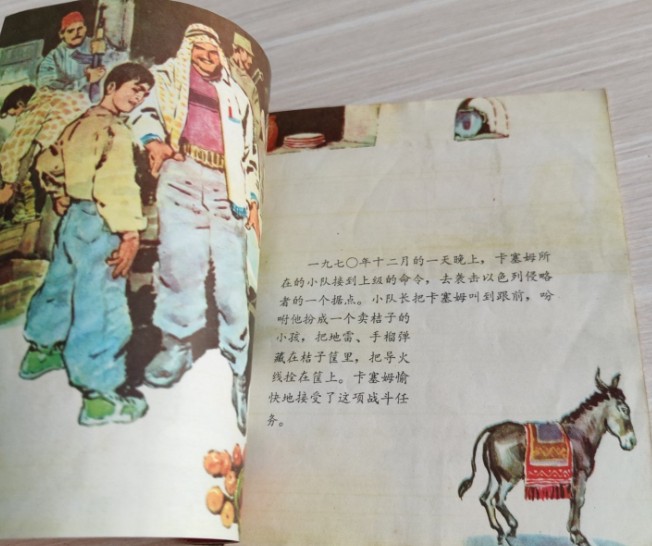

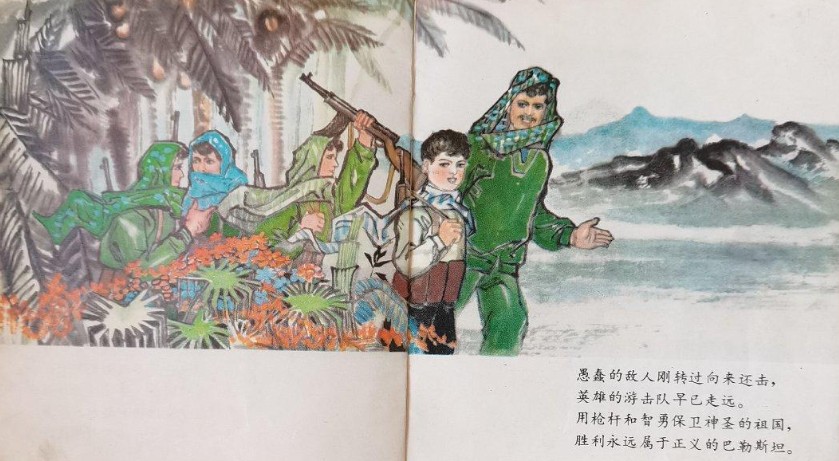

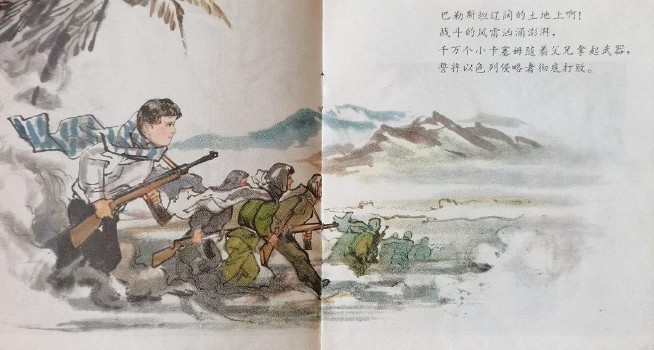

The most interesting finding of mine is that Palestinian armed struggle was even a genre for children’s books in China in the 1970s. In 1971, a state-affiliated publisher in Guangdong composed and published a comic book for children titled The Waving Flag of Combat, and the plot of this book is about a thirteen-year-old Palestinian boy joining guerilla warfare against the Occupation. One year later, in 1972, the same publisher published another comic book for children named Little Hero Qassam, which tells a similar story of how a fourteen-year-old Palestinian refugee boy accomplished a revenge for his late father by tricking the Israeli occupation army into the ambush of the guerilla forces. This book was so popular that one year later, in 1973, little Qassam’s story was re-created into a long poem with paintings by artists from another state-affiliated publisher based in Heilongjiang province. The interesting part of these comic books is that these stories are entirely written by local Chinese children’ book writers, who not only never went to Palestine, but also most likely never even had direct interactions with high-ranked Chinese diplomats of the central government. These Chinese writers’ imaginations of young Palestinian fedayeens was largely based on images of fictional figures of the Chinese revolutionary literature tradition such as Wang Eerxiao or Zhang Ga the Little Soldier, both are fictional boy scouts guerilla fighters based on real prototypes of Chinese children who participated in guerilla warfare against the Japanese occupation during World War II. The existence of these literature and cultural products sheds insightful lights on my research: First, these materials show that the PRC attempted to institutionalize China’s foreign policy domestically through systematic educational and propaganda campaigns, and the scale of such a massive pro-Palestine campaign included even children’s fictional books for leisure time. Second, these materials clearly demonstrates how the Chinese intellectuals and common people established their sense of synchronicity and eventually a sense of anti-colonial solidarity with the Palestinian national liberation movement through imagining Palestine by applying the lens of China’s own historical trauma of foreign occupation and memory of guerilla warfare-based resistance.

Similar to many of the aforementioned sources, literature and cultural products published in the historical period that I conduct research on are also easy for researchers to access, either in vintage bookstores or community libraries in China.

In conclusion, for my own research focusing on diplomatic history of China-Palestine solidarity in the Maoist era (1949-1976), I found two main obstacles: First, it is difficult for a young scholar to get access to state-operated archives, especially archives related to the foreign policy of the PRC; second, since the Chinese state’s official policy is still heavily influenced by the Deng Xiaoping era’s official doctrine delegitimizing everything in the Cultural Revolution era, the contemporary Chinese academia is consequently more or less intentionally shunning away from discussing the Chinese foreign policy in the Cultural Revolution period, especially about the PRC’s efforts of supporting anti-colonial and Maoist insurgencies all over the world.

To circumvent these obstacles, I largely based on research on the following primary sources: Official newspapers affiliated to the Chinese central and local governments, official documents edited and published by the history departments of the Chinese state and the CPC, academic works written and published in historical period that I am studying (1949-1976) or in a later historical period in which censorship was less harsh (1980s-early 2000s), and literature and cultural works created in the historical period that I am studying.

In conclusion, for my own research focusing on diplomatic history of China-Palestine solidarity in the Maoist era (1949-1976), I found two main obstacles: First, it is difficult for a young scholar to get access to state-operated archives, especially archives related to the foreign policy of the PRC; second, since the Chinese state’s official policy is still heavily influenced by the Deng Xiaoping era’s official doctrine delegitimizing everything in the Cultural Revolution era, the contemporary Chinese academia is consequently more or less intentionally shunning away from discussing the Chinese foreign policy in the Cultural Revolution period, especially about the PRC’s efforts of supporting anti-colonial and Maoist insurgencies all over the world.

To circumvent these obstacles, I largely based on research on the following primary sources: Official newspapers affiliated to the Chinese central and local governments, official documents edited and published by the history departments of the Chinese state and the CPC, academic works written and published in historical period that I am studying (1949-1976) or in a later historical period in which censorship was less harsh (1980s-early 2000s), and literature and cultural works created in the historical period that I am studying.

Sheng Zhang

ZHANG Sheng is a non-resident visiting researcher at the Center for Asian Studies (KUASIA), Koç University, Türkiye. Zhang’s research interests include, but are not limited to, the evolution and transformation of China’s engagement in the Middle East, China's historical relationship with anti-colonial movements in Palestine and the Arab World, and Chinese diplomacy and politics from the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 to the present. In addition, Zhang is a research fellow affiliated with several think tanks and research institutes in China and Nepal. Beyond his academic career, he is also a political commentator and columnist, frequently contributing opinion pieces and giving television interviews for various mainstream media outlets in China, Egypt, Russia, and Nepal.

ZHANG Sheng is a non-resident visiting researcher at the Center for Asian Studies (KUASIA), Koç University, Türkiye. Zhang’s research interests include, but are not limited to, the evolution and transformation of China’s engagement in the Middle East, China's historical relationship with anti-colonial movements in Palestine and the Arab World, and Chinese diplomacy and politics from the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 to the present. In addition, Zhang is a research fellow affiliated with several think tanks and research institutes in China and Nepal. Beyond his academic career, he is also a political commentator and columnist, frequently contributing opinion pieces and giving television interviews for various mainstream media outlets in China, Egypt, Russia, and Nepal.