Onyeka Igwe

Lodging in anti-imperial London

Funmilayo Ransome Kuti arrived in Southampton by boat on 10 July 1947. She was coming from Abeokuta in Southwestern Nigeria where she was teacher and leader of A teacher’s union, wife of a reverend and mother to four children who were schooling in the UK and U.S. She had been imprisoned earlier in the year for her involvement in the Egba market women’s protests and refusal to pay taxation, which was not traditionally paid by women, to the British state.1 She came to London to form part of the seven strong National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons delegation to petition for Nigerian independence. This was a London that was surfeit with anti-colonial fervour. Organisations made up of people from across the British Empire at that time, like the International African Service Bureau, League of Coloured People, West African Students Union, West African National Secretariat, India League and All Subject Peoples conference were agitating for the end of colonial rule using a variety of repertoires.2 From publishing, to speeches, political organisations, to poetry, theatre and social gatherings.

1. For more see Byfield, Judith A., ‘Taxation, Women, and the Colonial State: Egba Women’s Tax Revolt’, Meridians, 3.2 (2003), pp. 250–77

2. See Younis, Musab, On the Scale of the World: The Formation of Black Anticolonial Thought, 1st edn (University of California Press, 2022), Williams, Theo, Making the Revolution Global: Black Radicalism and the British Socialist Movement before Decolonisation (Verso Books, 2022), Matera, Marc, Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century (University of California Press, 2015) and Adi, Hakim, West Africans in Britain, 1900-1960: Nationalism, Pan-Africanism, and Communism (Lawrence & Wishart, 1998)

2. See Younis, Musab, On the Scale of the World: The Formation of Black Anticolonial Thought, 1st edn (University of California Press, 2022), Williams, Theo, Making the Revolution Global: Black Radicalism and the British Socialist Movement before Decolonisation (Verso Books, 2022), Matera, Marc, Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century (University of California Press, 2015) and Adi, Hakim, West Africans in Britain, 1900-1960: Nationalism, Pan-Africanism, and Communism (Lawrence & Wishart, 1998)

Thirty-four years later, June Givanni, a recent master’s graduate, was employed by the Ethnic Arts subcommittee of the Greater London Council’s Arts and Recreation Committee. This was the 1980s when London was governed by a socialist leadership that attempted to redress a political climate of rising fascism, racial divisions and a spate of riots across racialised communities in the United Kingdom most notably in Brixton and Handsworth, and Birmingham. The recently realised committee alongside its sister subcommittee, Community Arts was tasked with promoting culture that came out of grassroots marginalised communities. Stella Dadzie described these communities as immersed in an anti-imperial politic, where solidarity around a conceptualisation of diverse ethnic groups united by their experiences of British colonialism created an identity - political blackness.3 The Ethnic Arts subcommittee was steered by Parminder Vir and together with June they devised a film festival, Third Eye: London Third World Film Festival that would propose film as a liberatory tool and showcased films from across what was then described as the Third World introducing radical Third Cinema filmmaking to a London audience.

3.

Dadzie, S. (2023) ‘Black British Womanhood, Politics and Organising’, Race & Resistance . Stella Dadzie : Black British Womanhood, Politics and Organising, Oxford : United Kingdom , 17 November.

These events make up a part of London’s long standing and extensive anti-imperial and internationalist history. A London that I feel deeply at home in, familiar with, an identity I eagerly take up in contrast to the other labels of British or Nigerian that hang limply to my identity. A London that many friends are leaving because of an island mentality heightened by Brexit and the recent but habitual rise of fascism on the country’s streets. It is a history that I wanted to fortify me in the current conjecture. So, over the past 3 years I lodged in these pasts. Concurrently working on two different archival projects, both inspired by London as a ground for internationalism, and specifically third world political solidarity.

The first A Radical Duet, was a film and subsequent exhibition imagining a meeting of early 20th century pan-African activist luminaries.

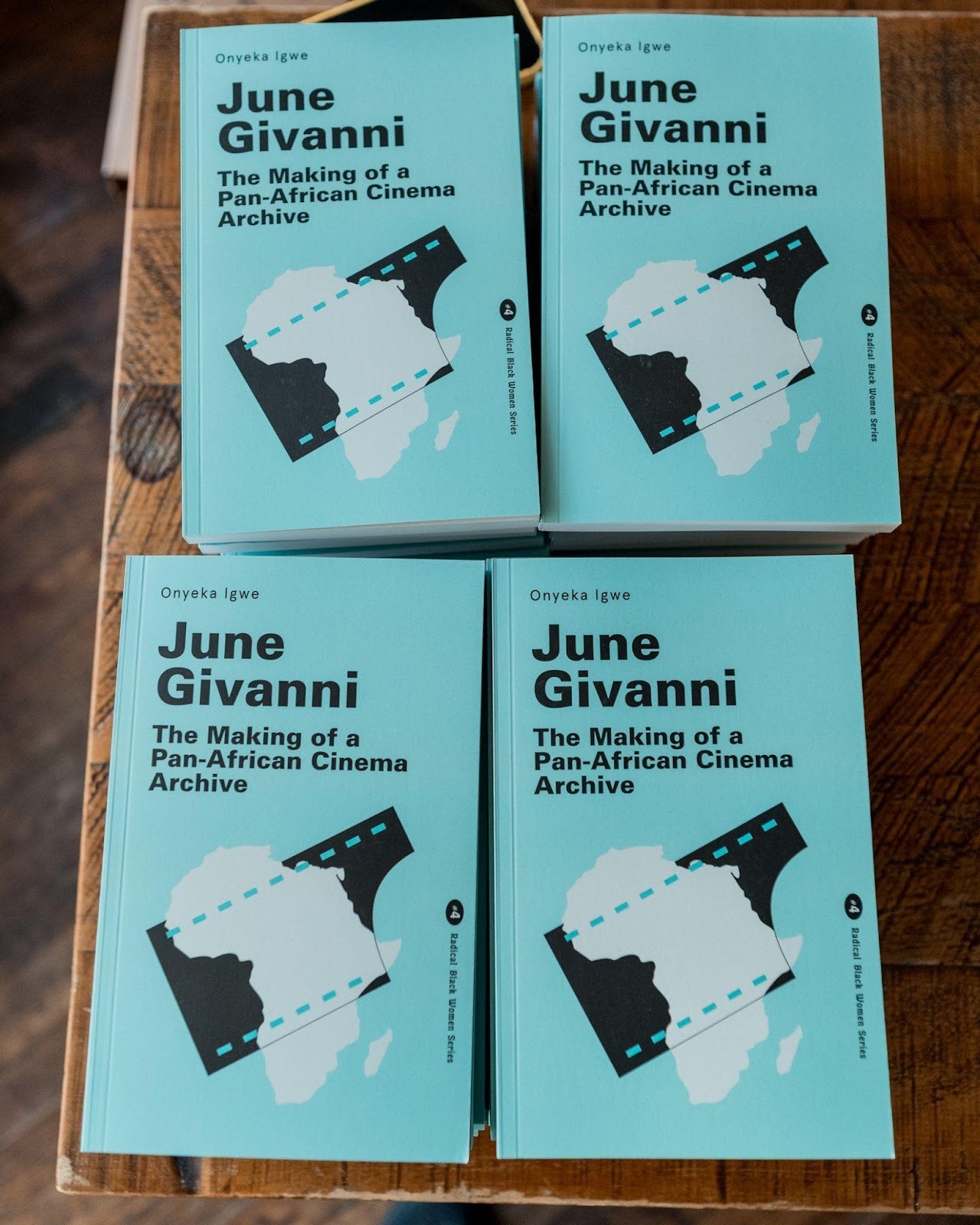

The second was a book, June Givanni: The Making of a Pan-African Cinema Archive on the creation of a counter archive of British cinema which was founded in the milieu of 1980s London anti-imperialist organising.

The first A Radical Duet, was a film and subsequent exhibition imagining a meeting of early 20th century pan-African activist luminaries.

The second was a book, June Givanni: The Making of a Pan-African Cinema Archive on the creation of a counter archive of British cinema which was founded in the milieu of 1980s London anti-imperialist organising.

Incidentally, both works have Pan-Africanism as central to their conceits. I never considered myself as a Pan-Africanist and would instead shy away from the term. So, this new orientation was surprising to me. I came to, through working on these projects, understand Pan-Africanism differently than the essentialising Africanist versions of it I had mostly experienced at this point. I came to understand it as an opposition to the totalising western nation state formations that coalesced in Africa as the imaginary of an elsewhere that could mobilise these anti-imperial visions.

As an artist working with political questions through historical enquiry, in using archives to make work, I define them as broadly and widely as I can. Archives, yes are those uptight institutions that forbid pens in their reading rooms like The British National Archives in Kew. But there are also songs, gossip, food, folk tales, smells, half remembered conversations, nature, imagined sounds and the cornices in the doors of buildings that have stood for decades. I used all these archives to make these projects.

As an artist working with political questions through historical enquiry, in using archives to make work, I define them as broadly and widely as I can. Archives, yes are those uptight institutions that forbid pens in their reading rooms like The British National Archives in Kew. But there are also songs, gossip, food, folk tales, smells, half remembered conversations, nature, imagined sounds and the cornices in the doors of buildings that have stood for decades. I used all these archives to make these projects.

The Film

In my research for the film that would become A Radical Duet I came across this passage in the CLR James biography about a day he spent in Bloomsbury in the 1930s.

“He had a lie-in in the morning, reading the newspapers and weekly magazines, a highlight being 'the delightful Miss Rebecca West in the Daily Telegraph'. At lunchtime he set off for Middle Temple, to meet two friends and spend time walking and arguing and stopping in cafès till six, when he headed over to the Society for International Studies. There he delivered a lecture (on what, he does not say). That done, he says, you might think that was enough for one day. You simply do not know Bloomsbury! No indeed. After the lecture, CLR and a party of friends went to the Russell Square tube café just before midnight to talk and drink coffee. He might have eaten too, except the president of the Friends of India society invited him to come for dinner at a friend's house half a mile away (of this dinner he notes, somewhat surprisingly; how lithe the average middle-class English person seems to drink). They talked about art for hours. CLR got to see 'a reproduction of some Pompeian wall paintings which I had heard about and wanted to see', before leaving at around four in the morning. His Indian friends then went to the all-night post office to send an airmail, but CLR actually called it a night.”4

4.

Williams, John L., CLR James: A Life Beyond the Boundaries (Constable, 2022) p.81

It fizzed for me because it reminded me of something of my own contemporary life. I always stupidly can't believe that people live the same lives over and over - it felt vital to understanding the mindset of the type of characters the film was about. People who were living internationalist lives in London. So, I needed to visit these streets and retrace some steps. I loved imagining James’ day and then thinking that the buildings he spent time in are still here (well most), that they've been under my nose and that they could be a way to access these moments or memories. The buildings are remainders.

Following the below instructions, I went back to these streets to observe the things that remain from the radical, anti-colonial, contrapuntal London of the early twentieth century.

I repeated this exercise in different locations, the streets of Bloomsbury that CLR James traversed in, the lodgings that Funmilayo Ransome Kuti stayed with the rest of the delegation, the site of Africa House where the West African Student Union was stationed and the former residences of George Padmore and Sylvia Wynter. Sometimes I was alone, with a friend, with a notebook, with a sound recorder, with a 16mm camera, with my phone.

Following the below instructions, I went back to these streets to observe the things that remain from the radical, anti-colonial, contrapuntal London of the early twentieth century.

Go to a site, touch its surfaces, touch the ground.

Close your eyes and listen to your body, its surfaces.

Listen to the space around you. Try to name all the sounds you are hearing.

After 2 minutes, open your notebook and spend 2 minutes writing down what you heard.

Record sounds.

I repeated this exercise in different locations, the streets of Bloomsbury that CLR James traversed in, the lodgings that Funmilayo Ransome Kuti stayed with the rest of the delegation, the site of Africa House where the West African Student Union was stationed and the former residences of George Padmore and Sylvia Wynter. Sometimes I was alone, with a friend, with a notebook, with a sound recorder, with a 16mm camera, with my phone.

Some reflections of these experiences made it into the film, but most of them split over what the film could contain and simply enriched the world I was creating through my imagination or deepened the understanding I was developing of this history in ways that language delimits. They continue to have resonance without my direction.

The Book

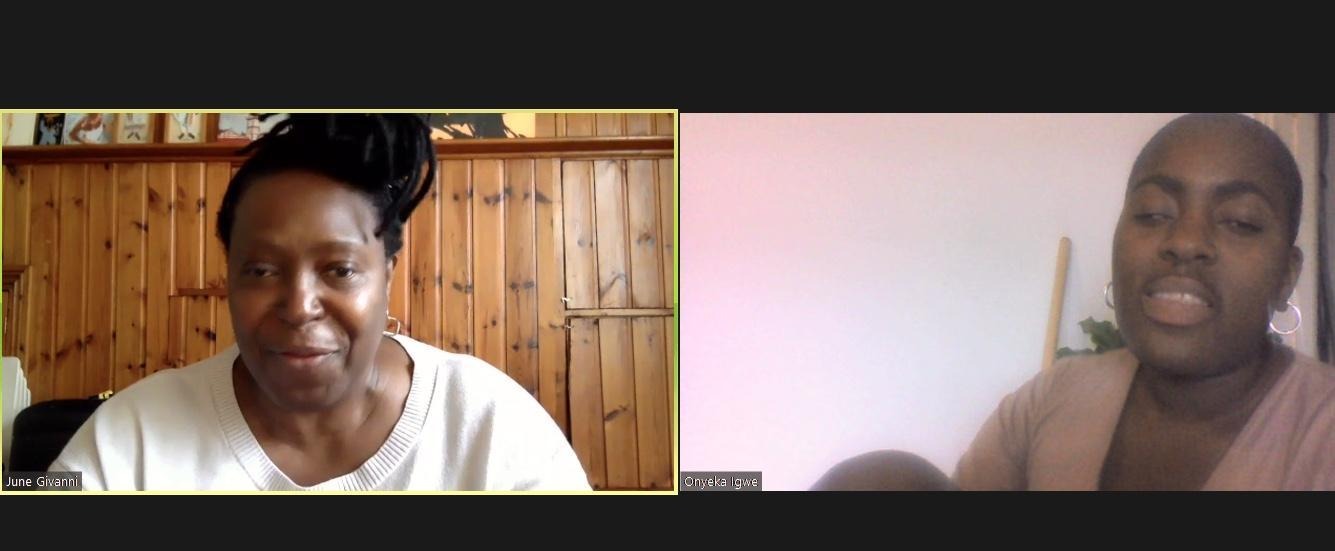

Writing something of a biography of an archive means the Derridean impulse looms even larger with the temptation to return to the source. I was writing a history of an institution run by someone I knew, was in contact with and had a working relationship. I had met the archive’s namesake, June Givanni in 2016 and since then we have co-written texts together, ran workshops, attended events and swapped hosting duties for screenings and talks several times over. So, it was easy to speak to her in order to research the work that she did which founded the archive.

The June Givanni Pan-African Cinema Archive (JGPACA) is made up of films, film festival ephemera, texts, correspondence and more from over forty years of a career programming pan-African cinema worldwide. The archive spans all continents (save Antarctica) and holds a cast of filmmakers past and present who go from household names to long lost directors ripe for rediscovery. I wanted too, to talk to these people, the vast interconnected network of film workers that constitute the community of the archive. Many had died and were dying as I wrote the book so sometimes it felt like a macabre race, I didn't want to be in. Others were frail or ill and didn't think their memories were up to my inquisition. I was sensitive to the way my request could feel like selfish demand. Some people I approached refused without explanation, allowing my mind to wonder about what events of the past that meant talking to me was impossible or to puzzle over whether people should be paid for these intrusions into their time. Most said yes because of their friendships with June and respect for her and her work. It felt like fidelity was all I could offer in return, I wanted to be as true as possible to whatever they said, quoting verbatim and never fact checking a memory.

I interviewed people in person when I could in some of the only places in the city you can meet for free at the Royal Festival Hall or the Barbican. The ways we arrived at the locations weaving its way into conversation so that I remember one conversation mostly for the reboot joke when I told the sole of my shoe was causing a delay in my arrival. The majority of interviews were conducted on Zoom where the dialogue through screens didn't dim the intimacy and with a fewer number I used the ancient technology of a telephone call. I remember where I was sitting at Glasgow train station interrupted consistently by announcements over the tannoy when I finally managed to speak to the octogenarian artist I had been chasing for weeks.

My interviewees were more than generous, allowing me to peek into moments in their histories. I inevitably ended each call buoyed, scheming on how I could take on the model of their late twentieth century internationalism into my present. Did I need to facilitate an updated Third Eye Film Festival or adopt the collective filmmaking frameworks of old? Did I need to leave my job at a university and find new ways to contribute to the struggle? Did I need to question Pan-Africanism or adopt it wholesale? Was the upcoming edition of FESPACO5 bound to disappoint or be the fountain of a reinvigorated pan-African film movement? What did it mean today to make political films?

5.

Pan African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou

And so, these works were made – A Radical Duet screened in niche film festivals worldwide and spilled over into three exhibitions in galleries in London, Nottingham and Montreal whilst June Givanni: The Making of a Pan-African Cinema Archive was published by Lawrence & Wishart in their Radical Black Women series available in bookstores and university libraries. I think about audiences and who can now access these histories I was previously ignorant of. I think about whether this film that utilises fiction instead of historical fact fulfils a responsibility to educate. I think about whether my small delve into the history of JGPACA rooted in my subjective experiences of the archive and limited to the 1980s is enough of an incentive for people to ask further questions. And then I remember I think of my work as an offering to begin where we begin.

Onyeka Igwe

Onyeka Igwe is a London born & based moving image artist and researcher. Her work is aimed at the question: how do we live together? Not to provide a rigid answer as such, but to pull apart the nuances of mutuality and co-existence in our deeply individualized world. Onyeka’s practice figures sensorial, spatial and counter-hegemonic ways of knowing as central to that task. She is interested in the prosaic and everyday aspects of black livingness. For her, the body, archives and narratives both oral and textual act as a mode of enquiry that makes possible the exposition of overlooked histories. The work comprises untying strands and threads, anchored by a rhythmic editing style, as well as close attention to the dissonance, reflection and amplification that occurs between image and sound.

Onyeka’s video works have been screened at Modern Mondays, MoMA, Artists’ Film Club: Black Radical Imagination, ICA, London, 2017; Dhaka Art Summit, Bangladesh, 2020, and at film festivals internationally including the London Film Festival, 2015 and 2020; Open City Documentary Film Festival 2021 and 2022, Rotterdam International, Netherlands, 2018, 2019 and 2020; Edinburgh Artist Moving Image, 2016; Images Festival, Canada, 2019, and the Smithsonian African American film festival, USA, 2018.

︎︎

Onyeka Igwe is a London born & based moving image artist and researcher. Her work is aimed at the question: how do we live together? Not to provide a rigid answer as such, but to pull apart the nuances of mutuality and co-existence in our deeply individualized world. Onyeka’s practice figures sensorial, spatial and counter-hegemonic ways of knowing as central to that task. She is interested in the prosaic and everyday aspects of black livingness. For her, the body, archives and narratives both oral and textual act as a mode of enquiry that makes possible the exposition of overlooked histories. The work comprises untying strands and threads, anchored by a rhythmic editing style, as well as close attention to the dissonance, reflection and amplification that occurs between image and sound.

Onyeka’s video works have been screened at Modern Mondays, MoMA, Artists’ Film Club: Black Radical Imagination, ICA, London, 2017; Dhaka Art Summit, Bangladesh, 2020, and at film festivals internationally including the London Film Festival, 2015 and 2020; Open City Documentary Film Festival 2021 and 2022, Rotterdam International, Netherlands, 2018, 2019 and 2020; Edinburgh Artist Moving Image, 2016; Images Festival, Canada, 2019, and the Smithsonian African American film festival, USA, 2018.

︎︎