Inkyfada

Making a historical series on colonial surveillance archives:

The case of "Suspicious People".

In this text, the author and the editor of the series of articles

“Suspicious People” look back at the genesis, the writing and the production of

the series within the Tunisian media inkyfada.

Arwa’s part:

One of my favourite spots in Tunis is the National Archives. I love the feeling I get when I wait for the archive file I requested to arrive. When I see it coming, it starts to materialize and I feel a great sensation of joy. I like to touch the folder and its files, to smell it, to be attentive to its fragility.

It is in the National Archives where I discovered, 3 years ago, the archives “Gens suspects” (Suspicious people). The name attracted my curiosity so I dove into these records. I was fascinated by what I found. After a while, I suggested to the independent Tunisian investigative media inkyfada to create a series based on it.

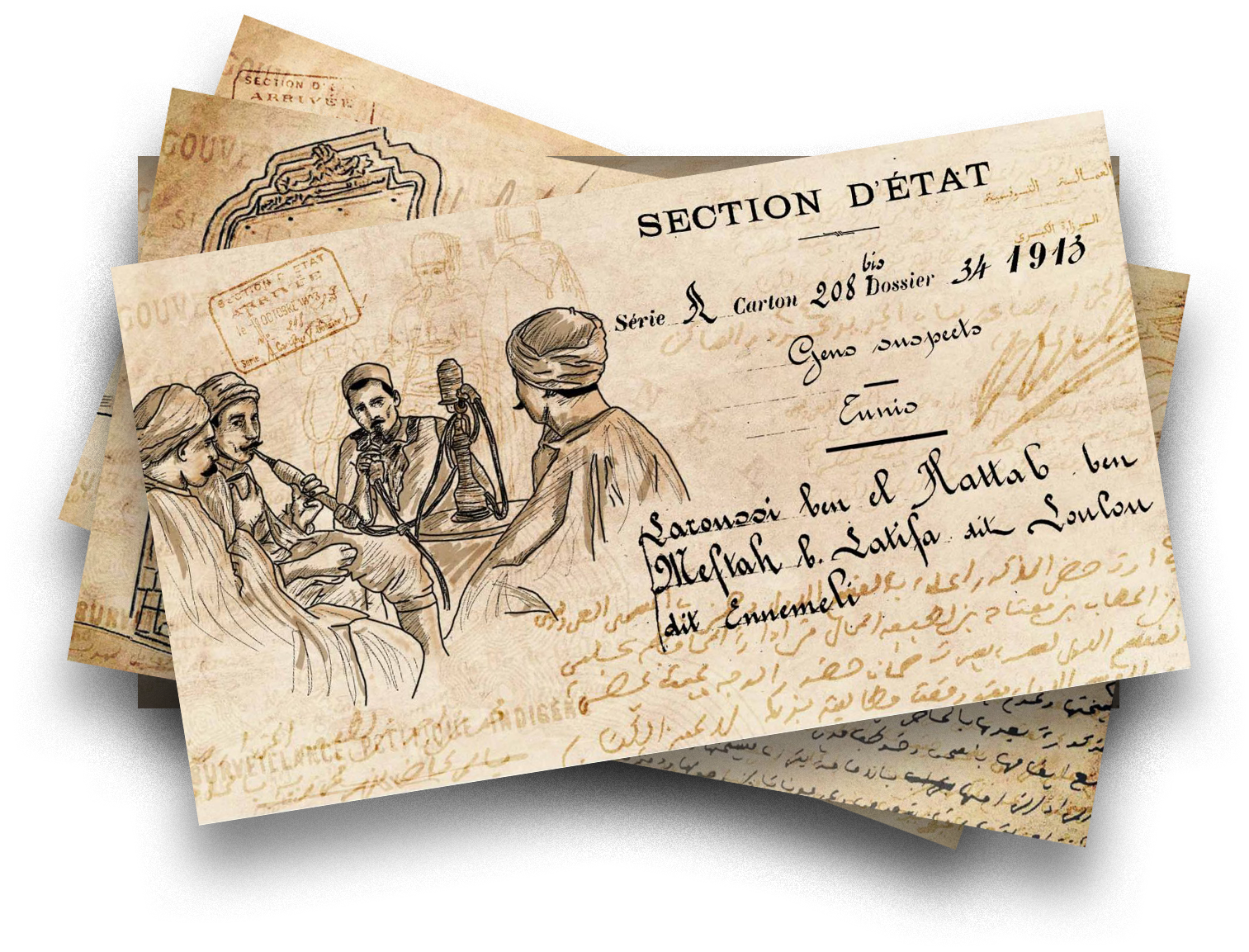

The records consist of 4000 files of people surveilled by the French intelligence services between 1910 and 1930. The files, now kept in the National Archives of Tunisia, and which were handed over after the Independence, include diverse records of men, women, Muslim or Jewish Tunisians, Ottomans, Europeans, etc.

These archives were established during the French Protectorate in Tunisia (1881 - 1956). In particular, they were produced during the state of siege which was decreed in 1911 following the events of Djellaz (one of the first Tunisian large-scale anti-colonial insurrections) and which lasted 10 years including the First World War. During this time, the movements of the local population were extremely controlled and surveillance became systematic.

The period is particularly interesting since, despite the oppressive regime, it witnessed the emergence of the first anti-colonial movements: distribution of leaflets, development of critical or satirical newspapers, creation of clandestine networks of struggle inside and outside urban areas, etc. During the state of siege, individuals under surveillance were mainly targeted because of their political involvement, their criticism of colonization or sometimes even for simply attending a meeting or buying a suspicious newspaper. Some were also watched because of moral reasons or because they were considered as marginal. Surveillance was also often carried out in collaboration with certain locals (indicators or administrative agents).

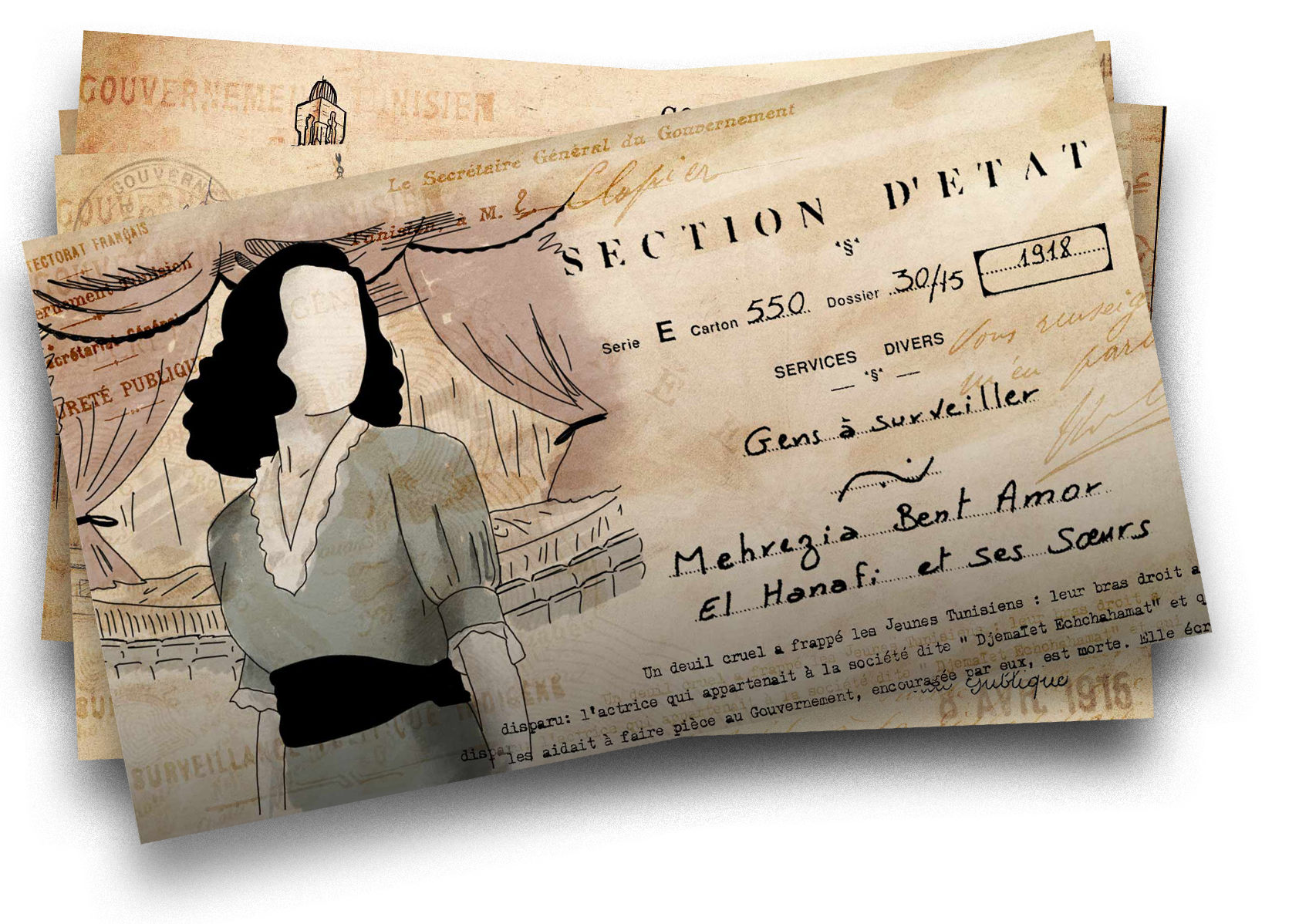

Almost everything was considered suspicious: female engagement, intellectual production, political organization, sex work, artistic expression, etc. In other words, anything that relates to local agency that can potentially challenge the dominant order.

For inkyfada, I investigated and recounted 12 stories from the archival records. This has resulted in a series that bears the same name “Suspicious People”. Out of the 12 portraits, 5 were women. It was a deliberate choice to include a significant proportion of women although it is not a representative figure. Indeed, out of the 4000 cases, there are actually less than 50 women. Through this series, I intended to highlight the female presence in Tunisian history at the beginning of the 20th century in order to counter the national narrative stating that women are mere helpers to men in nationalist movements or that their supposed invisibility in the public space made them politically inactive.

The records reveal the different layers of domination on which the colonial system was based: hierarchy between Europeans and Tunisians, men and women, people from rural areas and people from the city, etc. My aim was to understand the systematic aspects of repression but also to reflect on the different treatments between social groups. Lastly, through these archives, we can see how the legacy of colonial policing practices remains present through surveillance, the disregard for the working classes, arbitrary arrests, etc.

Throughout the making of this series, I felt the need to tell the stories of those arrested by the colonial police. Despite the frustration of having only the authorities’ point of view in the archives, I tried to give the best possible account of what was happening to the people under suspicion.

I would imagine how the suspected or arrested person felt, physically and emotionally. I felt like I was using what I would feel for them, the anger, the sadness or the bitterness as material for the writing, as a kind of fuel.

One of the times this feeling of closeness was very strong was for the article on Mabrouka bent Salem. It was about a woman who was under surveillance because of her ambiguous gender identity (according to the authorities) and because she was carrying suspicious letters. In her file, I came across the letters she was carrying and I was moved to touch them, to smell them. I was touched to know that these were the last letters she transported before her arrest and death in prison.

In the work on “Suspicious People”, we started a reflection within inkyfada on the material dimension of the archives. Our concern was to find ways to make these archives accessible to the public. Haïfa’s input and insights have been very precious in every episode.

Haïfa’s part:

At inkyfada, when Arwa proposed the subject of Suspicious People, we were immediately extremely enthusiastic. I found it fascinating to be able to tell the stories behind these archives, which are little known to the public.

It allowed us to delve into the lives of those under surveillance during the colonial era while at the same time looking at the dynamics of surveillance. Several reasons for surveillance (homosexuality, political opposition, cannabis use, etc.) mentioned in “Suspicious People” are still condemned today. This work of history thus strongly echoes several themes that we address in our journalistic work at inkyfada.

While working with Arwa, my concern, as an editor, was that these stories are told in the best possible way, while keeping the historical component. This included both the text and the documents. Very quickly, the collaboration was established. Arwa began by carefully sorting through the archives. She would send a selection to our designers who would style them and create an illustration image while we both worked on editing the article.

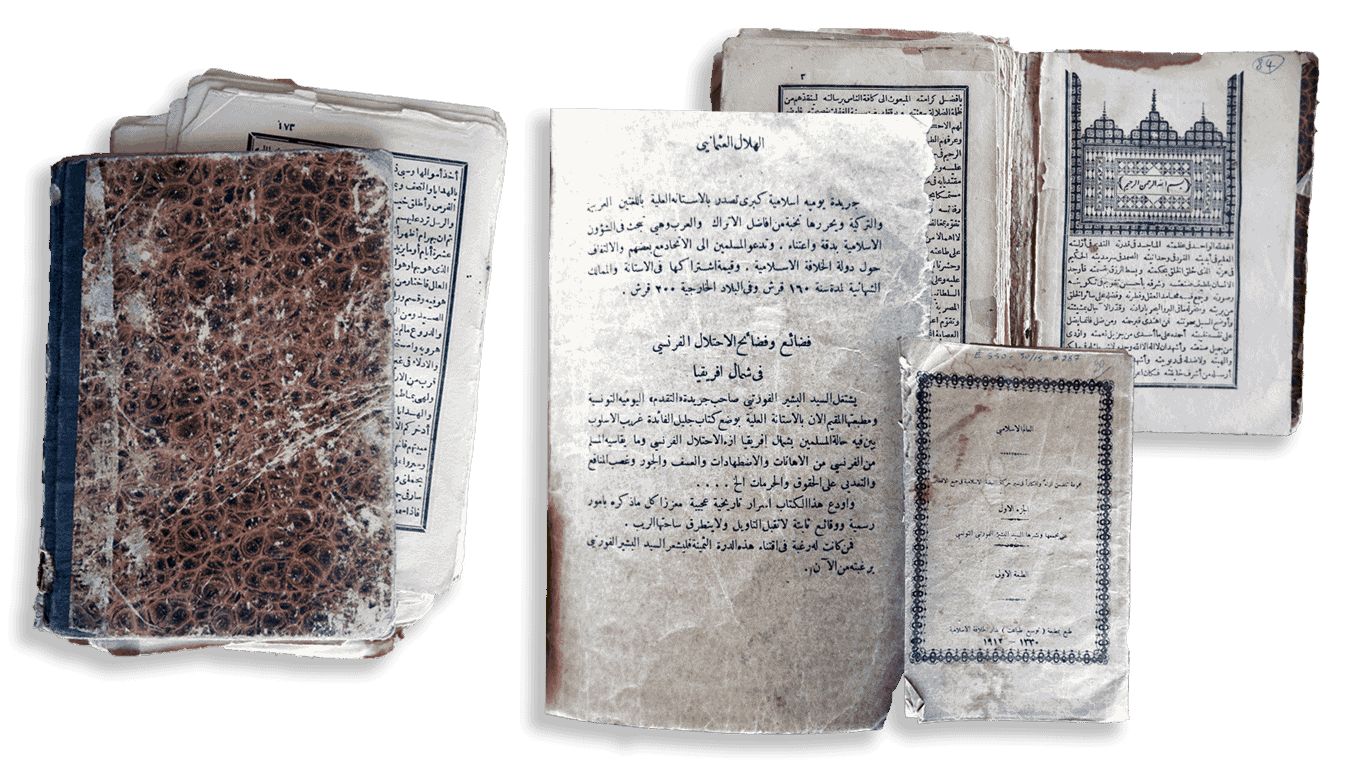

For each portrait in “Suspicious People”, images of archival documents appear. Instead of just describing their contents, we wanted to show them. The reader can see if the surveillance documents are handwritten, typed, in what language they are written, etc. An attentive reader will recognize the signature of the police officer Clapier, which appears in many stories. At inkyfada, we felt it was important that these archives be brought to the forefront, both for their content and their nature. They are the primary source of this work, from an editorial point of view but also for the visual identity of the project.

In parallel to the processing of the documents, we had many discussions about the illustrations of the project. It was relatively easy to define the visual identity. For these historical accounts, we opted for a sepia style, reminiscent of the look of the archives.

But we thought long and hard about the representation of the protagonists. Without photos, with very few descriptions, it was difficult to represent the characters without falling into stereotypes. Once again, the archives were useful. Arwa was looking for photos, illustrations or engravings of the time that could inspire us and help us imagine the outfits of the time for example.

For us, this project is a way

to uncover stories, on an individual scale, that speak volumes about

colonization and France's colonial surveillance practices. It seems essential

to us to tell this history and the legacies that result from it to as many

people as possible. This is why this project has been published in inkyfada media in French and has been translated into Arabic. An English translation is also

planned. Thanks to the series “Suspicious People”, 12 people who existed, for

most of them, only in an archive, have briefly come to life.

Suspecte n°1 :

Mabrouka bent Salem ben Younès.

Suspecte n°2 :

Ahmed El Mechergui.

Arwa Labidi is a Tunisian historian. She received her PhD from the University of Paris Nanterre (France). She is currently assistant professor at the University of Jendouba (Tunisia).

She is the author of two series of historical investigation for the media inkyfada: Gens suspects (Suspicious People) and Le Dessous des dates (Beyond The Dates). Her research focuses on archives, national narratives, minorized histories and education.

Arwa also runs regular urban tours of Tunis, focusing on the city's social, cultural and architectural history.

Haïfa Mzalouat is a journalist and editorial manager for the French version of inkyfada, a Tunis-based investigative medium that produces long-form articles. She studied history, Arabic and political science. She has carried out numerous investigations, notably for the international Pandora Papers investigation, in partnership with ICIJ. Her favorite subjects are migration and historical articles. She edited the historical series - Beyond the dates and Suspicious People - produced by historian Arwa Labidi and published on inkyfada.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎

Inkyfada is an independent, nonprofit media group founded in 2014 by a team of journalists, developers, and graphic designers with the goal of supporting the public interest through innovative journalistic content.

With a particular focus on investigation, contextualization, and data visualization, Inkyfada produces content that helps a diverse readership understand and engage in the politics that impact their lives. Constructed with ongoing collaboration between journalists, developers, and graphic designers, Inkyfada’s publications offer readers accessible and enriching content.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎ ︎