Bayan Haddad

My Mum’s Diary

1.

This is part of an intervention in a series titled Radical Fridays organised by the Institute of Palestine Studies. Professor Roger Heacock’s remarks here are in part II of a conversation about the first intifada under the title of The Radical University and was convened via Zoom on 11 June 2021. The full conversation can be found here.

I grew up viewing Palestinian history in an episodic (and often defeatist) manner – 1948, 1967, first intifada, second intifada and Israel’s wars on Gaza. With the ongoing genocide, there has been a shaking sensation of one’s understanding of temporalities. With more focus now on looking at the Nakba as an ongoing process and not a singular event, many feel stuck and experience time as severely ruptured and radically suspended. Whilst perpetuating a disorienting state in the present moment, colonial powers depend on amnesia.

Indeed, there has been what professor Roger Heacock calls an “epistemological break with the past in the chronological, spatial, and discursive outlines of [the] Palestine[sic] struggle”1 with many internalizing Israel’s systems of hierarchy and fragmentation and structures of violence. Active remembering, then, can be seen as a critical exercise that offers a vigilant stance against the tyrannical state and does not lose sight of the historical conditions of Israeli policies that have culminated in genocide and scholasticide in Gaza and continue to attack the educational institutions in the West Bank.

2.

From an article titled “The Stone and the Pen: Palestinian Education During the 1987 intifada” by Yamila Hussein in The Radical Teacher, Fall 2005, No. 74, Teaching in a Time of War, Part 2, pp. 17-22 and published by University of Illinois Press.

It is worth noting that following its occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, Israel took control over the educational sector. It did so in a fashion that Sarah Graham-Brown aptly describes as “schizophrenic” (qtd. in Hussein 17);2 i.e. curricula, certificates and national exams in schools in the West Bank would be administered by the Jordanian government and schools in Gaza by the Egyptian government. However,

Some of the Israeli practices between 1967 and 1987 (before the first intifada broke out) included raiding campuses, firing live bullets, arresting students and staff, routinely closing schools temporarily or permanently, and turning them into military bases. In addition, between 1986 and 1987, all Palestinian universities were subjected to closure by Israel over a varying period of time (Hussein 18). This constant assault on the Palestinian educational system has been a consistent policy, and in early 1988, it was manifested in a tyrannical decision to indefinitely close all educational institutions in the West Bank. Yamila Hussein explains how the military decree to close schools was declared:

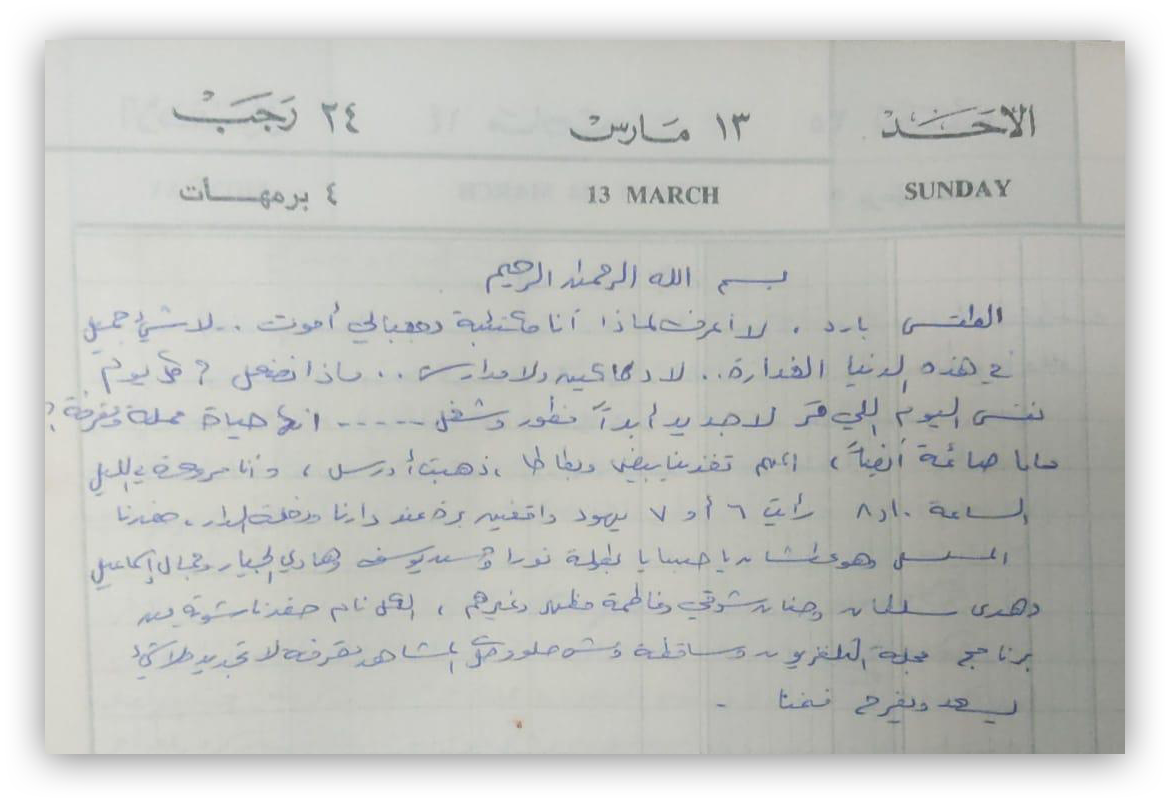

My mum, Deena, was one of the 300,000 school students who were affected by the closure. Mum has kept a diary since as early as 1988. Her entries are a mix of the political and the personal. My mum was attending high school when the military order was announced and school closed. She just finished the first semester of Al- Tawjihi which is the general secondary education certificate examination. She would repeatedly express her heartbreak as a result of the closure. After graduating high school, my mum could not join a university as the educational institutions were still routinely shut down. She would confide in her diary the devastating sense of disappointment as she was deprived of continuing her education because of Israel’s policies. With her permission, I am including snippets of her diary entries that might give the reader a sense of life during the first intifada for a young woman trying to make sense of the world around her. The account is personal but can also speak to a general state of having to deal with disruption and living in a heightened period in a long, protracted struggle for freedom.

Israel ran every aspect of government schools: maintenance, hiring, firing, salaries, budget, staff, students, school-year duration, and holidays. All schools had to follow the Jordanian or Egyptian Israeli-censored curriculum and all educational institutions were subject to military harassment. Israel deleted and banned references to Palestinian culture and history, or any idea that contradicted Israel’s political agenda. Over thirty-five school textbooks were banned between 1967 and 1987. Teachers and students were denied their right to organize on a professional basis and unions were outlawed. (Hussein 18)

Some of the Israeli practices between 1967 and 1987 (before the first intifada broke out) included raiding campuses, firing live bullets, arresting students and staff, routinely closing schools temporarily or permanently, and turning them into military bases. In addition, between 1986 and 1987, all Palestinian universities were subjected to closure by Israel over a varying period of time (Hussein 18). This constant assault on the Palestinian educational system has been a consistent policy, and in early 1988, it was manifested in a tyrannical decision to indefinitely close all educational institutions in the West Bank. Yamila Hussein explains how the military decree to close schools was declared:

Closure orders usually with no mention of when schools would reopen were orally issued to individual school administrators, announced on TV and radio and disseminated in written memos such as this one:

Greetings,

The Schools of this district will close until further notice as of the morning of Thursday, 4 February, 1988.

This decree was signed "with respect" by the Israeli Director of Education, who functioned under the Israeli ministry of defense. It denied over 300,000 school-age West Bank Palestinian students access to their nearly 1,200 schools.

My mum, Deena, was one of the 300,000 school students who were affected by the closure. Mum has kept a diary since as early as 1988. Her entries are a mix of the political and the personal. My mum was attending high school when the military order was announced and school closed. She just finished the first semester of Al- Tawjihi which is the general secondary education certificate examination. She would repeatedly express her heartbreak as a result of the closure. After graduating high school, my mum could not join a university as the educational institutions were still routinely shut down. She would confide in her diary the devastating sense of disappointment as she was deprived of continuing her education because of Israel’s policies. With her permission, I am including snippets of her diary entries that might give the reader a sense of life during the first intifada for a young woman trying to make sense of the world around her. The account is personal but can also speak to a general state of having to deal with disruption and living in a heightened period in a long, protracted struggle for freedom.

My mum at her desk – February 1988

My mum here writes:

She then moves to numerate the goods that her dad brought to the house and the social activities that she took part in, including the meal she and her sister prepared and ate. My mum took her studies seriously even when the schools were closed. Here she writes all the subjects she was revising for, including religion, science, and history. She also notes down what she watches on TV and what she thinks of it. For this entry, she writes,

Mum then signs the entry as if it was an official document.

I wish that March will be a month full of goodness and happiness, but where does happiness come from while we are under the bitter and ugly occupation and schools are closed with no available news as to when they will reopen? We only come to know one piece of news, and that is that the results of the first semester of high school will be announced the day after tomorrow…

She then moves to numerate the goods that her dad brought to the house and the social activities that she took part in, including the meal she and her sister prepared and ate. My mum took her studies seriously even when the schools were closed. Here she writes all the subjects she was revising for, including religion, science, and history. She also notes down what she watches on TV and what she thinks of it. For this entry, she writes,

After the news, we watched a documentary about the occupied territories in English and translated to Arabic. They showed scenes from Jerusalem and Hebron and aired people’s views. The programme is good. Then we watched a series from the TV archives.

Mum then signs the entry as if it was an official document.

This is the entry of March 03:

When asked why she keeps a journalistic and passive voice when writing about the news throughout her diary, mum said that she always wanted to be a journalist. She would spend hours reading daily newspapers, including Al-Quds, noticing and imitating the distant style of reporting.

Tear gas seeps to Ramallah hospital in dispersing a protest / an arrest spree in Ein ‘Arik [a village west of Ramallah] / throwing five Molotov cocktails at military jeeps. The grades [of Al-Tawjihi] were supposed to be announced today, but unfortunately, they were not, and I am waiting to see what I have scored. I washed the dishes and Lolo [her sister] tidied up the place… I went to study though, swear to God, I do not know when we are going [back] to school to learn. It seems there will be no school, or we might redo the academic semester- God forbid!...

When asked why she keeps a journalistic and passive voice when writing about the news throughout her diary, mum said that she always wanted to be a journalist. She would spend hours reading daily newspapers, including Al-Quds, noticing and imitating the distant style of reporting.

3. Mum writes “Jews” in Arabic, and this is the usual way of referring to Zionists. She does not mean people practicing Judaism but rather Israeli soldiers; hence, my translation.

On her 13 of March diary entry, she writes:

Restrictions on movement coupled with closure of shops and schools left people with little to do and are mainly expected to remain indoors with little prospect. The sense of frustration and despair is described in mum’s words as she resorted to sleep in the face of a stifling routine.

The weather is cold. I do not know why I am depressed and wish to die. There is nothing beautiful in this treacherous life - No shops and no schools. What should we do? Every day is the same, nothing new at all. It is a disgusting and boring life?…On my way back home at 8:10 pm, I saw 6 or 7 Israeli soldiers3 outside our house. I entered the house and watched TV… There is nothing that brings us happiness, so we went to sleep.

Restrictions on movement coupled with closure of shops and schools left people with little to do and are mainly expected to remain indoors with little prospect. The sense of frustration and despair is described in mum’s words as she resorted to sleep in the face of a stifling routine.

In recapping the month of March, she notes down:

Considering mum’s remarks whilst thinking of the starvation Israel is currently manufacturing in Gaza, one should note that a cruelly imposed state of scarcity has always been one of the strategies Israel adopts as collective punishment.

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful

Our Life in a Few LinesWhat should I say? These months that just passed have all been bitter and not sweet at all, for a number of reasons, most importantly of which, is the deadly and ugly intifada in addition to the closure of schools and universities, as schools were shut down in February and March while universities in January, February and March, and I do not know what will happen in April. That, in addition to the fact that Israel threatens the livelihoods of people in the occupied territories. We now are in need of food and groceries, but Allah is the most sufficient and capable of everything. As for papa, he goes out every day to search for food and all that we need…

Considering mum’s remarks whilst thinking of the starvation Israel is currently manufacturing in Gaza, one should note that a cruelly imposed state of scarcity has always been one of the strategies Israel adopts as collective punishment.

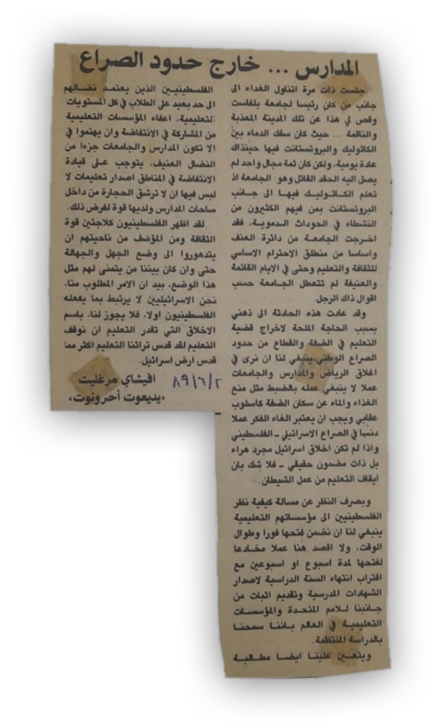

Al-Quds newspaper Clipping, 02 June 1989

In trying to understand what kind of conversations were being held amongst Israeli circles, my mum clipped a translated piece published in the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth and written by Avishai Margalit titled “Schools…Outside the Conflict” that appeared in Al-Quds newspaper on 02 June 1989. Margalit starts his argument by narrating an anecdote and establishing analogies between the Protestants and Catholics in Belfast, North of Ireland and Palestinians and Israelis. Margalit points out that “whilst bloodshed between Catholics and Protestants was then a daily occurrence, there was one aspect that murderous revenge did not touch which was the university as the Catholics learned alongside the Protestants including participants in bloody incidents.” He continues to say, “I recall this conversation because of the dire need to leave education in the West Bank and Gaza outside the national struggle. We need to see closure of kindergartens, schools and universities as something we should not do just like depriving the inhabitants of the West Bank from food and water as a punitive measure. Ignorization is a profane act in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and if Israel’s morals are not nonsense but are true in essence, then stopping education is undoubtedly Satan’s work.” He then argues for an immediate reopening of educational institutions in a way that is not only done in “a sneaky manner for a week or two at the end of the academic year just to produce certificates and show proof from our side to the United Nations and educational institutions around the world that we are allowing regular education.” Indeed, the Israeli military opened the schools in May 1988 but only for two months before closing them again. This was done because Israel had concerns that, in the wake of the closure, Palestinians were creating their own educational systems, and it had no control over the process (Hussein 19).

Indeed, and in the aftermath of the military order closure, there was an organically immediate and spontaneous response by the Palestinian community to create alternative education initiatives and for the first time, Palestinians did have a space, albeit fleeting, limited and fraught, to decide what and with whom and where they or their children can learn. Grassroots education, in the form of Popular Teaching projects amongst other shapes, was an opportunity to move away from Israeli-censored Jordanian curriculum and to build one that is more attuned to the Palestinian culture and the students’ lived experience. Since there was no pre-set curriculum to use, educators had the opportunity to be creative with the teaching material, including leaflets, newspapers and Palestinian songs and poems. Naturally, “Popular Teaching was in touch with the realities of the children and teachers, their fears, dreams, needs and resources” (Hussein 19). Organised by community members, education took place in private homes, mosques, churches, public spaces, educational centres and even outdoors and under trees. The latter is more convenient “for an easier and safer dispersal of the ‘class’ in case the soldiers invaded” as the “Israeli military forces considered all forms of organized learning a violation of the school closures they imposed, and they declared all forms of organized popular activities illegal” (Hussein 20). Indeed, this defying act of resistance has been viewed as “civil disobedience” (Hussein 20).

Commenting on the teaching/learning experience during the intifada, Professor Roger Heacock remarks,

4. This is part of an intervention in a series titled Radical Fridays organised by the Institute of Palestine Studies. Professor Roger Heacock’s remarks here are in part II of a conversation about the first intifada under the title of The Radical University and was convened via Zoom on 11 June 2021. The full conversation can be found here.

We all realized that the activism of previous months and years had had a purpose as a rehearsal, as a preparation for a protracted struggle that had to end, we thought, with Palestinian self-determination. Students were teaching professors, professors were teaching students, all were teaching each other by acting out the literature that they were reading to themselves and each other. And here I’m speaking of teaching as تربية and not as simple تعليم since their whole being, not just their mind and their memory were involved.4

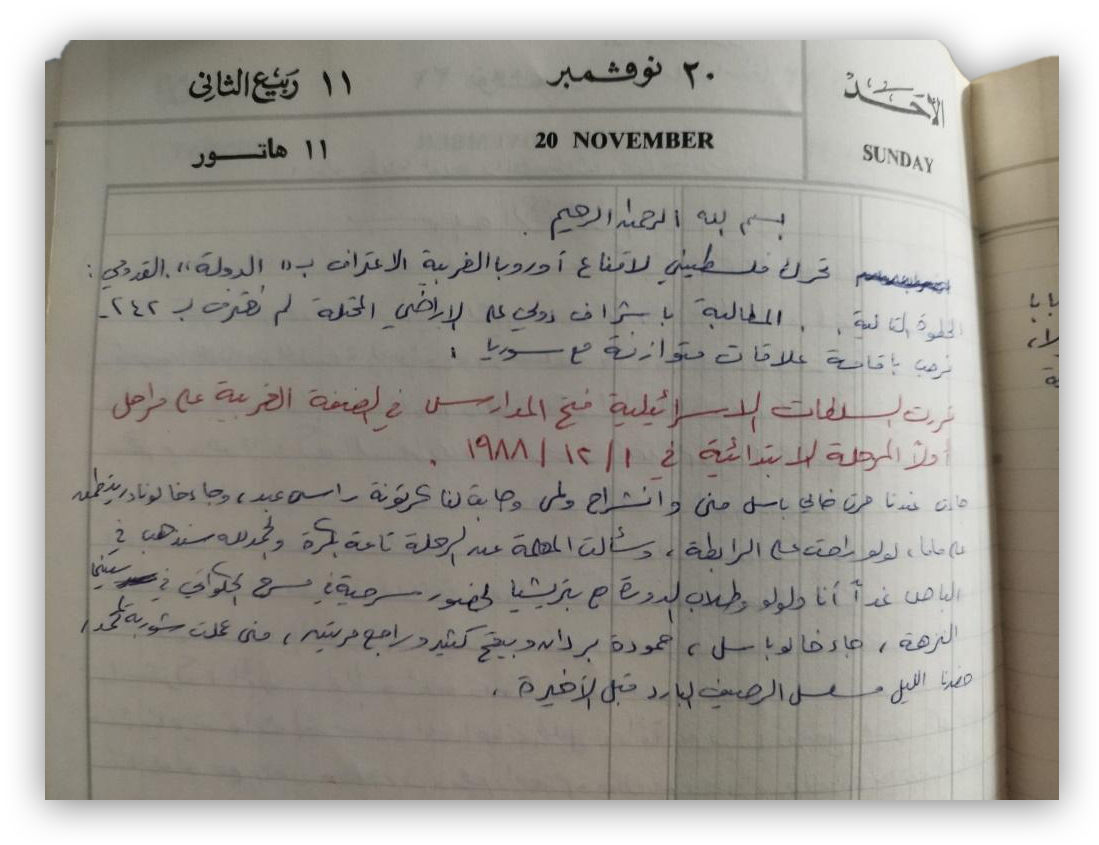

Mum’s diary entry of 20 November 1988 reads:

Here, mum’s lived experience illuminates two important points: first, my mum and her peers could go to Jeursalem to see a play. Even during the first intifada, people could still move from the sea to the sea (from the Dead Sea to the Mediterranean). That would change in the wake of the Oslo Accords. Secondly, the important role of educational centres, like the ones mum mentioned: Yasser Educational Centre, the Young Women Centre and charitable associations like the University Graduates Union is highlighted in providing alternative education and places for the students and teachers to meet and continue the learning process. Mum keeps referring to them in her diary and considers them as a refuge and a space to contunie learning. Unfortunately, these centres were “seen mainly as a stopgap measure to fall back on until schools were reopened and instruction went ‘back to normal’. However, ‘normal’ had become an Israeli policy of arbitary opening and closing of scools” (Hussein 20). This sense of disorientation compounded by Israel’s “threats of prison [up to 10 years!], large fines, and expulsion were serious enough to frustrate these decentralized and unprotected initiatives” especially those conducted by Popular Committees. The latter are comprised of volunteers sustaining the intifada and responding to community needs including in the educational sector. These committes were banned by Israel in August 1988 and hunderdes of the memebers were arrested or sent into exile (Hussein 22,20). Israel’s continuous assualt on the organic educational initiatives meant that they could not be sustained. Thus, the decision for the schools to reopen was waited for by many, including my mum who is using a different pen to highlight the importance of the information.

Palestinian mobilisation to convice Western Europe to recognise the ‘state of Palestine’. [Faruq] al-Qaddumi [the then Secretary-General of Fatah]: The next step is to ask for an international oversight in the occupied terriroties. We have not recognized 242 [the UN resolution that calls for the withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the 1967 war] and we welcome having a balanced relationship with Syria.

Israeli authorities have decided to [re]open schools in the West Bank in awaves, starting with the intial phase on 01/12/1988…

Lolo [her sister] went to the University Graduates Union and asked the teacher about tomorrow’s trip, and thank God we will take a bus tomorrow - myself, Lolo, and the students of the course with Patricia to see a play in El Hakwati [the Palestinian National Theatre] in Al-Nuzha Cinema…

Here, mum’s lived experience illuminates two important points: first, my mum and her peers could go to Jeursalem to see a play. Even during the first intifada, people could still move from the sea to the sea (from the Dead Sea to the Mediterranean). That would change in the wake of the Oslo Accords. Secondly, the important role of educational centres, like the ones mum mentioned: Yasser Educational Centre, the Young Women Centre and charitable associations like the University Graduates Union is highlighted in providing alternative education and places for the students and teachers to meet and continue the learning process. Mum keeps referring to them in her diary and considers them as a refuge and a space to contunie learning. Unfortunately, these centres were “seen mainly as a stopgap measure to fall back on until schools were reopened and instruction went ‘back to normal’. However, ‘normal’ had become an Israeli policy of arbitary opening and closing of scools” (Hussein 20). This sense of disorientation compounded by Israel’s “threats of prison [up to 10 years!], large fines, and expulsion were serious enough to frustrate these decentralized and unprotected initiatives” especially those conducted by Popular Committees. The latter are comprised of volunteers sustaining the intifada and responding to community needs including in the educational sector. These committes were banned by Israel in August 1988 and hunderdes of the memebers were arrested or sent into exile (Hussein 22,20). Israel’s continuous assualt on the organic educational initiatives meant that they could not be sustained. Thus, the decision for the schools to reopen was waited for by many, including my mum who is using a different pen to highlight the importance of the information.

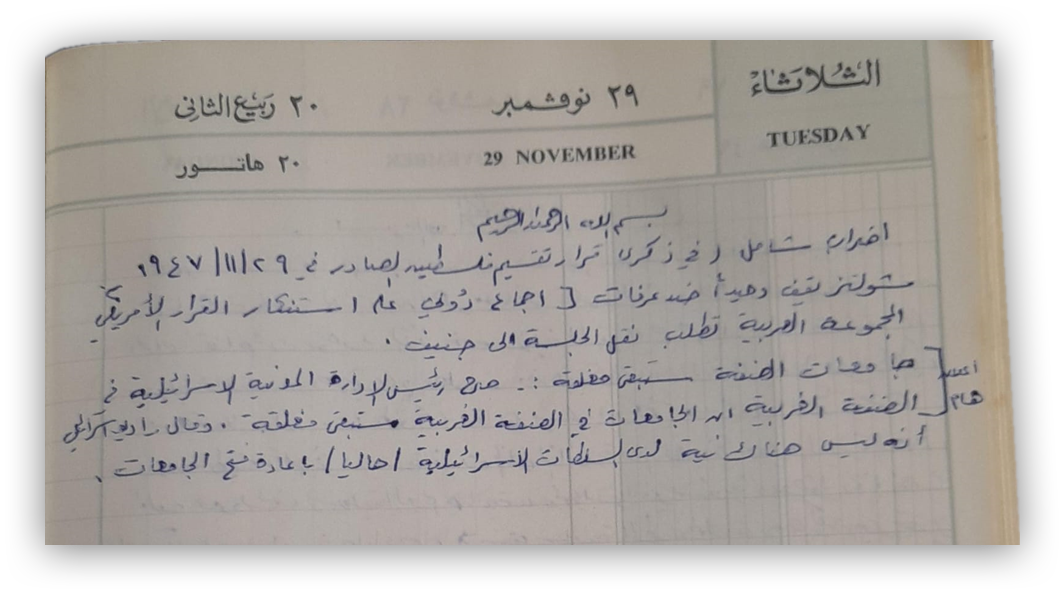

The 29 November entry reads:

Here the entry shows that whilst the schools were announced to reopen in stages, the Israeli authorities decided to keep universities closed.

General strike in commemorating the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine adopted on 29 November 1947.

[George] Sholtz standing alone against Arafat: General international consensus to condemn the American decision [The United States refused to grant the head of the Palestine Liberation Organization and his accompanying delegation entry visas to participate in the United Nations General Assembly in New York] and the Arab league demand the session to be held in Geneva.

Important announcement: The universities in the West Bank shall remain closed: The head of the Israeli civil administration in the West Bank declared that universities in the West Bank will remain shut. The Israeli radio said there was no intention on the part of Israeli authorities, currently, to reopen universities.

Here the entry shows that whilst the schools were announced to reopen in stages, the Israeli authorities decided to keep universities closed.

The main headline reads:

Druze Israeli soldiers break into our house and twist our mother’s arm.

Mum ends the year of 1988 with that entry that conveys a lot. She notes down her attempts to learn skills like computer and sewing whilst waiting for the Israeli military to allow the universities to open. The volatile atmosphere seen in the common blackouts of electricity and military break-ins are stated. With the constant restrictions on movement and curfews, there were no evening classes provided to students. The violence with which Israeli soldiers break into houses and terrorize families was and still is a usual practice. My grandfather’s visit to the Civil Administration office shows his attempt, however futile, at protesting the terror of the state.

Druze Israeli soldiers break into our house and twist our mother’s arm.

I went to the University Graduates Union to ask about the Polytechnic University as I might continue my education there if universities [re]open. I entered the second floor and headed to the registration room. For the literary stream, only arts, pottery and architecture are open. I asked for afternoon hours, but the officer told me there was no evening shift. The working hours are only from 8 am to 3 pm…

I left, went home and prayed, and we had a washing day, then at 12 pm, I went to the Young Women Centre and thank God, the electricity is on today. I then came back home and brought Lolo’s dress and drew a winter dress patron. I then went to Yasser Cultural Centre at 2:20 and we took the basics in computer and everything we took earlier was an introduction. I went home at 4:30 pm and to my surprise I saw my grandmother… [and other relatives]. Lolo narrated what had happened which is: Our mum was hanging the laundry, when an impolite Druze soldier stood in front of her and told her to come over. Mum refused, went inside and locked the door. Infuriated, the soldier with another English and Hebrew-speaking soldier broke the door. The locker got twisted and the glass window of mum’s room got shattered and the knob of the door broke. The soldiers entered the house and took mum outside and twisted her arm. Mum hit him with her boots. The soldier demanded to know who was throwing stones. Mum started cursing him and calling on dad. Neighbors became alerted… and tried to get closer but the Druze soldier threatened them. He wanted to take mum to the [military] jeep. Dr. Yusuf Al-Shaarwai showed up and told the soldier that mum had boys and girls. All while the second soldier was pointing the rifle towards Lolo, Duaa’, Asmaa’ [her sisters] and the boys [her brothers] – all crying and screaming. Lolo spoke to the soldier in English and said: “This is the last time”. They left. Fawzi Hijazi came and fixed the door and neighbours came to congratulate mum on her safety…then papa came home and was filled in and went with Fawzi and Uncle Nader to the Civil Administration office to complain about today’s incident.

Mum ends the year of 1988 with that entry that conveys a lot. She notes down her attempts to learn skills like computer and sewing whilst waiting for the Israeli military to allow the universities to open. The volatile atmosphere seen in the common blackouts of electricity and military break-ins are stated. With the constant restrictions on movement and curfews, there were no evening classes provided to students. The violence with which Israeli soldiers break into houses and terrorize families was and still is a usual practice. My grandfather’s visit to the Civil Administration office shows his attempt, however futile, at protesting the terror of the state.

Whilst translating mum’s diary, I kept thinking of Asma Mustafa, who is an English teacher from Gaza who shares her powerful and heart-wrenching account as an educator on the run via Manhajiyat. Reading them side by side has reaffirmed my understanding that the scholasticide in Gaza is not recent aberration but rather a continuation of a long-standing Israeli policy to destroy the Palestinian educational infrastructure and system.

5.

Meir Litvak in Collective Memory and the Palestinian Experience published by Palgrave MacMillan 2009.

The punitive measures of Israel towards the Palestinian people that have dared to demand freedom have always been the go-to response to any revolutionary practice. The daily implications of such measures are partly expressed in a personal account, my mum’s diary. Amidst the fragmentation of the Palestinian people, shards of the memory, including personal diaries, like my mum’s or digital accounts like that of Asma Mustafa’s, are important archival documents and are a testimony to the entanglement of the personal and the political. The juxtaposition of the overwhelming, like being in the crosshairs of the rifle, and the mundane, like watching TV, shows the surreal nature of living under the Israeli occupation. Mum’s subjective experience of the national events shaping what would be known as the first intifada is a testimony that nationalism is constituted by a “multiplicity of conflicting memories”.5 A thread that appears across the entries is Mum’s attempts to read the uncertain as she waits for the school to reopen. She usually starts the entries with the political news as headlines and then moves to the mundane, everyday activities. Throughout it all, she has this reporter’s voice with little commentary and so much frustration.

A picture found in the diary that shows mum’s father and her two younger sisters in their school uniform/date unknown