Mahvish Ahmad

On Political Friendship and Archival Labour:

Working with a Radical

Library in Pakistan

Behind

a 40,000-strong collection of Pakistan’s socialist and democratic movements -

collected by the Punjabi poet, Urdu journalist, and progressive political

worker, Ahmad Salim - are invisible acts of love and labour that shelter and

nurture a wandering archive and its archivist. To

work with Salim and his archive is an act of political friendship; to sustain it for scholars and organisers of the left, a profoundly

undervalued, laborious,

and necessary undertaking.

[1]

At the time, my intention was to

write a PhD about the National Awami Party, a left political formation that in

the 1950s brought together urban communists and ‘minor’ nations in Pakistan,

for the purposes of establishing a socialist multinationalism state. Ahmad Salim

was a member and political worker with NAP.

I

first met Ahmad Salim in the living room of Dr Humaira Ishfaq, a scholar and

professor of Urdu literature in Islamabad, who in a moment of big-hearted

kindness convinced her husband that they should move this poetic soul of an

archivist, this former political worker of the left, into their home. I had

heard from fellow scholars of the left, and socialist organiser-comrades, that

Ahmad Salim was the man to go to for documents on Pakistan’s socialist and

democratic movements. When I walked in, he was seated next to Dr Humaira’s children,

who had by this point adopted him as their nana, their maternal grandfather. My

first two hours were spent listening to a mix of Salim chastising his adopted

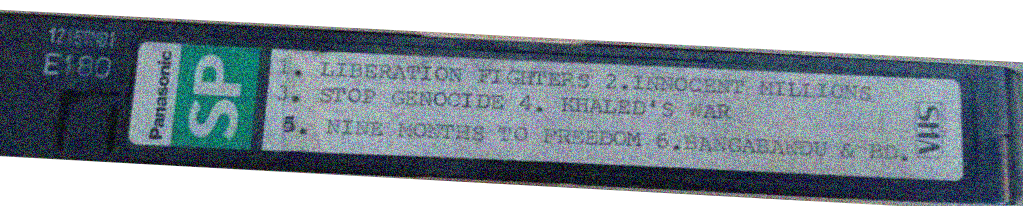

grandchildren and interrogating me, this new student of the Pakistani left. When convinced that my intentions[1] were acceptable to him, he led me to his

vast collection: piles of papers, books, cassettes, video tapes, and other

items collected from progressive friends up and down the country. When

he moved into Dr Humaira’s home, I realised, he brought not just the body of an

old man who needed care but a collection 40,000-strong that needed a home.

[2]

The project

was mostly funded

by a small Planning Grant from the Modern Endangered Archives Program run out

of UCLA. You can read

about it on their website here: https://meap.library.ucla.edu/projects/conserving-the-archives-of-progressive-pakistan/. Despite the grant and the

project, much remains to be done, and all those interested in supporting the

library are welcome to get in touch with me or the library via

www.sarrc.org.pk.

I was asked to pen a short

piece because of my work with Salim’s collection: I spent nearly two years working with him and a team of

librarians, archivists, digital designers, and scholars like Dr Humaira to

digitally index, physically sort, and make searchable his 40,000 items.[2] This piece should function as a resource for

others who might be interested in working with this kind of a collection; a

guide for those trying process what it means to collaborate with archives and

their archivists. I opened with how Dr Humaira gave Salim and his archive a

home, because for me it represents the two most important ingredients in any

such collaboration: love and labour. When Dr Humaira met Salim, she told her

husband that she could not help but feel a deep affection for this old man, his

pen and his political commitments.

[3] Ahmad Salim has recently published his

autobiography, Meri Dharti, Mere Loag (Sang-e-Meel 2022). Dr Humaira

comments on his autobiography at the 2023 Pakistan Literature Festival in

Lahore, using the opportunity to launch a critique of the exclusions manifested

at the festival itself, as well as mainstream ideas of what constitutes Urdu

literature and the history of the land. The book launch panel, in which Dr

Humaira launches this intervention, can be listened to here

For

Dr Humaira, Ahmad Salim was a teacher whose capacious writings as an Urdu

historian and Punjabi poet had undone her. He was also an archive in his own

right, born just two years before Partition in 1945, a repository of a

capacious life that itself is a tale of erased and marginalised histories.[3] A few years after moving

him into their home, when Salim fell extremely ill and had to undergo surgery,

Dr Humaira and her husband Qaiser showed up at the hospital with the deed to a

parcel of land 45 minutes outside of Islamabad. “We’re going to build you the

library you always dreamed of,” they told him. They spent the next few years

funding and managing the construction of the three-story building, which today

houses Salim’s entire collection. They mirror Salim’s own love for progressive

politics and art, which he has both been part of creating and collecting over

decades. And, they follow (and make way for) a long line of political

friendships, kinships, comradeships, that have sustained this poet, writer, and

archivist and his vast archive through relentless and committed, invisible, and

crucial labour.

In

the rest of this contribution, I’ll speak a bit more about Salim’s

archive: How it came about, what wonders it contains, and why I started to work

with it as one contribution to a broader, networked, and historical effort to

build left infrastructures in Pakistan. And, I’ll return to the themes of

political friendship and archival labour, relations and processes that

privilege the collective reproduction of life and politics. Despite their absolute

centrality in the making and maintenance of left archives under conditions of

repression and neglect, both comradeship and care is often invisibilised.

Collaborating with a progressive archive – and the broader politics of which it

is a part – requires a willingness to enter those marginal but invisible,

collective networks of relations and work that have always been central to the

making of the left.

[4] He penned

critical essays and poetry condemning the centralisation of power, writing against

the 1971 atrocities of the Pakistani military in what is now Bangladesh, and in

favour of Pashtun, Baloch, Sindhi, and other marginalised national demands to

decentralise political and economic power.

A Progressive Archive and its Archivist

About forty years ago, Ahmad Salim declared himself chronicler of all things progressive. When he started, he was already enmeshed in networks of political and cultural workers trying to build a left to be reckoned with; his archival work was an extension of this. He was a member of the National Awami Party, a pan-peripheral alliance of marginalised nations and urban communists; he was a member out of the country’s most powerful province of Punjab.[4] And, he was a Punjabi poet who joined the famous communist Urdu literary giant, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, when the latter established the Pakistan National Council of the Arts in 1973, to help archive “lok adab” (people’s or folk literature) and set up Lok Virsa, the National Institute of Folk and Traditional Heritage, under the Pakistan People’s Party government. Around this time, a visiting research student he helped to gain access to some documents, thanked him for access to his “archive.” Then it dawned on him: He should build one, to house those items state institutions would find too incendiary to record. When Zia ul Haq, the second military ruler, took over at the end of the 1970s the necessity of this work became all that more important. Part of the global alliance against communism in the final decade of the Cold War, tasked to train mujahideen in their fight against the Kabul government and the Soviet invasion, Zia turned his ire onto a rich network of leftists within Pakistani borders. He effectively hanged Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in a trumped up murder charge, drove Faiz into exile in Beirut, and hounded and arrested Salim and his comrades. Salim knew that critical and pro-democracy documents produced for instance by the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy against Zia, would never find a home in the National Library or the National Documentation Centre—at least not beyond their representation in radio surveillance briefs and police reports. So, he delegated himself a simple task: Collect everything under the sun. Hoard every chitti (letter), poster, pamphlet, magazine, notebook, audio recording, VHS tape, CD, book, encyclopedia. Record interviews with striking union workers and fishermen and never throw them away. Get to know as many poets and writers, actresses and drama stars, producers, and scriptwriters as humanly possible (Pakistan’s cultural scene was long dominated by the politically progressive, despite the state of its formal politics, and during Zia’s regime Salim took refuge in showbiz journalism to avoid further arrests). Scour the country for ageing leftists and their descendants, to ask them whether they have anything left at all, any diaries or personal letters, scribbles and photos, that he can come to pick up and store away.

[5] At a recent

panel at the 2023 Pakistan Literature Festival, launching Ahmad Salim’s Mere

Dharti, Mere Loag (Sang-e-Meel 2022), Dr Syed Ahmed Jaffer recounted a telling story of

Salim’s struggles. Many years ago, Salim submitted poetry won a collection of

Faiz’s entire collection of poetry, after submitting his own work to a

magazine. The collection had been donated as a prize gift by Faiz himself.

After three days, Faiz found the collection being sold at a street corner and

approached Salim to ask him why he got rid of Faiz’s entire literary collection

for money. Salim answered: “Faiz Sahib, after the third day, my stomach could

no longer bear the faqa, the fast, the starvation.”

The

South Asian Research and Resource Centre, the innocuous name that Ahmad Salim gave to his ambitious endeavor, is the product of forty years of stockpiling

histories of the left, so that those who survive him, and his friends can learn

about histories neglected and erased by a constellation of military rulers,

political elites, big business, and land barons that, at the very best, tell a

story of the country’s

leftists as one of lunatics and traitors. Behind it and Ahmad Salim’s vast

collection of writings and organizing is a story of a

wildly all-consuming dedication to his politics, his pen, and his archive, which

more than once drove him to the edge of hunger and homelessness.[5]

I decided to work with Salim in the summer of 2019, when I visited him on the first floor basement of the building that Dr Humaira and Qaiser had constructed for him.

I decided to work with Salim in the summer of 2019, when I visited him on the first floor basement of the building that Dr Humaira and Qaiser had constructed for him.

I

decided to work with Salim in the summer of 2019, when I visited him on the

first floor basement of the building that Dr Humaira and Qaiser had constructed

for him.

There, forty years of documents sat in piles around makeshift shelves that he

had been wanting to replace. A crumbled up,

partially ripped poster in one corner showed a setting red sun

next to Ho Chi Minh, printed by the United Workers’ Assembly of Lahore. In large, red letters it declared:

ڈوب رہا ہے سامراج ایسیا کے خون میں

Empire drowns in the blood of Asia!

Empire drowns in the blood of Asia!

[6] See Sara Kazmi’s work on the

Mazdoor Kissan Party, especially her article, The Hamlets

Hum in Punjabi,

written for Tanqeed, and her digital

Teaching Tool on MKP Circular, a pamphlet in the SARRC collection, for Revolutionary

Papers.

In

the room where Salim himself slept, amidst many of his papers, a small booklet

for Palestine, penned by a Muhammad Riaz Shahid, declared its solidarity in

Punjabi poetry. Under another pile,

the Sindhi Baloch Pushtoon Front outlined a confederal constitution, one of

many alternative visions for how to constitute a Pakistan more inclusive and

capacious of its marginalised nations.

And those were just the ones that stood out to me, invested as I was in

revisiting left internationalism and alternative, multinational imaginations of

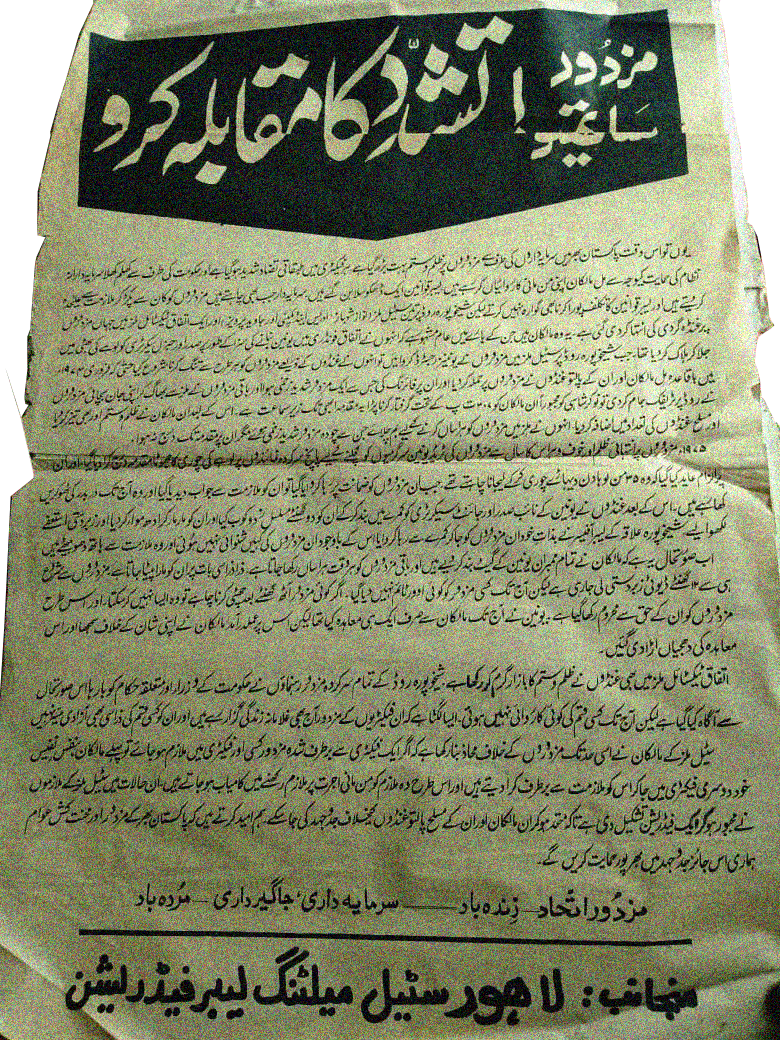

postcolonial collectivity. There was his prized collection on Punjabi history,

literature, music, art, theatre, and politics. Sara Kazmi and Hashim bin

Rashid, two friends and comrades who had travelled with me to Salim’s library

that day, had been spending time digging up pamphlets and writings of rural

movements around Punjab. This included the papers of the Mazdoor Kissan Party,

or Worker’s Peasants Party, which among other things tried to imagine a

people’s literature in Punjabi for the purposes of mobilising the masses.[6] His vast and rich, material collection was a reminder that at a time of archival turns, where our very idea of what constitutes

repositories of memories on the past has become so beautifully extensive,

old-school archives with their ageing papers still need our care

and attention.

[7] Mijke van der Drift’s work on

non-normative ethics and transfemme futures has been immensely generative for

me as I articulate my own arguments around the necessity for militant and

insurgent scholars engaged rather than disembedded from political movements.

Read more about Mijke’s work at https://goldsmiths.academia.edu/MijkevanderDrift.

During

this particular visit, I was working through what it means to stay engaged with

the Pakistani left from abroad. I was in Cape Town at the time, a postdoc at

the University of the Western Cape, but was on my way to London to start a new

job at LSE. Tensions between “diaspora” academics and left

organisers and scholars still in Pakistan had always run high, for all sorts of

reasons ranging from political differences to professional competition to the

fact that the immediate enemy looks different depending on where you stand

(e.g. Islamophobia in Europe, Sunni majoritarian Islamists in Pakistan).

Central to the disagreement has been differences around the correct

interpretation of the political terrain and the priorities of the left. The ongoing split between inside/outside Pakistan reflected for me a

deeper assumption around what it means to build and sustain left politics: that

individuated discourse trumps collective

work. A dear friend and comrade, Mijke van der Drift,

recently articulated this hunch back to me, when they said: “Some think truth

is action. But action is also truth.”[7] What they meant was that the speaking-truth-to-power move was all well and

good, necessary even, but that it is only by labouring together that we can

construct new truths, or new worlds.

Political Friendship, Archival Labour and the Building of Left Infrastructure

Over the next two years, Salim and I spent several hours on the phone together concocting various ways to find money that could fund the transformation of his collection into a functional library (this was pandemic time, and plans to travel back to Pakistan had been thwarted). Salim had a strict requirement, which I whole-heartedly agreed with: The documents must remain in Pakistan, accessible to scholars and organisers there, and the money should come with as little strings attached as possible. We identified the Modern Endangered Archives Project at UCLA, a donor interested in funding vulnerable 20th century collections in places like Pakistan, and went for their small (rather than large) grant because it allowed us to do exactly what we wanted: To hire a team of librarians and archivists who would generate metadata on the collection, transform that information into a searchable index, and relaunch a website with a search engine. SARRC’s collection could become searchable from anywhere in the world, but if someone wanted to access it they would have to make the effort to either contact Salim and ask him to send copies, or make the trek to the library itself.

Such things are not always admitted, but are perhaps necessary to reveal: To work with Salim and his archive required a commitment to staying in a friendship and comradeship with him and his collection—and a willingness to spend hours upon hours working on sometimes the most mundane tasks, like creating and checking excel sheets. Shahzad Abbas, the chief librarian, ran a team of archivists, coordinating all the work. Though none of us could circumvent working on the collection itself, it was Abbas and his team who made up the archival, library workers, who spent unending hours picking up 40,000 items and typing them into a list for us to check, re-check, and then check a third time. More than once, the team ran into its set of crises, mundane disagreements threatening to undo the massive task we had set ourselves. The largest, and perhaps most undervalued, exercise of our politics and ideological commitments was the willingness to stay in the work, together, come what may; a commitment to build a radical library that someone other than the 75-year old Salim could navigate (as Dr Humaira and Qaiser told me, more than once, they were completely unable to find anything in the collection, but mention it once to Salim and he’ll fish it out in a hurry).

Over the years, well-resourced libraries have offered to conserve Salim’s entire collection: To provide the money and the expertise they felt was necessary to preserve his items. The British Library had approached him more than once, he explained, but they wanted to take his collection and he wouldn’t have it. For a while he was salaried by the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam to transport left papers to Holland for safe-keeping. When he started bringing copies, instead of originals, wanting to keep primary documents in the country, he got into a disagreement with the IISH and the collaboration ended. A faculty member at a private university in Pakistan notorious both for several progressive faculty members and its hyper-securitised, gated campus, offered to transfer the entire collection to its library. This, however, would have made it inaccessible to all but the most privileged students and scholars, defeating the purpose Salim had set for himself, so he refused the offer.

In the end, the very making and sustenance of Salim’s archive has depended his, and others, willingness to enter into relations of friendship, kinship, and comradeship—to put in work and resources out of a commitment to preserve an autonomous, radical library in Pakistan. Dr Humaira and Qaiser have gone a step further, cultivating a kinship that goes beyond the solidarity inherent in political friendships. The many, many people over the years who have taken in Salim and his collection, paying for his surgeries and his shelves, donating their notebooks and inviting him to sift through their old boxes are, in turn, a model for a broader political friendship and archival labour. But perhaps foremost among us all us Salim Sahib himself, who committed his life to the memory of his friends and the new truths, and new worlds they have tried to build together.

Mahvish Ahmad works on the material legacies of anticolonial and Left movements, archival practices in sites of disappearance, fugitive organising under conditions of war, and the shifting techniques of imperial and sovereign violence, especially in Pakistan. She’s a UK-based Trustee of the South Asian Research and Resource Centre, the topic of this blog. She is also a co-founder of Revolutionary Papers, which studies anticolonial journals (with C. Morgenstern, K. Benson), Archives of the Disappeared, which investigates archive in sites of annihilation (with M. Qato, Y. Navaro, C. Morgenstern), and Tanqeed, an English-Urdu magazine of the Left in Pakistan (with M. Tahir). She’s an Assistant Professor of Human Rights and Politics at the London School of Economics.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎