Sara Kazmi

Protest poetry as archive:

From peasant struggles to immigrant internationalism

During the 1970s, a peasant movement emerged in Dera Saigol, a village about 30 kilometers from Lahore, Pakistan. Alongside political organizers from the Maoist Mazdoor Kissan (Workers and Peasants) Party, people in the village came together to reject the exploitative tenancy system, and claim the land for those who cultivated it. I travelled to Dera Saigol in May with Huma Safdar, Shafqat Hussain, and Muhammad Riaz as part of the Sangat, a progressive theatre and art collective that developed political education and performance based on vernacular and marginal literary traditions. We had been invited to sing, to share songs from 16th century rural rebellions and contemporary anthems by revolutionary poets. We parked our car by a field full of nodding stalks of yellow mustard, and walked over to the venue: a small courtyard inside a home, with a crowd of about forty sprawled casually on mats and day beds that were arranged in a circle. The gathering turned into an exchange, as the people of Dera Saigol also began to sing for us. In this intimate meeting, protest songs and poetry served to surface the collective memory of a political struggle.

Reflecting on the visit the next day, I was struck by the potential of poetry to serve as a movement archive: a repository of not just the issues and events that may shape a political movement, but also the stuff we do not always consider ‘archival’, i.e. the affective charge and collective memory that animate a struggle. In this essay, I draw on my engagement with activist performance in Pakistan to explore how poetry has powered imaginations of revolutionary internationalism in the global south. Through the Punjabi verses of working class poet Niranjan Singh Noor and anti-caste poet Lal Singh Dil, we can uncover an under-studied archive of non-canonical writing that interpreted Third Worldism and tricontinental solidarity through a distinctly local and vernacular poetics.

After we had performed a couple of songs, an older man, a musician and singer, offered to sing for us, “a song”, he explained, “written by our own movement in the 1970s”. My eyes widened with surprise as he began, and a familiar tune greeted my ears:

Reflecting on the visit the next day, I was struck by the potential of poetry to serve as a movement archive: a repository of not just the issues and events that may shape a political movement, but also the stuff we do not always consider ‘archival’, i.e. the affective charge and collective memory that animate a struggle. In this essay, I draw on my engagement with activist performance in Pakistan to explore how poetry has powered imaginations of revolutionary internationalism in the global south. Through the Punjabi verses of working class poet Niranjan Singh Noor and anti-caste poet Lal Singh Dil, we can uncover an under-studied archive of non-canonical writing that interpreted Third Worldism and tricontinental solidarity through a distinctly local and vernacular poetics.

After we had performed a couple of songs, an older man, a musician and singer, offered to sing for us, “a song”, he explained, “written by our own movement in the 1970s”. My eyes widened with surprise as he began, and a familiar tune greeted my ears:

Samina Hasan Syed sings “Naveyaan patraan de”. This 1970s recording was done by noted Marxist musicologist, Raza Kazim. Composition by Najm Hosain Syed.

Dera Saigol

Dera Saigol

He was singing a poem penned by Najm Hosain Syed, a Lahore-based Marxist Punjabi intellectual known for his translation of global Marxism into regional form and rural idiom. Syed’s poetry was central to Sangat’s plays and musical repertoire. He had been a close associate of the MKP during the 1970s, which is perhaps how the poem had made its way to Dera Saigol: many Lahore-based party workers were also regulars at the Sangat meeting that Syed hosted weekly at his home. I had read “Naweyaan Patraan De” (Of New Leaves) before at the same Sangat meeting, where it was passed around on an annotated sheet of paper, after which we all took turns to recite and analyze it. At Dera Saigol, the poem did not appear in its textual form, and it was not introduced as an individual poet’s work. Rather, it was marked as a “movement text”1, a song composed by peasants who fought to liberate their land - the grandparents and parents of those present at our intimate gathering. As the man sang, others joined in. I noted how the poem had been re-contextualized as a Dera Saigol anthem, and the individual poet’s author-ity stood diffused into a collective ownership of poetry as “the means of communal self-definition.”2 It had also been edited. The chorus, which repeats the refrain: “Naweyaan patraan de aao rung manaiye” (Come, let’s celebrate the colors that new leaves bring) had been modified such that the Punjabi word for “leaf”, patar, had been replaced with the Punjabi word for “son”, putar. The slippage revealed how Dera Saigol rewrote Syed’s poem to concretize its abstracted poetic gesture towards revolutionary transformation through a literal reference to the sons who have fought in the movement, and to those who are “new” to it, and will continue the fight.

1.

Ahmad, Mahvish. 2022. “Movement texts as anticolonial theory”, Sociology, 57(1), 54-71.

2. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. Decolonising the mind: the politics of language in African literature. Heinemann, 2005. First published 1986.

2. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. Decolonising the mind: the politics of language in African literature. Heinemann, 2005. First published 1986.

Often, poetry is referenced in scholarship and writing on political movements as a source of documentation, of key events and figures. However, Dera Saigol’s oral archiving of “Naweyaan Patraan De” points to a less obvious role played by poetry, some of which may not even be actually authored by movements, as in the case of Syed’s poem. Poetry can become a living, shifting container for the affect and atmosphere that shape a movement: for those continuing the Dera Saigol struggle in 2013, the poem archived sentiment, it archived joy, and made it available in a performative and collective form.

An anthology of Punjabi poetry published in Punjab, Pakistan during the 1970s.

An anthology of Punjabi poetry published in Punjab, Pakistan during the 1970s.Source: SARRC Archive, Islamabad, Pakistan.

This aspect of Punjabi poetry can be traced in the 1970s poetry produced by radical antiracist South Asian communities in Britain at the same time. During this period, Punjabis who left their own Dera Saigols to become immigrant workers that Britain needed to rebuild its war-ravaged economy were radicalized by their experience of racism and class exploitation. They went on to found the Indian Workers’ Association in 1958 which functioned as a trade union, community organization, and internationalist movement that synthesized Indian anticolonialism with global Marxism. The IWA also gave rise to a thriving literary and cultural sphere, with regular mushaira gatherings where poetry was sung and recited, and a proliferation of print forms that included poetry pamphlets and political magazines. A majority of this aesthetic production was in South Asian languages like Hindi, Punjabi, and Urdu, and remains under-explored as an archive of proletarian internationalisms in Britain and beyond. While the involvement of figures like British-Pakistani writer and activist Tariq Ali is well documented in histories of global left-wing solidarity with Vietnam, little attention has been paid to internationalist critiques of imperialism that circulated outside cosmopolitan spaces.

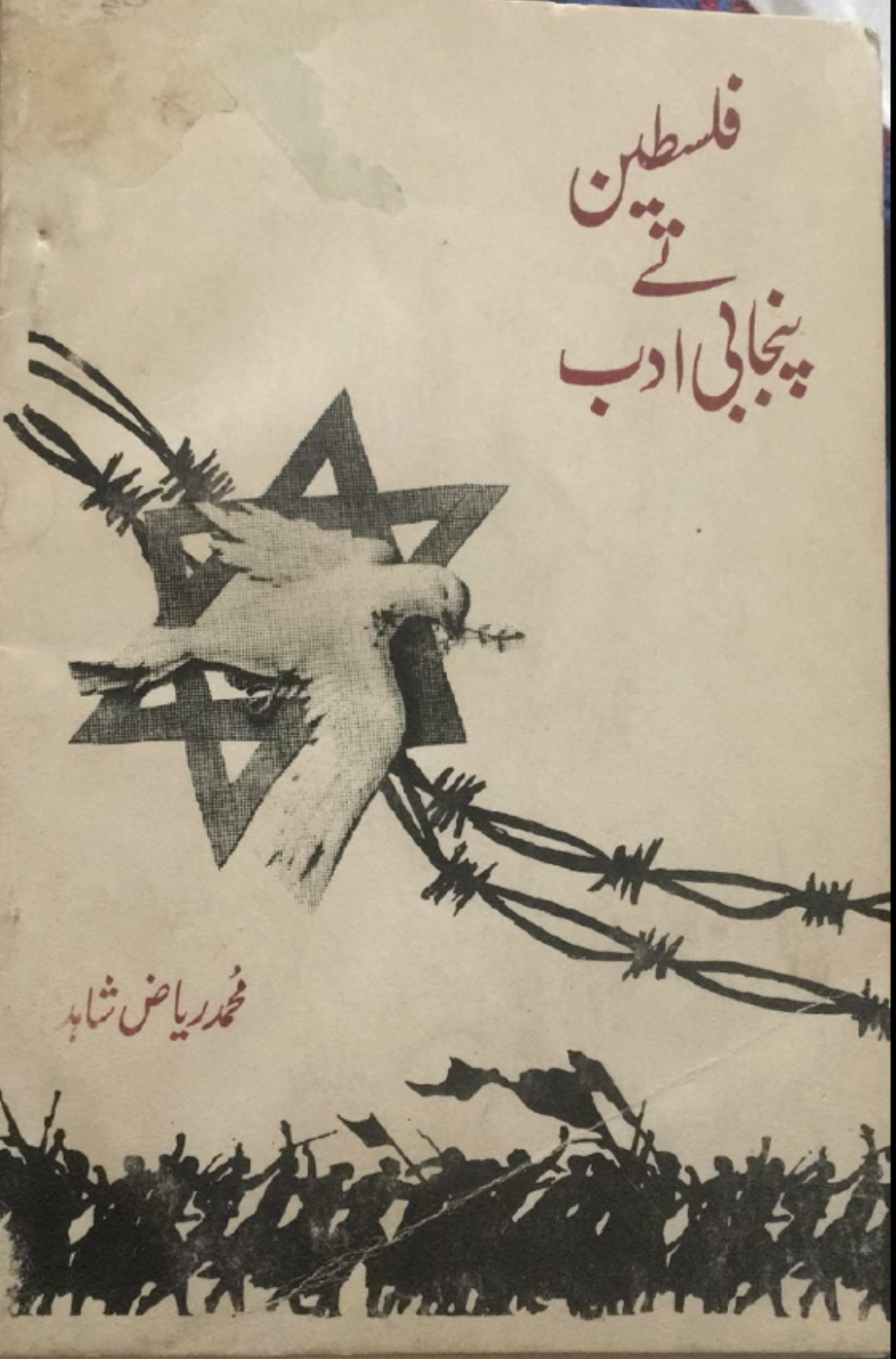

a 1975 cover of the Mazdoor Kissan Party Circular, the organ of the MKP. Alongside Ho Chi Minh’s photo, an inscription reads: “oin together the shining paths of Hashtnagar and Landhi. Bring back the memory of Ho Chi Minh!”

a 1975 cover of the Mazdoor Kissan Party Circular, the organ of the MKP. Alongside Ho Chi Minh’s photo, an inscription reads: “oin together the shining paths of Hashtnagar and Landhi. Bring back the memory of Ho Chi Minh!”Source: Noaman Ali

Poets like Niranjan Singh Noor, who had migrated to England from the heartlands of rural Punjab, echoed the poetic methodology I encountered in Dera Saigol and in Syed’s poetry. Noor wrote a book-length Punjabi ballad on the struggle in Vietnam, which was published alongside a 1970s Punjabi volume that contained several other poems and essays on Vietnam by immigrant workers in Britain. Noor’s “Ho Chi Minh” draws on storytelling traditions from the Punjabi literary tradition, pushing established conventions within socialist art by refiguring the relationship between local culture and internationalism. The ballad draws on hagiography, regional histories, and archetypes from the Punjabi literary tradition to conjoin India and Vietnam, spotlighting their oppression under and resistance against imperialism as the bedrock for forging a south-south anticolonial internationalism. This is accomplished through the poem’s treatment of time, and its construction of imaginative geographies that link the lives and the lands of the colonized:

Noor’s opening stanzas reference the physical features of the land: its rivers, flora and fauna, and fields, are paired with the symbols of the ‘amrit’ (sacred water, elixir) and the ‘talwar’ (sword). These symbols are invested with immense significance within Sikhism, and traditions of popular spirituality and histories of resistance. ‘Amrit' is water, a life-giving force, and the ‘sword’ the instrument of struggle symbolizing the long history of mass uprisings against both the Mughal empire and British colonialism (the flag of the Hindustan Ghadar Party for instance, bears two crossed swords). By mobilizing the affective power of these symbols, and alternating between images of the landscapes of Punjab and Vietnam, Noor creates an effect in which Punjab shades into Vietnam. Vietnam stretches to accommodate Punjab, metaphorized to narrate and archive local struggles from the poet’s context. While the poem’s narrative remains centred on Ho Chi Minh’s life, dates and years are not cited, and time is instead marked by referencing contiguous movements and liberation struggles. For example, he locates Ho Chi Minh’s adolescence in time by referencing the birth of the Indian National Congress, so that Ho comes to inhabit a kind of global, anticolonial time. Another reference links the Indian call for Swaraj (Home rule) to a turning point in Ho Chi Minh’s father’s life. Similarly, Noor likens the auditory ‘magic’ of Ho’s ‘lalkaar’ (call, challenge) to Bhagat Singh’s bombs, hurled inside the hall of the Legislative Assembly in New Delhi to “make the deaf hear”:

A similar move can be seen in Dalit Maoist poet Lal Singh Dil’s poem titled “Vietnam”:

Vietnam is like the hands of the east,

A life-giving elixir, I pay tribute to Vietnam!

Ni Tin

Punjab’s sword is Vietnam’s arm

The spirit is Vietnam’s, the youth is Vietnam’s

The sunflowers and roses are Vietnam’s

The Ganga is Vietnam’s, the Chenab is Vietnam’s…

( Noor 1989, 200) (My translation)

Noor’s opening stanzas reference the physical features of the land: its rivers, flora and fauna, and fields, are paired with the symbols of the ‘amrit’ (sacred water, elixir) and the ‘talwar’ (sword). These symbols are invested with immense significance within Sikhism, and traditions of popular spirituality and histories of resistance. ‘Amrit' is water, a life-giving force, and the ‘sword’ the instrument of struggle symbolizing the long history of mass uprisings against both the Mughal empire and British colonialism (the flag of the Hindustan Ghadar Party for instance, bears two crossed swords). By mobilizing the affective power of these symbols, and alternating between images of the landscapes of Punjab and Vietnam, Noor creates an effect in which Punjab shades into Vietnam. Vietnam stretches to accommodate Punjab, metaphorized to narrate and archive local struggles from the poet’s context. While the poem’s narrative remains centred on Ho Chi Minh’s life, dates and years are not cited, and time is instead marked by referencing contiguous movements and liberation struggles. For example, he locates Ho Chi Minh’s adolescence in time by referencing the birth of the Indian National Congress, so that Ho comes to inhabit a kind of global, anticolonial time. Another reference links the Indian call for Swaraj (Home rule) to a turning point in Ho Chi Minh’s father’s life. Similarly, Noor likens the auditory ‘magic’ of Ho’s ‘lalkaar’ (call, challenge) to Bhagat Singh’s bombs, hurled inside the hall of the Legislative Assembly in New Delhi to “make the deaf hear”:

Like Bhagat Singh’s bomb,

The magic of Ho’s roar,

Rent open the ears of the deaf

From inside the reeking jail cell,

The winds of truth declared war

(My translation)

A similar move can be seen in Dalit Maoist poet Lal Singh Dil’s poem titled “Vietnam”:

Even the old here

Can lob their wooden stick at a bomb,

Sending it flying back to the enemy’s camp,

Here, Gandhis do not enjoy the freedom

To enter the enemy’s camp to deliberate

The hanging of Bhagat Singh

(My translation)

A statue of Bhagat Singh and his comrades, Rajguru and Sukhdev, in Ferozepur, Punjab, India.

A statue of Bhagat Singh and his comrades, Rajguru and Sukhdev, in Ferozepur, Punjab, India. Source: Chris Moffat

Both poems about Vietnam reference Bhagat Singh, a 23-year old militant anticolonial revolutionary who was sentenced to death in 1931 for assassinating a British colonial officer. Singh was consecrated as a martyr in the popular Indian anticolonial imagination, and songs and poems celebrating his heroism became an entrenched genre within folk performance in Punjab:

Radhika Sood Nayak sings a “ghodi” honoring Bhagat Singh. The ghodi is a wedding song performed for bridegrooms. In this case, a ghodi sung for Bhagat Singh takes the shape of mourning, a song for a young life cut short by the colonial carceral state.

Shital Sathe and Kabir Kala Manch, a Dalit Marxist artist collective, perform an original song “Ae Bhagat Singh Tu Zinda Hai” (Bhagat Singh, You Are Alive) that connects their anticaste practice with Singh’s anticolonial legacy.

Yet, as Dil’s 1970s poem highlights through its wry juxtaposition of Gandhi’s rapport with the British, and Bhagat Singh’s absolute rejection of colonial authority, Singh represented an anticolonial legacy at odds with dominant Indian nationalism. Official and institutional histories of Indian anticolonialism center the Indian National Congress and its Nehruvian legacy, while other alternative and radical visions for decolonization like Bhagat Singh’s, find archival homes in the non-canonical space afforded by protest poetry, performance, and community memory. For Noor and Dil, postcolonial dissident poets against state-led authoritarianism in India, the comparative move linking Vietnam and India, Ho Chi Minh and Bhagat Singh, allows an internationalist poetics to double as an archive of anticolonial movements rendered marginal by the nation-state. Transmitted through song and oral circulation, in intimate community gatherings as in Dera Saigol, or in marginal sites of political education where movements face demobilization or state repression, poetry captures ground-up articulations of internationalism. Through its affective form, it embeds local and under-appreciated histories of struggle within global vocabularies of the Third World, allowing us to appreciate local histories of solidarity. By reading and listening to their poems today, we can access these under-represented archive stories, of how immigrant workers and marginal caste subjects imagined and articulated revolutionary internationalism.

Aao rung manaiye – come, let’s celebrate the color and vigor they bring.

Aao rung manaiye – come, let’s celebrate the color and vigor they bring.

A poetry recital, or mushaira, at an annual event commemorating MKP leader, ‘Major’ Ishaque Muhammad.

A poetry recital, or mushaira, at an annual event commemorating MKP leader, ‘Major’ Ishaque Muhammad.

Sara Kazmi

Sara Kazmi is a scholar, translator, and protest singer. From January 2024, she will be based the the Department of English at the University of Pennsylvania as Assistant Professor of Literature and Culture of the Global South.

Her research looks at poetry and drama from 1970s Punjab, in particular focusing on the re-working of oral, folk genres as a literary mode for subverting the bordering logics of the Indian and Pakistani state, and for critiquing the boundaries drawn by caste, patriarchy and institutional religion in the region. Sara has been involved extensively with the Sangat which is an independent group of artists, writers and musicians engaged in reading and revisiting the Punjab’s literary, musical and theatrical traditions. She is also a student of Indian classical music, blending ragas with folk tunes in her renditions of classical and contemporary Punjabi poetry.

Her academic work has appeared in the South Asia Multi-disciplinary Journal (SAMAJ), the Journal of Socialist Studies, and the South Asia Chronicle, while her literary criticism and long-form writing has been published by the Herald magazine, Dawn Books and Authors, The News on Sunday, and Poetry Birmingham.

︎ ︎

Sara Kazmi is a scholar, translator, and protest singer. From January 2024, she will be based the the Department of English at the University of Pennsylvania as Assistant Professor of Literature and Culture of the Global South.

Her research looks at poetry and drama from 1970s Punjab, in particular focusing on the re-working of oral, folk genres as a literary mode for subverting the bordering logics of the Indian and Pakistani state, and for critiquing the boundaries drawn by caste, patriarchy and institutional religion in the region. Sara has been involved extensively with the Sangat which is an independent group of artists, writers and musicians engaged in reading and revisiting the Punjab’s literary, musical and theatrical traditions. She is also a student of Indian classical music, blending ragas with folk tunes in her renditions of classical and contemporary Punjabi poetry.

Her academic work has appeared in the South Asia Multi-disciplinary Journal (SAMAJ), the Journal of Socialist Studies, and the South Asia Chronicle, while her literary criticism and long-form writing has been published by the Herald magazine, Dawn Books and Authors, The News on Sunday, and Poetry Birmingham.

︎ ︎