Jamil Fiorino-Habib

Reconfiguring the Archival Regime of Twitter in #Gaza Visual Narrative by a Cyborg

Just over 10 years ago on July 16, Israeli occupation forces killed four boys while they were playing on the beaches of Gaza. In what is now one of the most publicized atrocities of Israel’s deadly 2014 assault, a chilling image holds the last traces of these young lives, capturing the final moments leading up to their death.

![]() Figure 1: Three of the four Bakr boys killed on the beach, fleeing for their lives.

Figure 1: Three of the four Bakr boys killed on the beach, fleeing for their lives.

Source: Mondoweiss https://mondoweiss.net/2017/07/young-survivors-slaughter/

Figure 1: Three of the four Bakr boys killed on the beach, fleeing for their lives.

Figure 1: Three of the four Bakr boys killed on the beach, fleeing for their lives. Source: Mondoweiss https://mondoweiss.net/2017/07/young-survivors-slaughter/

1. For instance, in the Jewish-American newspaper, the Forward. https://forward.com/news/311710/one-year-later-the-bakrs-continue-to-mourn/

The photo has since become emblematic of the high civilian death toll and Israel’s intentional targeting of children, which we see even more intensely today, with the image sparking outrage across the globe from pro-Palestinian and even liberal Zionist media outlets.1 Over the 49 days of the 2014 Gaza War, a number of violent attacks were committed across the Palestinian territories; two Palestinians were killed in the occupied West Bank village of Beit Ommar during a protest against the assault on Gaza, while bodies piled up on the emergency room floors of Al-Shifa Hospital, overwhelmed by the number of casualties. Our records of this time are held in part by social media, which served as an essential medium for distributing images and information that show the effects of airstrikes on children, mothers, fathers, urban infrastructure, heritage sites, and hospitals.

To this day, our reliance on social media as an archive of political violence (and political resistance) forces us to reckon with the manifold issues of having social media platforms act as keepers of these records. At any given point, the contents of a user’s profile can be subjected to a “set of abstract and seemingly neutral laws, regulations, and practices” (Azoulay, 2019, 187) that can algorithmically censor and remove content according to rapidly and arbitrarily shifting community guidelines. At the heart of these platforms, we continue to see an extension of what Ariella Azoulay calls, “the kernel of imperialism’s archival modus operandi”, that is, the establishment of an “archival regime” wherein “existing forms of being-together and of inhabiting the world are violated through the separation of objects from people” (2019, 174). This user generated content is thus transformed in line with externalized categories that determine how contents are preserved, appropriated, displaced, exploited, and erased. Though it would be somewhat inaccurate to consider social media platforms as ‘proper archives’, such systems are built upon imperial and capitalist infrastructures and governed by similar “ruling technologies” (Azoulay, 2019, 170), including, but not limited to, hashtags and other forms of categorizing data. What makes them distinct from traditional archives, however, is that they are oriented by the demands of datafication such that the unstoppable race for documentation and multiplication is seemingly pursued for its own sake, with no sense of the long-term uses of these contents after they have served their immediate purpose. Resisting these archival regimes, however, proves to be quite an urgent and challenging problem for our contemporary era. What kinds of aesthetic and political interventions, then, can be made to these ruling technologies in order to retain, preserve, and provide access to the contents laden in these vast data repositories?

Taking the work of artist and scholar Laila Shereen Sakr (AKA VJ Um Amal) as the starting point of this inquiry, I turn to her piece, #Gaza Visual Narrative by a Cyborg: Images Tweeted by Hashtag, which recreates the viral image of the boys on the beach as an interactive mosaic using a data set of over 6,000 tweets collected from Twitter over one hour on July 26, 2014 .

![]()

Figure 2: A screenshot of #Gaza Visual Narrative's mosaic. Source: https://vjumamel.com/gaza-viz/index.php

To this day, our reliance on social media as an archive of political violence (and political resistance) forces us to reckon with the manifold issues of having social media platforms act as keepers of these records. At any given point, the contents of a user’s profile can be subjected to a “set of abstract and seemingly neutral laws, regulations, and practices” (Azoulay, 2019, 187) that can algorithmically censor and remove content according to rapidly and arbitrarily shifting community guidelines. At the heart of these platforms, we continue to see an extension of what Ariella Azoulay calls, “the kernel of imperialism’s archival modus operandi”, that is, the establishment of an “archival regime” wherein “existing forms of being-together and of inhabiting the world are violated through the separation of objects from people” (2019, 174). This user generated content is thus transformed in line with externalized categories that determine how contents are preserved, appropriated, displaced, exploited, and erased. Though it would be somewhat inaccurate to consider social media platforms as ‘proper archives’, such systems are built upon imperial and capitalist infrastructures and governed by similar “ruling technologies” (Azoulay, 2019, 170), including, but not limited to, hashtags and other forms of categorizing data. What makes them distinct from traditional archives, however, is that they are oriented by the demands of datafication such that the unstoppable race for documentation and multiplication is seemingly pursued for its own sake, with no sense of the long-term uses of these contents after they have served their immediate purpose. Resisting these archival regimes, however, proves to be quite an urgent and challenging problem for our contemporary era. What kinds of aesthetic and political interventions, then, can be made to these ruling technologies in order to retain, preserve, and provide access to the contents laden in these vast data repositories?

Taking the work of artist and scholar Laila Shereen Sakr (AKA VJ Um Amal) as the starting point of this inquiry, I turn to her piece, #Gaza Visual Narrative by a Cyborg: Images Tweeted by Hashtag, which recreates the viral image of the boys on the beach as an interactive mosaic using a data set of over 6,000 tweets collected from Twitter over one hour on July 26, 2014 .

Figure 2: A screenshot of #Gaza Visual Narrative's mosaic. Source: https://vjumamel.com/gaza-viz/index.php

From this narrow slice of time, Sakr examines five sets of hashtags in particular – #GazaUnderAttack, #Gaza, #48KMarch, #PalestineResists, and #ProtectiveEdge – which she re-visualizes using R–Shief, a digital archive created by Sakr to “collect, analyze, and visualize social media content”.2 Rather than solely relying on formal elements such as color or hue to determine the form of the resulting image, Sakr’s design process involves, “pulling culturally significant content and prioritizing images that are most popular” (Sakr, 2015, 9), allowing the user to identify common trends within each hashtag. Here in her mosaic, the ghostly silhouettes of these three boys are traced together by an array of photographs, sketches, and posters that have been aggregated from these hashtags. By appropriating this material for alternate artistic and archival purposes, Sakr advances the possibility of using social media platforms to better grasp how networks of solidarity are formed, how public imaginaries of historiography and temporality are constituted, and how digital platforms like Twitter instantiate a structure of remembrance that bleeds into our collective forms of political recollection and amnesia.

As the user hovers their cursor across the tiles of this mosaic, various images and their associated hashtags pop up, providing a glimpse into this large data set. It is an intensely affective experience to engage with this work, and as I scan the tiles, a sense of numbness washes over me, having been inundated with a surplus of images, videos, stories, cartoons, and posters since the start of Israel’s latest and most intense wave of ethnic cleansing in Gaza. At the top of the mosaic, I encounter an image of the Erasmusbrug in Rotterdam filled with demonstrators, sparking my own memory of marching across this very bridge on October 22nd, 2023. The traces of violence, the reminders of political activism from a decade prior, the familiar infographics that describe the abhorrent conditions of life in Gaza are recollected here in this set of images. Taking a moment of pause, I am reminded of another more recent image of three boys targeted by an airstrike in Gaza in March 2024.

![]()

Figure 3: Video screenshot of footage aired by Al Jazeera in March 2024 showing three Palestinian men walking in Khan Younis immediately before being targeted in an Israeli airstrike. The full video can be seen here (at your own discretion)

The resemblance is startling, from the surveillant vantage point of the camera to the faceless silhouettes of the victims, again capturing the moments before these lives were obliterated by a drone strike. The associations that this work engenders is not only a consequence of our current historical position, but rather is afforded by the technological-mediations of R-Shief, which puts the user in a privileged subject position within the hashtag-as-archive; one that would otherwise be inaccessible through conventional forms of data scraping and scrolling.

Clicking along the top row of R-Shief’s interface onto one of the five hashtags, the user can parse this collection into smaller groupings. #Gaza is perhaps the most polysemic of the bunch, encompassing a wide range of communities, each with their own distinct semantic nuances and sometimes oppositional political positions (Sakr, 2015, 10). While some of the images tagged with #Gaza demand an end to Israel’s occupation and settler-colonial violence, others use the hashtag to justify innocent slaughter in the name of Israel’s ‘national security’. Sakr’s decision to strip these images of any hypertextual information (username, time, location) resists the identificatory logic of datafication, which seeks to pin down each user to a proper name and proper place. Sakr herself has acknowledged that her interest, “is not to identify ‘who’ the people are ontologically, but how they form networks of solidarity” (Sakr, 2015, 2), highlighting the different and overlapping affective and discursive registers that are present within a hashtag. The hashtag thus surpasses its initial role as a way of labelling online content by becoming evocative of shared ideals, collective narratives, and broader conversations around social justice movements globally (Dobrin, 2020), functioning as both a method of accumulating personal accounts, critiques, and relevant documents and locus gives form to our public imaginaries of political struggle.

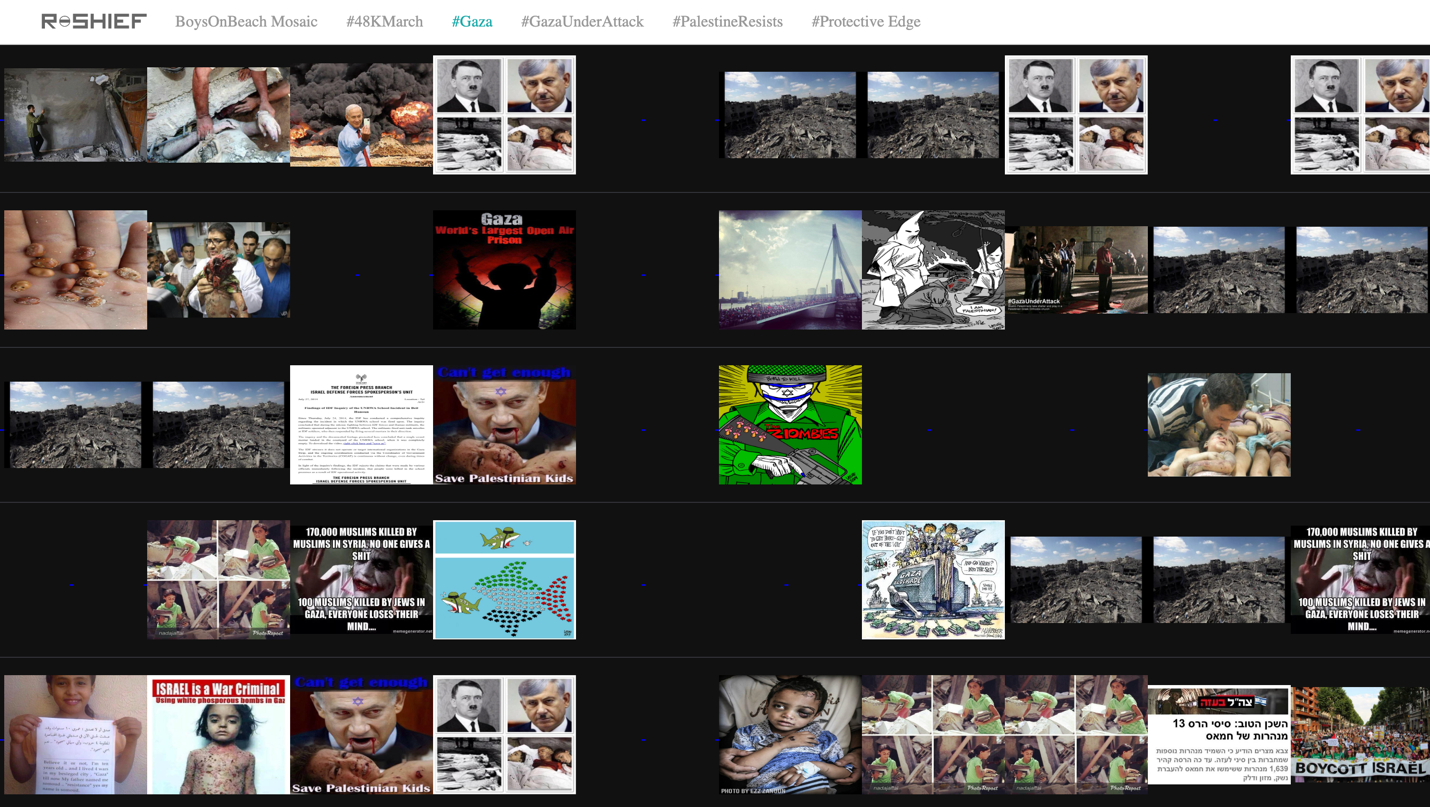

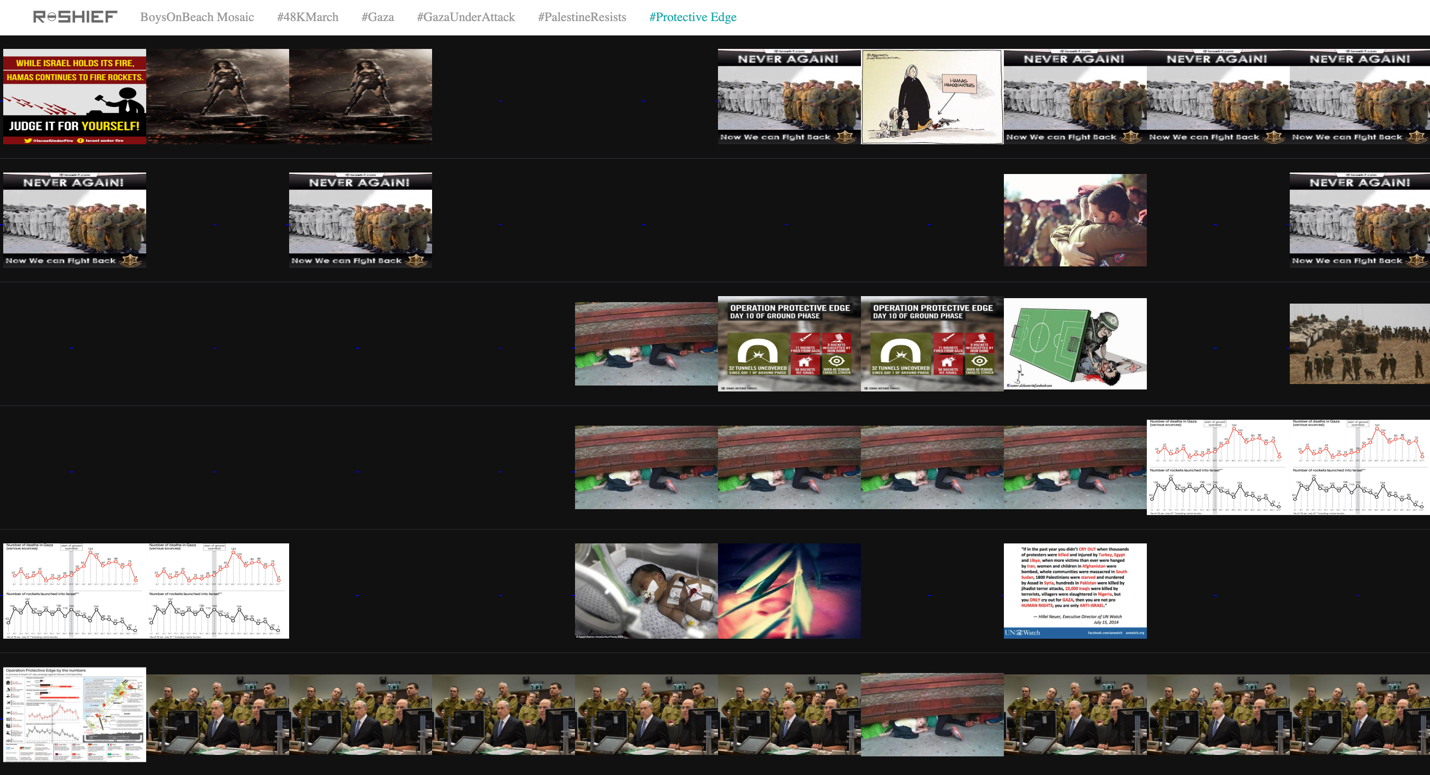

As with any archive, the documents and records held within this repository provide the foundation upon which history is written. Here in these hashtags, however, the practice of historiography is taken up by users themselves in compliance with the tools and infrastructure afforded by Twitter. #Gaza, on the one hand, features an array of user generated content ranging from infographics about the previous assaults on Gaza to memes comparing Netanyahu and Hitler (Figure 4), many of which rely on an implicit notion of ‘history repeating itself’ once again. Turning to another hashtag, #ProtectiveEdge (the Israeli army’s name for the assault on Gaza) expresses a markedly different conception of historical time, encapsulated in the frequently tweeted image of a row of Jewish prisoners in concentration camps merging into a row of IDF soldiers bearing the captions “Never Again” and “Now we can fight back” (Figure 5). The popularity of this image amongst pro-Israeli voices enshrines an idea of historical time in which the present is both a definitive break from the violence of history and an anachronic fusion of past and present. Held within these two hashtags are two conflicting conceptions of historical time that bring to the fore the ways in which history is instrumentalized to promote the political interests of each community and to maintain control over their social reality.

![]() Figure 4: Screenshots of subcategory #Gaza. Source: https://vjumamel.com/gaza-viz/hash2.php

Figure 4: Screenshots of subcategory #Gaza. Source: https://vjumamel.com/gaza-viz/hash2.php

![]()

Figure 5: Screenshots of subcategory #Gaza. Source: https://vjumamel.com/gaza-viz/hash5.php

As the user hovers their cursor across the tiles of this mosaic, various images and their associated hashtags pop up, providing a glimpse into this large data set. It is an intensely affective experience to engage with this work, and as I scan the tiles, a sense of numbness washes over me, having been inundated with a surplus of images, videos, stories, cartoons, and posters since the start of Israel’s latest and most intense wave of ethnic cleansing in Gaza. At the top of the mosaic, I encounter an image of the Erasmusbrug in Rotterdam filled with demonstrators, sparking my own memory of marching across this very bridge on October 22nd, 2023. The traces of violence, the reminders of political activism from a decade prior, the familiar infographics that describe the abhorrent conditions of life in Gaza are recollected here in this set of images. Taking a moment of pause, I am reminded of another more recent image of three boys targeted by an airstrike in Gaza in March 2024.

Figure 3: Video screenshot of footage aired by Al Jazeera in March 2024 showing three Palestinian men walking in Khan Younis immediately before being targeted in an Israeli airstrike. The full video can be seen here (at your own discretion)

The resemblance is startling, from the surveillant vantage point of the camera to the faceless silhouettes of the victims, again capturing the moments before these lives were obliterated by a drone strike. The associations that this work engenders is not only a consequence of our current historical position, but rather is afforded by the technological-mediations of R-Shief, which puts the user in a privileged subject position within the hashtag-as-archive; one that would otherwise be inaccessible through conventional forms of data scraping and scrolling.

Clicking along the top row of R-Shief’s interface onto one of the five hashtags, the user can parse this collection into smaller groupings. #Gaza is perhaps the most polysemic of the bunch, encompassing a wide range of communities, each with their own distinct semantic nuances and sometimes oppositional political positions (Sakr, 2015, 10). While some of the images tagged with #Gaza demand an end to Israel’s occupation and settler-colonial violence, others use the hashtag to justify innocent slaughter in the name of Israel’s ‘national security’. Sakr’s decision to strip these images of any hypertextual information (username, time, location) resists the identificatory logic of datafication, which seeks to pin down each user to a proper name and proper place. Sakr herself has acknowledged that her interest, “is not to identify ‘who’ the people are ontologically, but how they form networks of solidarity” (Sakr, 2015, 2), highlighting the different and overlapping affective and discursive registers that are present within a hashtag. The hashtag thus surpasses its initial role as a way of labelling online content by becoming evocative of shared ideals, collective narratives, and broader conversations around social justice movements globally (Dobrin, 2020), functioning as both a method of accumulating personal accounts, critiques, and relevant documents and locus gives form to our public imaginaries of political struggle.

As with any archive, the documents and records held within this repository provide the foundation upon which history is written. Here in these hashtags, however, the practice of historiography is taken up by users themselves in compliance with the tools and infrastructure afforded by Twitter. #Gaza, on the one hand, features an array of user generated content ranging from infographics about the previous assaults on Gaza to memes comparing Netanyahu and Hitler (Figure 4), many of which rely on an implicit notion of ‘history repeating itself’ once again. Turning to another hashtag, #ProtectiveEdge (the Israeli army’s name for the assault on Gaza) expresses a markedly different conception of historical time, encapsulated in the frequently tweeted image of a row of Jewish prisoners in concentration camps merging into a row of IDF soldiers bearing the captions “Never Again” and “Now we can fight back” (Figure 5). The popularity of this image amongst pro-Israeli voices enshrines an idea of historical time in which the present is both a definitive break from the violence of history and an anachronic fusion of past and present. Held within these two hashtags are two conflicting conceptions of historical time that bring to the fore the ways in which history is instrumentalized to promote the political interests of each community and to maintain control over their social reality.

Figure 4: Screenshots of subcategory #Gaza. Source: https://vjumamel.com/gaza-viz/hash2.php

Figure 4: Screenshots of subcategory #Gaza. Source: https://vjumamel.com/gaza-viz/hash2.php

Figure 5: Screenshots of subcategory #Gaza. Source: https://vjumamel.com/gaza-viz/hash5.php

Crucially, there are a number of missing images and blank spaces across the various webpages of #Gaza Visual Narrative that have potentially been deleted by users, removed by content moderators on Twitter, or perhaps corrupted by glitches. What images and stories have been lost? What marginal positions might have been pushed further still such that they have fallen from view? By maintaining these gaps and absences in this remediated constellation of images, R-Shief positions the hashtag not as a ‘living archive’ but as a graveyard of political life, a repository of undead material that awaits its resuscitation from a second death. In the absence of a trusted guardian of this material, Sakr disturbs the resting place of these images, stripping them from the ‘proper place’ to which they were assigned. Sakr’s re-contextualization thereby influences the status of these images, giving a second life to these otherwise forgotten bits of data by re-animating them through an interactive interface. At the same time, Sakr literally re-members the maimed bodies of these boys by reconstructing their ghostly silhouettes out of the remnants of the political fallout following their death. Their bodies are no longer their own, but rather become an assemblage of contrasting ideologies, affects, and discursive positions.

As platforms guided by asymmetrical power relations and driven by arbitrary logics and datafication practices, the governing logics of social media are somewhat antithetical to the approaches required for long-term historical preservation. In turn, we must remain critically vigilant to the ways in which the technologies of social media classify, sort, and subject these documents to their own specific temporal, juridical, and archival regimes. Though Sakr herself does not attempt to supply a clear resolution to this problem, her creative practice unsettles and undermines the dominant categories of these platforms by remediating the contents of these hashtags in a liminal configuration, somewhere between the place they have been assigned to and the place they transgressively occupy on R-Shief. In doing so, the displacement of the images from one context to the next can be understood as a kind of fugitive motion, one which may assist in the survival of these images as they are continuously put under the threat of becoming lost. By reusing the hashtag for ulterior political and aesthetic purposes, #Gaza Visual Narrative demonstrates that there is simply no place ‘outside’ of the archival regimes that govern social media platforms like Twitter, merely ways of redoubling and reconfiguring its logics.

As platforms guided by asymmetrical power relations and driven by arbitrary logics and datafication practices, the governing logics of social media are somewhat antithetical to the approaches required for long-term historical preservation. In turn, we must remain critically vigilant to the ways in which the technologies of social media classify, sort, and subject these documents to their own specific temporal, juridical, and archival regimes. Though Sakr herself does not attempt to supply a clear resolution to this problem, her creative practice unsettles and undermines the dominant categories of these platforms by remediating the contents of these hashtags in a liminal configuration, somewhere between the place they have been assigned to and the place they transgressively occupy on R-Shief. In doing so, the displacement of the images from one context to the next can be understood as a kind of fugitive motion, one which may assist in the survival of these images as they are continuously put under the threat of becoming lost. By reusing the hashtag for ulterior political and aesthetic purposes, #Gaza Visual Narrative demonstrates that there is simply no place ‘outside’ of the archival regimes that govern social media platforms like Twitter, merely ways of redoubling and reconfiguring its logics.

Works Cited

- Azoulay, A. A. (2019). Potential history: Unlearning imperialism. Verso Books.

- Dobrin, D. (2020). The hashtag in digital activism: A cultural revolution. Journal of Cultural Analysis and Social Change, 5(1), 1-14.

- Shereen Sakr, L. (2015). A Virtual Body Politic on #Gaza: The Mobilization of Information Patterns. Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.31165/nk.2015.82.373

Jamil Fiorino-Habib

Jamil Fiorino-Habib is a lecturer in Media & Culture at the University of Amsterdam, specializing in film studies and media aesthetics. Having recently obtained his rMA in Media Studies from UvA, Jamil's current research projects elaborate on his interests in political subjectivity, identity, and play, incorporating elements of queer theory and critical theory to explore the evolving boundaries of digital media culture. Making use of unique transdisciplinary pedagogies, Jamil's work explores the intersections of pop culture and sub-culture, the hegemonic and the subversive, and the impacts of cultural imperialism in a globalized media landscape. In tandem with his academic research, Jamil also participates in a variety of grassroots community-centred collectives within the Netherlands, where he helps strategize and develop plans in pursuit of radical system change.