Alessia Corti and TÄRA

Sensory Archive of Palestine and Quiet Solidarities from a Balcony

“I keep smelling the scent of home in the diaspora.

You left me your clothes and your story,

and I will take care of them.

But unfortunately, this world hasn’t changed,

it still hasn’t liberated”.

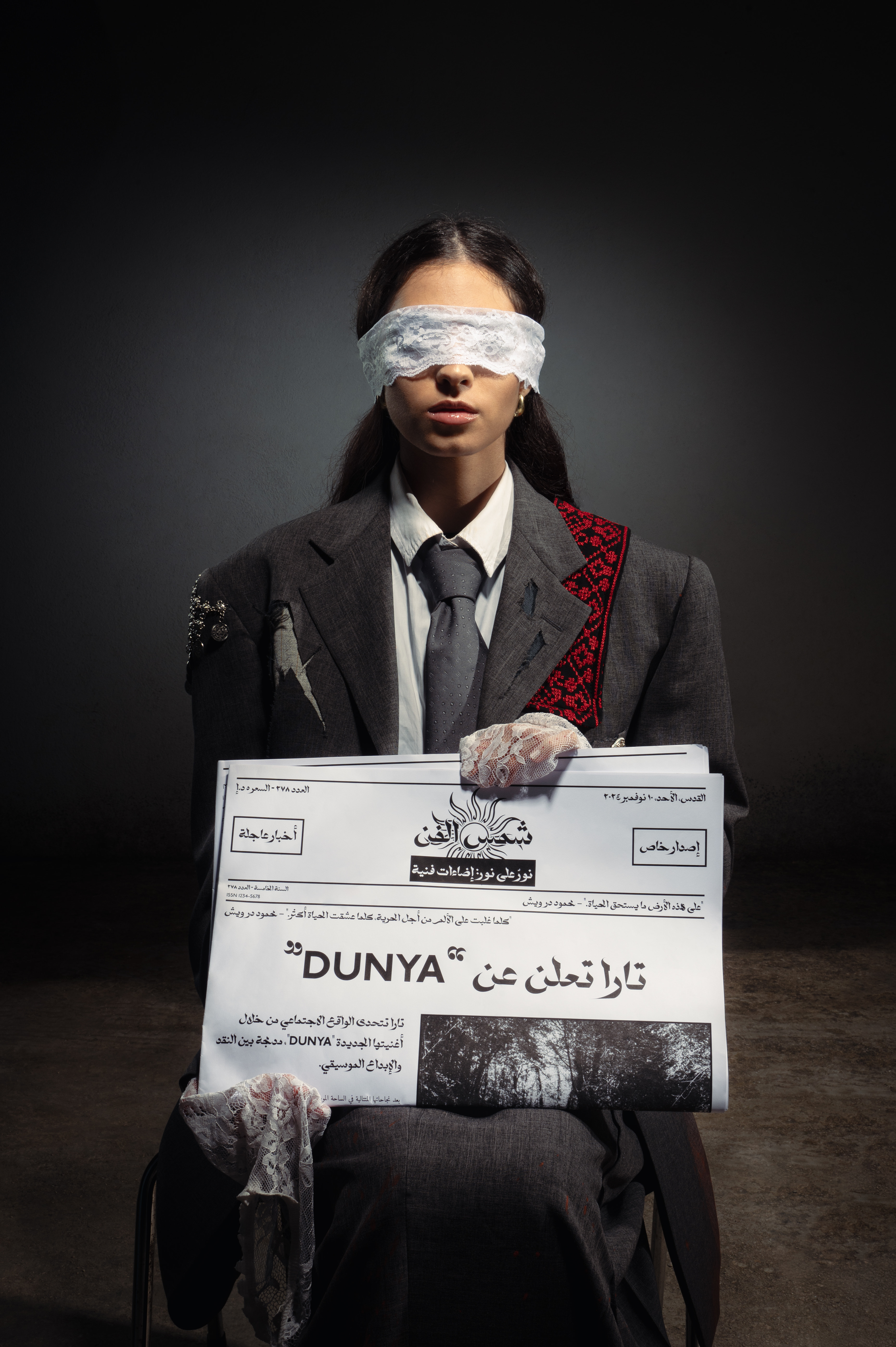

This spoken prologue, originally in Arabic, is how TÄRA opens the music video of her song Dunya. As a Palestinian-Italian artist, her music is deeply rooted in her heritage and personal story: she writes in Italian and Arabic, blending the two languages within alternative R&B, creating what she calls “Arab’nB”. Though she has never set foot in the land she invokes, her voice insists on carrying its scents, stories, and sounds. The fragments of family memory and the familiarity of the home, its rhythms and narratives, become the sonic texture of her work.

TÄRA is part of the 7.4 million Palestinians living in the diaspora. Her artistic practice is not only personal expression: it becomes a form of archiving, of keeping alive what settler colonialism seeks to erase.

When I asked how her multiple identities – being Palestinian, Italian, and living in the diaspora – influence her practice, she replied simply: “After all it’s just me, it’s who I am”. Identity is not a strategy but a lived embodiment. Her music does not perform duality; it inhabits it.

One moment from our conversation stayed with me. When I asked how much of her work comes from political urgency and how much from intimate experience, TÄRA replied: “Non l’ho mai associato a una cosa politica, ma umana” (“I never thought of it as political, but human”).

For days, this sentence echoed in my mind. For many of us, “the personal is political” comes immediately to mind when speaking of colonialism and oppression. TÄRA’s refusal of the word “political” perhaps reflects its association with opportunism and institutional frameworks. To call her work “human” insists that it is grounded in lived experience, in memory and longing, in the real lives of real people too often reduced to numbers. And yet, it is precisely because it is human that it is political. Under colonial repression, preserving culture is never neutral. To sing about Palestine, to wear Palestine, to breathe Palestine, is to affirm existence against erasure. As Fanon reminds us, colonialism dehumanizes; in such a context, insisting on the human is itself resistance. Here, the human and the political collapse into one another.

TÄRA is part of the 7.4 million Palestinians living in the diaspora. Her artistic practice is not only personal expression: it becomes a form of archiving, of keeping alive what settler colonialism seeks to erase.

When I asked how her multiple identities – being Palestinian, Italian, and living in the diaspora – influence her practice, she replied simply: “After all it’s just me, it’s who I am”. Identity is not a strategy but a lived embodiment. Her music does not perform duality; it inhabits it.

One moment from our conversation stayed with me. When I asked how much of her work comes from political urgency and how much from intimate experience, TÄRA replied: “Non l’ho mai associato a una cosa politica, ma umana” (“I never thought of it as political, but human”).

For days, this sentence echoed in my mind. For many of us, “the personal is political” comes immediately to mind when speaking of colonialism and oppression. TÄRA’s refusal of the word “political” perhaps reflects its association with opportunism and institutional frameworks. To call her work “human” insists that it is grounded in lived experience, in memory and longing, in the real lives of real people too often reduced to numbers. And yet, it is precisely because it is human that it is political. Under colonial repression, preserving culture is never neutral. To sing about Palestine, to wear Palestine, to breathe Palestine, is to affirm existence against erasure. As Fanon reminds us, colonialism dehumanizes; in such a context, insisting on the human is itself resistance. Here, the human and the political collapse into one another.

1. Fanon, On Violence, in The Wretched of the Earth.

This is why TÄRA’s music moves not only through lyrics but through the very textures and gestures of Palestinian life. Her art breathes Palestine also through symbols: the tatreez embroidery, the keffiyeh, the dabke. These symbols are living archives in themselves. The tatreez carries ancestral memory and rejection of settler colonialism: during the Nakba of 1948, women embroidered the motifs of their villages into clothing, preserving the places that the occupier tried to erase. To wear the tatreez is to insist: we exist. The dabke, whose name means “to stomp one’s feet”, began as the act of repairing cracked roofs and evolved into a communal dance of joy and refusal. For many Palestinians in the diaspora, stamping feet becomes a symbolic return and reclaiming of a land physically inaccessible. As Abu Hani explains: “They have stolen our land [stomp], forced us out of our homes [stomp], but our culture is something they cannot steal”.

Woven into TÄRA’s performances, these gestures do not stand apart from the music but extend it, making each song not only heard but inhabited – “lived at 360 degrees”, as she puts it. Her work becomes a sensory archive where sound, body, and fabric converge into resistance. Through such symbols, TÄRA’s art extends beyond music into a tactical, visual, and collective memory, becoming an unfinished archive – one that grows within each performance.

If symbols embody the archive, lyrics give it voice. In Dunya, TÄRA signs of the culture her ancestors entrusted to her: “Voices among the ruins, Seeds of immortality”. The song carries anger for a Palestine, and with it a world, not yet liberated. It is an anger against a world that shrugs, “mish faraa” – it doesn’t matter – as she sings through the chorus. But indifference, TÄRA reminds us, is not innocent. She calls it “omertà”, a term from mafia culture with no direct English equivalent, which evokes a silence rooted in complicity: the quiet allowance of injustice. By naming the global silence on Palestine as omertà, she indicts it as criminal, echoing Desmond Tutu’s words in the context of apartheid South Africa: “if you are neutral in situations of injustice you have chosen the side of the oppressor”.

Yet Dunya is not just anger. It is hope and resistance. By keeping her ancestors’ memories alive – the seeds that, even when buried deep, continue to grow – TÄRA affirms the resilience of the Palestinian people who resist the colonial violence and its (failed) attempt at erasing Palestine. The hope that Dunya embodies comes as strongly as ever in the last verse of the song:

Woven into TÄRA’s performances, these gestures do not stand apart from the music but extend it, making each song not only heard but inhabited – “lived at 360 degrees”, as she puts it. Her work becomes a sensory archive where sound, body, and fabric converge into resistance. Through such symbols, TÄRA’s art extends beyond music into a tactical, visual, and collective memory, becoming an unfinished archive – one that grows within each performance.

If symbols embody the archive, lyrics give it voice. In Dunya, TÄRA signs of the culture her ancestors entrusted to her: “Voices among the ruins, Seeds of immortality”. The song carries anger for a Palestine, and with it a world, not yet liberated. It is an anger against a world that shrugs, “mish faraa” – it doesn’t matter – as she sings through the chorus. But indifference, TÄRA reminds us, is not innocent. She calls it “omertà”, a term from mafia culture with no direct English equivalent, which evokes a silence rooted in complicity: the quiet allowance of injustice. By naming the global silence on Palestine as omertà, she indicts it as criminal, echoing Desmond Tutu’s words in the context of apartheid South Africa: “if you are neutral in situations of injustice you have chosen the side of the oppressor”.

Yet Dunya is not just anger. It is hope and resistance. By keeping her ancestors’ memories alive – the seeds that, even when buried deep, continue to grow – TÄRA affirms the resilience of the Palestinian people who resist the colonial violence and its (failed) attempt at erasing Palestine. The hope that Dunya embodies comes as strongly as ever in the last verse of the song:

بيجربوا يسكتوني

بس الحطة بتعلى

وبالليل كلهم نايمين

بس أحلامي صاحين

بيرسمونا وإحنا راجعين

But the keffiyeh rises

And at night, when everyone sleeps

My dreams stay awake

They draw us as we return.”

This is a call for the Palestinian right of return, one of the al-Thawabit al-Wataniyya, the fundamental principles that cannot be compromised in the struggle for Palestinian liberation. But a free Palestine is never an isolated event. To speak of Palestine is never only to speak of Palestine. As Zeyad el Nabolsy notes in his reading of Afro-Asian solidarity, to be Palestinian – or Indonesian or Angolan – was not to inhabit an isolated identity but to stand within a global front against oppression: “to express internationalist solidarity with all of the oppressed peoples of the world”.2 In this sense, Palestine is inevitably an internationalist question. Internationalism, in this view, was not a departure from the nation but its deepest grounding, because colonial systems are themselves interdependent, feeding on one another across continents. To reduce Palestine to an anomaly, to treat it as an exception in history, is to sever it from the very fabric of the anticolonial struggle of which it is part. TÄRA’s art resists this reduction.

2.

Zeyad el Nabolsy, Lotus and the Self-Representation of Afro-Asian Writers as the Vanguard of Modernity, p. 600

In one of her most recent tracks, she reinterprets the Italian antifascist anthem Bella Ciao in Palestinian dialect, Ya Helwe Ciao. She did not compose it; the text comes from anonymous Palestinian artists, but in recording and releasing it, TÄRA’s labor of love preserved it from obscurity.

“I thought it would be beautiful to unite the Italian resistance with the Palestinian one”, she told me. “I wanted to draw attention to what is shared in a time of division”. Through her voice, she created a bridge across histories of oppression, extending the anti-fascist anthem into an anti-colonial horizon.

This gesture belongs to a longer Italian tradition of musical solidarity with Palestine. In the 1970s, the student movement sang La Rossa Palestina, a militant anthem that called for raising the Palestinian and partisan flags together. Its chorus proclaimed that “ogni lotta aiuta un’altra lotta” – every struggle sustains another. TÄRA’s Ya Helwe Ciao stands in this genealogy, though in a different register. Where the earlier song shouted comradeship in the language of militancy, TÄRA braids comradeship through intimacy. Seated on a balcony in a quiet Italian town under the mountains, with a keffiyeh wrapped around her head and a Persian rug beneath her, she reimagines solidarity as resonance across everyday life. Her practice shows that solidarity does not always march; sometimes it sits, sings, and lingers, stitching together geographies of struggle through the most human textures of home and voice.

And yet as the Palestinian identity encapsulates, and as TÄRA also says, to exist is to resist. The domesticity of TÄRA’s acoustic Ya Helwe Ciao is not simply empathy, not a gesture of distant sympathy, but comradeship: an active wavering together of two histories of refusal, and a concrete indictment of a present-day Italy that remains one of the Israeli occupation’s top arms suppliers. To connect the Italian resistance with the Palestinian one is to insist that struggles separated by time and geography are bound by a shared refusal of oppression.

Such gestures reveal the Tricontinental potential of TÄRA’s practice. As the Tricontinental project emphasized, solidarity is not about collapsing distinctions but about recognizing the interdependencies between global systems of domination, and the collective refusal they generate. The Tricontinental imagined an internationalism grounded not in humanitarian pity but in mutual recognition and shared struggle – what Anne Garland Mahler calls trans-affective solidarity3: an ethical and affective resonance that moves across borders, languages, and bodies. In Mahler’s reading, this solidarity is not a fixed alliance but an intentionally fluid and open-ended collective becoming. It is the process of making a global subject formed not through state contracts or fixed categories of class and race, but through a radical openness that deliberately refuses closure – an openness sustained by the affective act of coming together itself. In the Tricontinental imaginary, the very act of producing affect – of making solidarity itself – was already a form of political praxis: both the means and the end of a struggle oriented towards a new global relation. Solidarity, in this sense, is both process and practice: a continuous attachment to one another across difference. TÄRA’s music echoes this ethos, through Ya Helwe Ciao but also in more fleeting, fugitive moments.

“I thought it would be beautiful to unite the Italian resistance with the Palestinian one”, she told me. “I wanted to draw attention to what is shared in a time of division”. Through her voice, she created a bridge across histories of oppression, extending the anti-fascist anthem into an anti-colonial horizon.

This gesture belongs to a longer Italian tradition of musical solidarity with Palestine. In the 1970s, the student movement sang La Rossa Palestina, a militant anthem that called for raising the Palestinian and partisan flags together. Its chorus proclaimed that “ogni lotta aiuta un’altra lotta” – every struggle sustains another. TÄRA’s Ya Helwe Ciao stands in this genealogy, though in a different register. Where the earlier song shouted comradeship in the language of militancy, TÄRA braids comradeship through intimacy. Seated on a balcony in a quiet Italian town under the mountains, with a keffiyeh wrapped around her head and a Persian rug beneath her, she reimagines solidarity as resonance across everyday life. Her practice shows that solidarity does not always march; sometimes it sits, sings, and lingers, stitching together geographies of struggle through the most human textures of home and voice.

And yet as the Palestinian identity encapsulates, and as TÄRA also says, to exist is to resist. The domesticity of TÄRA’s acoustic Ya Helwe Ciao is not simply empathy, not a gesture of distant sympathy, but comradeship: an active wavering together of two histories of refusal, and a concrete indictment of a present-day Italy that remains one of the Israeli occupation’s top arms suppliers. To connect the Italian resistance with the Palestinian one is to insist that struggles separated by time and geography are bound by a shared refusal of oppression.

Such gestures reveal the Tricontinental potential of TÄRA’s practice. As the Tricontinental project emphasized, solidarity is not about collapsing distinctions but about recognizing the interdependencies between global systems of domination, and the collective refusal they generate. The Tricontinental imagined an internationalism grounded not in humanitarian pity but in mutual recognition and shared struggle – what Anne Garland Mahler calls trans-affective solidarity3: an ethical and affective resonance that moves across borders, languages, and bodies. In Mahler’s reading, this solidarity is not a fixed alliance but an intentionally fluid and open-ended collective becoming. It is the process of making a global subject formed not through state contracts or fixed categories of class and race, but through a radical openness that deliberately refuses closure – an openness sustained by the affective act of coming together itself. In the Tricontinental imaginary, the very act of producing affect – of making solidarity itself – was already a form of political praxis: both the means and the end of a struggle oriented towards a new global relation. Solidarity, in this sense, is both process and practice: a continuous attachment to one another across difference. TÄRA’s music echoes this ethos, through Ya Helwe Ciao but also in more fleeting, fugitive moments.

3. Anne Garland Mahler, From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, Radicalism, and Transnational Solidarity, p. 109

In a recent Instagram reel, she sings a few acoustic lines of Bad Bunny’s Lo Que Le Pasó a Hawaii4 in Palestinian Arabic. Though brief and informal, this gesture opens a space where sounds travel across geographies, braiding together histories of colonialism in Puerto Rico, Hawai’i, and Palestine. Here, music is not only expression but reappropriation: an archive of shared dispossession, memory, and resistance.

4. The title of the song translates to “What happened to Hawaii”. In it, Bad Bunny draws a parallel between Puerto Rico and Hawaii to denounce U.S. colonialism. The song is both an anthem of resistance and a love letter to his island.

In this sense, TÄRA’s practice reveals what a musical archive can be: not a fixed object or a closed record, but a living, unfinished practice. Each performance is less a final statement than an opening – porous, incomplete, continuously reshaped in the present – through which struggles remain entangled and resistance keeps breathing.

“I want to be a voice”, TÄRA says. And she is. A voice through which this living archive breathes – carrying memory, refusing silence, and opening space for solidarities transcending time and space.

Rooted in her own story – the legacy of her ancestors and the life in the diaspora – TÄRA’s art weaves together the personal and the collective, placing the Palestinian struggle within a broader internationalist solidarity. It reaffirms the human that colonialism seeks, unsuccessfully, to erase and it reminds us that solidarity can also be shouted through quiet melodies of shared resistance sang from a balcony.

“I want to be a voice”, TÄRA says. And she is. A voice through which this living archive breathes – carrying memory, refusing silence, and opening space for solidarities transcending time and space.

Rooted in her own story – the legacy of her ancestors and the life in the diaspora – TÄRA’s art weaves together the personal and the collective, placing the Palestinian struggle within a broader internationalist solidarity. It reaffirms the human that colonialism seeks, unsuccessfully, to erase and it reminds us that solidarity can also be shouted through quiet melodies of shared resistance sang from a balcony.

Selected Bibliography

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2024). ‘Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) Presents the Conditions of the Palestinian Population on the Occasion of the World Population Day’. Available at: https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/portals/_pcbs/PressRelease/Press_En_WPD2024E.pdf

- Frantz Fanon (2004). ‘On Violence’. In: The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press, pp. 1–62.

- Christina Atik (2024). ‘Dabke: Resistance through movement’. Shado Magazine. Available at: https://shado-mag.com/articles/do/dabke-resistance-through-movement/

- Zeyad el Nabolsy (2020). ‘Lotus and the Self-Representation of Afro-Asian Writers as the Vanguard of Modernity’. Interventions, 23(4), pp.596–620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801x.2020.1784021.

- Zain Hussain (2024). ‘How top arms exporters have responded to the war in Gaza’. Stockholm International Peace Research Isntitute (SIPRI). Available at: https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2024/how-top-arms-exporters-have-responded-war-gaza

- Sabato Angieri (2025). ‘Sulle forniture di armi a Israele il governo mente’. Il Manifesto. Available at: https://ilmanifesto.it/lincontro-che-svela-le-bugie-del-governo-sulle-forniture-a-israele

- Anne Garland Mahler (2018). The “Colored and Oppressed” in Amerikkka. In From the Tricontinental to the Global South : race, radicalism, and transnational solidarity. 1st edn, pp. 106–159 Durham: Duke University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822371717.

Alessia Corti

Alessia Corti is an MSc student in Human Rights at LSE. Within the field of human rights, she is interested in refugee rights, gender, and their intersectionality, as well as broader questions of internationalism and postcolonial theory.

︎ ︎

Alessia Corti is an MSc student in Human Rights at LSE. Within the field of human rights, she is interested in refugee rights, gender, and their intersectionality, as well as broader questions of internationalism and postcolonial theory.

︎ ︎

TÄRA

TÄRA is redefining alternative R&B with her groundbreaking Arab’nB style, blending Arabic influences with modern R&B sounds.

Bilingual and deeply rooted in her Palestinian heritage, TÄRA’s music bridges cultures, creating a unique sonic and emotional experience. After a remarkable debut on X Factor Italia 2024, where she showcased her cultural fusion and earned millions of views, TÄRA has continued to solidify her position as a rising star.

︎ ︎

TÄRA is redefining alternative R&B with her groundbreaking Arab’nB style, blending Arabic influences with modern R&B sounds.

Bilingual and deeply rooted in her Palestinian heritage, TÄRA’s music bridges cultures, creating a unique sonic and emotional experience. After a remarkable debut on X Factor Italia 2024, where she showcased her cultural fusion and earned millions of views, TÄRA has continued to solidify her position as a rising star.

︎ ︎