Leili Sreberny-Mohammadi

Small Archive, Big Revolution:

Annabelle Sreberny’s Archive of Life in Iran 1976-1980

After the sudden death of my mother on the second-to-last day of the year 2022 I inherited many of her things. Amongst the carpets, clothes, candlesticks and other objects that made up her life and her home were a collection of letters and photographs that document an intimate period of her own life and of irrevocable change in Iran. It comprised a shoebox full of photos, a fraying beige folder packed full of postcards, stamped envelopes and letters typed on blue airmail paper and an A4 manila envelope of faded photo wallets with film negatives spilling out of them. Together the materials document the five years she lived in Iran between 1976-1980. During this time, she adapted to a new country, set up home with her husband and had her first child. She also participated in a revolution.

I do not suspect that my mother would describe these materials as an archive. They were simply her life. Although I am not certain, I assume the letters—addressed to her mother, grandmother, aunt and brother back home in the UK—came back into her possession after the death of her mother in 2006. Now they move from mother to daughter again, in death. These materials take on a new significance, a new weight and a new terminology. I describe the collection as an archive, an archive that narrates a significant period in my family history alongside a momentous period in the history of Iran. The contents are at once personal and political, intimate and social. Traversing these multiple states, they offer an inclusive way to think about the family archive, not just as personal and singular but simultaneously deeply enmeshed in its historical moment via the materials and their properties and the stories that the items hold.1 In this case, the collection holds both the “small” history of a period of time in my family narrative (indeed of a family I was not yet part of) and a “big” history of Iran’s revolution.2 This collection is both a route to narrate, organise and process significant moments in my family history and it is much more than that. It is an archive that contributes to understandings of women’s experiences of the revolution, that complicates and adds to the cacophony of writings about the era, and that integrates the hope and potency of the ideological struggles at the heart of the revolution. My mother’s point of view is also particular and distinct; she is a young, British Jewish woman, an intellectual, a leftist, and a feminist.

I do not suspect that my mother would describe these materials as an archive. They were simply her life. Although I am not certain, I assume the letters—addressed to her mother, grandmother, aunt and brother back home in the UK—came back into her possession after the death of her mother in 2006. Now they move from mother to daughter again, in death. These materials take on a new significance, a new weight and a new terminology. I describe the collection as an archive, an archive that narrates a significant period in my family history alongside a momentous period in the history of Iran. The contents are at once personal and political, intimate and social. Traversing these multiple states, they offer an inclusive way to think about the family archive, not just as personal and singular but simultaneously deeply enmeshed in its historical moment via the materials and their properties and the stories that the items hold.1 In this case, the collection holds both the “small” history of a period of time in my family narrative (indeed of a family I was not yet part of) and a “big” history of Iran’s revolution.2 This collection is both a route to narrate, organise and process significant moments in my family history and it is much more than that. It is an archive that contributes to understandings of women’s experiences of the revolution, that complicates and adds to the cacophony of writings about the era, and that integrates the hope and potency of the ideological struggles at the heart of the revolution. My mother’s point of view is also particular and distinct; she is a young, British Jewish woman, an intellectual, a leftist, and a feminist.

1. Woodham et al (2017) propose a capacious definition of the family archive which includes material objects and other inherited items amongst the documents more traditionally associated with archival practices. I appreciate this definition and thus include other objects here, but ultimately it is this specific collection which I now steward beyond the purview of the family and the home. What is particularly enthralling is many letters references various items which my parents acquired as they set up home in Tehran that were later carried to new homes and eventually to mine.

Woodham, A., King, L., Gloyn, L., Crewe, V., & Blair, F. (2017). We Are What We Keep: The “Family Archive”, Identity and Public/Private Heritage. Heritage & Society, 10(3), 203–220.

2. My parents went on to write the book Small Media, Big Revolution, Communication, Culture, and the Iranian Revolution. The book looks at how small media, such as cassette tapes and leaflets, rather than mass media, circulated and ultimately catapulted the revolution forward. I draw upon the title here to consider the small stories (of families, of regular lives) and big histories (of political upheaval) that this archive holds.

Sreberny-Mohammadi, A and Mohammadi, A, Small Media, Big Revolution, Communication, Culture, and the Iranian Revolution, 1994, The University of Minnesota Press

Woodham, A., King, L., Gloyn, L., Crewe, V., & Blair, F. (2017). We Are What We Keep: The “Family Archive”, Identity and Public/Private Heritage. Heritage & Society, 10(3), 203–220.

2. My parents went on to write the book Small Media, Big Revolution, Communication, Culture, and the Iranian Revolution. The book looks at how small media, such as cassette tapes and leaflets, rather than mass media, circulated and ultimately catapulted the revolution forward. I draw upon the title here to consider the small stories (of families, of regular lives) and big histories (of political upheaval) that this archive holds.

Sreberny-Mohammadi, A and Mohammadi, A, Small Media, Big Revolution, Communication, Culture, and the Iranian Revolution, 1994, The University of Minnesota Press

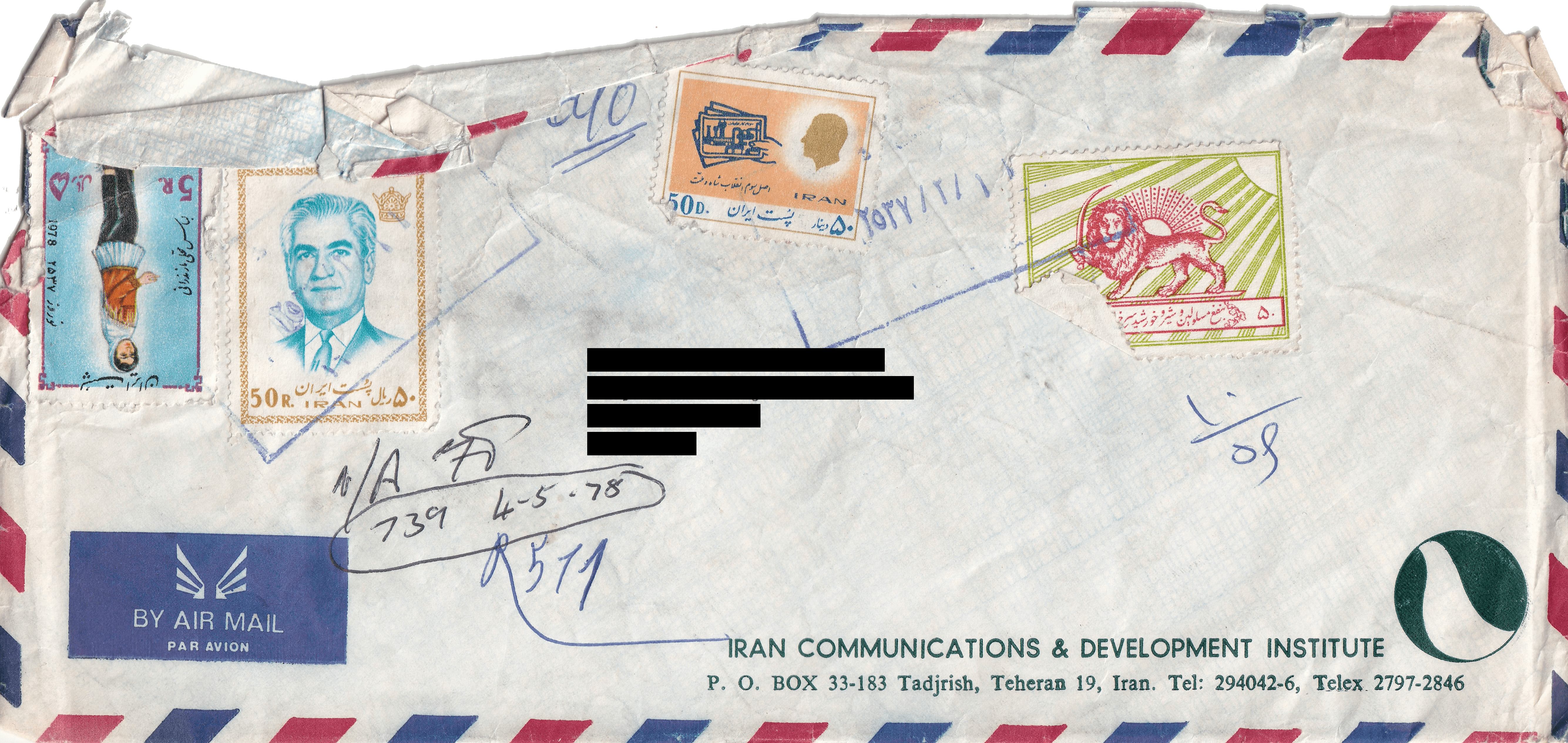

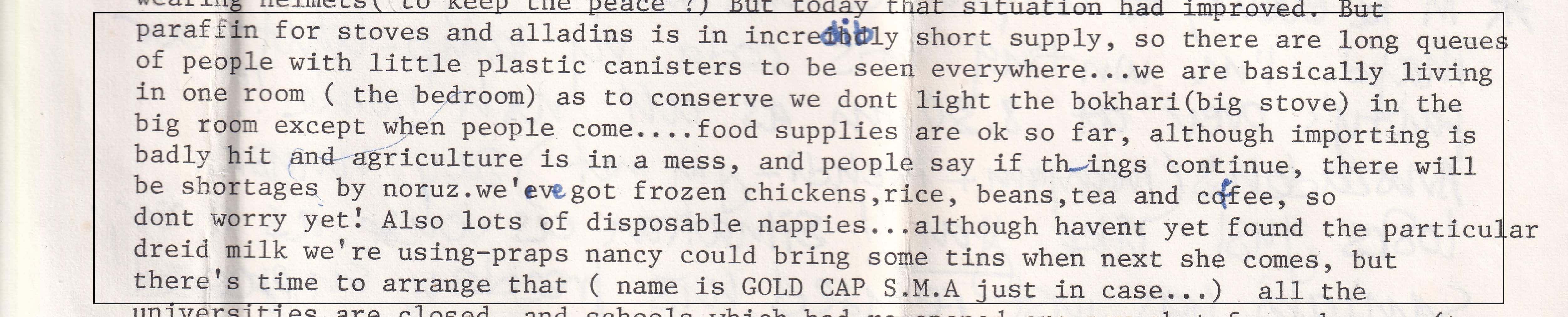

Her correspondence is an intimate dialogue with her family back home in London. She writes about her time adjusting to a new country and new job, trying to find meaningful work as an academic in a structure that does not value it. She describes her frustrations at the rhythm of nonsensical bureaucracies; the challenge of simply collecting a shipment of her belongings turns into a three-month long ordeal. There are also letters that span and reveal her first pregnancy. They express the very normal concerns and observations of a first-time mother delighting in her growing baby. As the chaos of the revolutions deepens, she writes about the impact on everyday life when limited electricity and food shortages become the norm. She begins to wonder if she will be able to purchase the important baby formula she has been feeding her daughter.

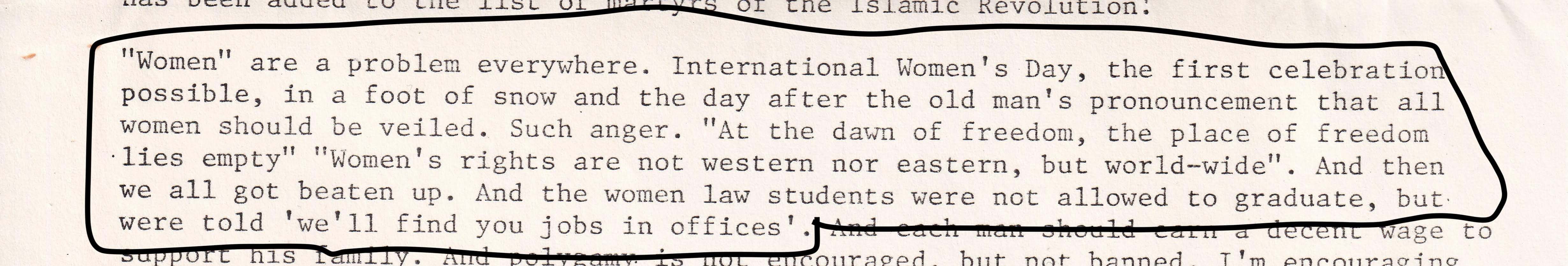

She notes the inefficient and uneven modernisation under the Shah that marked public revolt to his government. As the revolution intensifies, she astutely, and sometimes covertly, outlines the ideological flashpoints and disputed terrain of different revolutionary groups. Several photographs taken on International Women’s Day 1979, and during the six days of mobilisation that followed, capture fervent discussions between protestors likely arguing over Khomeini’s recent mandate on compulsory hijab.

![]()

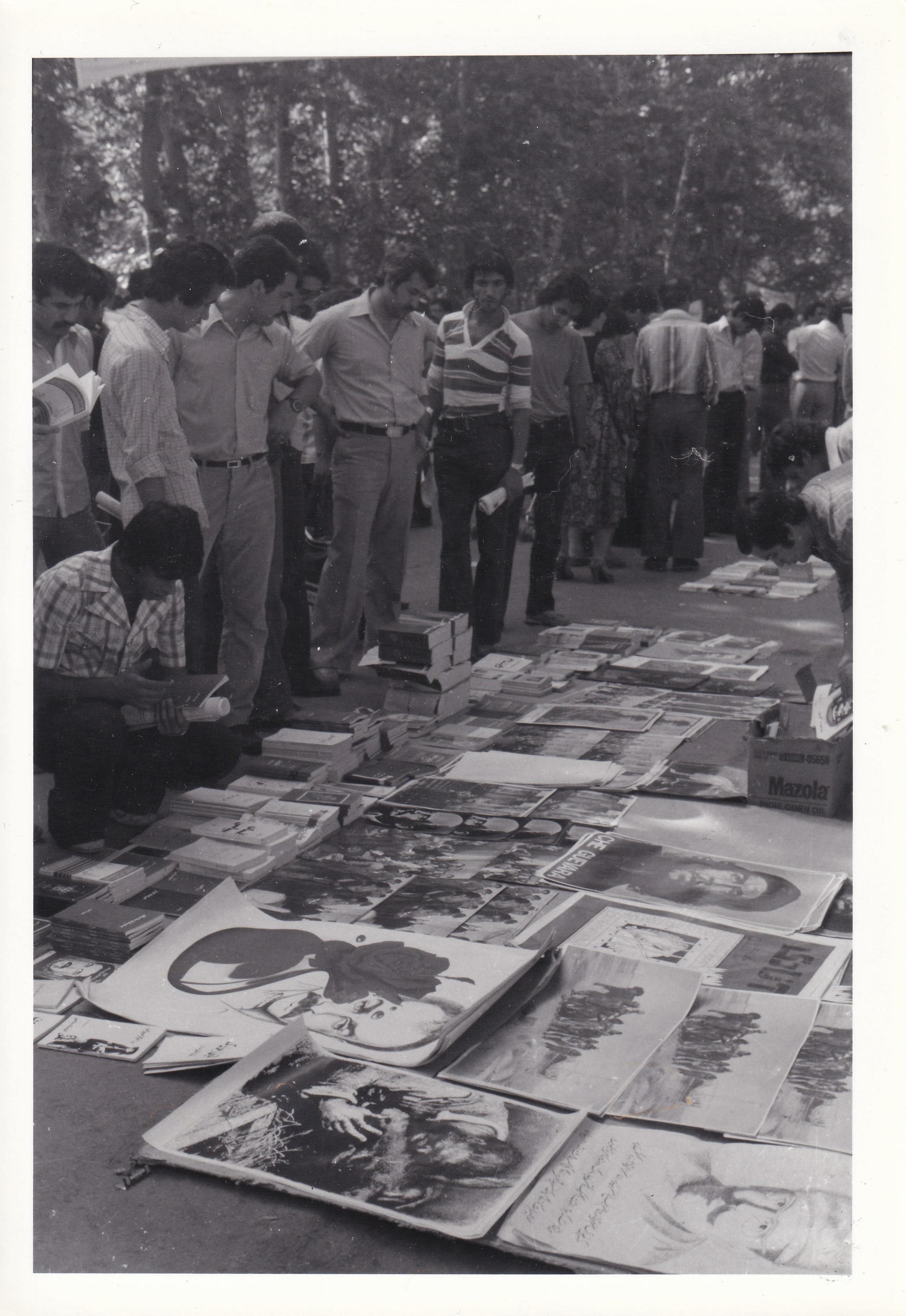

In the final letters there is confusion and unease over important decisions that loom ahead as it becomes increasingly clear that she cannot stay in Iran post-revolution. She also echoes my father’s choices and decisions, of how to integrate his academic work into professional contexts, how to contribute and participate to a potential new Iran, and the heartbreaks, disappointments and fears in the early dawn of the new Islamic Republic. The letters frequently weigh different plans—to return to London and build their family life or to continue her doctoral work back in New York. Alongside this tri-continental trajectory, her social and political convictions are ever-present. How to maintain solidarities between other social movements, other anti-imperial possibilities once the inclusive possibilities of the revolution were obstructed by Khomeini? In one letter she writes that she will be heading to the British embassy in the hopes of voting James Callaghan in as British PM because “he needs all the help he can against fascism”. Photos of revolutionary ephemera evidence yet more triadic relations; posters of Che Guevara and Lenin connect Iran with other twentieth century revolutions, a poster for Labour Day attest to support for workers’ rights and the working classes at the heart of revolutionary ambitions, other posters offer solidarity to Palestinian struggle, an ongoing relation expressed by numerous revolutionary factions.3

3. For an excellent outline of the shifting importance of Palestinian struggle amongst differing political groups both pre and post-revolution see Omid Montazeri’s Abandoned Legacy: The Left of Iran and Palestinians

The archive registers the abundant and changing visual culture of the revolutionary period. The blue airmail envelopes are stamped with portraits of the shah, his spectre looming even after his disposal. The photographs bear witness to a political effervescence; they show bodies coursing with adrenaline and marching on Tehran’s wide boulevards, others depleted and waiting in line for daily supplies, traces of violence on faces, buildings, and property. The pictures document revolutionary posters, books and publications, graffiti and street art. The images are not of the revolution but they are the revolution, the elements of daily life and of continued presence that propel revolution or what Asef Bayat describes as “the epidemic potential of street politics”.4 Her committed documentation is motivated by that same impulse, to be present, to witness, to participate.

4. Bayat, A Life As Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East, 2010, Amsterdam University Press, pg 12

My mother became a renowned academic and scholar with a long-term interest in the changing culture and politics of Iranian media. Engaged in multiple research commitments during her working life she rarely looked at these materials, but once retired she spent some time revisiting them. What emerged was a website produced in 2018 that documented what she dubbed “my revolutionary year”. The writing on the website is sparse, limited to captions and brief explanations of a selection of her photographs but it has already become a resource for researchers, artists and writers who continue to unearth and reconsider the trajectories of the revolution.

My goal with this archive is twofold. The first is to make her entire archive of photographs available as a digital resource so that it can remain accessible and supplement what is currently on her website. My second aim is to contribute to the field of visual memory by incorporating her photographs into a book publication. This would join other photobooks by both trained and amateur photographers, such as Kaveh Kazemi, Maryam Zand and Bahman Jalali, that provide a visual document of the revolution beyond the iconic images of fleeing or returning leaders.5 The book tells her story oriented by her position as an outsider adjusting to a new home while navigating the ecstasy of motherhood, the drudgery of domesticity, the precarity of academia and the intensities of political tumult. It will include photos and ephemera alongside the letters that narrate the sudden, swift, chaotic and conflictual events that unravelled during the revolutionary period.

My goal with this archive is twofold. The first is to make her entire archive of photographs available as a digital resource so that it can remain accessible and supplement what is currently on her website. My second aim is to contribute to the field of visual memory by incorporating her photographs into a book publication. This would join other photobooks by both trained and amateur photographers, such as Kaveh Kazemi, Maryam Zand and Bahman Jalali, that provide a visual document of the revolution beyond the iconic images of fleeing or returning leaders.5 The book tells her story oriented by her position as an outsider adjusting to a new home while navigating the ecstasy of motherhood, the drudgery of domesticity, the precarity of academia and the intensities of political tumult. It will include photos and ephemera alongside the letters that narrate the sudden, swift, chaotic and conflictual events that unravelled during the revolutionary period.

5.

See Haleh Anvari’s The Photographs that Defined the Iranian Revolution, a review of iconic images and photographic practices that emerged out of the era.

This archive speaks to the solidarities that remained constant until my mother died. Her letters reveal her internal conflict to remain a committed political subject with waning energy. They echo the jagged temporalities of our current moment: the urgency of halting a genocide, the longer trajectory of the climate crisis, and the steady beat of rising fascism. How does one keep going in the wake of such multiple and urgent crises? My responsibility now is caring for this collection and stewarding it from its boxes and back into the world. To do this I work in collaboration with my mother; her voice is as alive in me as it is in her letters, as vital, as generous and as steadfast in its commitments as ever.

Leili Sreberny-Mohammadi

Leili Sreberny-Mohammadi is an anthropologist with an interest in art and cultural production, transnationalism and the Middle East and Gulf countries. She was previously a fellow in Department of Sociology, LSE and an affiliate of the International Inequalities Institute. She currently teaches at the Courtauld Institute of Art.

︎

Leili Sreberny-Mohammadi is an anthropologist with an interest in art and cultural production, transnationalism and the Middle East and Gulf countries. She was previously a fellow in Department of Sociology, LSE and an affiliate of the International Inequalities Institute. She currently teaches at the Courtauld Institute of Art.

︎