Lucy Garbett

Social Reproduction

and the Uprising:

Palestinian

Feminist

Organising and Care Infrastructure

At the height of the first intifada nearly every

Palestinian refugee camp, village and town had a childcare centre run by the

various women’s committees established as the popular infrastructure of the

Palestinian resistance. The vital importance of such infrastructures both

theoretically and materially – the how and why they were established and what

they meant to the women – remains untold. This is despite a particular

nostalgia for the prominent role women played in the first intifada, as well as the

model of popular struggle the first intifada represented. Within

Palestinian academic and policy circles concepts such as a “resistance economy”

and “politically-driven economic development strategy” (Dana 2014:1) propose

alternative models of self-sufficiency and development. However the social

reproduction needs of such a model or a specific gendered understanding of what

a “resistance economy” could look like remain unaddressed despite the history

of such a practice within Palestinian struggle.

At the same time an archiving fever has arguably taken over Palestine with several archiving initiatives spearheaded by Palestinian institutions aiming to make digitally accessible records available. Although the personal collections of women activists who took part in the first intifada have been added to online archives, when I interviewed one of the founders of women’s committees in Palestine in the 1980s she expressed surprise at being asked about the childcare nurseries. “They were so important but you are the first person to ever ask me about them”, she told me. The presence of women in the first intifada is memorialised but the conditions which enabled such participation and presence are not. This raises important questions about how we remember, archive and memorialise significant moments in history. How can we archive the stages and the infrastructure established to enable a revolutionary moment in time?

The Women’s Committees: History and Approach

In the years running up to the first intifada, Palestinians located inside Palestine organised through volunteer work committees, trade unions and student committees. Women began to analyse some of the limitations of existing institutions such as trade unions to attend to and mobilise on behalf of the specific needs of women. In 1978 the Women’s Work Committee (WWC) was established by predominately middle-class women from the Ramallah area looking to mobilise working women and housewives in the WWC and the trade union movement. When the intifada began in earnest in 1987, an infrastructure had already been established with the women’s committees and other sectors of society. The massive popular mobilisation seen in Palestinian popular resistance to the Israeli occupation and colonisation of Palestine was organised through the establishment of popular committees in villages, camps and towns ranging from the field of education, health, agriculture and women’s committees.

The women’s committee firmly positioned themselves as different from the pre-existing women’s charity work institutions that primarily comprised women from large landowning and wealthy families. Moving beyond a charity framework, this generation of women worked within a different political trajectory that was about meeting the missing needs of women in the trade union struggle while furthering the understanding and needs of working Palestinian women. Two surveys were conducted to determine the focus of their strategy and work of the women’s committees (Hilterman 1991). They saw the urgency of organising women as part of the liberation struggle; part of that was trying to understand what women’s needs were and then organising around them in the refugee camps, in rural areas needed and attempting to provide alternatives such as teaching for the illiterate, salon training, food production programme, childcare, and textile training.

These various initiatives would feed into one another, not only as part of a wider holistic resistance network in the years leading up to the intifada but also as a women’s movement.

Through this grassroots work the women’s committees managed to organise and recruit a large number of women from various backgrounds and geographical locations inside Palestine (Hiltermann, 1991). By the 1980s this type of mobilisation was so successful that the Women’s Work Committee (WWC) split as each Palestinian political faction saw the benefit of establishing their own women’s committee to further their political program leading to four different women’s committees being established. Explaining their approach one interviewee told me:

At the same time an archiving fever has arguably taken over Palestine with several archiving initiatives spearheaded by Palestinian institutions aiming to make digitally accessible records available. Although the personal collections of women activists who took part in the first intifada have been added to online archives, when I interviewed one of the founders of women’s committees in Palestine in the 1980s she expressed surprise at being asked about the childcare nurseries. “They were so important but you are the first person to ever ask me about them”, she told me. The presence of women in the first intifada is memorialised but the conditions which enabled such participation and presence are not. This raises important questions about how we remember, archive and memorialise significant moments in history. How can we archive the stages and the infrastructure established to enable a revolutionary moment in time?

The Women’s Committees: History and Approach

In the years running up to the first intifada, Palestinians located inside Palestine organised through volunteer work committees, trade unions and student committees. Women began to analyse some of the limitations of existing institutions such as trade unions to attend to and mobilise on behalf of the specific needs of women. In 1978 the Women’s Work Committee (WWC) was established by predominately middle-class women from the Ramallah area looking to mobilise working women and housewives in the WWC and the trade union movement. When the intifada began in earnest in 1987, an infrastructure had already been established with the women’s committees and other sectors of society. The massive popular mobilisation seen in Palestinian popular resistance to the Israeli occupation and colonisation of Palestine was organised through the establishment of popular committees in villages, camps and towns ranging from the field of education, health, agriculture and women’s committees.

The women’s committee firmly positioned themselves as different from the pre-existing women’s charity work institutions that primarily comprised women from large landowning and wealthy families. Moving beyond a charity framework, this generation of women worked within a different political trajectory that was about meeting the missing needs of women in the trade union struggle while furthering the understanding and needs of working Palestinian women. Two surveys were conducted to determine the focus of their strategy and work of the women’s committees (Hilterman 1991). They saw the urgency of organising women as part of the liberation struggle; part of that was trying to understand what women’s needs were and then organising around them in the refugee camps, in rural areas needed and attempting to provide alternatives such as teaching for the illiterate, salon training, food production programme, childcare, and textile training.

These various initiatives would feed into one another, not only as part of a wider holistic resistance network in the years leading up to the intifada but also as a women’s movement.

Through this grassroots work the women’s committees managed to organise and recruit a large number of women from various backgrounds and geographical locations inside Palestine (Hiltermann, 1991). By the 1980s this type of mobilisation was so successful that the Women’s Work Committee (WWC) split as each Palestinian political faction saw the benefit of establishing their own women’s committee to further their political program leading to four different women’s committees being established. Explaining their approach one interviewee told me:

[1]Interview conducted by author, August 4th 2019

“We used to tell the women what do

you need? What kind of work? We would gather what people said and come to

agreement and majority of what the women need and start the first activity. We

would ask if there was a seamstress in the village- could she teach the others?

How much would we pay her? What would be everyone’s contribution? The group

would elect representatives that would attend meetings of all the regions

together to coordinate about their needs and challenges.[1]

Not only was this type of mobilisation key in later having a large number of women join the massive popular mobilisations of the first intifada, but it also signalled an important theoretical and organisational orientation that took social reproduction needs of mobilisation seriously and as a necessary step in organising.

Childcare Centers: A Mobilising Tool

Not only was this type of mobilisation key in later having a large number of women join the massive popular mobilisations of the first intifada, but it also signalled an important theoretical and organisational orientation that took social reproduction needs of mobilisation seriously and as a necessary step in organising.

Childcare Centers: A Mobilising Tool

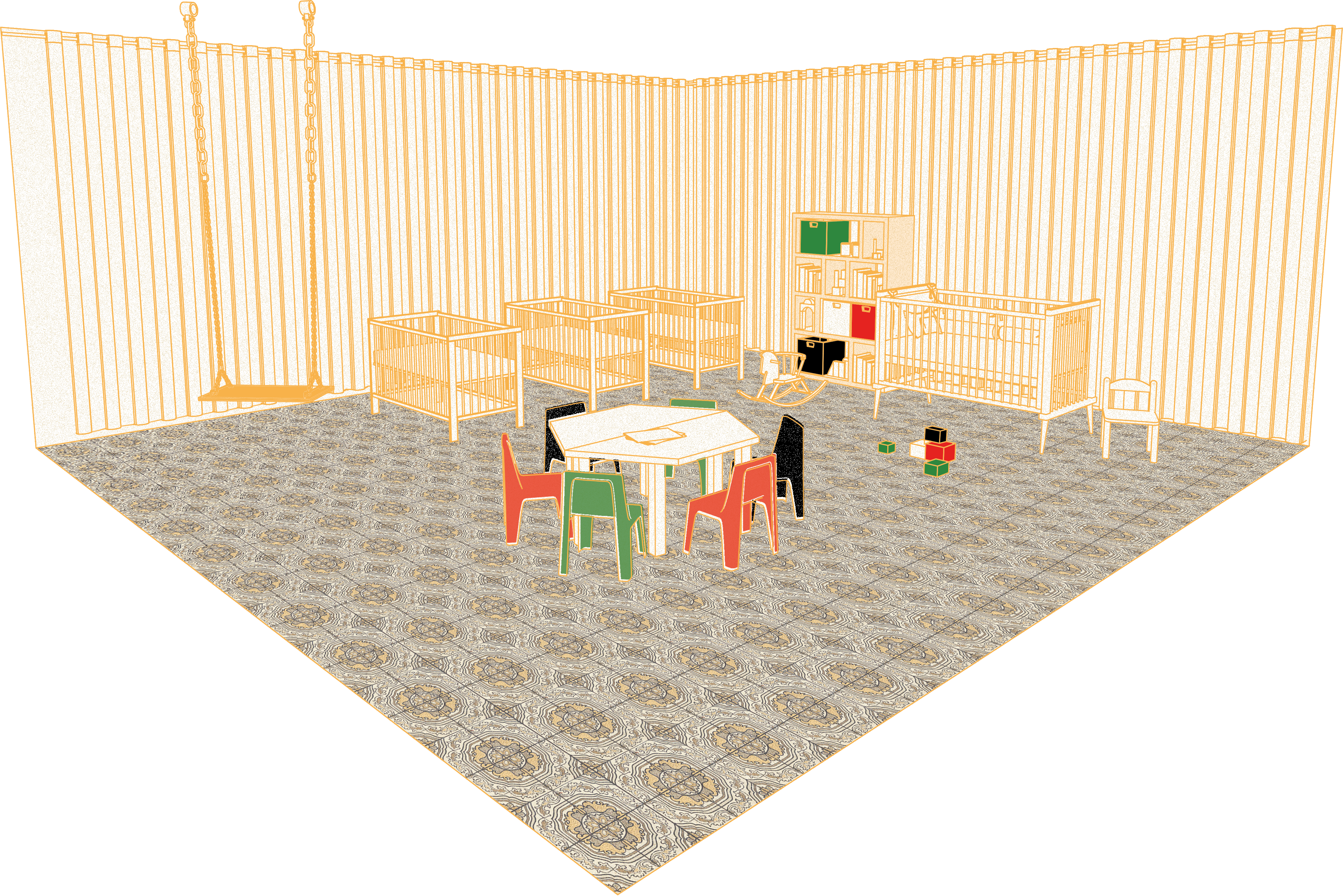

Arguably one of the most successful parts of the women’s

committees were the kindergartens. Estimates suggest 60-70 kindergartens were established

by the women’s committees between the West Bank and Gaza, with one in almost every

town and refugee camp. FPWAC [2] had 22 day care centres and over respectively. UPWC[3] had 14 kindergartens and 535 children in 1985.This includes the Ghassan

Kanafani childcare centres established by the UPWC, many of which still exist

both inside and outside Palestine to this day. An employee at the UPWC

explained in an interview how the centres were run on a not-for-profit basis,

asking only for a symbolic contribution towards the fees, with special

accommodations for poorer families and those who had family members in prison

or killed by the occupation. The idea of social care provision as part of

a revolutionary structure or moment was not new per se. In the refugee camps outside

of Palestine, informal childcare centres were provided by the Palestine Liberation

Organisation (PLO) as part of the General Union of Palestinian Women. Over fifteen

day-care facilities were established in the refugee camps outside Palestine

with the aim of developing a ‘support system’ for Palestinian female

‘self-sufficiency’ (Rubenberg 1983:45).

In part, what some of these women were arguing for stemmed from their own personal needs as both mothers and organisers. As one woman explained to me:

“Even before we started the kindergartens every time we would do a meeting we used to have a child carer come too because all the women would need to bring their children with them to the meetings and how can you do a meeting with many children? The designated carer used to take all the kids and play with them while we did our meeting. This was part of the start and it symbolised the need of the time; we would be some 20 women and most of them all have children. The idea wasn’t just that we wanted to do a kindergarten just for the sake of education our aim was to help women because if I want to talk about equality for women then I also need to talk about the services that need to be provided so that she can take up that role.”

Another leader in the women’s union movement—when asked what the nurseries meant for her own involvement—categorically answered that without them there was ‘no chance’ she would have been as active as she was. Due to the criminalisation of Palestinian political activity, many of these women’s partners were absent due to being imprisoned or underground, leaving their families in further economic and social need. In multiple interviews the women I spoke to would describe juggling their absent partners, young children, and the need to lead and organise a women’s movement at an important national juncture. She explained: “I would have had to rely on my mother. For this the presence of the nurseries is so, so important. More than you can ever imagine. Only once you have children can you recognise how important all this is. How could you ask women to be part of demonstrations with children?”

The Palestinian women’s movement did something quite extraordinary: they showed an attentiveness to the material conditions that lie at the crux of people’s everyday lives and sought to alleviate them as part of a political project, while also understanding that a political project necessarily needs to pay attention to the unequal conditions that people face and what that means for their involvement. Politically, this movement did something significant in politicising domesticity as at once an organising tool - illustrating a class-oriented organising that has been sorely missed in recent years – and as a political strategy of liberating women’s time; from the confines of the home, or the extended family. In a separate interview with a leader of the WWC and then the FPWAC she explained the main impact on women’s time: “women could make the most out of their morning time, she could study, so many went on to be able to get jobs in places like Beit Anan, Hizma, Beit Sureik, so the women could either go out to work or to go study when we opened these centres.”

In politicising domesticity and bringing it into the folds of the popular struggle sites issues such as the home, housework and women’s equality and emancipation were seen as central to liberation movements. Furthermore because of this holistic approach and understanding of the needs the necessary infrastructure as part of political movements, such as childcare, were established and seen as essential in order to provide for and mobilise women. The idea of the home as an important site of struggle is reflected in some of the writing emerging at the time. For example a poem written by Cuban feminist Milagros Gonzales that was translated into Arabic in the women’s committee magazine, Al-Kateb literary magazine from Jerusalem, and the anthology Ana Inti w al Thwara: Writings from the Third World published by Ilham Abu Ghazaleh in 1991. Feminist consciousness and women organising of this time period serves as an essential example of Arab feminist mobilisation in history.

On archiving

The presence of women in the first intifada is memorialised but the conditions which enabled such participation and presence are not. This raises important questions about how we remember, archive and memorialise significant moments in history, especially as archiving projects unfold and Palestinians increasingly look to intifada era fragments as inspiration for political futures. As I searched for the history of the women’s movement in the archive, it was only through oral history and an investigation into the history of the establishment of formal nurseries in the West Bank that I was able to access this story and then follow its traces through all the different key organisers of the time. In doing so I was then able to start constructing the story and impact of these childcare centers absent from collective memory. Every time I would discuss my research with Palestinians of my generation they would have never heard of the nurseries, even in feminist groups and movements. Moreover, in discussions of resistance economy and popular struggle an understanding or acknowledgement of this period of a holistic approach to popular struggle was absent, except among the women who relied on them and established them.

If even within these archiving and documenting projects these gendered and structural omissions are occurring, how can this enable us to think differently about archival practice? How can we think of the archiving process of moments in Palestinian revolutionary history as a process that can reflect the necessary infrastructures that were established to enable a photograph of women demonstrating in the streets of Palestine in the 1980s. It is an invitation to think through the conditions and the process of movements as part of the archiving process. It is important to think through omissions and their repercussions on both the archive and remembrance more generally. For example, what kind of information is reflected in the publications of the political parties such as Al-Hadaf (among others) and what types of activities do not get logged in them?

Oral history is an important avenue for archiving and collecting important information that gets excluded from colonial or formal archives. But it also raises the point of the formal attunement and training of researchers in such processes. To think about the conditions and processes of movements necessitates not only an anti-extractive approach to archival work (as mentioned by others on this site) but also a sensitivity to social reproductive needs. How can we think about the archiving process beyond just storing photographs of children playing in a playground in one of the women’s committee nurseries on an open access database? What details are missing, such as information about how people decided to establish the nurseries, why, in what form, and what types of dynamics and decisions needed to take place in order to support the process? What lessons can then be learnt and incorporated into archival practice, especially of revolutionary movements where such information may either be omitted, destroyed and generally hard to find? What would an archive of the infrastructure that enabled the iconic photographs of intifada look like? How then can we think of an archive of political moments and attempt to trace some of their impacts or ‘afterlives’ in other formations through time?

In many ways the history of the women’s committees and their activities, as a process, not only resulted in women having more time to work, train, learn, earn income, in an increasingly difficult economic time, but also built leaders through the organising structure itself. When these nurseries were established their importance lay beyond the material provisions they provided: they were also a space that thought creatively about the curriculum, and many figures who later went on to pioneer in the field of early childcare in Palestine in the 1990s were involved in the women’s committees nurseries. The women’s committees in the first intifada saw women’s time as an integral part of the resistance economy. This is not meant to be a call for a romanticised past; childcare in Palestine today is expensive, exploitative for workers, includes notoriously bad conditions and is neoliberalised. Rather it is an invitation to think through social reproduction patterns and who picks up the burden. Early childcare is no longer a pioneering element in Palestinian society as it used to be, but the lessons on how to think through what a gendered resistance economy could look like beyond food, health or small scale production, and to pay attention to how class and gender play into people’s material day to day lives beyond slogans or statements. This story is an invitation to think of what an archive of political processes and an archive of possibility might look like. It asks why some stories are forgotten and then become little known at our current political and historical conjuncture - why?

In part, what some of these women were arguing for stemmed from their own personal needs as both mothers and organisers. As one woman explained to me:

“Even before we started the kindergartens every time we would do a meeting we used to have a child carer come too because all the women would need to bring their children with them to the meetings and how can you do a meeting with many children? The designated carer used to take all the kids and play with them while we did our meeting. This was part of the start and it symbolised the need of the time; we would be some 20 women and most of them all have children. The idea wasn’t just that we wanted to do a kindergarten just for the sake of education our aim was to help women because if I want to talk about equality for women then I also need to talk about the services that need to be provided so that she can take up that role.”

Another leader in the women’s union movement—when asked what the nurseries meant for her own involvement—categorically answered that without them there was ‘no chance’ she would have been as active as she was. Due to the criminalisation of Palestinian political activity, many of these women’s partners were absent due to being imprisoned or underground, leaving their families in further economic and social need. In multiple interviews the women I spoke to would describe juggling their absent partners, young children, and the need to lead and organise a women’s movement at an important national juncture. She explained: “I would have had to rely on my mother. For this the presence of the nurseries is so, so important. More than you can ever imagine. Only once you have children can you recognise how important all this is. How could you ask women to be part of demonstrations with children?”

The Palestinian women’s movement did something quite extraordinary: they showed an attentiveness to the material conditions that lie at the crux of people’s everyday lives and sought to alleviate them as part of a political project, while also understanding that a political project necessarily needs to pay attention to the unequal conditions that people face and what that means for their involvement. Politically, this movement did something significant in politicising domesticity as at once an organising tool - illustrating a class-oriented organising that has been sorely missed in recent years – and as a political strategy of liberating women’s time; from the confines of the home, or the extended family. In a separate interview with a leader of the WWC and then the FPWAC she explained the main impact on women’s time: “women could make the most out of their morning time, she could study, so many went on to be able to get jobs in places like Beit Anan, Hizma, Beit Sureik, so the women could either go out to work or to go study when we opened these centres.”

In politicising domesticity and bringing it into the folds of the popular struggle sites issues such as the home, housework and women’s equality and emancipation were seen as central to liberation movements. Furthermore because of this holistic approach and understanding of the needs the necessary infrastructure as part of political movements, such as childcare, were established and seen as essential in order to provide for and mobilise women. The idea of the home as an important site of struggle is reflected in some of the writing emerging at the time. For example a poem written by Cuban feminist Milagros Gonzales that was translated into Arabic in the women’s committee magazine, Al-Kateb literary magazine from Jerusalem, and the anthology Ana Inti w al Thwara: Writings from the Third World published by Ilham Abu Ghazaleh in 1991. Feminist consciousness and women organising of this time period serves as an essential example of Arab feminist mobilisation in history.

On archiving

The presence of women in the first intifada is memorialised but the conditions which enabled such participation and presence are not. This raises important questions about how we remember, archive and memorialise significant moments in history, especially as archiving projects unfold and Palestinians increasingly look to intifada era fragments as inspiration for political futures. As I searched for the history of the women’s movement in the archive, it was only through oral history and an investigation into the history of the establishment of formal nurseries in the West Bank that I was able to access this story and then follow its traces through all the different key organisers of the time. In doing so I was then able to start constructing the story and impact of these childcare centers absent from collective memory. Every time I would discuss my research with Palestinians of my generation they would have never heard of the nurseries, even in feminist groups and movements. Moreover, in discussions of resistance economy and popular struggle an understanding or acknowledgement of this period of a holistic approach to popular struggle was absent, except among the women who relied on them and established them.

If even within these archiving and documenting projects these gendered and structural omissions are occurring, how can this enable us to think differently about archival practice? How can we think of the archiving process of moments in Palestinian revolutionary history as a process that can reflect the necessary infrastructures that were established to enable a photograph of women demonstrating in the streets of Palestine in the 1980s. It is an invitation to think through the conditions and the process of movements as part of the archiving process. It is important to think through omissions and their repercussions on both the archive and remembrance more generally. For example, what kind of information is reflected in the publications of the political parties such as Al-Hadaf (among others) and what types of activities do not get logged in them?

Oral history is an important avenue for archiving and collecting important information that gets excluded from colonial or formal archives. But it also raises the point of the formal attunement and training of researchers in such processes. To think about the conditions and processes of movements necessitates not only an anti-extractive approach to archival work (as mentioned by others on this site) but also a sensitivity to social reproductive needs. How can we think about the archiving process beyond just storing photographs of children playing in a playground in one of the women’s committee nurseries on an open access database? What details are missing, such as information about how people decided to establish the nurseries, why, in what form, and what types of dynamics and decisions needed to take place in order to support the process? What lessons can then be learnt and incorporated into archival practice, especially of revolutionary movements where such information may either be omitted, destroyed and generally hard to find? What would an archive of the infrastructure that enabled the iconic photographs of intifada look like? How then can we think of an archive of political moments and attempt to trace some of their impacts or ‘afterlives’ in other formations through time?

In many ways the history of the women’s committees and their activities, as a process, not only resulted in women having more time to work, train, learn, earn income, in an increasingly difficult economic time, but also built leaders through the organising structure itself. When these nurseries were established their importance lay beyond the material provisions they provided: they were also a space that thought creatively about the curriculum, and many figures who later went on to pioneer in the field of early childcare in Palestine in the 1990s were involved in the women’s committees nurseries. The women’s committees in the first intifada saw women’s time as an integral part of the resistance economy. This is not meant to be a call for a romanticised past; childcare in Palestine today is expensive, exploitative for workers, includes notoriously bad conditions and is neoliberalised. Rather it is an invitation to think through social reproduction patterns and who picks up the burden. Early childcare is no longer a pioneering element in Palestinian society as it used to be, but the lessons on how to think through what a gendered resistance economy could look like beyond food, health or small scale production, and to pay attention to how class and gender play into people’s material day to day lives beyond slogans or statements. This story is an invitation to think of what an archive of political processes and an archive of possibility might look like. It asks why some stories are forgotten and then become little known at our current political and historical conjuncture - why?

Lucy Garbett

Lucy Garbett is a researcher at the London School of Economics and Social Science based in Jerusalem.

︎︎︎ ︎