Pedro Monaville

The Business of

Revolutionary

Archives

The Congo became independent on June 30, 1960. Less than a week later, soldiers around the country mutinied. Taking advantage of these chaotic circumstances, neocolonial forces encouraged secessions in two mineral-rich provinces, and cold war interveners conspired to destabilize the central government. The Congo crisis, as it was called, culminated with the assassination of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in January 1961. The crisis put the country at the center of global attention. Around the world, people felt moved and enraged by the Congolese tragedy. The fate of Lumumba led to countless demonstrations and protests, from New York to Cairo and Delhi. While this is less well-known, in the Congo itself, the Crisis and Lumumba’s assassination also led to significant mobilizations. This notably resulted in the birth of a powerful student movement that became one of the most significant forces in the Congolese nationalist camp in the 1960s.

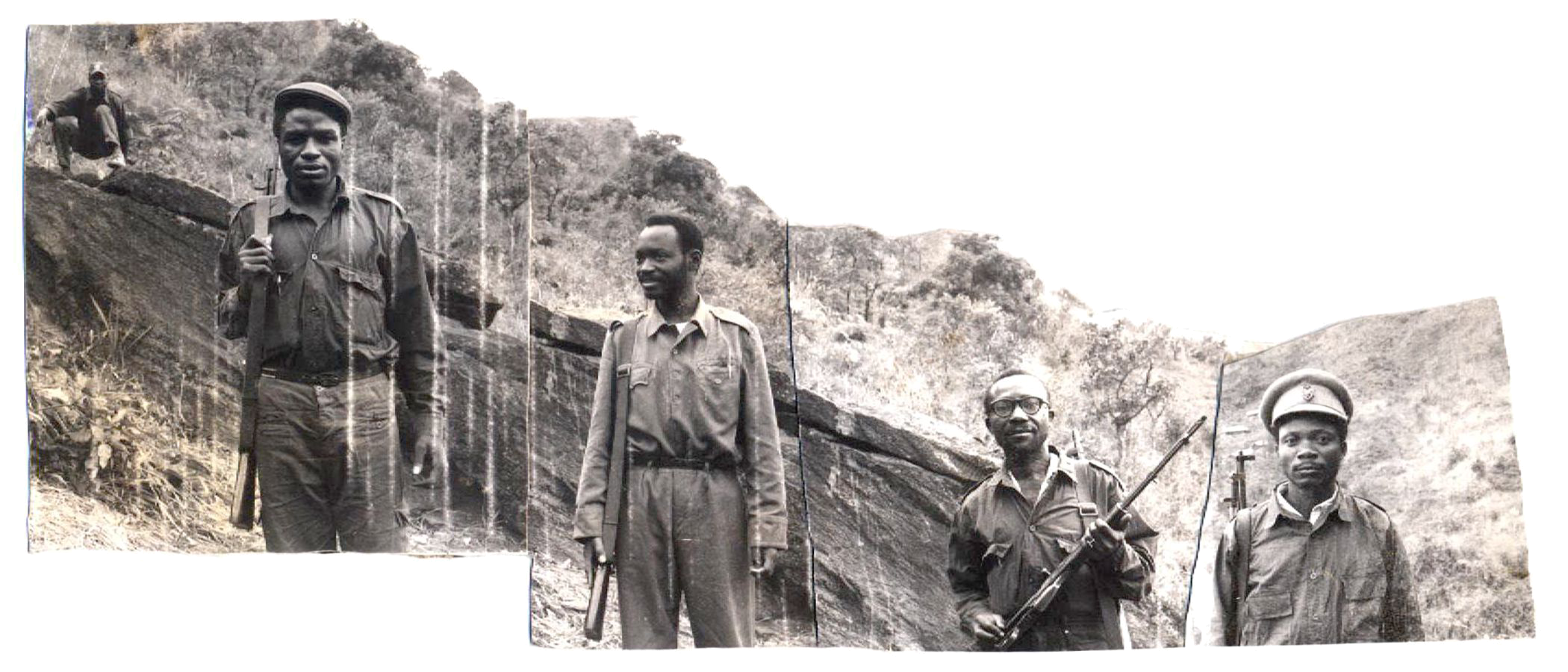

Students wanted to follow in Lumumba’s path. They defended Congolese unity and Pan-Africanism. In 1963 and 1964, many of them joined the armed struggles waged by former Lumumba sympathizers in different parts of the country. After General Mobutu captured power and established the foundations of his dictatorial rule, student unions were the only organization daring to openly protest the new regime. Violent repression ensued: a massacre in the streets of Kinshasa, the forced enrollment of 2000 students in the military, many activists sent to jail, and the de facto end of student mobilizations on Congolese campuses.

By the early 1970s, Mobutu had defeated the student movement. Yet, many former activists remained committed to the visions of the 1960s. A large number soldiered through the decades of Mobutu’s rule from distant exiles. When Laurent-Désiré Kabila, himself a former Lumumbist organizer, took power in 1997 after an armed rebellion that overthrew Mobutu, he surrounded himself with former members of the student movement. Left Lumumbist ideals were again at the forefront. But after Kabila was assassinated, forty years, nearly to the day, after Lumumba, he was replaced by his son Joseph—a young man who did not feel committed to the political horizon of the post-independence era in the same way his father had.

In 2006, I began a long-term research project on the history of Congolese student activism at the time the global 1960s. Several of my interlocutors were former student leaders who had occupied positions of responsibilities around the old Kabila but faced significantly reduced access to power and influence under his son’s rule. One of these figures was a Marxist politician who had entered the student movement at the very beginning of the 1970s, had been involved in anti-Mobutist armed insurrections later in that decade, and served as a minister in Kabila’s first government in 1997. When I first met him ten years later, he was the leader of a small political organization trying to resist the rapid erosion of left positions in the post-Laurent-Désiré Kabila era. One day, as I paid him a visit at his party’s offices, he recommended that I connect with another former student leader, and he asked one of his young aides to walk with me to this person’s house. On our way there, the aide and I talked about this and that. At one point, he told me something I found arresting. “I am in the business of politics,” he said. “It does not pay much at the moment, but there might be opportunities in the future.” Then, with candid curiosity, he inquired: “What about the business of history?”

This young man’s entrepreneurial vision about politics suggested a striking generational disconnect. It symbolized, I felt, the difficulty of militant histories to register and left lexicons to roll over after decades of ruination, corruption, and general pauperization under Mobutu. In a context in which most Congolese had to deploy incredible levels of resourcefulness to make ends meet on an everyday basis, transactional relations pervaded all sectors of society, even the premises of a political party that claimed the legacy of a decades-long revolutionary struggle.

Over the following years, as I continued my research, I encountered more signs of this disconnect. The many former student activists of the 1960s that I met enthusiastically welcomed my interest in the history of their movement. They were glad to reminisce about their younger years as students and activists – but they also often complained that this history had been unfairly forgotten.

I often asked my interlocutors if they had kept photographs, diaries, letters, or pamphlets from their student years. Very rarely was it the case. Instead of personal archives, what I collected were stories about absences and erasures of material traces from the student movement. Under the dictatorship, a great number of people felt compelled to get rid of documents that could have been used against them. Personal belongings were left behind, lost, or damaged during moves or fires. Family members converted to Pentecostalist churches and pushed their relatives to destroy political memorabilia that they associated with witchcraft. And there were the lootings and the wars that devasted Kinshasa in the 1990s and affected public and private archives alike.

One reviewer of the book that came out of my research on the history of the student movement suggested that the work could be read as an elegy. The reviewer had in mind the book’s last chapters, where I center on the bloody repression of student discontent, the lives that were lost and the dreams that were crushed. Reflecting on my conversations with former student activists, I believe that the elegiac stance I captured was also informed by my interlocutors’ longing for their lost relics and keepsakes. The absence of material traces resulted in feelings of dispossession that were affective and political. It shaped the stories that could be shared.

Despite the richness of oral sources, some aspects of the student imagination and activism had faded away – ideas that were more difficult to translate in the present, made less sense in relation to the memory work that former students were willing to carry, or related to tensions, contradictions, wounds, and complexities that some chose to forget. Clearly too, archival lacunas in Kinshasa were not unrelated to the crisis of the left in the 2000s and the difficulties of an older generation of activists to be heard and understood by the youth.

Research fellowships and an EU passport allowed me to get around the archival gap in Kinshasa. Conducting research in archival centers in the Global North, I worked with a great number of collections that proved key for my research. Various foreign governments, political parties, and academic institutions kept an eye on Congolese students in the 1960s. Reading surveillance reports and dispatches—from the US, French, and Belgian embassies in Kinshasa; the United States National Student Association; the AFL-CIO; the International Union of Socialist Youth; the Belgian Communist Party; East and West German labor unions; the Albanian government; and several other entities—opened to critical insights.

Letters sent by Congolese to foreign organizations and activists proved even more fascinating. Students in the context of the Congo crisis and of the global 1960s looked at themselves as outward-facing mediators who could translate Congolese realities to foreign interlocutors on the one hand, and connecting their country to distant political horizons, struggles and currents of ideas on the other. Their internationalist appetite was strongly reflected in the letters I found. They talked of their dreams and visions of the world, relating to a variety of socialist projects and outlining the subterranean connections they perceived between the situation of the Congo and multiple other struggles from the anti-imperialist war in Vietnam to the Black Power movement in North American cities.

Students wanted to follow in Lumumba’s path. They defended Congolese unity and Pan-Africanism. In 1963 and 1964, many of them joined the armed struggles waged by former Lumumba sympathizers in different parts of the country. After General Mobutu captured power and established the foundations of his dictatorial rule, student unions were the only organization daring to openly protest the new regime. Violent repression ensued: a massacre in the streets of Kinshasa, the forced enrollment of 2000 students in the military, many activists sent to jail, and the de facto end of student mobilizations on Congolese campuses.

By the early 1970s, Mobutu had defeated the student movement. Yet, many former activists remained committed to the visions of the 1960s. A large number soldiered through the decades of Mobutu’s rule from distant exiles. When Laurent-Désiré Kabila, himself a former Lumumbist organizer, took power in 1997 after an armed rebellion that overthrew Mobutu, he surrounded himself with former members of the student movement. Left Lumumbist ideals were again at the forefront. But after Kabila was assassinated, forty years, nearly to the day, after Lumumba, he was replaced by his son Joseph—a young man who did not feel committed to the political horizon of the post-independence era in the same way his father had.

In 2006, I began a long-term research project on the history of Congolese student activism at the time the global 1960s. Several of my interlocutors were former student leaders who had occupied positions of responsibilities around the old Kabila but faced significantly reduced access to power and influence under his son’s rule. One of these figures was a Marxist politician who had entered the student movement at the very beginning of the 1970s, had been involved in anti-Mobutist armed insurrections later in that decade, and served as a minister in Kabila’s first government in 1997. When I first met him ten years later, he was the leader of a small political organization trying to resist the rapid erosion of left positions in the post-Laurent-Désiré Kabila era. One day, as I paid him a visit at his party’s offices, he recommended that I connect with another former student leader, and he asked one of his young aides to walk with me to this person’s house. On our way there, the aide and I talked about this and that. At one point, he told me something I found arresting. “I am in the business of politics,” he said. “It does not pay much at the moment, but there might be opportunities in the future.” Then, with candid curiosity, he inquired: “What about the business of history?”

This young man’s entrepreneurial vision about politics suggested a striking generational disconnect. It symbolized, I felt, the difficulty of militant histories to register and left lexicons to roll over after decades of ruination, corruption, and general pauperization under Mobutu. In a context in which most Congolese had to deploy incredible levels of resourcefulness to make ends meet on an everyday basis, transactional relations pervaded all sectors of society, even the premises of a political party that claimed the legacy of a decades-long revolutionary struggle.

Over the following years, as I continued my research, I encountered more signs of this disconnect. The many former student activists of the 1960s that I met enthusiastically welcomed my interest in the history of their movement. They were glad to reminisce about their younger years as students and activists – but they also often complained that this history had been unfairly forgotten.

I often asked my interlocutors if they had kept photographs, diaries, letters, or pamphlets from their student years. Very rarely was it the case. Instead of personal archives, what I collected were stories about absences and erasures of material traces from the student movement. Under the dictatorship, a great number of people felt compelled to get rid of documents that could have been used against them. Personal belongings were left behind, lost, or damaged during moves or fires. Family members converted to Pentecostalist churches and pushed their relatives to destroy political memorabilia that they associated with witchcraft. And there were the lootings and the wars that devasted Kinshasa in the 1990s and affected public and private archives alike.

One reviewer of the book that came out of my research on the history of the student movement suggested that the work could be read as an elegy. The reviewer had in mind the book’s last chapters, where I center on the bloody repression of student discontent, the lives that were lost and the dreams that were crushed. Reflecting on my conversations with former student activists, I believe that the elegiac stance I captured was also informed by my interlocutors’ longing for their lost relics and keepsakes. The absence of material traces resulted in feelings of dispossession that were affective and political. It shaped the stories that could be shared.

Despite the richness of oral sources, some aspects of the student imagination and activism had faded away – ideas that were more difficult to translate in the present, made less sense in relation to the memory work that former students were willing to carry, or related to tensions, contradictions, wounds, and complexities that some chose to forget. Clearly too, archival lacunas in Kinshasa were not unrelated to the crisis of the left in the 2000s and the difficulties of an older generation of activists to be heard and understood by the youth.

Research fellowships and an EU passport allowed me to get around the archival gap in Kinshasa. Conducting research in archival centers in the Global North, I worked with a great number of collections that proved key for my research. Various foreign governments, political parties, and academic institutions kept an eye on Congolese students in the 1960s. Reading surveillance reports and dispatches—from the US, French, and Belgian embassies in Kinshasa; the United States National Student Association; the AFL-CIO; the International Union of Socialist Youth; the Belgian Communist Party; East and West German labor unions; the Albanian government; and several other entities—opened to critical insights.

Letters sent by Congolese to foreign organizations and activists proved even more fascinating. Students in the context of the Congo crisis and of the global 1960s looked at themselves as outward-facing mediators who could translate Congolese realities to foreign interlocutors on the one hand, and connecting their country to distant political horizons, struggles and currents of ideas on the other. Their internationalist appetite was strongly reflected in the letters I found. They talked of their dreams and visions of the world, relating to a variety of socialist projects and outlining the subterranean connections they perceived between the situation of the Congo and multiple other struggles from the anti-imperialist war in Vietnam to the Black Power movement in North American cities.

For all their incredible usefulness, the sources I found in archival centers in the Global North presented some limitations. Reports by foreigners on Congolese students often involved biases and misunderstandings, while the letters Congolese wrote to outsiders were ultimately shaped the adjustments required in communications with people who stood outside of their movement and lived realities.

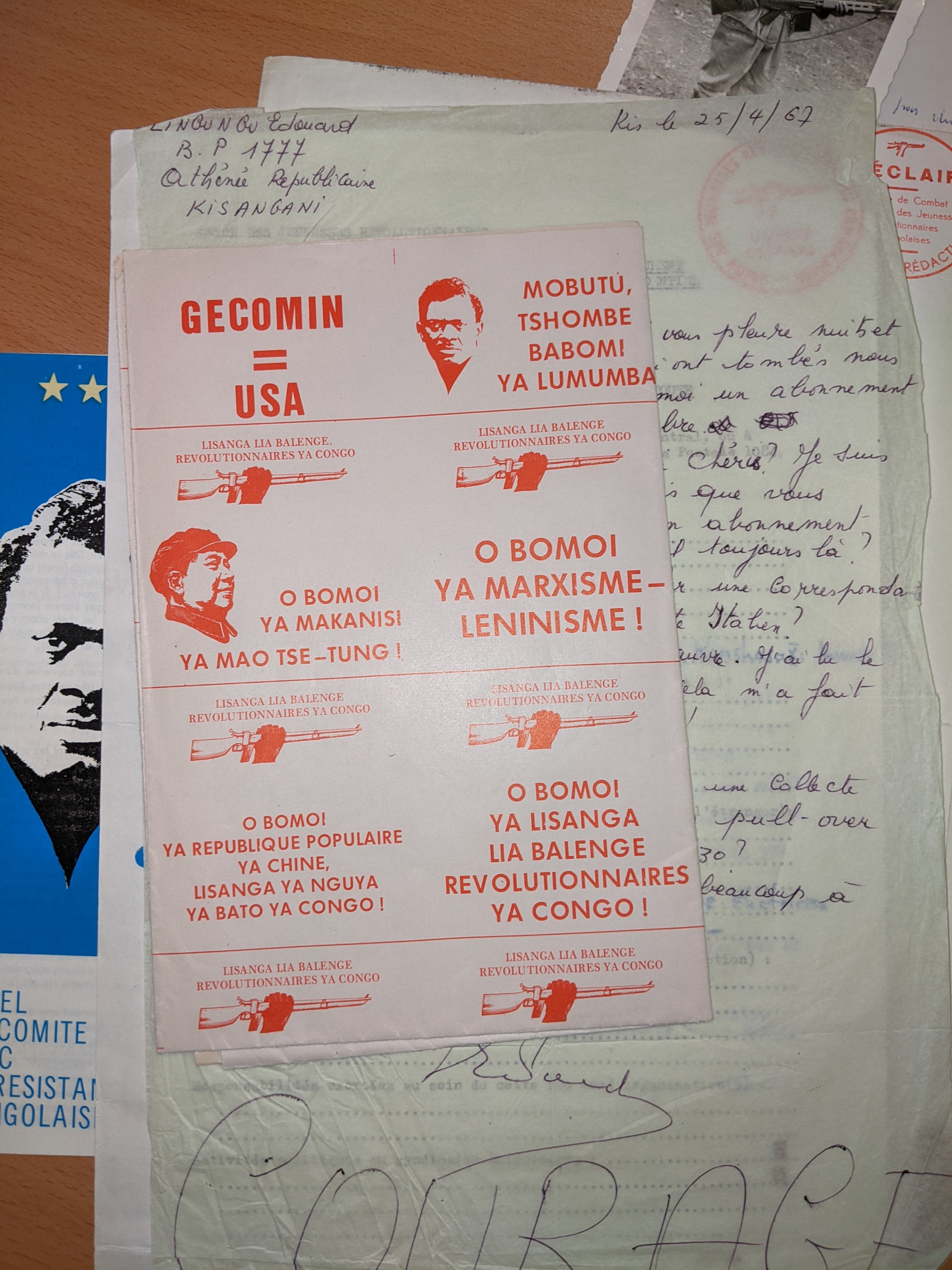

Ultimately, though, one collection offered a corrective to these shortcomings. It was the papers of the Congolese Revolutionary Youth Union (UJRC), a small Maoist organization that Congolese students in Europe launched in the mid-1960s as a strategic linchpin connecting students at home and abroad with the Lumumbist militants active in armed struggles in Eastern Congo and their supporters in Havana, Cairo, Berlin, and Beijing.

Ultimately, though, one collection offered a corrective to these shortcomings. It was the papers of the Congolese Revolutionary Youth Union (UJRC), a small Maoist organization that Congolese students in Europe launched in the mid-1960s as a strategic linchpin connecting students at home and abroad with the Lumumbist militants active in armed struggles in Eastern Congo and their supporters in Havana, Cairo, Berlin, and Beijing.

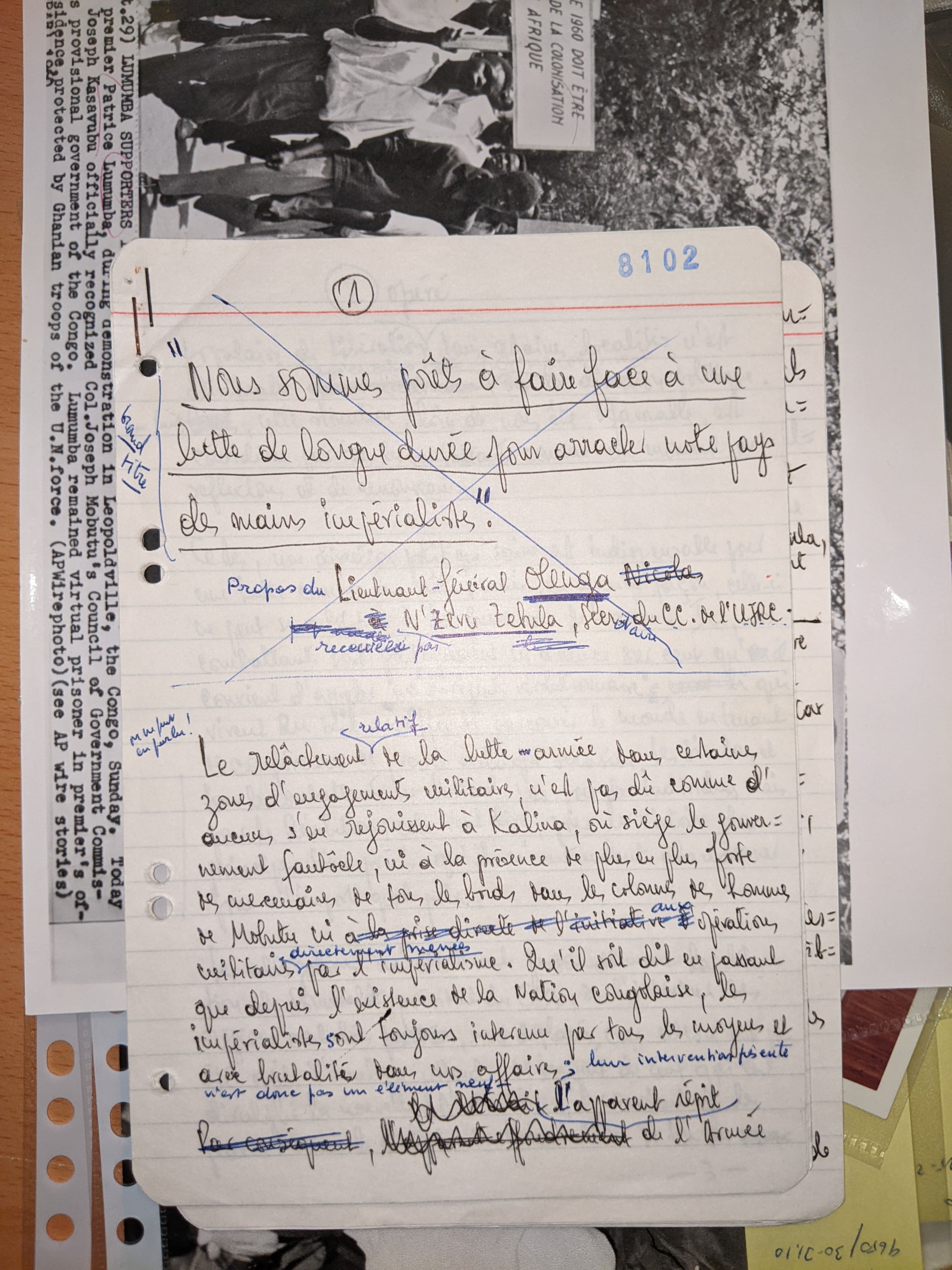

The UJRC published L’éclair, a militant magazine that the group mailed to thousands of readers across Europe, Africa, and Asia. The archives I accessed included numerous letters from these readers, as well countless documents related to the production of the magazine and unpublished pamphlets in various draft stages. There were also photographs, letters exchanges among the group’s leaders, and minutes of their meetings. These documents offered a unique take on the strategic choice the group made and on the ideological debates and sources of friction that led to its dismemberment in 1967.

The UJRC papers were not housed in a research center. Instead, they sat in a garage in the suburb of a Belgian provincial center. I came to know of the collection, after noticing highly relevant materials for my work on the website of an online marketplace for rare books and collectibles. The vendor – I later found out – was a Belgian man who had been part of the UJRC in the 1960s, as the only non-Congolese member of the leadership. He had served as the editorial secretary of L’éclair and the de facto archivist for the organization. In parallel with his involvement with Congolese students, he also wrote for the newspaper of the Maoist split of the Belgian communist party. In the 1970s, he became active in gay community organizations in Brussels. Later, he spent years living in East Asia. All along, he accumulated vast quantities of materials related to his diverse activities, and in the 2000s, he decided to sell the documents that he had kept during his earlier life as a political activist. He reached out to multiple research centers and archives in Belgium and abroad – but none proved able or willing to acquire his collections on Congo. Used books websites offered an alternative to monetize his old revolutionary papers. On the UJRC and Congolese left alone, I found several hundred individual items (photographs, letters, extremely rare militant publications, pamphlets, etc.) that he had listed online, each with very detailed information about the nature of the document and relevant contexts and people associated with it.

The scale and richness of the collection amazed me once I was able to fully grasp it. But it also worried me that it could disappear, auctioned off piecemeal on the internet. And I was flabbergasted at the high cost at which each item was going for. Ultimately, I was able to negotiate access with the vendor. I used a research grant to purchase several folders of documents, and he allowed me to make copies of the rest of his collection for research purposes.

Reading the UJRC papers created a feeling of closeness with the past that did not exist in the same way in interviews with members of the group. This was invaluable for me as a historian. At the same time, the mercantile afterlife of the collection painfully echoed the feelings of dispossession of the former activists I met in Kinshasa. The documents proved transformative in the writing of my book. The work itself – supported and eagerly awaited by my many Congolese interlocutors – functioned as a form of restitution. But clearly, there was more to be done with this salvaged archive. One opportunity to do so presented itself when the Congolese visual artist Sammy Baloji asked me to collaborate with him on a project about the Congo in the cold war. Our work together is ongoing, but it has already led to the production of two installations – one first shown at the Sharjah Art Biennale in 2023, and the other at Goldsmiths Center for Contemporary Art in 2024.

The UJRC papers were not housed in a research center. Instead, they sat in a garage in the suburb of a Belgian provincial center. I came to know of the collection, after noticing highly relevant materials for my work on the website of an online marketplace for rare books and collectibles. The vendor – I later found out – was a Belgian man who had been part of the UJRC in the 1960s, as the only non-Congolese member of the leadership. He had served as the editorial secretary of L’éclair and the de facto archivist for the organization. In parallel with his involvement with Congolese students, he also wrote for the newspaper of the Maoist split of the Belgian communist party. In the 1970s, he became active in gay community organizations in Brussels. Later, he spent years living in East Asia. All along, he accumulated vast quantities of materials related to his diverse activities, and in the 2000s, he decided to sell the documents that he had kept during his earlier life as a political activist. He reached out to multiple research centers and archives in Belgium and abroad – but none proved able or willing to acquire his collections on Congo. Used books websites offered an alternative to monetize his old revolutionary papers. On the UJRC and Congolese left alone, I found several hundred individual items (photographs, letters, extremely rare militant publications, pamphlets, etc.) that he had listed online, each with very detailed information about the nature of the document and relevant contexts and people associated with it.

The scale and richness of the collection amazed me once I was able to fully grasp it. But it also worried me that it could disappear, auctioned off piecemeal on the internet. And I was flabbergasted at the high cost at which each item was going for. Ultimately, I was able to negotiate access with the vendor. I used a research grant to purchase several folders of documents, and he allowed me to make copies of the rest of his collection for research purposes.

Reading the UJRC papers created a feeling of closeness with the past that did not exist in the same way in interviews with members of the group. This was invaluable for me as a historian. At the same time, the mercantile afterlife of the collection painfully echoed the feelings of dispossession of the former activists I met in Kinshasa. The documents proved transformative in the writing of my book. The work itself – supported and eagerly awaited by my many Congolese interlocutors – functioned as a form of restitution. But clearly, there was more to be done with this salvaged archive. One opportunity to do so presented itself when the Congolese visual artist Sammy Baloji asked me to collaborate with him on a project about the Congo in the cold war. Our work together is ongoing, but it has already led to the production of two installations – one first shown at the Sharjah Art Biennale in 2023, and the other at Goldsmiths Center for Contemporary Art in 2024.

For these two pieces, “Tshinkolobwe’s Abstractions” and “Triga Mark III,” Baloji created a series of prints that meant to recall the centrality of Congolese minerals in the atomic era. In the two installations, Baloji’s images were exhibited together with selections from the UJRC papers. The dialogue between the archives and the images suggests various modalities of Congolese immanence to the world of the global cold war – as a source of extractivism, but also as a site of resistance and a significant node in the age of Tricontinentalism. Baloji’s artistic intervention suggests possibilities of historical redress, and hopefully it brings a more meaningful coda to the ambivalent history of a key set of revolutionary papers.

Pedro Monaville

Pedro Monaville is a historian of modern Africa. His research focuses on colonial and postcolonial Congo, revolutionary movements, political subjectivities, knowledge production, popular culture, memory work, and the connections between visual arts and history. His first book, Students of the World: Global 1968 and Decolonization in the Congo was published by Duke University Press in 2022. The book focuses on student activism in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1960s and 1970s. Through their activism and intellectual work, students introduced and mediated new ideas about culture, politics, and the world. In this book, Monaville shows how students reimagined the Congo as a decolonized polity by connecting their country to global discussions about revolution, authenticity, and equality.

Professor Monaville is currently working on three new research projects: a history of the decolonization of the Catholic church in the Congo, a study of knowledge production in postcolonial Africa centered around the trajectory of the late Congolese scholar Tshikala Kayembe Biaya, and a book about Belgian colonialism in the interwar years. He is also the co-editor of two forthcoming volumes: a collection of essays around the work of the Bandes-Dessinées artist Mfumu'Eto and an English translation of Yoka Mudaba Lye's Kinshasa, signes de vie.

︎ ︎

Pedro Monaville is a historian of modern Africa. His research focuses on colonial and postcolonial Congo, revolutionary movements, political subjectivities, knowledge production, popular culture, memory work, and the connections between visual arts and history. His first book, Students of the World: Global 1968 and Decolonization in the Congo was published by Duke University Press in 2022. The book focuses on student activism in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1960s and 1970s. Through their activism and intellectual work, students introduced and mediated new ideas about culture, politics, and the world. In this book, Monaville shows how students reimagined the Congo as a decolonized polity by connecting their country to global discussions about revolution, authenticity, and equality.

Professor Monaville is currently working on three new research projects: a history of the decolonization of the Catholic church in the Congo, a study of knowledge production in postcolonial Africa centered around the trajectory of the late Congolese scholar Tshikala Kayembe Biaya, and a book about Belgian colonialism in the interwar years. He is also the co-editor of two forthcoming volumes: a collection of essays around the work of the Bandes-Dessinées artist Mfumu'Eto and an English translation of Yoka Mudaba Lye's Kinshasa, signes de vie.

︎ ︎