Yasmine Kherfi

The Dust Does Not

Simply Settle:

Temporalities of Violence, Kinetic Knowledge & Theatre Production as Archive

Feeling contemplative with the city, I leave the house earlier than planned, opting for an hour-long walk across the streets of Berlin to catch the 8pm showtime of ‘A summary of everything that was’ at the theatre with my colleagues. My walk is straightforward. I've checked and decided on a route via Google Maps. I cross the landmark television tower on Alexanderplatz, the bridge over the Spree river, and stroll through Museum Island -a UNESCO-world heritage site that boasts cultural institutions of high stature, dedicated to the memorialization of the past. The streets are brimming neoclassical architecture, landmark sculptures, and buildings that house Greek, Roman, and Egyptian artefacts.

Around the corner from the state opera house, is the Maxim Gorki theatre. The space feels inviting and instinctively reads like an outlier in this mosaic of high culture. The play in question is a stage adaptation of a collection of Arabic short stories by Syrian writer Rasha Abbas, directed by Sebastian Nübling and the Ensemble. It seems fittingly housed here – a public arts space named after the prominent socialist writer and known for centering refugees and immigrants as cultural producers and cast members. The young, multi-lingual actors featured on this occasion are Syrian and Palestinian.

Abbas’ short stories are transformed from text to performance through a minimalist design set, though the performance is anything but that. There’s an infliction of excess, as the audience is quickly thrust into a world of visual and sonic stimulation, with the script projected on a screen throughout the play -alternating between Arabic, English, and German translations when relevant.

Through its very formulation, ‘A summary of everything that was,’ presents itself as a poetic expression of a historical record. It feels like a compressed, time-lapsed account of the characters’ lives; a panoramic yet profound rendition of the groundlessness that they experience between war and exile. The performance chronicles aspects of their everyday lives, particularly the struggles of exile in Germany, while revealing how they reckon with spectacular violence from a protracted war in Syria. The production draws attention to how such predicaments leave them grievously floating across time and space. In some ways, they cannot move beyond this. The dust simply cannot settle when the storm is yet in motion.

In this piece, I reflect on how one can situate a theatre performance within an ecosystem of initiatives that continue to archive insurgent histories and ongoing struggles from Southwest Asia and North Africa. I pause here on two aspects that stand out to me throughout the performance as well: the notion of ‘the body as archive,’ as well as how the play archives a specific conception of time.

Around the corner from the state opera house, is the Maxim Gorki theatre. The space feels inviting and instinctively reads like an outlier in this mosaic of high culture. The play in question is a stage adaptation of a collection of Arabic short stories by Syrian writer Rasha Abbas, directed by Sebastian Nübling and the Ensemble. It seems fittingly housed here – a public arts space named after the prominent socialist writer and known for centering refugees and immigrants as cultural producers and cast members. The young, multi-lingual actors featured on this occasion are Syrian and Palestinian.

Abbas’ short stories are transformed from text to performance through a minimalist design set, though the performance is anything but that. There’s an infliction of excess, as the audience is quickly thrust into a world of visual and sonic stimulation, with the script projected on a screen throughout the play -alternating between Arabic, English, and German translations when relevant.

Through its very formulation, ‘A summary of everything that was,’ presents itself as a poetic expression of a historical record. It feels like a compressed, time-lapsed account of the characters’ lives; a panoramic yet profound rendition of the groundlessness that they experience between war and exile. The performance chronicles aspects of their everyday lives, particularly the struggles of exile in Germany, while revealing how they reckon with spectacular violence from a protracted war in Syria. The production draws attention to how such predicaments leave them grievously floating across time and space. In some ways, they cannot move beyond this. The dust simply cannot settle when the storm is yet in motion.

In this piece, I reflect on how one can situate a theatre performance within an ecosystem of initiatives that continue to archive insurgent histories and ongoing struggles from Southwest Asia and North Africa. I pause here on two aspects that stand out to me throughout the performance as well: the notion of ‘the body as archive,’ as well as how the play archives a specific conception of time.

Temporalities of Violence

‘A summary of everything that was’ traces the characters’ experience and relationship to time, through a disorienting, non-linear performance. The spectator sits close to the human mind through this mode of narration. I feel as though I’ve crawled into someone’s brain, vividly bearing witness to their interiority; their racing thoughts that scream on the inside, while the acoustics of their skin render their reflections at times mute from the outside. What does this sort of theatrical immersion invite? This psychological proximity reminds of Saidiya Hartman’s practice of critical fabulation, in that it offers a mode of close narration that challenges a common disciplinary tendency to sever the author and the personal from the process of historical writing and expression at large. In this case, the line between character and narrator is blurred. The actors embody both roles, which provides an opening ripe with possibilities for crafting intimate stories about ‘everything that was.’ As I follow their speech and movements, however, I feel too close to them, and it’s not always easy to distinguish their inner voice from what they outwardly express. Their monologues at times feel crafted in surrealist, automatist fashion -as though they are not in control over their diction.

The spectator is dizzy, or at least I am - oscillating between deep dives into what feels like the characters’ inner worlds, and instances of external release, which show up as eruptions of fragmented thoughts.

The production archives an alternative relationship to time by challenging story-telling conventions; it becomes quickly clear that it doesn’t have an expected sequence of events, the narrative arc is absent, the characters are not clearly charted, and the places from which they speak are not always obvious. How can one then trace the time of a story – an ambitious synthesis of ‘everything’ as the title suggests, in the absence of a narrative thread? The play unsettles a desire for mastery – as Julietta Singh would describe. In this case, mastery over time; the ability to organize, classify, and chart a time-line. With this common inclination for control comes a disposition towards linearity - the comforting logic used to make sense of time.

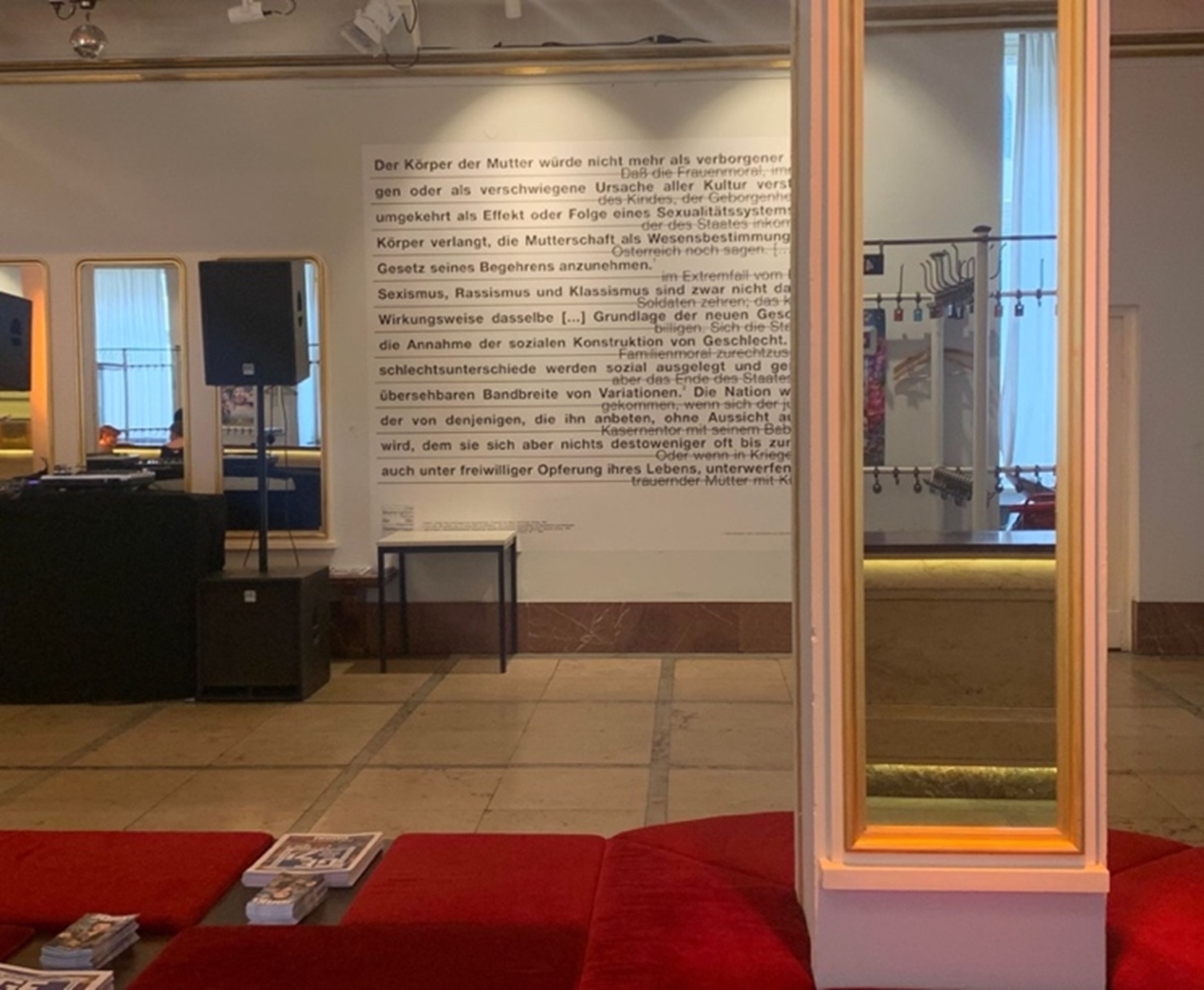

Instead, the spectator is forced into a freefall alongside the characters who are experiencing it. Here, there is no series of events that can be neatly presented to factually recount ‘a summary of everything.’ And this doesn’t seem to be the point. Through an archival intervention that departs from the more methodical conventions, spectators must contend with sensorial and experiential ways of knowing and learning instead. The artform calls upon an engagement with the characters, in a way that feels instinctively different than if the spectators were to encounter them as statistics on the news, or in institutional archives. And even then, would the characters, who remain unidentifiable non-heroes throughout the performance, make it to the pages of History? While the question of whose stories make it to the stage is an important one too (and beyond the scope of this piece), I wonder what stories come to light when we turn to theatre, as an archive in motion. From the moment I sit on the red corduroy seat, it feels like a plunge into the void, as I accompany the characters in their state of suspension, unable to anticipate what happens to them next. What one retains from this experience is how their circumstances shape - and are shaped by - a temporality attuned to political violence and to the uncertainties that loom large because of it.

By archiving a sense of time that is not universally apprehended nor always understood, what becomes clear is the stark distance that stands between the main characters and those they encounter in exile. I feel a subtle catharsis in seeing something as real and relatable as temporal dissonances reenacted between people - especially the intricate ways that they seep into social interactions - how they contribute to social alienation and breed distance between people. This prevents the characters from building meaningful rapport or feeling understood by those around them. It’s bittersweet to witness such scenes, realizing that my strong appetite for them is partly due to how dire mainstream cultural representations tend to be when it comes to portraying people from the region.

Nonetheless, the spectator gets a sense of what it’s like to grapple with an institutionalized temporal order, whose conscripts must tacitly accept assumptions like the wellbeing of an (often European) here, versus the carnage of a horrific there, or the notion that safety is now, and violence is past. The characters remind us that there is no seamless rupture from everything that was. They challenge figments of liberal imagination like the myth of safety in ‘arrival,’ and the paradisal quality often attached to it. Administrative practices of border and immigration agencies come to mind - interviews and paperwork that refugees must go through, divulging their trauma in chronological fashion up until their arrival to ‘safety’ in Europe. The play feels like an intentional turn away from the politics of recognition and instruments of governmentality that this evidentiary form of narration is entangled with; how it is commonly used to demonstrate one’s deservingness to seek refuge in a ‘host’ society. Instead, ‘A summary of everything that was,’ offers an alternative, humanizing modality of storytelling.

‘A summary of everything that was’ traces the characters’ experience and relationship to time, through a disorienting, non-linear performance. The spectator sits close to the human mind through this mode of narration. I feel as though I’ve crawled into someone’s brain, vividly bearing witness to their interiority; their racing thoughts that scream on the inside, while the acoustics of their skin render their reflections at times mute from the outside. What does this sort of theatrical immersion invite? This psychological proximity reminds of Saidiya Hartman’s practice of critical fabulation, in that it offers a mode of close narration that challenges a common disciplinary tendency to sever the author and the personal from the process of historical writing and expression at large. In this case, the line between character and narrator is blurred. The actors embody both roles, which provides an opening ripe with possibilities for crafting intimate stories about ‘everything that was.’ As I follow their speech and movements, however, I feel too close to them, and it’s not always easy to distinguish their inner voice from what they outwardly express. Their monologues at times feel crafted in surrealist, automatist fashion -as though they are not in control over their diction.

The spectator is dizzy, or at least I am - oscillating between deep dives into what feels like the characters’ inner worlds, and instances of external release, which show up as eruptions of fragmented thoughts.

The production archives an alternative relationship to time by challenging story-telling conventions; it becomes quickly clear that it doesn’t have an expected sequence of events, the narrative arc is absent, the characters are not clearly charted, and the places from which they speak are not always obvious. How can one then trace the time of a story – an ambitious synthesis of ‘everything’ as the title suggests, in the absence of a narrative thread? The play unsettles a desire for mastery – as Julietta Singh would describe. In this case, mastery over time; the ability to organize, classify, and chart a time-line. With this common inclination for control comes a disposition towards linearity - the comforting logic used to make sense of time.

Instead, the spectator is forced into a freefall alongside the characters who are experiencing it. Here, there is no series of events that can be neatly presented to factually recount ‘a summary of everything.’ And this doesn’t seem to be the point. Through an archival intervention that departs from the more methodical conventions, spectators must contend with sensorial and experiential ways of knowing and learning instead. The artform calls upon an engagement with the characters, in a way that feels instinctively different than if the spectators were to encounter them as statistics on the news, or in institutional archives. And even then, would the characters, who remain unidentifiable non-heroes throughout the performance, make it to the pages of History? While the question of whose stories make it to the stage is an important one too (and beyond the scope of this piece), I wonder what stories come to light when we turn to theatre, as an archive in motion. From the moment I sit on the red corduroy seat, it feels like a plunge into the void, as I accompany the characters in their state of suspension, unable to anticipate what happens to them next. What one retains from this experience is how their circumstances shape - and are shaped by - a temporality attuned to political violence and to the uncertainties that loom large because of it.

By archiving a sense of time that is not universally apprehended nor always understood, what becomes clear is the stark distance that stands between the main characters and those they encounter in exile. I feel a subtle catharsis in seeing something as real and relatable as temporal dissonances reenacted between people - especially the intricate ways that they seep into social interactions - how they contribute to social alienation and breed distance between people. This prevents the characters from building meaningful rapport or feeling understood by those around them. It’s bittersweet to witness such scenes, realizing that my strong appetite for them is partly due to how dire mainstream cultural representations tend to be when it comes to portraying people from the region.

Nonetheless, the spectator gets a sense of what it’s like to grapple with an institutionalized temporal order, whose conscripts must tacitly accept assumptions like the wellbeing of an (often European) here, versus the carnage of a horrific there, or the notion that safety is now, and violence is past. The characters remind us that there is no seamless rupture from everything that was. They challenge figments of liberal imagination like the myth of safety in ‘arrival,’ and the paradisal quality often attached to it. Administrative practices of border and immigration agencies come to mind - interviews and paperwork that refugees must go through, divulging their trauma in chronological fashion up until their arrival to ‘safety’ in Europe. The play feels like an intentional turn away from the politics of recognition and instruments of governmentality that this evidentiary form of narration is entangled with; how it is commonly used to demonstrate one’s deservingness to seek refuge in a ‘host’ society. Instead, ‘A summary of everything that was,’ offers an alternative, humanizing modality of storytelling.

The Body as Archive

Abbas’ script absorbs my attention. I read it on screen while simultaneously trying to observe the characters speaking. Though, every so often, non-verbal forms of communication take center stage. Their body movements sometimes appear free-flowing and unbound by dance rules and conventions, while at other points, they take place within the contours of what seems to me like a clearer choreography. Overall, this kinetic work is a key component of the story-telling practice and forms part of a broader theatre language used to perform an archive of ‘everything that was.’ There is an enduring quality to the knowledge imparted through the characters’ physical movements. They come with a heavy affective charge that one can feel across the auditorium – one that changes the emotions of the space, reminding me of how Diana Evans once described ‘dance’ as ‘a fevered writing of oneself across the air.’

Amongst the most gripping scenes for me, is when the characters indulge in what I perceive as Berlin’s rave scene. I watch them dance amidst a nocturnal culture that provides them with a temporary release -a stage for movement, anonymity, and self-expression under enchanting strobe lights. Beneath their nightlife indulgences, however, lie struggles that cannot be neatly containable nor left at the club door. They are enmeshed within the characters’ everyday life experiences in Germany, resurfacing at different intervals -a social interaction or bad trip away from being activated. Through the characters’ movements, the play foregrounds this impossibility of detachment: the body cannot surrender to ‘the present moment’ in how it is conventionally understood. No amount of dancing or substances can sedate memories of home and war, nor the struggles of exile.

The characters chart emotions that seem difficult to express through speech alone. The notion of ‘the body as an archive’ is not just a metaphor here, but a testament to its sovereignty, in how it retains and transmits lived experience as knowledge. I think of Julietta Singh’s writings on the cumulative ways that violence leaves bodily traces -a form of haunting that comes to light under certain conditions. Though deeply intimate and seemingly individual in scope, the characters’ movements become a soundboard through which broader reflections on structural violence can take place.

Abbas’ script absorbs my attention. I read it on screen while simultaneously trying to observe the characters speaking. Though, every so often, non-verbal forms of communication take center stage. Their body movements sometimes appear free-flowing and unbound by dance rules and conventions, while at other points, they take place within the contours of what seems to me like a clearer choreography. Overall, this kinetic work is a key component of the story-telling practice and forms part of a broader theatre language used to perform an archive of ‘everything that was.’ There is an enduring quality to the knowledge imparted through the characters’ physical movements. They come with a heavy affective charge that one can feel across the auditorium – one that changes the emotions of the space, reminding me of how Diana Evans once described ‘dance’ as ‘a fevered writing of oneself across the air.’

Amongst the most gripping scenes for me, is when the characters indulge in what I perceive as Berlin’s rave scene. I watch them dance amidst a nocturnal culture that provides them with a temporary release -a stage for movement, anonymity, and self-expression under enchanting strobe lights. Beneath their nightlife indulgences, however, lie struggles that cannot be neatly containable nor left at the club door. They are enmeshed within the characters’ everyday life experiences in Germany, resurfacing at different intervals -a social interaction or bad trip away from being activated. Through the characters’ movements, the play foregrounds this impossibility of detachment: the body cannot surrender to ‘the present moment’ in how it is conventionally understood. No amount of dancing or substances can sedate memories of home and war, nor the struggles of exile.

The characters chart emotions that seem difficult to express through speech alone. The notion of ‘the body as an archive’ is not just a metaphor here, but a testament to its sovereignty, in how it retains and transmits lived experience as knowledge. I think of Julietta Singh’s writings on the cumulative ways that violence leaves bodily traces -a form of haunting that comes to light under certain conditions. Though deeply intimate and seemingly individual in scope, the characters’ movements become a soundboard through which broader reflections on structural violence can take place.

How does the collective body heal?

We accompany the characters on (what feels to me like internal) monologues in Arabic, through which their inner worlds unfurl, journeying through a spiral of emotions and reflections on war and exile. These scenes are unnerving. They provide public access to thoughts that are not often heard by refugees and exiles in the German public eye. As the characters’ streams of consciousness absorb the viewer, they are suddenly interrupted by prosaic encounters with ‘the outside’ world -interactions that are oftentimes coated with a level of superficiality; when a (presumably German) stranger at the club, or an officer, abruptly interject – as if waking one up from a dream - to make small talk, interrogate them, or simply ask: Are you alright?

Such ‘wake-up’ calls bring me back to the constrictive temporal logic that does not account for the many who are disproportionately grappling with the ongoing effects of protracted war and displacement. It speaks to the bodily violence of needing to ‘move on’ from ‘the past’ in pseudo-progressivist fashion, while a pungent scent of strife, bloodshed, and injustice still lingers in the air.

We accompany the characters on (what feels to me like internal) monologues in Arabic, through which their inner worlds unfurl, journeying through a spiral of emotions and reflections on war and exile. These scenes are unnerving. They provide public access to thoughts that are not often heard by refugees and exiles in the German public eye. As the characters’ streams of consciousness absorb the viewer, they are suddenly interrupted by prosaic encounters with ‘the outside’ world -interactions that are oftentimes coated with a level of superficiality; when a (presumably German) stranger at the club, or an officer, abruptly interject – as if waking one up from a dream - to make small talk, interrogate them, or simply ask: Are you alright?

Such ‘wake-up’ calls bring me back to the constrictive temporal logic that does not account for the many who are disproportionately grappling with the ongoing effects of protracted war and displacement. It speaks to the bodily violence of needing to ‘move on’ from ‘the past’ in pseudo-progressivist fashion, while a pungent scent of strife, bloodshed, and injustice still lingers in the air.

Move on, move on, move on.

Artist Hayv Kahraman (whose exhibit Gut Feelings explored the effects of trauma on the body) has spoken of how her work is shaped by this deep attunement to the body’s capacity to store, as well as by a sensitivity to our current moment, in which extractive demands for refugee trauma ‘contribute to an economy of pain where suffering becomes the currency.’ Abbas’ play intervenes within this political climate that is saturated with romanticized depictions of refugee victimhood and suffering, while refusing to capitalize on its currency. Though the play at times reveals distressing states of being, its register is contemplative; it does not elicit a voyeuristic nor pitiful gaze.

‘A summary of everything that was’

In the last scene of the play, we are confronted with immersive, background footage of decimated Syrian cities. As we visually glide through the ruinscape at an accelerating pace, the characters stand in close embrace, facing the audience. They look into the distance, as though searching into the abyss and asking themselves: what lies on the horizon, beyond the rubble? What are we heading towards? What future awaits?

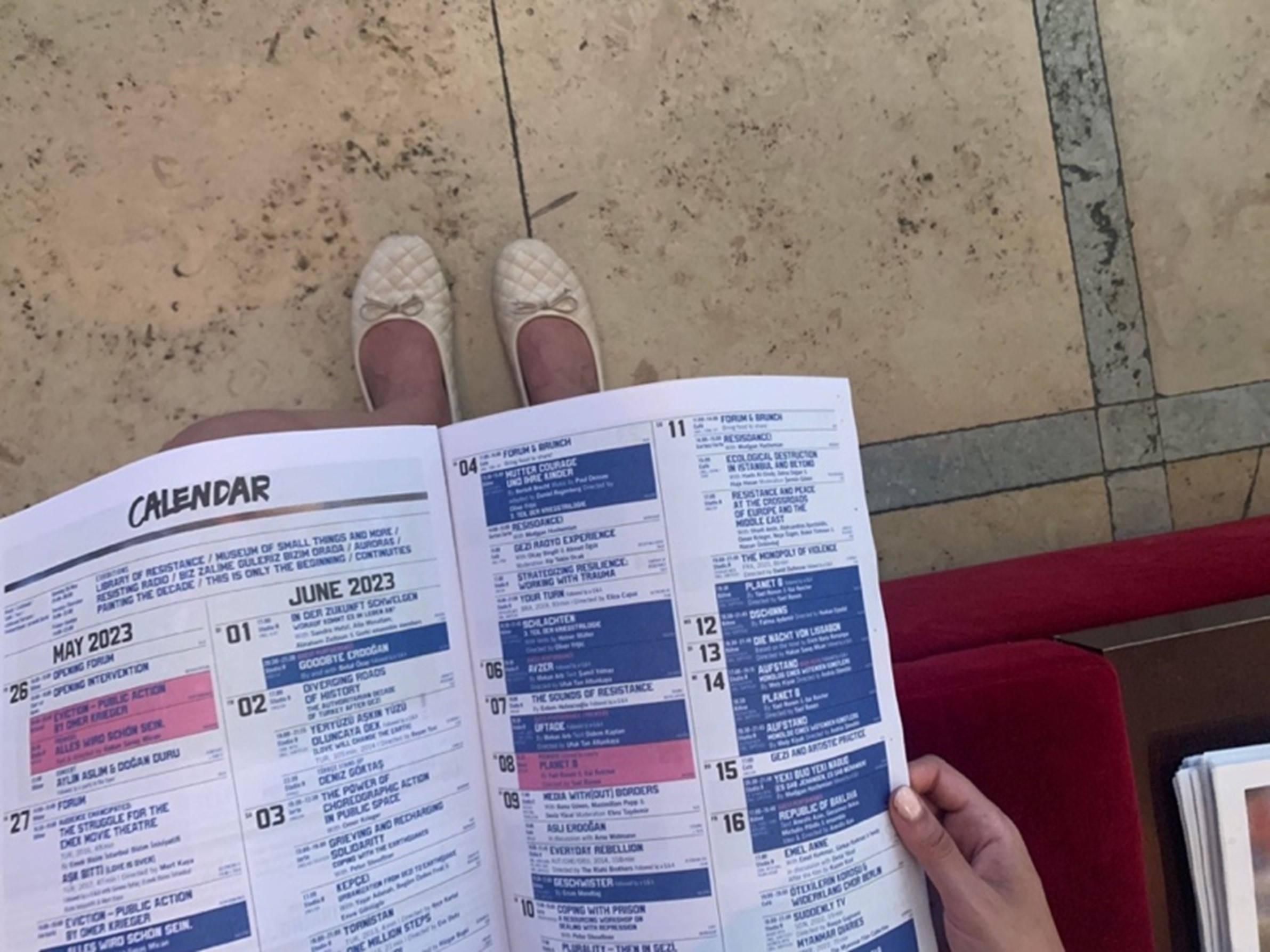

Alongside institutional archives, often revered as time capsules brimming with bygone treasures (waiting to be studied by those with permission to write History), 'A summary of everything that was’ lends itself to a more expansive archival practice and intervention – one that encourages us to venture beyond methodically organized texts, to contemplate the value of socially engaged art in exploring the post-Arab Spring moment in its multi-dimensionality. At times when regressive regimes across the region are increasingly encroached on public life and space, one can situate the play within a broader cultural landscape in exile that continues to grapple with recent pasts, still tender in their wounds, with no political horizon yet in sight. Artistic interventions of this sort confront the ‘void’ as a matter of political concern, speaking to a state of collective suspension – not necessarily in a romantic nor fetishistic manner, but in a way that largely marks our historical juncture. ‘A summary of everything that was’ intervenes in this vein, archiving embodied experiences that seldom make it to the pages of History. It captures how the characters experience social landscapes in flux – ones that nonetheless remain consistent in their worsening material conditions and hostile environments. The play digs into the poetics of this space-time that is often hidden from public view. It does so by exploring how an experience of time functions when the banalities of everyday life sit alongside monstrous violence. A conversation unfolds between the characters and the audience in the process – one that looks at the afflictions that bind us, imploring us to confront them, even when the dust has not yet settled.

A special thank you to Dr Anne-Marie McManus, Clara Cirdan, Babette May, and Sania Khan for the feedback and generative conversations that helped shape some ideas developed in this piece.

Artist Hayv Kahraman (whose exhibit Gut Feelings explored the effects of trauma on the body) has spoken of how her work is shaped by this deep attunement to the body’s capacity to store, as well as by a sensitivity to our current moment, in which extractive demands for refugee trauma ‘contribute to an economy of pain where suffering becomes the currency.’ Abbas’ play intervenes within this political climate that is saturated with romanticized depictions of refugee victimhood and suffering, while refusing to capitalize on its currency. Though the play at times reveals distressing states of being, its register is contemplative; it does not elicit a voyeuristic nor pitiful gaze.

‘A summary of everything that was’

In the last scene of the play, we are confronted with immersive, background footage of decimated Syrian cities. As we visually glide through the ruinscape at an accelerating pace, the characters stand in close embrace, facing the audience. They look into the distance, as though searching into the abyss and asking themselves: what lies on the horizon, beyond the rubble? What are we heading towards? What future awaits?

Alongside institutional archives, often revered as time capsules brimming with bygone treasures (waiting to be studied by those with permission to write History), 'A summary of everything that was’ lends itself to a more expansive archival practice and intervention – one that encourages us to venture beyond methodically organized texts, to contemplate the value of socially engaged art in exploring the post-Arab Spring moment in its multi-dimensionality. At times when regressive regimes across the region are increasingly encroached on public life and space, one can situate the play within a broader cultural landscape in exile that continues to grapple with recent pasts, still tender in their wounds, with no political horizon yet in sight. Artistic interventions of this sort confront the ‘void’ as a matter of political concern, speaking to a state of collective suspension – not necessarily in a romantic nor fetishistic manner, but in a way that largely marks our historical juncture. ‘A summary of everything that was’ intervenes in this vein, archiving embodied experiences that seldom make it to the pages of History. It captures how the characters experience social landscapes in flux – ones that nonetheless remain consistent in their worsening material conditions and hostile environments. The play digs into the poetics of this space-time that is often hidden from public view. It does so by exploring how an experience of time functions when the banalities of everyday life sit alongside monstrous violence. A conversation unfolds between the characters and the audience in the process – one that looks at the afflictions that bind us, imploring us to confront them, even when the dust has not yet settled.

A special thank you to Dr Anne-Marie McManus, Clara Cirdan, Babette May, and Sania Khan for the feedback and generative conversations that helped shape some ideas developed in this piece.

Yasmine Kherfi is a London-based writer, editor, and researcher. She is currently a PhD candidate in Sociology at the London School of Economics, where her project explores entanglements between revolution, collective memory and cultural production in the aftermath of the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings. Prior to her PhD, Yasmine administered research projects as part of the LSE Middle East Centre’s collaboration programme with Arab universities. She holds a master’s from the Bartlett Development Planning Unit at University College London, and a BA in Middle East studies and political science from the University of Toronto. With experience working in the cultural sector, Yasmine occasionally curates events centering on solidarity and regional struggles.