Mohanad Yaqoubi

The Tokyo Reels

~

Prologue

After a screening of the film “Off Frame Aka

Revolution Until Victory, 2016” at image Forum cinema in Shibuya,

Tokyo, a member of the audience approached us with a piece of paper. She asked

to meet before we leave Japan. The paper contained a sort of a list, mainly in

Japanese mixed with some English, and after a quick translation we realized it

was a list of films about the Palestinian struggle.

A year after this encounter, the guardians of the collection took us to a place in the outskirts of Tokyo, a small room in a traditional Japanese house. It turned out to be a home to an archive: film reels, U-matic, photographs, books, posters, documents, among other things, kept there for over three decades. The collection covers the 1970s and ‘80s Japanese solidarity activism with the Palestinian cause.

The collection is safeguarded by people who were active in that scene, Mineo Mitsui and Aoe Tanami, and they kindly granted us access to the 16 mm film reels, which we picked up and transported to the Film lab of KASK, School of the Arts, Gent.

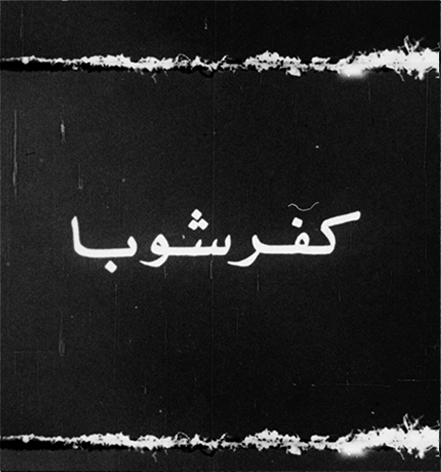

The Collection contains 20 film reels, all 16 mm format, all Positive prints. Very little information can be extracted from the packaging, yet there are several fascinating iconographies that can be noticed on the reels tin covers, logos on the casing, addresses, contact numbers, the wrapping materials; the amount of work put in each reel to reach the distribution can be traced.

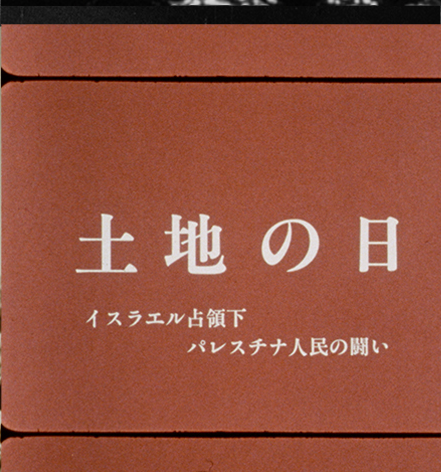

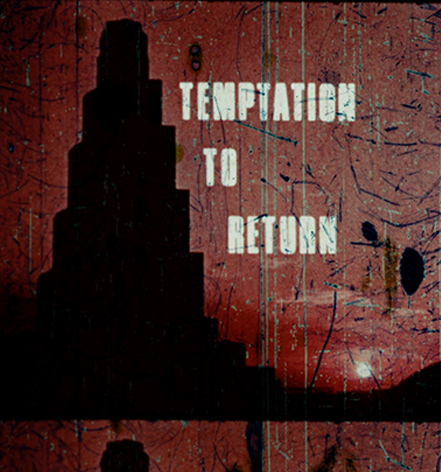

Although the list we got with the collection had some crucial information about the distribution, it was still hard to form an idea of what we were dealing with. We realized that many film titles were translated to English from the Japanese title that had been given when the films were adapted to Japanese audience. And since we didn’t know what was in the collection, we gradually started to refer to it as “The Tokyo Reels”.

The first mission was to study the inventory we got from the guardians of the collection, to edit the inventory in a formal and coherent way, to update the original inventory, to add the comparative reflection, and to add all necessary information related to the production of these films.

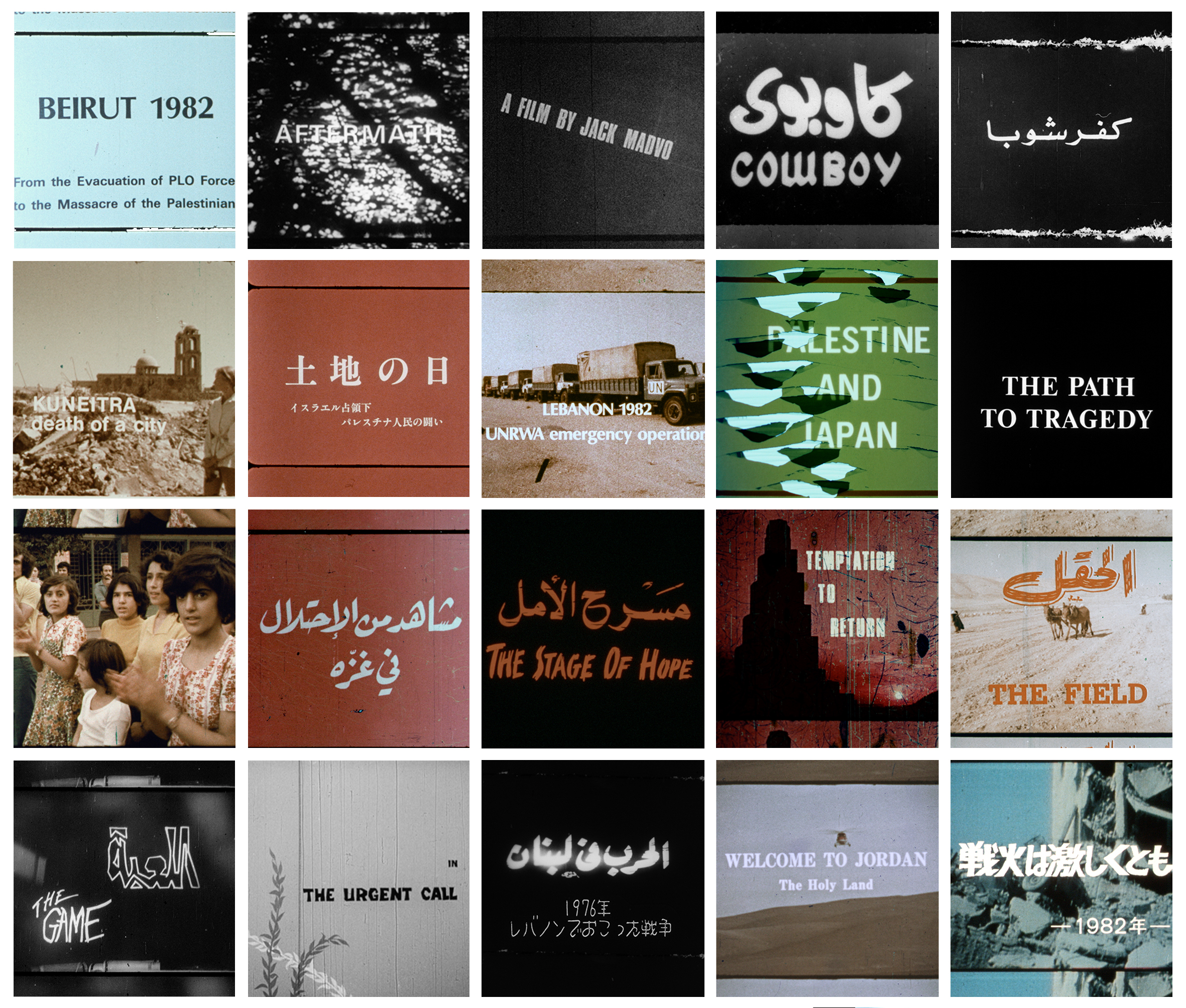

Following a quick scan, the uniqueness of the collection became obvious. The twenty film reels, packaged in canisters and boxes labeled and marked with film titles, dates, and some production and distribution details, present a collection of films rendering a history of political mobilisation and solidarity with Palestine specific to Japan at the time.

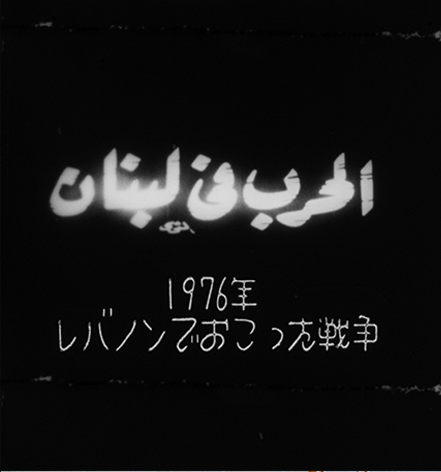

The films were made by Palestinian, Arab, Japanese and international filmmakers and journalists, and were commissioned by various political bodies, TV stations, and humanitarian organizations. They contain different modes of adaptation, translation, dubbing, re-editing from the orginal version of the films, that included adding photographs with captions and interviews to contextualise the films about the struggle to Japanese audience.

A year after this encounter, the guardians of the collection took us to a place in the outskirts of Tokyo, a small room in a traditional Japanese house. It turned out to be a home to an archive: film reels, U-matic, photographs, books, posters, documents, among other things, kept there for over three decades. The collection covers the 1970s and ‘80s Japanese solidarity activism with the Palestinian cause.

The collection is safeguarded by people who were active in that scene, Mineo Mitsui and Aoe Tanami, and they kindly granted us access to the 16 mm film reels, which we picked up and transported to the Film lab of KASK, School of the Arts, Gent.

The Collection contains 20 film reels, all 16 mm format, all Positive prints. Very little information can be extracted from the packaging, yet there are several fascinating iconographies that can be noticed on the reels tin covers, logos on the casing, addresses, contact numbers, the wrapping materials; the amount of work put in each reel to reach the distribution can be traced.

Although the list we got with the collection had some crucial information about the distribution, it was still hard to form an idea of what we were dealing with. We realized that many film titles were translated to English from the Japanese title that had been given when the films were adapted to Japanese audience. And since we didn’t know what was in the collection, we gradually started to refer to it as “The Tokyo Reels”.

The first mission was to study the inventory we got from the guardians of the collection, to edit the inventory in a formal and coherent way, to update the original inventory, to add the comparative reflection, and to add all necessary information related to the production of these films.

Following a quick scan, the uniqueness of the collection became obvious. The twenty film reels, packaged in canisters and boxes labeled and marked with film titles, dates, and some production and distribution details, present a collection of films rendering a history of political mobilisation and solidarity with Palestine specific to Japan at the time.

The films were made by Palestinian, Arab, Japanese and international filmmakers and journalists, and were commissioned by various political bodies, TV stations, and humanitarian organizations. They contain different modes of adaptation, translation, dubbing, re-editing from the orginal version of the films, that included adding photographs with captions and interviews to contextualise the films about the struggle to Japanese audience.

Questions

Once the collection arrived at the lab at KASK in Gent for investigation, many questions have already been formulated. Some were technical, some cinematic, others were political. It was like starting from a blank page, to start writing a new account about this history. There weren’t many texts to read about the Japanese solidarity movement with the Palestinian struggle, at least not in English and Arabic, so we tried to formulate some questions; not to seek answers, but rather as much as guiding lines to lead our thinking and give inspiration.

- Can we read the politics of a solidarity by looking at a collection of films? Can we write a history of

solidarity only by watching films?

-

What can the information in the reels tell us about the origin of the collection? And who are the people behind it?

-

Who

was behind the circulation? And what were the audience

reactions?

-

What

does it mean to screen these films today? And what

does it mean to screen

the films together, as a collection?

-

How do we position

transnational film collections in the age of identity politics?

raising questions such as is it a Palestinian collection? a Japanese? and what does it mean to represent a struggle

of another people, cinematically and politically.

The origin of the collection

It is hard to pinpoint the exact history and origin of the collection, mainly because several people who were part of or related to the PLO office in Tokyo have passed away, but also because the Palestinian question is still an ongoing struggle, there is a need to be cautious about exposing a network of solidarity that is still partly in action. It’s important to keep in mind that this is not an institutional archive, and in some way, it resists the status of being official or final, as this would indicate the end of the struggle through the very act of archiving it.

From this perspective, Subversive Film approach the question of origins by adopting two methods. The first is by interviewing the guardians of the collection, who gave an account of how this collection came into their care. The second method is through connecting the dots emerging from the films themselves—analysing the credits, captions, information that appears on the film strips and the canisters in which the reels are kept—all while keeping in mind the parallel political event that might or would affect the selection of the film, for example, the Sabra and Shatila massacre, where we noticed several titles related to this event, or the consequences of the June 1973 war, that disturbed the energy supply chain around the world including Japan and rose attention to the Palestinian struggle.

[1] for the

wider perspective, read “The Red Years: Theory,

Politics, and Aesthetics in the Japanese ’68”, Edited by Gavin Walker, Verso

Books, 2020

This allowed us

to build a narrative around the origin of the collection, that is “non-fictional”,

or to be more precise, a speculative, imagined narrative, yet rooted in

historical reality, with an anti-imperialist perspective, which was beside the

transnational solidarity politics, the dominant ideological framework for the

new Japanese left movement[1].

[2] An Excerpt from

Minoe Mitsui interview with Subversive Film, Kassel 2022

During an

interview with Mineo Mitsue, one of the collection caretakers, he said that they

were not the ones who collected all the films, but his words gave us sense of

its origin: “When they closed the office, one of the Japanese staff who was

working at the PLO office then called me and asked for some favours. He was asking

where to send some papers, and which storage they should go to. But for the

films and videos, he decided to leave them with me. It was quite a lot of

things to store just by myself. In the beginning, I didn’t know what to do with

them. First, I approached the Christian United Church of Japan, and asked if

they could spare storage for them. After that I also approached a professor of

Arabic at the Foreign Language University in Japan, but that was also declined.

So, at the end, through the introduction of that professor, I met Tanami San,

she was a student by then, and she agreed to keep the collection.”[2]

Reflections

on Digitization

The first step was to dive into the collection, to forensically document the process of investigation and to upgrade and complete the inventory. This required photographing all the details on the reels cannisters, creating folders for every reel, collecting relevant information, and translating them. the next step was to dive into the materiality of the film reels, beside analyzing the content, the reels needed preparation before digitization. It was necessary to know what type of each film material and its condition, check the acidity levels and the conditions of each reel, and then clean them.

The initial report made us realise that all the reels are in a positive format, which is the screening format of the 16mm. All the films were with optical sound, except one, which had a magnetic audio strip on the film. Most of them were in good condition, an indication that they hadn’t been screened many times. There were some reels infected with the vinegar syndrome, which were important to spot and separate from the rest of the collection. One reel, which is titled “Palestine to Japan”, was damaged and needed special treatment to digitize. We managed this but with a lot of scratches and deformed frames, though the soundtrack of the film was fine.

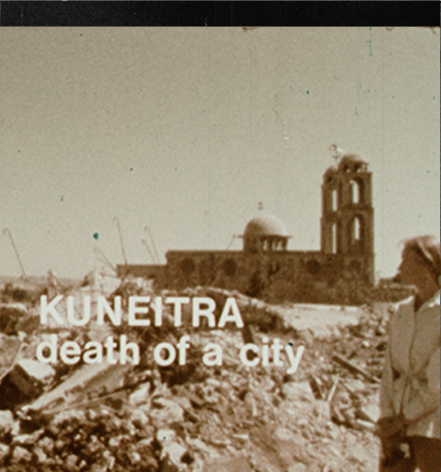

Following this analysis, the reels were pulled to the scanner by adding a lead film tape to ensure that all film frames are captured. For each film, the title, the director, and all other crew credits were transcribed, and slowly the map of the collection started to be clearer. It contained films produced between 1964 and 1982, and most of them are about the Palestinian question and struggle. There are some films that addressed other topics, mainly revolving around the question of modernity in the Arab world.

Digitizing the collection was also a form of study through which we learned about the independent Japanese political film screening practices, from the labels left on the reels’ canisters, to the handwritten notes on the cullieds themselves, to the programing notes left sticking on the bottom of the cannisters. One reel was wrapped in a newspaper dated from September 1982, and another reel had two films attached together. Some films had information of production houses in Japan.

This form of restoration enabled thorough access to each film individually, and to the collection as a whole, by watching the films together, with the ability to stop, rewind, compare with other films in the collection, studying the voice over, or a recurring credit, building a pattern that indicates a history that can be read through its traces. When all these details, symbols, images, texts were combined in one folder, patterns started to emerge, making it clear how these films came to Japan, and how they overlapped with a historical and geopolitical map; categorization became more possible.

Speculation as history

Some of the films were quite well known in the milieu of research on Palestine and cinema, but most of them were rare titles, and films that have not been screened widely. Some were copies of films that were considered lost, or with no access to a good 16mm copy. After scanning all the films, it was interesting to notice that the common pattern between all of them is the absence of films made under and with more radical leftist politics.

This absence can be read as indicative of the political orientation of the solidarity scene with Palestine that gathered and safeguarded this collection, made up of a segment of the Japanese left that denounced violence and armed struggle as a method of social change. This segment contrasts with the Red Japanese army (and other Japanese factions from the New Japanese Left), who were also associated with the Palestinian struggle at some point, and who trained in PLO military factions’ camps, running stunning hijacking operations against the Israeli State.

It was the Lod Airport operation in May 1972, where 26 people were killed after members of the Japanese Red Army (JRA) where trapped and forced to open fire in the middle of the airport. This specific event led to a massive crack down by the Japanese security forces on members of many left movements back in Japan, arresting members of the Japanese United Army, and keeping an eye on any political event, especially ones related to solidarity with Palestine.

[3] Except from

a letter by Prof. Aoe Tanami send to Subversive Film in the summer of 2022.

The aggressive approach that was adopted by the

Japanese authorities can be seen in the case of Dr. Takako Nobuhara, a Japanese

doctor who volunteered at Palestinian clinics in Beirut during the Israeli

invasion in 1982. Her passport was burned after her apartment was destroyed

following an Israeli air raid on the city. Later, she was denied the right to a

new passport by the Japanese authorities and was stranded in Lebanon for more than

10 years. Her case mobilized several activists back home in Japan including Professor

Aoe Tanami, one of the collection’s guardians. She mentions in her letter to

Subversive Film that “Solidarity Movement had nothing to do with the JRA, nor

was it ideologically influenced by the JRA. If I were to look for

"influence," I would say that I met several people who were involved

in activities to support a female doctor who was denied reissue of her passport

by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs because of her suspected ties to

the JRA.”[3]

Such a political climate obviously reflects on the selection of the films in the collection, keeping the content of the films focused on the educational, informative, and humanitarian level throughout the collection, with no connection to the JRA and its rhetoric, and with no controversial and militant messaging that might attract the attention of the Japanese security forces.

The fact that the collection has flourished within the PLO office in Tokyo also meant that the Palestinian films in the collection were produced mainly by its filmic departments, such as the Palestinian Cinema Institute, the Cultural Art Section of the Unified Media, and Al-Sakhra Studios. Other films were produced by state run film institutes in countries such as Iraq, Syria Jordan and Kuwait, and one can speculate that they came into the collection from the diplomatic missions surrounding the PLO in Tokyo. The rest were mainly Japanese productions on the Palestinian question.

While we are still researching and speculating on the meaning of creating an archive of a transnational solidarity movement, all the films where transcribed and translated into three languages, Arabic, Japanese and English. New synopses were written for each film, credits and still images from the films were compiled in a publication that is available in pdf form on the website www.tokyoreels.com, hoping that it will expand our understanding of what it mean to archive a revolution.

Such a political climate obviously reflects on the selection of the films in the collection, keeping the content of the films focused on the educational, informative, and humanitarian level throughout the collection, with no connection to the JRA and its rhetoric, and with no controversial and militant messaging that might attract the attention of the Japanese security forces.

The fact that the collection has flourished within the PLO office in Tokyo also meant that the Palestinian films in the collection were produced mainly by its filmic departments, such as the Palestinian Cinema Institute, the Cultural Art Section of the Unified Media, and Al-Sakhra Studios. Other films were produced by state run film institutes in countries such as Iraq, Syria Jordan and Kuwait, and one can speculate that they came into the collection from the diplomatic missions surrounding the PLO in Tokyo. The rest were mainly Japanese productions on the Palestinian question.

While we are still researching and speculating on the meaning of creating an archive of a transnational solidarity movement, all the films where transcribed and translated into three languages, Arabic, Japanese and English. New synopses were written for each film, credits and still images from the films were compiled in a publication that is available in pdf form on the website www.tokyoreels.com, hoping that it will expand our understanding of what it mean to archive a revolution.

Mohanad Yaqubi is a filmmaker, producer, and one of the founders of the Ramallah-based production outfits, Idioms Film. He also teaches Film Studies at the International Art Academy in Palestine. Yaqubi is also one of the founders of the research and curatorial collective Subversive Films, that focuses on militant film practices. Yaqubi’s filmography as a producer includes the documentary feature Infiltrators (directed by Khaled Jarrar, 2013), the narrative short Pink Bullet (directed by Ramzi Hazboun), and as co-producer the narrative feature Habibi (directed by Susan Youssef, 2010) and the short narrative Though I Know the River is Dry (directed by Omar R. Hamilton, 2012). In 2013, Yaqubi initiated and produced Suspended Time, an anthology that reflected on 20 years after the signing of the Oslo Peace Accords, that included nine filmmakers. His latest film No Exit, (written with Omar Kheiry), premiered at the Dubai International Film Festival in 2015. He feature film Off Frame AKA Revolution Until Victory is making its world premiere at TIFF.

サブバーシブ・フィルム(反体制映画)とは、パレスチナとその地域に関する歴史的作品に新しい光を投げかけると共に、映画保存への支援を呼びかけ、アーカイブの手法を調査することを目的とした、映画研究・制作コレクティブである。サブバーシブ・フィルムの長期かつ進行中のプロジェクトは、映画と歴史が交わる領域を探求している。その活動には、今まで見過ごされてきた映画のデジタル版復刻、貴重な映画の上映イベントのキュレーション、再発見された映画の字幕制作、出版物の制作、その他の介入方法の考案などが含まれる。2011年に結成されたサブバーシブ・フィルムは、ラマッラーとその他の地域を拠点として活動している。

Subversive Film is a cinema research and production collective that aims to cast new light on historic works related to Palestine and the surrounding region, to engender support for film preservation and to investigate archival practices. Their long-term and ongoing projects explore this cine-historic field including digitally reissuing previously overlooked films, curating rare film screening cycles, subtitling rediscovered films, producing publications, and devising other forms of interventions. Formed in 2011, Subversive Film is based between Ramallah and Brussels.

(تحريض للأفلام) مجموعة بحث وإنتاج سينمائي تهدف إلى تسليط الضوء على أعمالٍ تاريخية مُتعلقة بفلسطين والمنطقة، بهدف توليد مصادر دعم للحفاظ على الأفلام والتحقيق في الممارسات الأرشيفيّة. تستكشف مشاريع المجموعة الحاليّة وطويلة المدى هذا الحقل السينمائي-التاريخي، بما يتضمن إعادة إصدار نسخ رقميّة من أفلام خرجت من دائرة التوزيع، وتنظيم دورات عرض للأفلام النادرة، وترجمة الأفلام المُعاد اكتشافها، وإصدار المنشورات، وابتكار أشكال أخرى من التدخلات. تأسست (تحريض للأفلام) عام ٢٠١١، ومقرها رام الله وأمكنة أخرى.