Sandra Rodríguez Castañeda

To raise one’s head high:

Living archives and subaltern bureaucracies of the Rondas Campesinas from Chota, Peru

“While it is true that more than 450 years ago the Spanish invaders murdered the last of our Incas, Atahualpa, in this heroic land of Cajamarca, today, in this same land, the rebellious spirit of the Inca Empire rises up and, like a telluric force, is embodied in you, brothers and sisters of the Ronda, so that you may continue to build a society of peace and justice, which is the desire of more than 18 million brothers and sisters who demand justice with the same cry as the great Tupac Amaru and the heroine Micaela Bastidas.”

Handwritten public statement by a rondero from Bambamarca inviting the attendees of the First Regional Congress to a different event, 1985.

It was December of 1976 when peasants in a small and dispersed rural settlement in Chota, a province of Cajamarca in the northern Peruvian Andes, organized the first iteration of what came to be known as the rondas campesinas. Initially, the rondas emerged as village-level vigilante committees responding to rising insecurity in rural areas, amid deep mistrust toward police and judicial authorities that, in their perception, catered primarily to the interests of the urban elites. Their main goal was pragmatic and immediate: to put an end to robbery –especially cattle rustling– through nightly patrols of their village territories. As these early committees quickly demonstrated their effectiveness, the model spread rapidly across neighbouring provinces in Cajamarca and Piura.

But what began as a localized response to insecurity soon expanded into a broader project of conflict resolution and moral regulation. This expansion was not a purely endogenous initiative. Daniel Idrogo, a young militant of the socialist party Patria Roja, who had supported the formation of rondas from the outset, proposed the incorporation of popular justice as a means of radicalizing the rondas, drawing inspiration from Maoist experiments with people’s justice during the Long March. This proposal introduced a transnational political imaginary –one that linked peasant self-organisation in the Peruvian highlands to a wider repertoire of revolutionary practices circulating across the tricontinental world. Unlike the Shining Path –a party whose Maoist genealogy has been extensively documented– the rondas have rarely been analysed through the lens of transnational political circulation. As Orin (Starn, 1999, p. 113) has noted, the emergence of ronda justice can be read as a transnational tale, injected by a “dream of revolution that arrived to Peru by way of Patria Roja, China, and Europe”, and shaped by processes of transculturation rather than ideological transfer.

While the rondas moved beyond their initial role as “cowwatchers” –and in doing so faced strong opposition from state authorities– they never became the vehicle of peasant revolution envisioned by Idrogo and Patria Roja. Instead, they devised a distinctive system of justice that selectively mimicked state institutions. Police and court practices were observed, adapted, and reworked into a system of everyday governance: nightly patrols, the holding of assemblies to resolve local conflicts, and the mundane tasks of taking minutes, collecting signatures, affixing seals, and producing documentary records. Written records and archival practices indeed became central technologies of administrative formality through which authority was enacted and stabilised. It is through these ordinary practices that the rondas consolidated authority, forged a new political subjectivity –the rondero– and articulated not the defence of an ancestral indigenous entelechy but the shaping of new forms of highland collectivity with the capacity to confront the state beyond the local scale. Today, a committee of this organization can be found in almost every peasant community of the Peruvian Andes,1 and the rondas can be regarded as one of the significant Latin American peasant movements of the twentieth century (Starn 1999).

1.

According to data from 2003, it is estimated that there were between 200,000 and 250,000 patrol members, grouped into some 8,000 patrol committees in 12 regions (Laos et al., 2003).

Read through their archival traces, the rondas invite a rethinking of the tricontinental not as a unified revolutionary horizon, but as a dispersed and uneven field of political experimentation. The rondas campesinas’ archive demonstrates how internationalist ideals of solidarity, justice and revolution, circulating through intercontinental networks, were engaged, translated and made durable locally not through insurrection, but through routinized forms of peasant authority, everyday practices of governance, and the construction of a subaltern bureaucratic apparatus grounded in documentation.

**

The rondas campesinas enchantment for documents and preoccupation with record keeping is replicated across their village-level committees. Contrary to the common assumption that subaltern groups do not produce written records given their poor access to education and lettered culture, the rondas not only generate documents extensively but also invest them with political and symbolic significance. Written records are not ancillary to their organisation; they are central to how legitimacy, continuity, and authority are enacted.

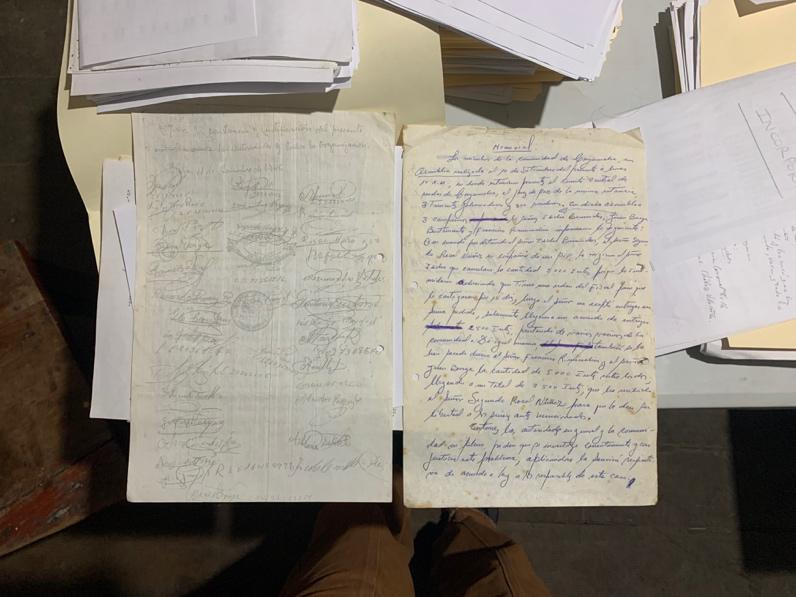

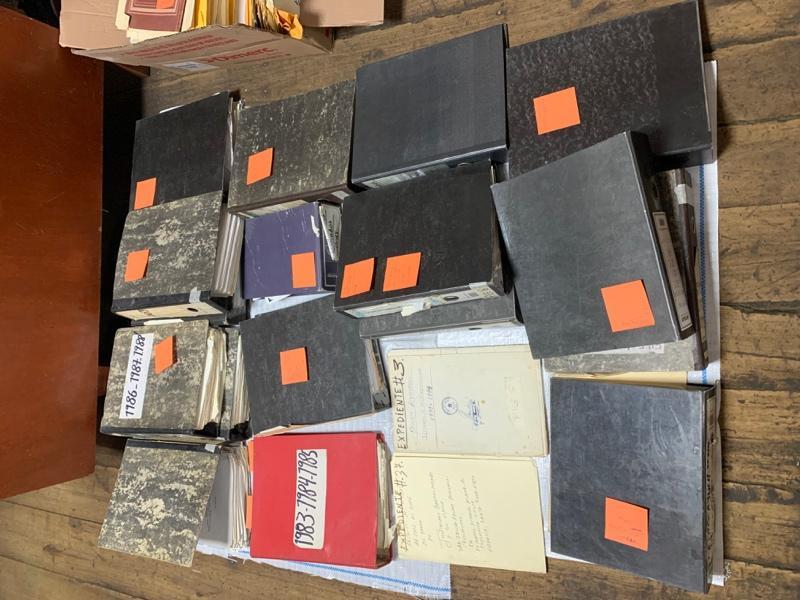

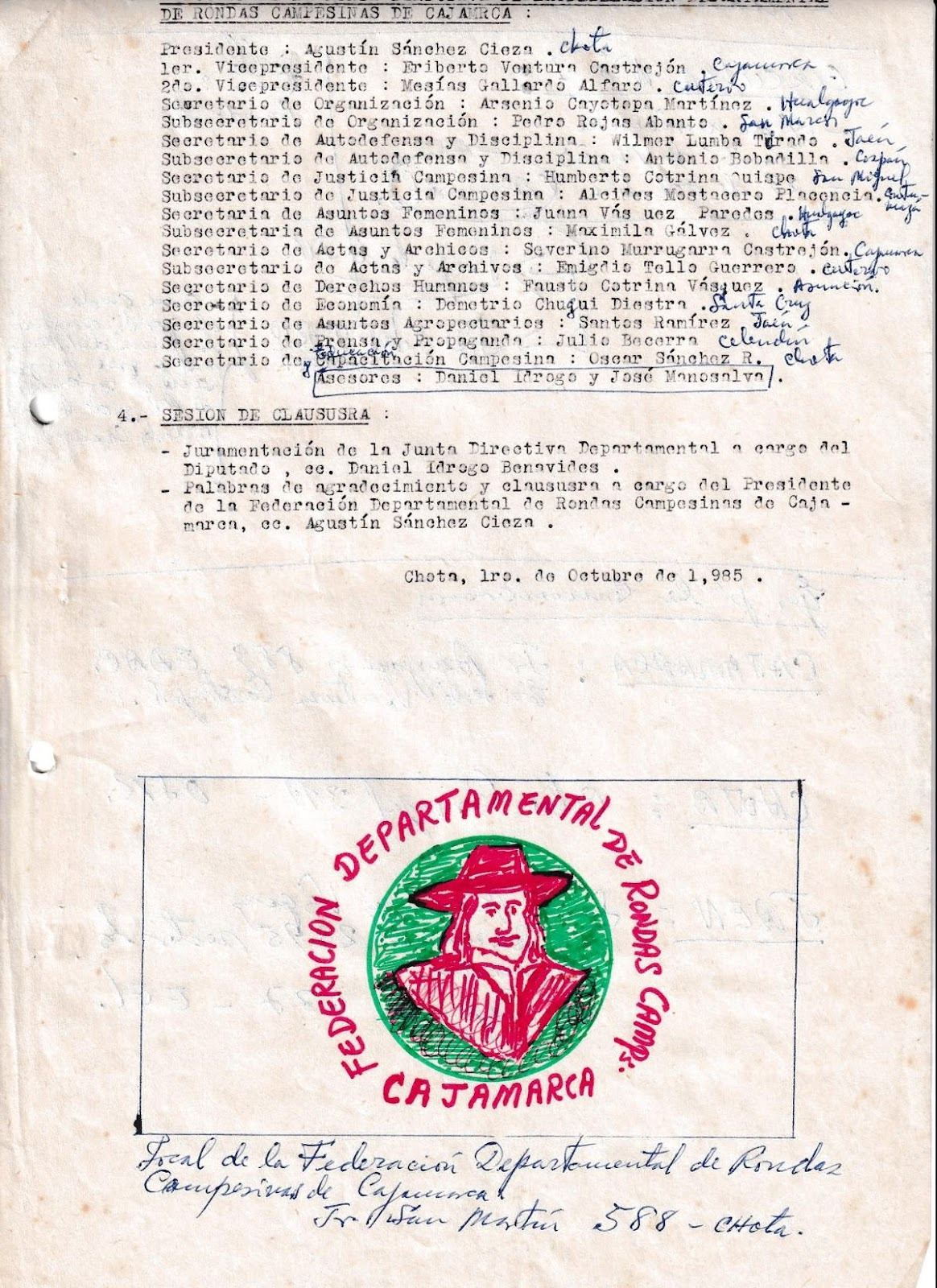

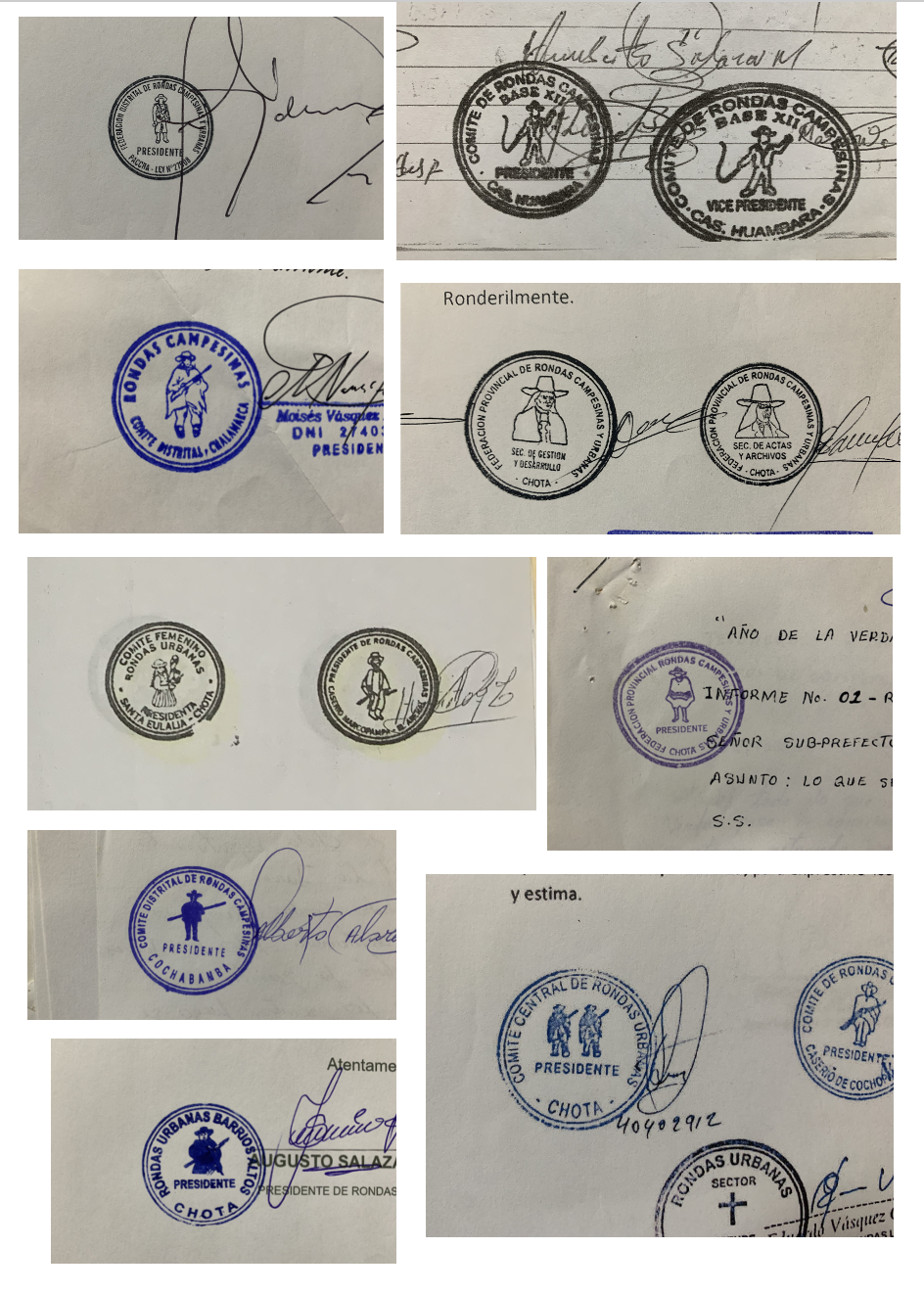

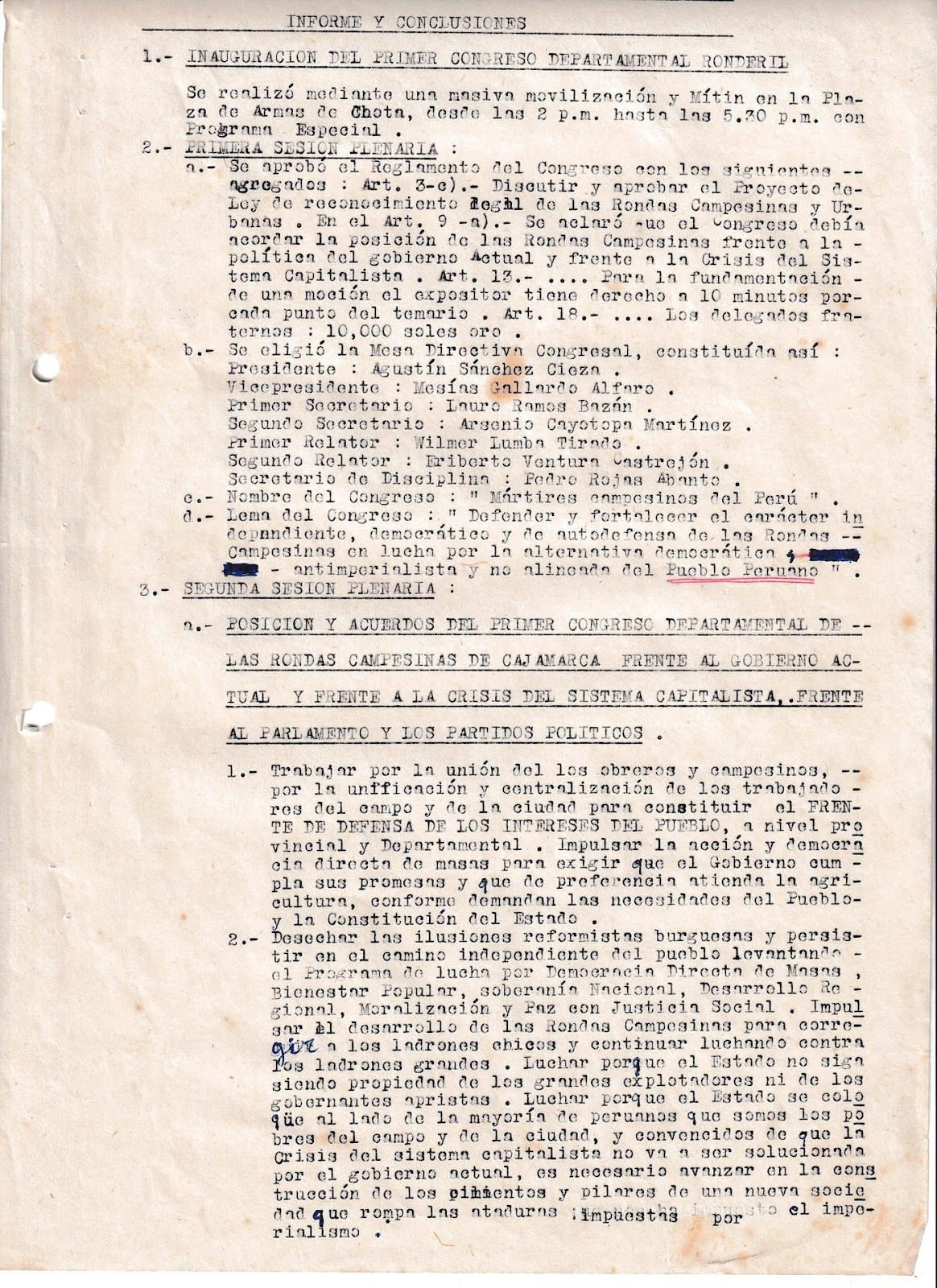

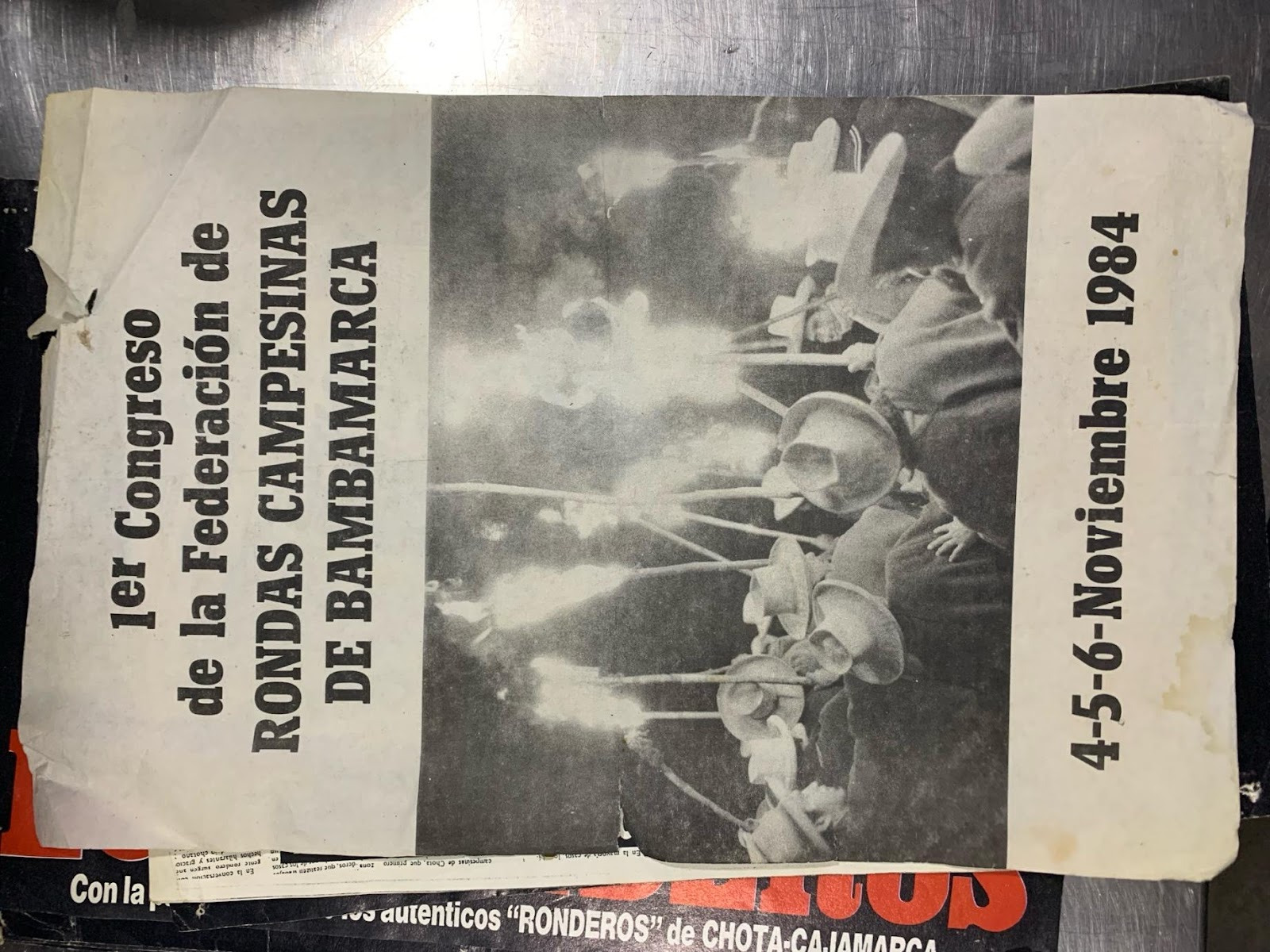

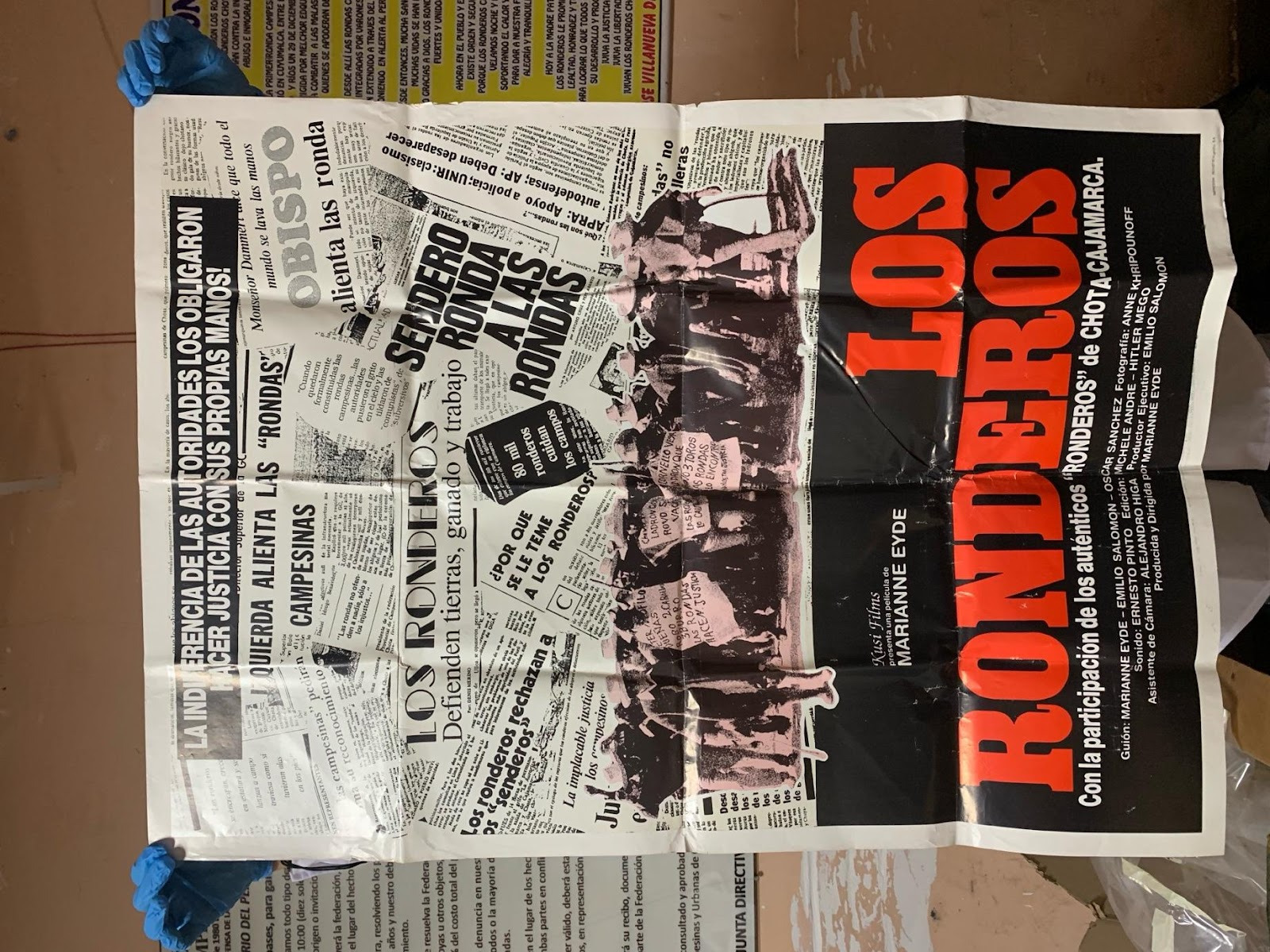

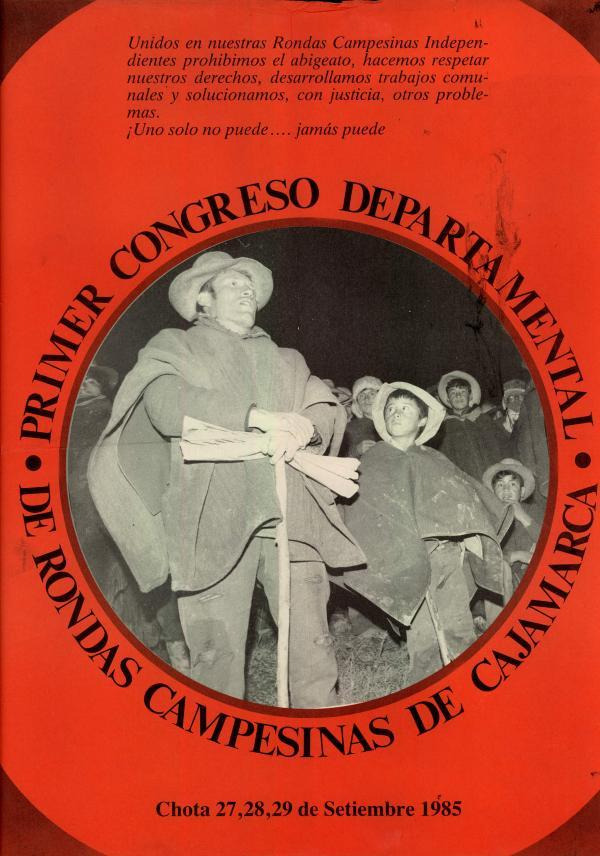

This investment in documentation becomes particularly visible in the “living archive” safeguarded by the Federación Provincial de Rondas Campesinas de Chota, which traces the organisation’s history since its emergence in the late 1970s (see Figure 1 and Figure 2) The archive contains up to 10,000 paper documents produced since 1980: correspondence between base committees to the provincial headquarters in Chota, communication with provincial and regional federations and foreign organizations, minutes of internal assemblies and public congresses, drafts and originals of public statements, diagnostic reports on social problems, and detailed complaints and resolution cases of customary-law disputes. Since 2022, I have been working with the Federation on two different projects2 and, together with María Rodríguez, Alejandro Diez, and Paulo Drinot, I am now collaborating to preserve and inventory this archive, thanks to generous funding from UCLA’s Modern Endangered Archives Programme (see Figure 3).

This investment in documentation becomes particularly visible in the “living archive” safeguarded by the Federación Provincial de Rondas Campesinas de Chota, which traces the organisation’s history since its emergence in the late 1970s (see Figure 1 and Figure 2) The archive contains up to 10,000 paper documents produced since 1980: correspondence between base committees to the provincial headquarters in Chota, communication with provincial and regional federations and foreign organizations, minutes of internal assemblies and public congresses, drafts and originals of public statements, diagnostic reports on social problems, and detailed complaints and resolution cases of customary-law disputes. Since 2022, I have been working with the Federation on two different projects2 and, together with María Rodríguez, Alejandro Diez, and Paulo Drinot, I am now collaborating to preserve and inventory this archive, thanks to generous funding from UCLA’s Modern Endangered Archives Programme (see Figure 3).

2. My engagement with the Federation’s archive began in 2022 within the framework of the project 2022-E-0001, “Organización política y cultura visual en el Perú: (auto)representación, nuevas subjetividades sociales y luchas políticas (1968–1992),” funded by the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Figure 3. Team working in the preservation of the archive. Author’s photographs, November 2025.

I call this collection a “living archive” because it is the product of an on-going, open-ended endeavour. Rather than safeguarding what Stuart Hall describes as ‘tradition’ –“which is seen to function like the prison-house of the past” (2001, p. 89)– the archive testifies to the historical assembling of the rondas as a modern institution, as well as to political becomings in spaces supposedly marginal to state power. Crucially, the archive is not external to the organisation’s present life as it remains embedded in the ronda’s own vernacular bureaucracy, actively expanded and mobilised.

As I begin my engagement with this archive, my interest lies less in the “fixed” contents of its documents than in the social life they mediate. If they are the rondas’ skin and bones, how do they animate the organization’s vital functions? What forms of political life do they enable, constrain or stabilise? Attending to the care with which ronderos produce, circulate, safeguard, and sometimes treasure these written records draws attention to documentation itself as a site of political labour. In what follows, I will share some preliminary reflections on the political becomings of rondas campesinas as a hybrid organization, and how they have shaped the emergence of the rondero as key peasant political subject. In this process, the document as a genre and the archive as practice have served as critical tools for building a form of authority that is simultaneously legible to the state and persistently in tension with it.

As I begin my engagement with this archive, my interest lies less in the “fixed” contents of its documents than in the social life they mediate. If they are the rondas’ skin and bones, how do they animate the organization’s vital functions? What forms of political life do they enable, constrain or stabilise? Attending to the care with which ronderos produce, circulate, safeguard, and sometimes treasure these written records draws attention to documentation itself as a site of political labour. In what follows, I will share some preliminary reflections on the political becomings of rondas campesinas as a hybrid organization, and how they have shaped the emergence of the rondero as key peasant political subject. In this process, the document as a genre and the archive as practice have served as critical tools for building a form of authority that is simultaneously legible to the state and persistently in tension with it.

**

Let’s return briefly to the very first days of the rondas campesinas’ emergence.

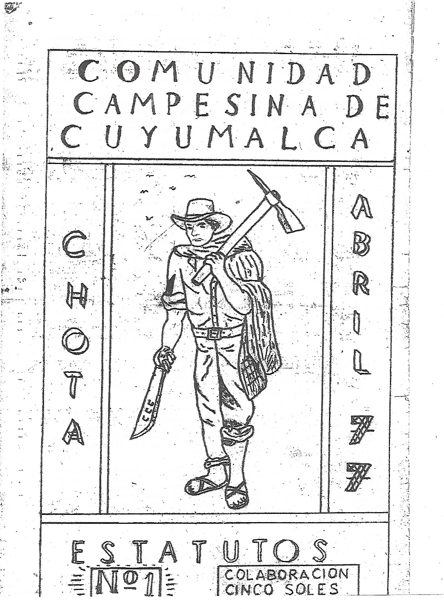

Cattle rustling by abigeos had become a common occurrence, but when thieves broke into the school of Cuyumalca, not once but eight times, villagers’ outrage reached a breaking point. Something had to be done. At the schoolyard meeting, Régulo Oblitas, one of the villagers who held the position of teniente gobernador,3 insisted on an idea he had previously proposed without success: organising a ronda, a form of night patrol he had learned about during his experience working as a seasonal labourer in the coastal hacienda of Tumán. This time, the assembly was attended not only by peasants but also by the schoolteacher and police officers, whose presence proved decisive in pressuring villagers –many of whom were fearful of abigeos’ retaliation – to accept the proposal. The villagers agreed, and that very night the first ronda of ten men patrolled the village. They are now remembered as the founders of the rondas campesinas.

Cattle rustling by abigeos had become a common occurrence, but when thieves broke into the school of Cuyumalca, not once but eight times, villagers’ outrage reached a breaking point. Something had to be done. At the schoolyard meeting, Régulo Oblitas, one of the villagers who held the position of teniente gobernador,3 insisted on an idea he had previously proposed without success: organising a ronda, a form of night patrol he had learned about during his experience working as a seasonal labourer in the coastal hacienda of Tumán. This time, the assembly was attended not only by peasants but also by the schoolteacher and police officers, whose presence proved decisive in pressuring villagers –many of whom were fearful of abigeos’ retaliation – to accept the proposal. The villagers agreed, and that very night the first ronda of ten men patrolled the village. They are now remembered as the founders of the rondas campesinas.

3. A state-appointed local authority responsible for minor administration, maintaining order, and serving as the state’s representative in rural communities.

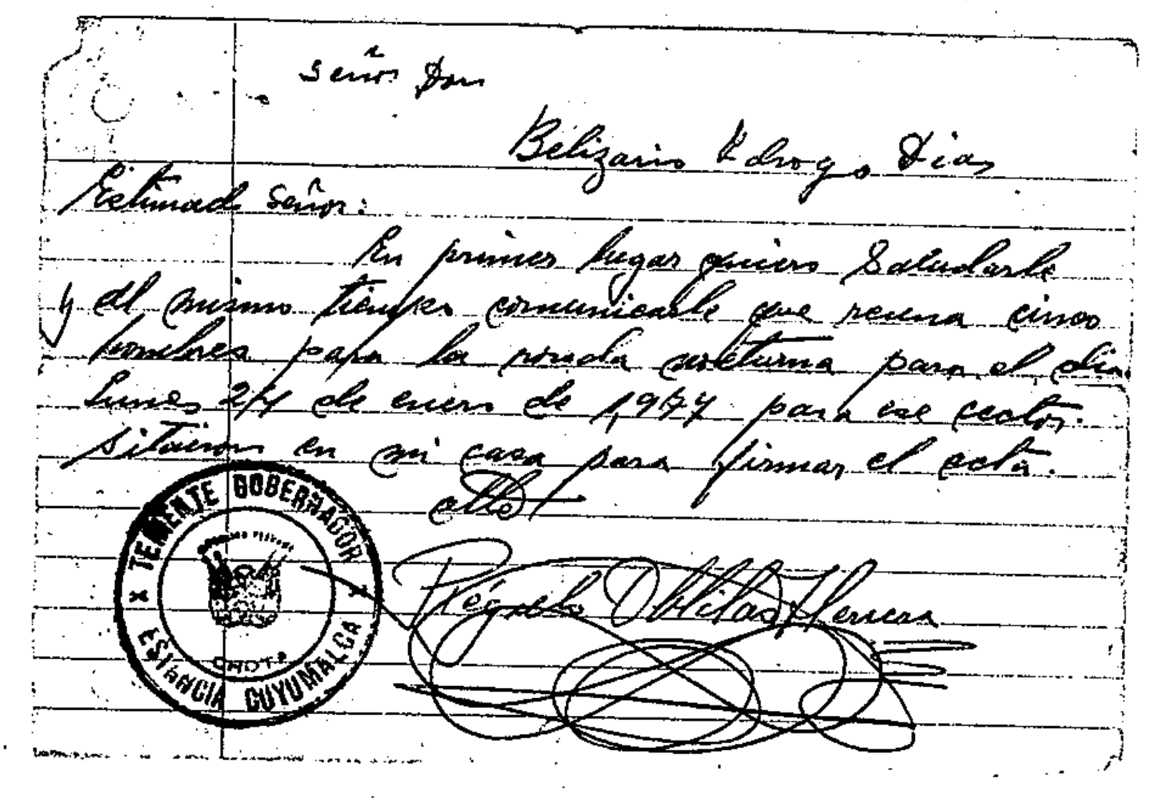

This first assembly, held on December 29, 1976, was recorded in the minutes. The following morning, Oblitas informed the provincial sub-prefect in writing and requested authorization. The authorization arrived on January 6, and this document quickly took on an important role: Oblitas and other leaders even made photocopies and distributed them among the peasants as a way of urging their participation. In addition, Oblitas issued written summons calling on peasants to join the patrols (see Figure 4), and identification cards were distributed to identify the members. A month later, another assembly –again recorded in the minutes– further formalised the organisation: a governing board was elected, certificates were issued to the patrol leaders, and a registry of members was established.

4. The reconstruction of this history draws on ethnographic accounts of the rondas campesinas, particularly those by Orin Starn (1999) and John Gitlitz (2013). Starn shows how the foundation story preserved in popular memory has framed the rondas as a purely anti-official village initiative, thereby concealing its mixed origins.

Figure 4. Régulo Oblitas urges Belizario Idrogo to gather five men for a night patrol for January 24, 1977. Personal archive of Óscar Sánchez.

Minutes, identification cards, authorizations, letters, and members’ registries: from its inception in Cuyumalca, documents, things made of paper, have mediated the relationship between people, norms, temporalities, social hierarchies, and collective problems. They scaffolded the emergence of the rondas as a vernacular institution. This documentary centrality is striking given that, at the time, nearly half of Peru’s rural population was illiterate.5 Yet this reflects a broader pattern observed in rural Peru, where writing has long functioned as a key political and legal technology. Salomon and Niño-Murcia's (2011) ethnography of writing culture in Tupiscocha, a peasant community in Peru’s central highlands, shows that interventions of public rural schooling and literacy represent a recent overlay on a much older literate order shaped by legal genres. For centuries, peasant communities and their ancestors have engaged with legal writing as a crucial arena for securing livelihood and asserting citizenship. Historian Ponciano del Pino (2024) describes a “document-focused culture” emerging from often unending legal procedures that mobilised entire communities and sent local autoridades journeying from office to office (Del Pino Huamán, 2024, p. 622). Javier Puente (2023) further argues that peasant communities and the Peruvian state have mutually constituted each other through writing, a form “political literacy”. Yet such perspectives on documents and the written word not as “a neutral purveyors of discourse, but as mediators” (Hull, 2012, p. 253) remain relatively scarce. As a result, peasant engagements with writing and the law have often remained analytically invisible, reinforcing common-sense assumptions that cast peasants as dominated by oral culture and marginal to the law. As Matthew Hull (2012) shows, within anthropology documents have frequently been treated mere emblems of government bureaucratic authority or as technologies deployed to govern populations, rather than as instruments of social, political, and institutional life that operate beyond –and sometimes against– the state.

5.

According the 1972 census, 51.9 % of the rural population were illiterate; among women, that rate rose to 69.2 %.

Like other community archives, the Federation’s challenges the idea of archives as “as long-standing bastions of governmental and bureaucratic power, authority, and control” (Poole, 2020, p. 658). At the same time, documents and archives are also a way how rondas build bureaucratic authority for themselves. On the one hand, documents function as epistemic objects: through their “know-show” function (Gitelman, 2014) they help to stabilise truth. Salomon & Niño-Murcia describes villager’s “romance” with writing in the way every collective act culminates in a constancia, valued for its capacity to connote durable knowledge – “a defence against errors, falsehoods and forgetting” (2011, p. 25). Similarly, when ronderos file a complaint, they transform the account into a fact by articulating it in a recognised written language on a specific medium. From there, the document lives a particular kind of life: it enters a procedural chain through which rondas resolve conflicts and administer justice: that is, it is recorded in the complaint book, discussed in assembly, and followed by investigation and sanction. The record of this entire process is archived, building what might be described as a folk-legal justice process from beginning to end.

More interestingly, documents also operate as props or technologies in the theatre of governing (Gitelman, 2014; Hull, 2012). Their social life becomes visible in how ronderos stage architectures of authority. Whether placed on a desk or held in hand, the presence of a notebook often signals who governs (see Figure 5). This is visible in the Federation headquarters, but also when file complaints or assemblies are convened in peasant houses or communal centres. Once again, the document's eventual journey into the archive is itself part of this theatre: authority is bound up with who stores documents, where they are stored, and who control access to them. It is not so much, as Lisa Gitelman (2014, p. 5) reminds us, that bureaucracies employ documents as that “they are partly constructed by and out of them” (the emphasis is mine). In this sense, documents are not mere sites of record but constitutive of a bureaucratic order, encompassing “rules, ideologies, knowledges, practices, subjectivities, objects, outcomes, and even the organizations themselves” (Hull, 2012, p. 253).

More interestingly, documents also operate as props or technologies in the theatre of governing (Gitelman, 2014; Hull, 2012). Their social life becomes visible in how ronderos stage architectures of authority. Whether placed on a desk or held in hand, the presence of a notebook often signals who governs (see Figure 5). This is visible in the Federation headquarters, but also when file complaints or assemblies are convened in peasant houses or communal centres. Once again, the document's eventual journey into the archive is itself part of this theatre: authority is bound up with who stores documents, where they are stored, and who control access to them. It is not so much, as Lisa Gitelman (2014, p. 5) reminds us, that bureaucracies employ documents as that “they are partly constructed by and out of them” (the emphasis is mine). In this sense, documents are not mere sites of record but constitutive of a bureaucratic order, encompassing “rules, ideologies, knowledges, practices, subjectivities, objects, outcomes, and even the organizations themselves” (Hull, 2012, p. 253).

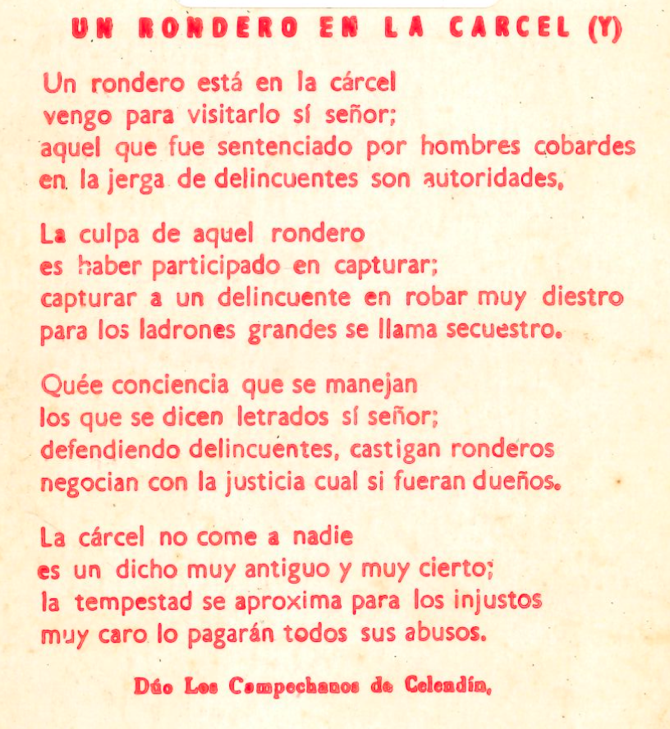

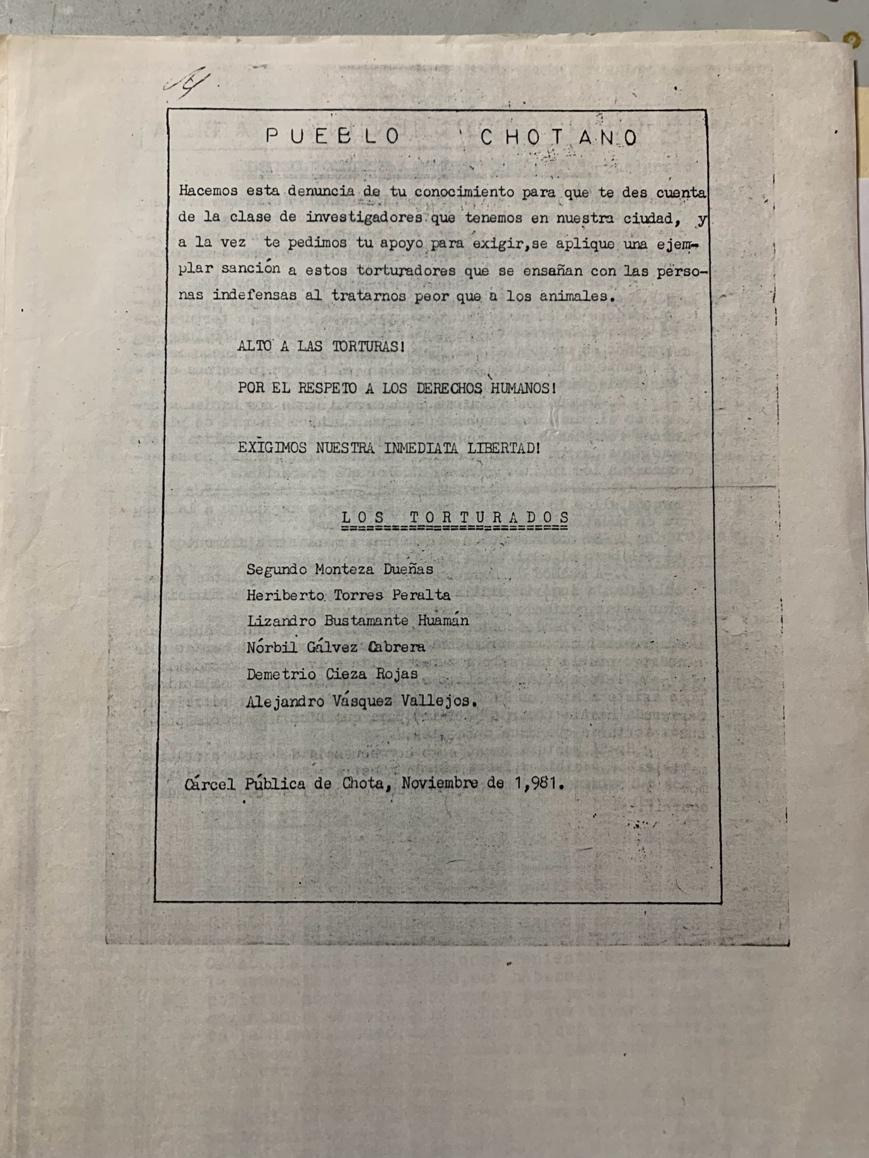

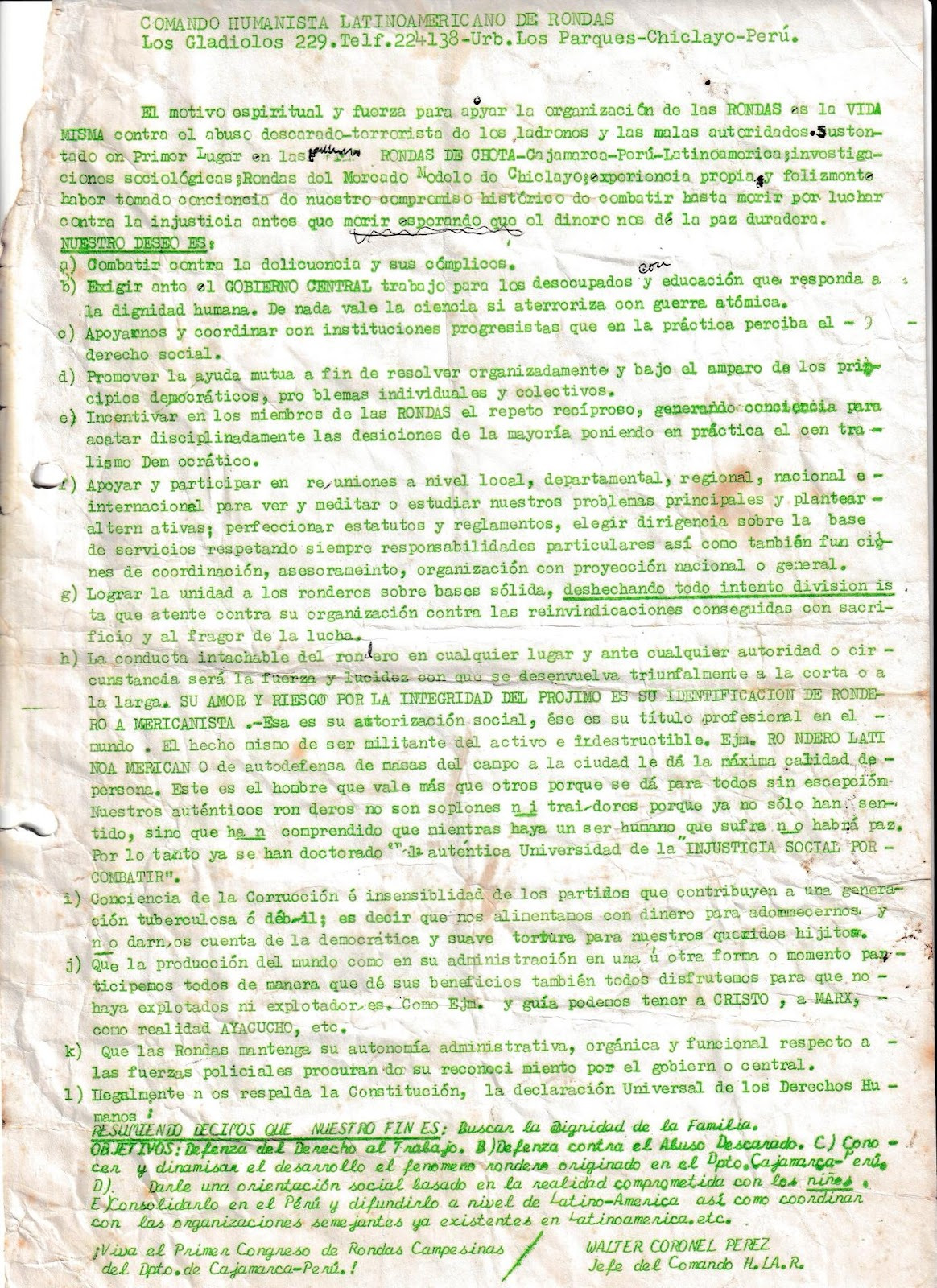

But if documents exude the authority of the institutions they represent, what kind of authority are we talking about in the case of the rondas campesinas? This question is especially salient during their first decade, when the rondas lacked official recognition and were being subject to active prosecution by the state (see Figure 6 and Figure 7). I argue that the mimicry and borrowing of bureaucratic mechanisms with which peasants were already familiar –through their prior engagements with the state and other institutions– became a central component of how the rondas constructed legitimate meanings of power and authority.

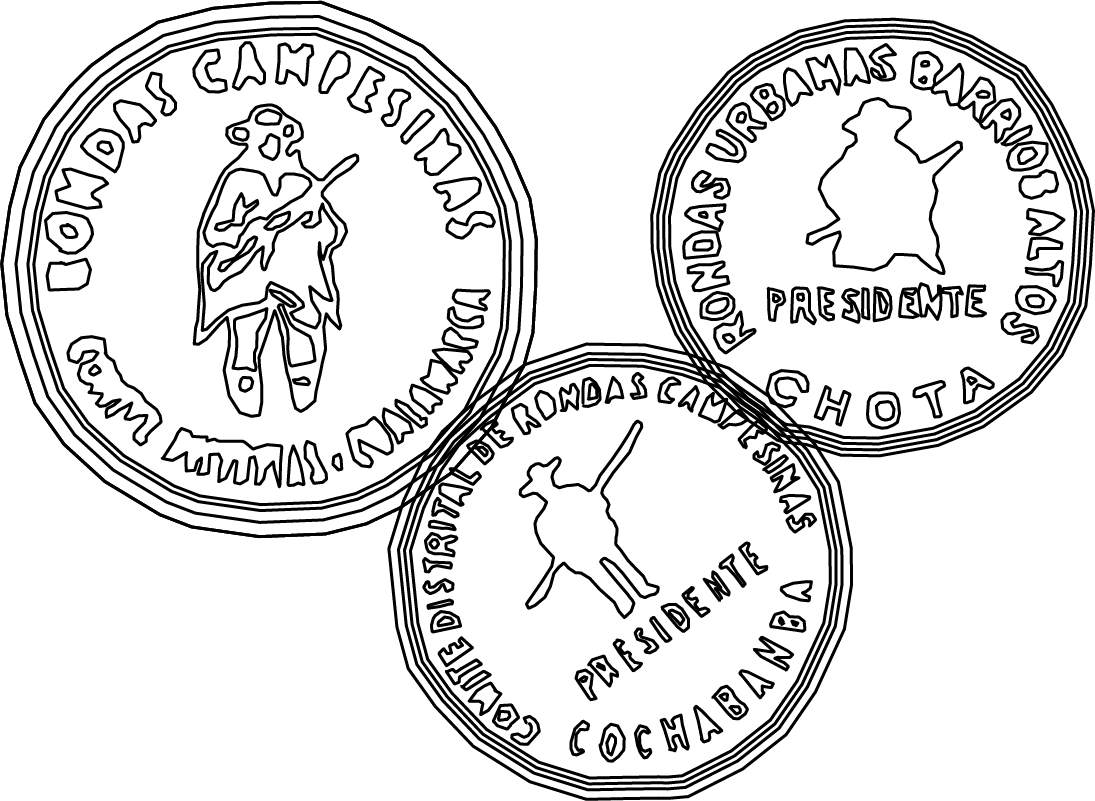

This practice of mimicry can be understood both as a way of instantiating the state and as a way of creolising state practices to affirm the constitution of autonomous folk-legal institutions. As Salomon & Niño-Murcia (2011, p. 27) notes in the case of Tupicocha, the writing of unofficial ayllu books can be considered as a state practice operating at the level of customary law: “the emulation of state norms within the intravillage conduct of Andean institutions, even when no official demands it, is marginal citizens’ manner of approaching state power.” While the same could be argued for the case of rondas campesinas, we see them creolising codes, languages and rationalities of pre-existing bureaucracies to dispute state authority (see Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). As Starn (1999) observes, the rondas “enchantment with the seal, the law, and the memo” reveals how official administrative rituals became integral to ronda justice-making. This borrowing of legal bureaucracy was not a simple imitation, but part of a broader process of invention through which the rondas developed an original mode of conflict resolution. In this sense, ronderos can be thought as subaltern bureaucrats, not as the indigenous or racially marked civil servants of postcolonial states that Radcliffe & Webb (2015) refer to, but insofar as they construct a bureaucracy that negotiates an ambiguous position: exercising autonomy while simultaneously seeking recognition from a historically exclusionary state bound up with hegemonic norms of whiteness.

This practice of mimicry can be understood both as a way of instantiating the state and as a way of creolising state practices to affirm the constitution of autonomous folk-legal institutions. As Salomon & Niño-Murcia (2011, p. 27) notes in the case of Tupicocha, the writing of unofficial ayllu books can be considered as a state practice operating at the level of customary law: “the emulation of state norms within the intravillage conduct of Andean institutions, even when no official demands it, is marginal citizens’ manner of approaching state power.” While the same could be argued for the case of rondas campesinas, we see them creolising codes, languages and rationalities of pre-existing bureaucracies to dispute state authority (see Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). As Starn (1999) observes, the rondas “enchantment with the seal, the law, and the memo” reveals how official administrative rituals became integral to ronda justice-making. This borrowing of legal bureaucracy was not a simple imitation, but part of a broader process of invention through which the rondas developed an original mode of conflict resolution. In this sense, ronderos can be thought as subaltern bureaucrats, not as the indigenous or racially marked civil servants of postcolonial states that Radcliffe & Webb (2015) refer to, but insofar as they construct a bureaucracy that negotiates an ambiguous position: exercising autonomy while simultaneously seeking recognition from a historically exclusionary state bound up with hegemonic norms of whiteness.

This brings me back, in closing, to the hybrid character of rondas campesinas as political organisations and their constitutive entanglement with the state. Far from being the legacy of an imagined “ancestral past”, rondas were created by actors integrated into economic and political dynamics spanning rural and urban worlds. Many had been hacienda peons and seasonal labourers in coastal, more “modern” regions, where some encountered and embraced radical political currents. As noted earlier, the Maoist party Patria Roja played a significative role in the early constitution of the rondas campesinas, particularly through Daniel Idrogo –a young Cuyumalquino studying law on the coast–, who returned to Chota and was instrumental in expanding the organisation’s reach and functions. To a lesser extent, the centrist APRA (Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana) also had an influence in the rondas’ expansion: while the party’s leader in Chota opposed their involvement in justice-making, he nonetheless recognised their growing popularity and attempted to outmanoeuvre Patria Roja by turning the organisation into a party stronghold. The rondas’ growth and consolidation were further shaped by the involvement of the Church and various NGOs, which helped channel funding and expertise. Precisely due to these involvements, the rondas have historically insisted on their “independence”, transforming autonomy into a guiding political principle that structured their engagements with parties, the state and other institutions.

Furthermore, these actors maintained long-standing and often tense relationships with the state –at times representing it, as tenientes gobernadores, or having been trained by it, as former conscripts. The rondas thus did not emerge as a response to the state’s absence, but rather to the exclusionary ways in which the state was present in rural areas. Therefore, from the outset, their commitment was not to establish themselves as anti-state institutions, but rather to claim legitimacy as auténticos defensores de la ley (authentic defenders of the law). In doing so, they defy romanticized views of indigenous and peasant politics, demonstrating how the defence of autonomy and sovereignty can coexist with an active desire to engage, appropriate, and contest the authority of the state and other institutions (see Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Furthermore, these actors maintained long-standing and often tense relationships with the state –at times representing it, as tenientes gobernadores, or having been trained by it, as former conscripts. The rondas thus did not emerge as a response to the state’s absence, but rather to the exclusionary ways in which the state was present in rural areas. Therefore, from the outset, their commitment was not to establish themselves as anti-state institutions, but rather to claim legitimacy as auténticos defensores de la ley (authentic defenders of the law). In doing so, they defy romanticized views of indigenous and peasant politics, demonstrating how the defence of autonomy and sovereignty can coexist with an active desire to engage, appropriate, and contest the authority of the state and other institutions (see Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Rondas campesinas complicate conventional understandings of the margins of the state, revealing them as sites of “radical possibility” (McEwan, 2005) in which social actors engage in “acts of citizenship” –those deeds through which people constitute themselves as political subjects not by conforming to the dominant, often orientalising models of citizenship, but by challenging and reworking them (Isin & Nielsen, 2008, p. 2). The counterpublics forged through the rondas campesinas functioned as laboratories of political experimentation and subject formation. Becoming a rondero unsettled their historically subaltern position as indigenous peasants, involving what one rondero described to John Gitlitz (2013) as a process of “raising their heads high”: an embodied transformation of their political being enacted through transformed relationships to the law, the state, and mestizo and urban society. These acts of citizenship challenge the state as the sole locus of authority for granting rights, while simultaneously pushing the state to widen their exclusionary frameworks. The Federation’s archive thus stands as a privilege witness to this formation of political power from below and as a repository of documents whose circulation did not merely record ronderos as political subjects but actively mediated their production. In doing so, it traces how intercontinental political imaginaries travelled and were locally translated into everyday forms of governance: sedimented in paper, ink, and the routines of administration.

References

- Del Pino Huamán, P. (2024). Communal Minute Books: Writing, Ethnography, and History of the War in Peru in the 1980s. Journal of Social History, 57(4), 619–639. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shad076

-

Gitelman, L. (2014). Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents. Durham: Duke University Press.

-

Gitlitz, J. (2013). Administrando justicia al margen del Estado. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

-

Hall, S. (2001). Constituting an archive. Third Text, 15(54), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528820108576903

-

Hull, M. (2012). Document and Bureacracy. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41, 251–267.

-

Isin, E. F., & Nielsen, G. M. (2008). Acts of citizenship. London & New York: Zed books.

-

Laos, A., Paredes, P., & Rodríguez, E. (2003). Rondando por nuestra ley: La exitosa experiencia de incidencia política y cabildeo de la Ley de Rondas Campesinas. Lima: Asociación Servicios Educativos Rurales.

-

McEwan, C. (2005). New spaces of citizenship? Rethinking gendered participation and empowerment in South Africa. Political Geography, 24(8), 969–991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.05.001

-

Poole, A. H. (2020). The information work of community archives: A systematic literature review. Journal of Documentation, 76(3), 657–687. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-07-2019-0140

-

Puente, J. (2023). The Rural State: Making Comunidades, Campesinos, and Conflict in Peru’s Central Sierra. Austin: University of Texas Press. https://doi.org/10.7560/326282

-

Radcliffe, S. A., & Webb, A. J. (2015). Subaltern Bureaucrats and Postcolonial Rule: Indigenous Professional Registers of Engagement with the Chilean State. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 57(1), 248–273. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417514000668

-

Salomon, F., & Niño-Murcia, M. (2011). The Lettered Mountain. A Peruvian Village’s Way with Writing. Durham: Duke University Press.

-

Sánchez, O. (1992). La Justicia Campesina. Cajamarca: Federación Provincial de Rondas Campesinas de Chota.

- Starn, O. (1999). Nightwatch. The Politics of Protest in the Peruvian Andes. Durham: Duke University Press.

Sandra Rodríguez Castañeda

Sandra W Rodríguez Castañeda is a Peruvian anthropologist whose works sits at the intersection of social reproduction, political ecology and peasant politics, integrating creative and audiovisual methods in research and dissemination. She is currently a PhD student at the Institute of the Americas, University College London.

Sandra W Rodríguez Castañeda is a Peruvian anthropologist whose works sits at the intersection of social reproduction, political ecology and peasant politics, integrating creative and audiovisual methods in research and dissemination. She is currently a PhD student at the Institute of the Americas, University College London.