Gal Kirn

Two Liberation Vignettes:

Partisan and Socialist Internationalism in Yugoslavia, Palestinian comrades in arms

Tonight I saw your palm,

how it got squeezed in the firm fist

in the darkness of the Ljubljana streets.

And you know of what I thought, poet-Partisan?

If only my poem were like your palm,

all soft and tender like the cherry blossom in spring

and that it were as resistant as your fist,

whenever you witness the fascist parade.

Matej Bor, verse from Love in Storm (1942)

In the decades following 1989 a certain “left-wing melancholia” gradually inhabited the waning political site of internationalist, non-aligned and Tricontinental legacy. As Enzo Traverso (2017) potently demonstrated - weaving together intellectual, political and cultural sources of the twentieth century - the left first had to tackle the defeat in order to move forward. I believe that time has come both to move beyond cultivation of defeat, and to announce a final end of “end of history”, realigning and re-imagining past and present solidarities that run across Tricontinental space and time. I have been now for a long while working on the intersections of liberation and antifascist politics and art in the (post)Yugoslav context and beyond. Most notably, I have been interested in the practices, (counter)archival materials, and heterogeneous ways in which emancipatory traces persist despite mainstream silencing of the past or conservative demonising of revolutionary events. Identifying and locating emancipatory fragments hidden, forgotten, and scattered—sometimes deep in oceans—has been a matter of urgency, the fundamental step toward defragmenting the material so that it can also intervene in present nationalist and imperial archives. I have argued that there is something about these emancipatory fragments that keeps returning despite the grim present—something I call “partisan surplus” (Kirn, 2019)1—which inspires us beyond national borders and the spatio-temporal limits of our own positionality.

1. My book Partisan Counter Archive is not a pioneering research in counter-archival memory/history making; I contribute to and align my work with other creative and critical attempts around 'counter-visuality' (Mirzoeff) and 'potential history' (Azoulay) to dialectical images and the 'tradition of the oppressed' (Benjamin) to name a few.

There is, however, an additional obstacle to returning to the past that I would like to address here: even those sympathetic to specific anticolonial and antifascist struggles often interpret the importance of such struggles within a “national” and sovereigntist frame. For example, coming from Ljubljana, (post)Yugoslavia, the People’s Liberation Struggle (1941–1945)—if defended at all—has been reduced to its national dimension. We are told to see it as the sovereign cornerstone of the Slovenian nation-state rather than to speak of its revolutionary, intersectional, and internationalist dimensions. Forget about socialism, about its subsequent contributions to anticolonial, non-aligned and Tricontinental modernities; forget about Yugoslavia—celebrate Slovenia and capitalist realism instead. Some even bitterly suggest that any return to the partisan, liberation, and revolutionary past—especially the internationalist solidarity—should be re-evaluated, since seemingly the last remnants of this imaginary, such as Kurdish Rojava and the Palestinian liberation forces, seem to be encountering utter horror and genocide in this new era of imperialism.

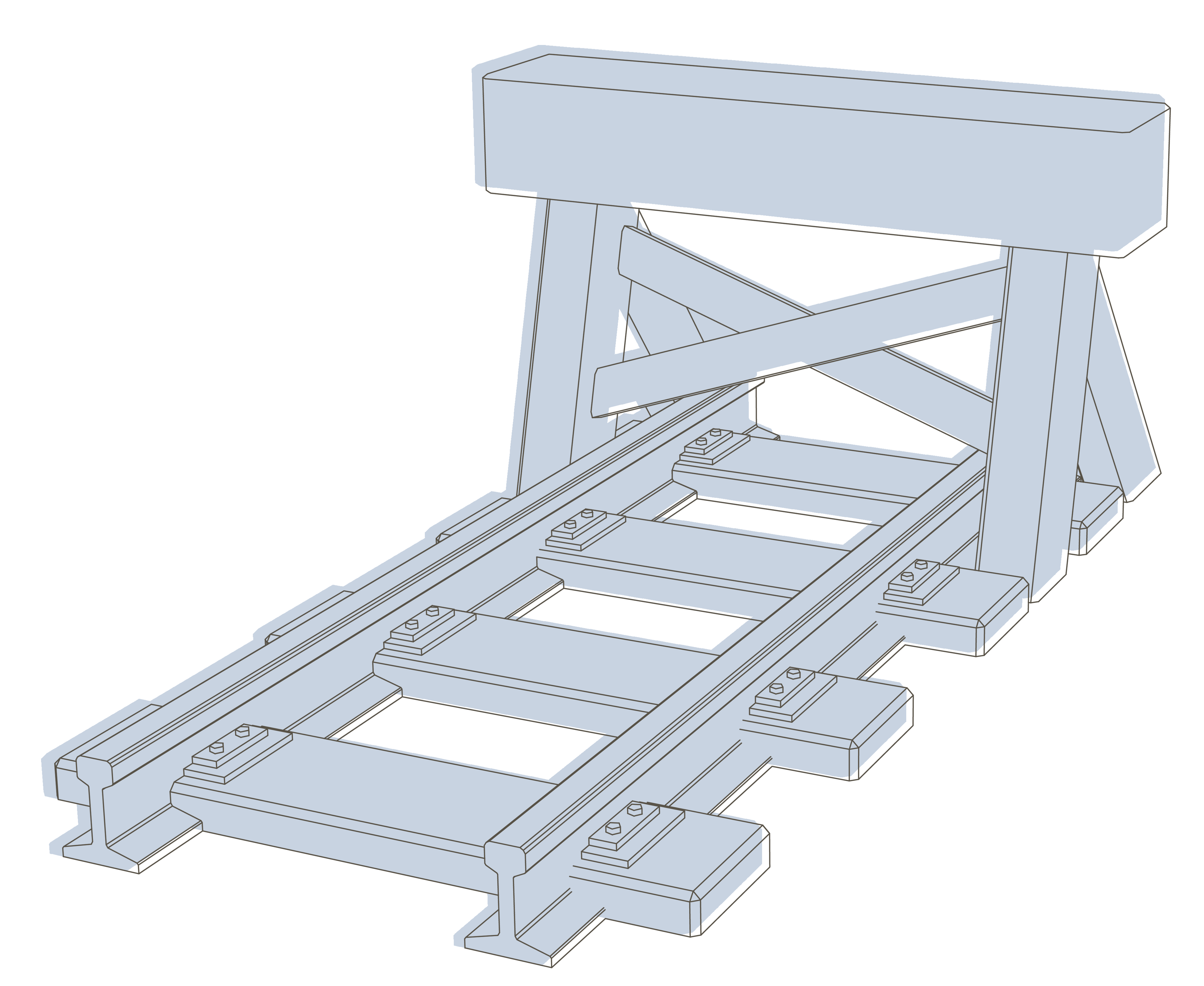

Looking back from this engaged positionality and in light of the current situation in Gaza, I have decided to present in this modest contribution two vignettes that highlight the vital internationalist—antifascist and socialist—dimension of Yugoslav modernity. The first recalls the real history of two Palestinian fighters, Yunis and Krim, who joined the Yugoslav Partisans in World War II and whose contributions and spirit echoed in the famous lines of partisan poet Matej Bor (Previharimo Viharje, 1942). The second comes from 1948, when Yugoslavia—with its split with Stalin, and isolation from East and West—embarked on its own internationalist road to socialist independence and was helped by international youth brigades. This moment is recuperated in the recent film Sunny Railways (2023) by Nika Autor, whose camera also follows one young Palestinian socialist woman who helped build the railway from Šamac to Sarajevo in just a few months (242 km). This is what internationalism and solidarity meant and how they were performed—beyond words and protests.

Looking back from this engaged positionality and in light of the current situation in Gaza, I have decided to present in this modest contribution two vignettes that highlight the vital internationalist—antifascist and socialist—dimension of Yugoslav modernity. The first recalls the real history of two Palestinian fighters, Yunis and Krim, who joined the Yugoslav Partisans in World War II and whose contributions and spirit echoed in the famous lines of partisan poet Matej Bor (Previharimo Viharje, 1942). The second comes from 1948, when Yugoslavia—with its split with Stalin, and isolation from East and West—embarked on its own internationalist road to socialist independence and was helped by international youth brigades. This moment is recuperated in the recent film Sunny Railways (2023) by Nika Autor, whose camera also follows one young Palestinian socialist woman who helped build the railway from Šamac to Sarajevo in just a few months (242 km). This is what internationalism and solidarity meant and how they were performed—beyond words and protests.

Partisan Internationalism

First, the story of two Palestinain fighters. In our attempt to de-nationalise the partisan struggle, it needs to be said that it was only the political and military formation of the Yugoslav People's Liberation Struggle that was open to all nations, nationalities, religions, while all others were strictly organised according to ethnic belonging (Ustasha Croats, Slovene Home Guards, Serbian Chetniks) and all subjugated under the racist and supermatist leadership of foreign fascist occupation. Furthermore within Yugoslav partisan units there were also women, Jews, and foreign antifascists, from Eastern countries but also thousands of Italian antifascists (Garibaldists) and German antifascists (Thällman battalion) who fought alongside Yugoslavs. It is no coincidence that the main slogans of the Yugoslav liberation struggle were 'Death to fascism, freedom to people' and 'freedom has no nationality.'

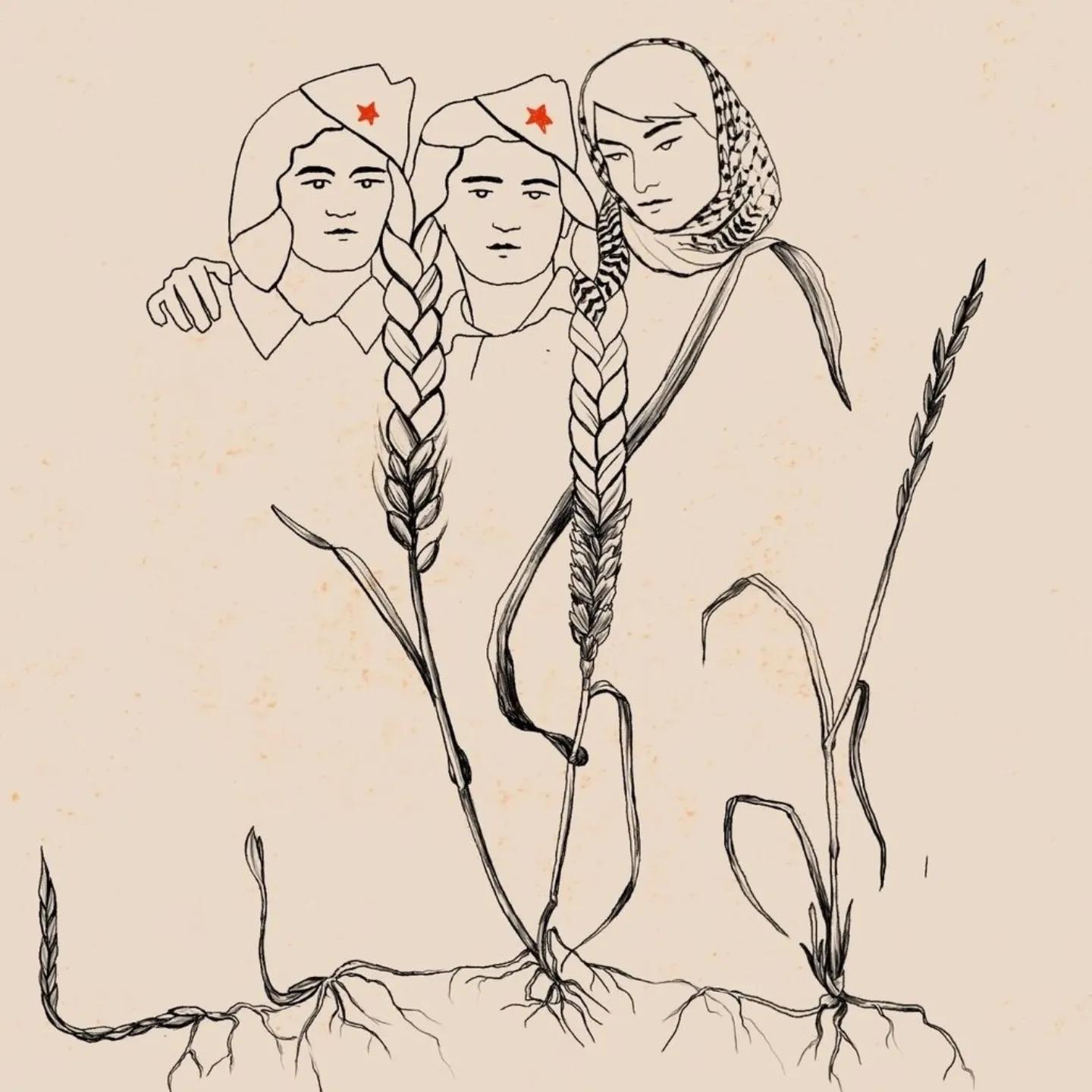

Let us zoom in two fighters, Mehmed Junis and Abdul E. Krim, who were imprisoned in Crete and then escaped from the German train that en route to a concentration camp. They accidentally met partisans in the forest near Celje and decided to join their fight. Needless to say, there were not many Palestinians fighting within the Yugoslav PLS; despite this, one major poetic event meant that Junis and Krim's names and internationalist spirit were not forgotten. It was in the first major avantgardist poetry collection in the winter of 1941/42 that Matej Bor paid hommage to Junis and Krim, titling the poem with their names. As Miklavž Komelj lucidly argued in his book How to Think Partisan Art (2009), Matej Bor not only mentioned their names and recounted their fight, but also defined them as 'Slovenian partisans.' The latter is not a person that is marked by national belonging, but someone who is struggling for liberation on that particular territory. Matej Bor became one of the major partisan poets and his collection— Previharimo Viharje (Overstorming storms)—was printed in the thousands, both in occupied Ljubljana and, later on during the war. –in the winter of 1941/1942. Also important to note is the massive importance partisan art had in the process of social transformation;in the four years of struggle more than 40.000 poems were written, mostly coming from anonymous partisans, and often those that had just learned to write and read.

The poem about and for Junis and Krim starts with the inscription/hommage: Arabskima tovarišema Junisu in Krimu, ki sta padla kot slovenska partizana na Štajerskem v Jeseni 1941 / To Arabic comrades: Junis and Krim that fell like Slovenian partisans in the region of Štajerska in the late autumn of 1941.

The poem first describes their escape from the deadly train-wagons that 'carry echoes, reflections of former people', and follows their path into the forests as a site of refuge. The poem refers to their mother’s voice calling for them from the distance and being woven with their encounter with fellow partisans and embracing of their displacement and new political belonging. In the second part, these forests become the site of political subjectivation. Krim and Junis become 'Slovenian partisans in the scent of pines, spruces, moss and ferns on the sunny shores they travelled'. This personal-political transformation carries a strategic shift that helped to redefine the partisan criterion of brotherhood. The central cohesive bond is not blood/ethnic belonging but solidarity established in the fight for the collective cause, for liberation of all.

Yet at the same time, this political subjectivation does not erase the differences: the poem treats with utmost respect differences within the tradition of the oppressed. You might whisper 'Alah, Alah, when you and comrades went into attacks', through struggle and the conversations real comradeship emerged, in the evenings

the dreamy songs of spruces, clouds and autumn grasses

were tempered only by the whisper of conversation. Janez said:

"Hitler in kapital!" and he pumped his fist in the air.

"Hitler and capital!" Krim laughed.

"Our will be victory and future! 'tis so, Francak?"

All, you understood all, fist, eyes, hands:

because the language knows the heart also without words.

Until the last moment they fought bravely, besieged with their comrades in the barn by fascists who also lit fire.

Junis, Krim ... the voice cried all night

from distance...

Junis, Krim!

The storm has cast you on the shore ...

And us?

We sail on.

The voice of internationalism is woven within many poems and songs. A little before Matej Bor's publication in then-Slovenia, autumn of 1941 already saw the first liberated territory of Europe in Užice's republic (today's Serbia) that already established political and cultural institutions, and also published the first print of partisan poems and songs called Antifašističke pesme / Antifascist Poems on 7 November 1941, which also contained international songs of resistance. The Yugoslav People’s Liberation Struggle was a major political event and, alongside liberation struggles in Greece and Albania, it succeeded in liberating its territories by relying on its own forces. Revolutionary, federal and socially oriented Yugoslavia was already announced in 1943 by partisan delegations coming from all regions – without any confirmation from the Allies, who at that point still – Stalin included – supported the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its government in exile, stationed in London, with its military formation Chetniks openly collaborating with fascists.

Socialist Internationalism

The second archival journey is a vignette from after the World War 2, which saw Yugoslavia continue its own path of socialism and ‘internationalism.' I argue elsewhere that especially after the split with Stalin in 1948, Yugoslavia becomes one of the key allies in non-aligned and anticolonial struggle that helps shaping also Tricontinental spirit. I take a beautiful hommage/wommage by contemporary film-maker Nika Autor from post-Yugoslav context. She works on archival material of the socialist and partisan legacy, while also making sure that documentary and political dimensions are not presented at the expense of aesthetic style and poetic devices. Her work skilfully navigates between the archives of the past—between socialism and partially realized utopias—while also bringing us to the midst of the Balkan dystopia today, to abandoned places where ethnic wars took place, and to the Balkan route, where migrants encounter horrific circumstances such as border control, police violence, the absence of official infrastructure, and also take us on a journey through the underground infrastructure of migrants.

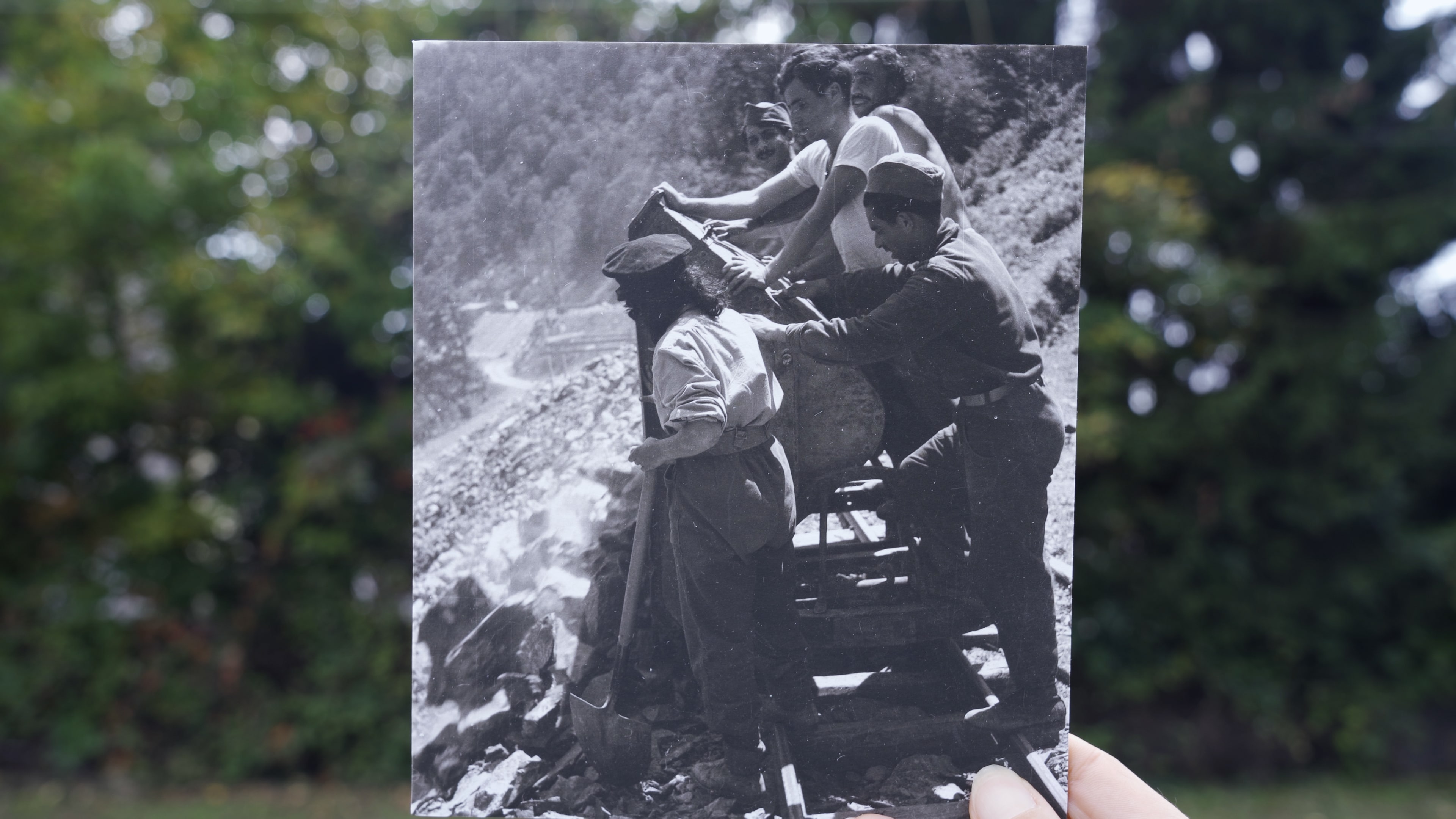

Here I want to delve into her last film, Newsreel 242, which also goes by the name Sunny Railways (2023). This film investigates the early postwar period of Yugoslavia after the fascist occupation, which left much of the basic infrastructure destroyed and in need of rebuilding. It was in 1947 that international youth (brigades) met with Yugoslav youth volunteers and built 242 km of railroad between Sarajevo and Šamac in a mere matter of months. The archival footage is accompanied by an off voice that travels through past and present landscapes and self-reflects about what it was that guided the youth in their internationalist spirit and solidarity. In what way can the bodies of all those working on the railroad express not only the idea of a socialist utopia, but its material realization? There is, however, a constant jump between the time of the present, the dystopian war-scarred landscape and the ethnic bodies of today, and the bygone time of socialist internationalism.

What Nika Autor engages with at length is the representation of internationalist spirit, something yet again that cannot be reduced to state propaganda, or to forced and manipulated labour. Railroad construction here pointed to the multiple conceptions of the future. Both camera and storyline dwell on the image of one Palestinian woman who is working together with two other comrades. We see her only from side-on, but we cannot see her face or hear her voice (see image above). Spectators might speculate as to where she ended up a year later, during the 1948 Nakba, and whether and how she was involved in Palestinian anticolonial struggle. It evokes a dimension of past international solidarity with the Palestinian anticolonial struggle, of which Yugoslavia was one of the great supporters. Furthermore, the image of antifascist and anticolonial struggle is not about violence, but it has always been internally linked to the image of peace and social justice. The film shows us people, young and old, happily working and building a project, a new railroad that symbolizes peace and sisterhood with other nations and people.

In the second part of the film, we come to the real desert of the postsocialist transition. This time we find the landscape empty once more; there are practically no people, which strongly echoes Pavle Levi, who argues: 'What is missing are, of course, the people (Deleuze) ... People – yes, but... not only the living. The dead, too, are missing! There is a manifest absence of human bodies, all human bodies, in these films. Bodies engaged in various activities, behaviours, and ges-tures, whether mundane or extraordinary.'2 Nature seems to take some revenge on people, their wars, and horrific consequences, nature overgrows the railway tracks. The images and archival footage of new wars and genocide are absent. We might wonder whether the image of ethnic wars is absent because it bears no emancipatory and utopian fragments. The once political landscapes now become only sites of gaze, aesthetisation of nature.

In the second part of the film, we come to the real desert of the postsocialist transition. This time we find the landscape empty once more; there are practically no people, which strongly echoes Pavle Levi, who argues: 'What is missing are, of course, the people (Deleuze) ... People – yes, but... not only the living. The dead, too, are missing! There is a manifest absence of human bodies, all human bodies, in these films. Bodies engaged in various activities, behaviours, and ges-tures, whether mundane or extraordinary.'2 Nature seems to take some revenge on people, their wars, and horrific consequences, nature overgrows the railway tracks. The images and archival footage of new wars and genocide are absent. We might wonder whether the image of ethnic wars is absent because it bears no emancipatory and utopian fragments. The once political landscapes now become only sites of gaze, aesthetisation of nature.

2. The quote from Levi is taken from his article accessible online in the journal Senses of Cinema: https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2022/after-yugoslavia/the-cinema-of-cleansed-landscapes-on-image-politicsafter-yugoslavia/

Autor’s film transits from the cherished landscape of liberation and internationalist efforts into a sad picture of the scattered bodies of new wars. Can this railroad still evoke ways and traces apt to reactivate an internationalist spirit? The film gives us a clue, perhaps, as to how it can. It is not nature’s more obvious overgrowing of the railway tracks that overgrows the utopian past; rather, it is through the new movement along the tracks. Autor’s camera-eye focuses on the newcomers who use these tracks along the so-called Balkan route. The camera lingers on a group of female migrants/refugees from three different generations. The portraits of them make it clear that they are all from Palestine. Does the oldest of them, surely a survivor of the Nakba, know that one of her comrades was in Yugoslavia in 1947? Then we see women from the generation in between, all of whom know the Intifada well. Finally, the youngest generation remember their homes, even if they have been displaced or these homes are now destroyed; they are the ones who will be conveying these stories, and together continue liberation process.

Instead of recurring images of horror, perhaps one of the most decisive and inspiring material lays in multiplication of poems and expressions that oscillate between horror, hope and unfinished project of liberation in Palestine. Liberation of the (most) oppressed as new litmus test of humanity, which in new Cold War imaginary has to necessary rethink and organise along Tricontinental axes. Among many, I pick If I must die by Refaat Alareer to conclude this short journey:

Instead of recurring images of horror, perhaps one of the most decisive and inspiring material lays in multiplication of poems and expressions that oscillate between horror, hope and unfinished project of liberation in Palestine. Liberation of the (most) oppressed as new litmus test of humanity, which in new Cold War imaginary has to necessary rethink and organise along Tricontinental axes. Among many, I pick If I must die by Refaat Alareer to conclude this short journey:

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze—

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself—

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale.

Gal Kirn

Gal Kirn holds a PhD in Intercultural Studies of Ideas from the University of Nova Gorica (2012). He was a researcher at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht (2008-2010), and a research fellow at ICI Berlin (2010-2012). He also received a fellowship at the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart (2015), and was a postdoctoral fellow of the Humboldt-Foundation (2013-2016). He has been teaching courses in film, philosophy, and contemporary political theory at the Freie Universität Berlin and at Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen. He received an open topic position at TU Dresden (Slavic and Cultural studies) with an independent research project on ‘cinema-train’ (2017-2020). He is a guest researcher affiliated to the research project Social Contract in 21st Century at the Faculty of arts, University of Ljubljana.

Gal Kirn holds a PhD in Intercultural Studies of Ideas from the University of Nova Gorica (2012). He was a researcher at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht (2008-2010), and a research fellow at ICI Berlin (2010-2012). He also received a fellowship at the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart (2015), and was a postdoctoral fellow of the Humboldt-Foundation (2013-2016). He has been teaching courses in film, philosophy, and contemporary political theory at the Freie Universität Berlin and at Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen. He received an open topic position at TU Dresden (Slavic and Cultural studies) with an independent research project on ‘cinema-train’ (2017-2020). He is a guest researcher affiliated to the research project Social Contract in 21st Century at the Faculty of arts, University of Ljubljana.